Architecture in early modern Scotland facts for kids

Imagine Scotland's buildings from the early 1500s to the mid-1700s! This period, called "early modern," saw huge changes in how people lived and built. It started with the Renaissance (a time of new ideas in art and science) and the Protestant Reformation (changes in religion). It ended as the European Enlightenment (a time of new thinking) and the Industrial Revolution began.

Most people lived in small villages or isolated homes. They used local materials like stone, turf, and wood. The most common type of home was the "long house," where people and their animals lived under one roof! About 10% of Scots lived in towns called "burghs." Their homes were a mix of wood-framed and stone buildings.

The Renaissance brought new styles to Scottish architecture, especially for royal palaces like Linlithgow Palace. Then, the Reformation changed churches, making them simpler and less decorated. From the 1560s, rich families built unique "Scottish Baronial" homes. These combined fancy Renaissance ideas with features from old Scottish castles, making them grander and more comfortable.

After 1660, a new style called Palladian architecture became popular for large houses. Famous architects like Sir William Bruce and James Smith led this trend. After Scotland joined with England in 1707, military forts like Fort George were built to protect against rebellions. Scotland also produced amazing architects like Colen Campbell, James Gibbs, and William Adam. They greatly influenced Georgian architecture across Britain, including churches that looked like ancient Roman temples.

Contents

Homes for Everyone

Homes in Scotland used local materials and building methods. Poor families often built their own simple houses with help from friends and family. Stone was very common, used with or without mortar. If wood was available, curved timbers called "crucks" supported the roof. Sometimes, these crucks were raised on the walls.

Walls were often stone, with gaps filled with turf or plastered with clay. Some areas used woven branches (wattle) filled with turf, often on a stone base. Turf walls didn't last long and needed rebuilding every few years. In other places, like around Dundee, solid clay walls were used. Roofs were made of turf or thatch from broom, heather, straw, or reeds.

Most people lived in small villages or isolated homes. As the population grew, new villages appeared. Even summer huts for grazing animals, called shielings, sometimes became permanent homes. The typical house was a "long house" or "byre-dwelling." People and their animals lived under one roof, often separated by just a wall.

People noticed that homes in the Highlands and Islands were simpler. They often had one room, small windows, and dirt floors, shared by large families. In contrast, many Lowland cottages had separate rooms, plaster or paint on the outside, and even glass windows.

About 10% of Scots lived in "burghs" (towns). These towns often had a long main street with tall buildings. Narrow lanes and alleys, called "vennels" or "wynds," led off the main street. Many of these still exist today. In towns, traditional wooden, thatched houses mixed with larger stone homes. These belonged to merchants and richer families.

Most wooden houses are gone, but stone ones survive. For example, in Edinburgh, you can see Lady Stair's House and Gladstone's Land. Gladstone's Land is six stories tall! It shows how towns grew crowded, leading to taller buildings divided into tenements (apartments).

Many towns built "tollbooths" during this time. These buildings served as town halls, courts, and even prisons. They often had bells or clock towers and looked like small fortresses. The Old Tolbooth, Edinburgh was rebuilt in 1561 and housed the Scottish parliament. Other examples are in Tain, Culross, and Stonehaven. They often show influences from the Netherlands, with their distinctive "crow-stepped gables" and steeples.

Grand Palaces and Castles

Royal palaces were built and rebuilt a lot, starting with James III (1460–88). This work sped up under James IV (1488–1513) and reached its peak with James V (1513–42). These buildings show the influence of Renaissance architecture.

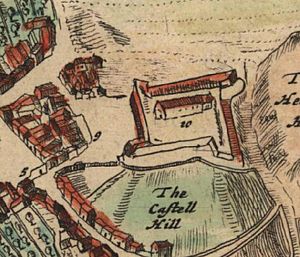

Linlithgow Palace was first built by James I (1406–27). It was called a "palace" from 1429, which was new for Scotland. James III expanded it, making it look like an Italian palace with four towers. It combined classic balance with knightly designs. Italian builders might have worked for James IV, who finished Linlithgow and rebuilt other palaces with Italian proportions.

In 1536, James V visited France and saw French Renaissance architecture. His second marriage to Mary of Guise two years later brought more French ideas. Buildings from his reign looked more European than English. Scottish architects didn't just copy. They mixed European styles with traditional Scottish designs and materials, especially stone. Some fancy wood carvings were even made by French craftsmen who moved to Scotland.

After Linlithgow, palaces like Holyrood Palace, Falkland Palace, Stirling Castle, and Edinburgh Castle were rebuilt. Historians call them "some of the finest examples of Renaissance architecture in Britain."

Many of these building projects were planned and paid for by James Hamilton of Finnart, who was in charge of royal works for James V. He also worked on Blackness Castle, Rothesay Castle, and other important buildings. Later, Mary of Guise hired an Italian military architect, Lorenzo Pomarelli. Even under James VI, Renaissance influences continued. For example, the Chapel Royal at Stirling had a classical entrance built in 1594. The North Wing of Linlithgow, built in 1618, used classical pediments (triangular roof sections). Rich families also built similar homes, like Mar's Wark in Stirling (around 1570) and Crichton Castle (1580s).

Simple Churches

Around 1560, the Protestant Reformation completely changed church building in Scotland. Protestants didn't like fancy decorations in churches. They believed there was no need for elaborate buildings with many separate areas for rituals. This led to many old church furnishings and decorations being destroyed.

New churches were built, and old ones were changed for Protestant services. The most important change was moving the pulpit (where the preacher stands) to the center of the church. This was because preaching was key to their worship. Many early churches were simple rectangular buildings with a pointed roof. This style continued into the 1600s, seen at Dunnottar Castle (1580s), Greenock (1591), and Durness (1619). These churches often had windows only on the south wall, which became a common feature.

Builders still used traditional materials. Some churches, like Kemback in Fife (1582), used rough stone for walls. Others used finely cut stone. A few added wooden steeples, like at Burntisland (1592). Greyfriars Kirk in Edinburgh, built between 1602 and 1620, was rectangular and mostly Gothic in style. But Dirleton (1612) had a more refined classical look.

A common church design after the Reformation was the "T"-shaped plan. This was often used when changing old churches. It allowed the most people to be close to the pulpit. You can see examples at Kemback and Prestonpans after 1595. This "T"-plan was used throughout the 1600s, for example, at Weem (1600) and New Cumnock (1657). In the 1600s, some churches, like Cawdor (1619), used a "Greek cross" plan (equal arms). But often, one arm was closed off for a rich family's private area, making them effectively "T"-plan churches.

Scottish Baronial Style

A special style of grand private houses in Scotland, later called "Scots Baronial," began in the 1560s. French builders who worked on royal palaces might have influenced it. This style kept many features of old Medieval castles, even though gunpowder weapons made high walls less useful. It also drew on the tower houses and peel towers that local lords had built for centuries, especially near the borders.

These new houses didn't have the strong outer walls of castles. They were more like fortified homes designed to survive a quick attack, not a long siege. They usually had three stories. They were often topped with a parapet (a low wall) that stuck out on corbels (stone supports). This parapet often continued into round towers called "bartizans" at each corner.

The new houses built from the late 1500s by nobles and lairds (landowners) were mainly for comfort, not defense. They kept many of the outside features that showed nobility. But they had a larger layout, often a "Z-plan." This meant a rectangular main building with towers at opposite corners, like Colliston Castle (1583) and Claypotts Castle (1569–88).

William Wallace, the king's master builder from 1617 until 1631, was very important. He worked on rebuilding the North Range of Linlithgow Palace from 1618. He also worked on Winton House, Moray House, and started Heriot's Hospital in Edinburgh.

Wallace created a unique style. He mixed Scottish castle features and Flemish (from Belgium/Netherlands) influences with a Renaissance layout. This was similar to the Château d'Ancy-le-Franc in France. You can see this style in noble homes like Caerlaverock (1620), Moray House (1628), and Drumlanrig Castle (1675–89). This style was very popular until the late 1600s, when grander English styles became fashionable.

New Styles and Forts

During the Civil Wars and when Scotland was part of the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland, most building was for military purposes. New forts were built to house English soldiers. These forts had many sides and triangular sections, designed to protect against cannon fire. Large forts were built at Ayr, Perth, and Leith. Twenty smaller forts were built across Scotland, from Orkney to Stornoway. New strongholds at Inverlocky and Inverness helped control the Highlands.

Universities also got more money during this time. They received income from church lands, which helped them finish buildings like the college in High Street in Glasgow. After the Restoration in 1660, when the king returned, large-scale building started again. People became very interested in Classicism (styles from ancient Greece and Rome).

Grand Country Houses

Sir William Bruce (around 1630–1710) is seen as the person who brought classical architecture to Scotland. He was key to introducing the Palladian style. Andrea Palladio (1508–80) was a very important architect from Venice in the 1500s. His buildings are known for their balance, good proportions, and classical elements. In England, Inigo Jones (1573–1652) introduced the Palladian style.

Bruce's style used Palladian ideas and was influenced by Jones. But it also borrowed from the Italian Baroque style and was strongly influenced by Sir Christopher Wren's (1632–1723) work in England. Bruce made a type of country house popular among Scottish nobles. These houses were designed more for enjoyment and less for defense, a trend already seen in Europe. He built and remodeled country houses like Thirlestane Castle and Prestonfield House.

One of his most important works was his own Palladian mansion, Kinross House, built on land he bought in 1675. Bruce's houses usually had finely cut stone on the outside. Rougher stone was only used for inside walls. As the king's main builder, Bruce rebuilt Holyrood Palace in the 1670s, giving it its current look. After Charles II died in 1685, Bruce lost favor and was even jailed for being suspected of supporting the Jacobites.

James Smith (around 1645–1731) worked as a builder on Bruce's Holyrood Palace project. In 1683, he became the person in charge of royal building works. With his father-in-law, master builder Robert Mylne (1633–1710), Smith worked on Caroline Park in Edinburgh (1685) and Drumlanrig Castle (1680s). Smith's country houses followed Bruce's style, with sloped roofs and classical fronts. They were simple but beautiful Palladian designs. Hamilton Palace (1695) had huge Corinthian columns and a grand entrance, but was otherwise plain. Dalkeith Palace (1702–10) was designed like William of Orange's palace in the Netherlands.

Churches with Classical Touches

By the late 1600s, both the Presbyterian and Episcopalian branches of the church used simple, modestly sized church designs that appeared after the Reformation. Most had a central plan with two or three sections, in a rectangular or T-shaped layout. Steeples remained important, either in the center or on one end, just like in older churches. Because of this, Scottish churches didn't have the fancy Baroque style seen in Europe and England.

Some small changes might show a move back towards the Episcopalian style during the Restoration. Lauder Church was built by Bruce in 1673 for the Duke of Lauderdale. Its Gothic windows might have hinted at old traditions, but its basic Greek cross plan fit within the common church designs.

The main exceptions were Smith's churches. He had been a Jesuit (a Catholic order) when he was young. His work included rebuilding Holyrood Abbey for James VII in 1687, which was very ornate. In 1691, Smith designed the tomb for Sir George Mackenzie of Rosehaugh in Greyfriars Kirkyard. It was a round building, like the Tempietto di San Pietro in Rome, designed by Donato Bramante (1444–1514).

A push for more Episcopalian worship might have led to more rectangular church plans, with the pulpit at the end opposite the entrance. The Latin Cross shape, popular in Catholic countries, was also used. An example is Smith's Kirk of the Canongate (1688–90). However, the Presbyterian revolution of 1689–90 happened before it was finished. The chancel (the part near the altar) was blocked off, turning it into a T-plan church.

Early 1700s Building Boom

After the Act of Union of 1707, Scotland became more prosperous. This led to a lot of new building, both public and private. Because of the threat of Jacobite rebellions, Scotland built more military structures than England during this time. These military buildings were designed to be very strong, with angled stone and earth to deflect cannon fire. This period of military building ended with the construction of Fort George near Inverness (1748–69). It has strong projecting bastions and redoubts (fortified outposts).

Influential Architects and Country Houses

Scotland produced some of the most important architects of the early 1700s. These included Colen Campbell (1676–1729), James Gibbs (1682–1754), and William Adam (1689–1748). All of them were influenced by Classical architecture. Campbell was influenced by the Palladian style and is credited with starting Georgian architecture. Some historians think he might have been a student of James Smith. Campbell spent most of his career in Italy and England. He became rivals with another Scot, James Gibbs, who also trained in Rome and worked mainly in England.

Campbell's style mixed Palladian elements with Italian Baroque forms and ideas from Inigo Jones. But he was most influenced by Sir Christopher Wren's interpretation of the Baroque. William Adam was the leading Scottish architect of his time. He designed and built many country houses and public buildings. Some of his most famous works are Hopetoun House near Edinburgh and Duff House in Banff. His unique, lively style was based on Palladian ideas, but with Baroque designs inspired by John Vanbrugh and European architecture. After he died, his sons Robert and John took over the family business. They became leading British architects in the second half of the century.

Classical Churches

In the 1700s, church building continued with familiar patterns. Many had T-shaped plans with steeples on the long side, like New Church, Dumfries (1724–27). William Adam's Hamilton Parish Church (1729–32) had a Greek cross plan inside a circle. John Douglas's Killin Church (1744) was octagonal (eight-sided).

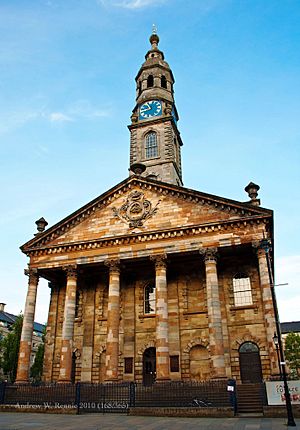

Scottish-born architect James Gibbs greatly influenced British church architecture. He brought a deliberately old-fashioned style to his rebuilding of St Martin-in-the-Fields, London. It had a huge, steepled portico (a porch with columns) and a rectangular plan with side aisles. Similar styles in Scotland can be seen at St Andrew's in the Square (1737–59). This was designed by Allan Dreghorn and built by Mungo Nasmyth. The smaller Donibristle Chapel (finished 1731) was designed by Alexander McGill. Gibbs' own design for St. Nicholas West, Aberdeen (1752–55), had the same rectangular plan with a main area and side aisles.

After the Toleration Act of 1712, Episcopalians began building a few new chapels. These included Alexander Jaffray's St Paul's chapel in Aberdeen (1721). There was also a meeting house designed by McGill in Montrose, an Edinburgh chapel opened in 1722, and St Andrew's-by-the-Green in Glasgow (1750–52). These adopted a simpler version of Gibbs' classical rectangular plan.

See Also

- Architecture of Scotland

- Architecture in Medieval Scotland

- Architecture in modern Scotland

- Domestic furnishing in early modern Scotland

|

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |