Michael Servetus facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Michael Servetus

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | Unknown, possibly 29 September 1511 |

| Died | 27 October 1553 (aged 42) |

| Alma mater | University of Paris |

| Occupation | Theologian, physician, editor, translator |

| Theological work | |

| Era | Renaissance |

| Tradition or movement | Renaissance humanism |

| Main interests | Theology, medicine |

| Notable ideas | Nontrinitarian Christology, pulmonary circulation |

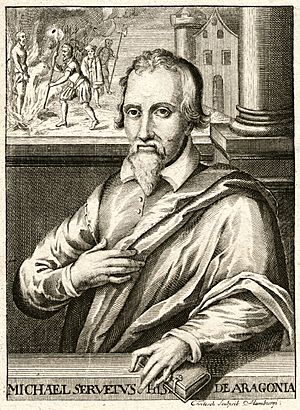

Michael Servetus (born around 1509 or 1511 – died October 27, 1553) was a very smart Spanish person. He was a theologian (someone who studies religion), a physician (doctor), a mapmaker, and a Renaissance humanist. This means he was interested in human achievements and learning.

Servetus was the first European to correctly explain how pulmonary circulation works. This is how blood travels from the heart to the lungs and back. He wrote about this in his book Christianismi Restitutio (1553). He was also a polymath, meaning he was good at many different subjects. These included mathematics, astronomy, geography, human anatomy, medicine, and studying the Bible.

He is famous in the history of medicine. He was part of the Protestant Reformation, a time when people wanted to change the Christian church. He later disagreed with the idea of the Trinity (God as three persons) and other common Christian beliefs. After being found guilty by Catholic leaders in France, he ran away to Calvinist Geneva. There, John Calvin himself spoke out against him. Servetus was then burned at the stake for heresy (having beliefs against official church teachings) by order of the city's leaders.

Who Was Michael Servetus?

Michael Servetus was a brilliant thinker from the Renaissance period. He made important discoveries in medicine and had strong ideas about religion. His life ended sadly because his beliefs were different from what was accepted at the time.

Early Life and Education

Michael Servetus was likely born in 1511 in Villanueva de Sigena, Spain. Some sources suggest he was born in 1509. His family's ancestors came from a small village called Serveto in the Aragonese Pyrenees mountains. His father was a notary, which is like a legal secretary.

Servetus had several brothers and sisters. His family used a nickname, "Revés," which was common in rural Spain. This nickname might have come from a family living in Villanueva who joined with the Servet family.

Where Did Servetus Study?

Servetus started his studies at a grammar school in Sariñena, Spain, until 1520. From 1520 to 1523, he studied Liberal Arts at the University of Zaragoza. This university was influenced by the ideas of Erasmus, a famous scholar. Servetus earned his Bachelor of Arts degree in 1523 and his Master of Arts degree the next year.

Around 1527, Servetus went to the University of Toulouse to study law. While there, he might have read religious books that were not allowed, possibly some Protestant writings.

Servetus's Career and Travels

In 1530, Servetus joined the group of Emperor Charles V. He worked as a page or secretary for the emperor's confessor (a religious advisor). Servetus traveled through Italy and Germany. He saw Charles V's coronation in Bologna. He was shocked by how fancy and rich the Pope and his group were. This made him want to follow the path of religious reform.

Servetus then visited Johannes Oecolampadius in Basel for about ten months. He probably worked as a proofreader for a printer there. By this time, he was already sharing his religious ideas. In 1531, he met other important reformers like Martin Bucer in Strasbourg.

His Early Books and New Name

In July 1531, Servetus published his first book, De Trinitatis Erroribus (On the Errors of the Trinity). The next year, he published Dialogorum de Trinitate (Dialogues on the Trinity). Because of problems with the Inquisition (a church court), Servetus started using the name "Michel de Villeneuve" while in France.

He also published the first French version of Ptolemy's Geography, a famous ancient map book. He dedicated this book and his edition of the Bible to his supporter, Hugues de la Porte. Servetus also wrote medical books, like Syruporum universia ratio (Complete Explanation of the Syrups), which made him well-known.

Studying Medicine in Paris

Servetus returned to Paris in 1536 to study medicine. His teachers included famous doctors like Jacobus Sylvius and Jean Fernel. He was considered a very skilled assistant in dissections (studying bodies). During this time, he wrote his Manuscript of the Complutense, which was a collection of his medical ideas.

He also taught mathematics and astrology. He even predicted when Mars would be hidden by the Moon. This made some of his medicine teachers jealous. His classes were stopped, and he faced problems with the university. Servetus then decided to go to Montpellier to finish his medical studies. He became a Doctor of Medicine in 1539.

Working in Vienne

After finishing his medical studies, Servetus became a doctor. He worked for Pierre Palmier, the Archbishop of Vienne, and for Guy de Maugiron, a local governor. Through a printer friend, Jean Frellon II, Servetus and John Calvin began writing letters to each other. Calvin used a fake name, "Charles d'Espeville." Servetus also became a French citizen, using his "De Villeneuve" name.

In 1553, Michael Servetus published another religious book called Christianismi Restitutio (The Restoration of Christianity). In this book, he strongly disagreed with the idea of predestination. This idea said that God decided who would go to Heaven or Hell, no matter what they did. Servetus believed that God only condemns those who condemn themselves through their actions.

This book also contained the first published description in Europe of how pulmonary circulation works. This was a major scientific discovery. Servetus had sent an early version of his book to Calvin. Calvin, who had written his own important book on Christian beliefs, saw Servetus's book as an attack on traditional Christian ideas. Calvin sent Servetus a copy of his own book, which Servetus sent back with many critical notes.

Calvin wrote to Servetus, "I neither hate you nor despise you; nor do I wish to persecute you; but I would be as hard as iron when I behold you insulting sound doctrine with so great audacity." Their letters became more heated, and Calvin eventually stopped writing to him. Calvin's frustration with Servetus grew. He even wrote to a friend in 1546: "If he comes here, if my authority is worth anything, I will never permit him to depart alive."

Imprisonment and Execution

On February 16, 1553, Michael Servetus was accused of being a heretic in Vienne, France. He was reported by Guillaume de Trie, a rich merchant who had moved to Geneva. On April 4, 1553, Servetus was arrested by Catholic leaders and put in prison in Vienne. He escaped three days later. On June 17, he was found guilty of heresy even though he was not there.

Servetus planned to escape to Italy. But for some reason, he stopped in Geneva, where Calvin and his followers had spoken out against him. On August 13, he went to hear Calvin give a sermon in Geneva. He was arrested after the service and put in prison again. All his property was taken away.

Servetus was put on trial. On October 24, he was sentenced to death by burning for denying the Trinity and infant baptism (baptizing babies). On October 27, Servetus was executed. He was burned on a pile of his own books at the Plateau of Champel in Geneva. Historians say his last words were: "Jesus, Son of the Eternal God, have mercy on me."

Servetus's Legacy

Servetus's death caused a lot of discussion. Many people, like Sebastian Castellio, spoke out against Calvin because of it. This event helped lead to the idea of religious tolerance in Europe.

Some other thinkers who did not believe in the Trinity became more careful about sharing their views. However, Servetus's writings were still shared widely after his death. His ideas influenced the start of the Unitarian movement in Poland and Transylvania. The Unitarian movement believes in one God, not a Trinity.

Servetus's Religious Ideas

In his first two books, Servetus rejected the common idea of the Trinity. He said it was not based on the Bible. He believed it came from Greek philosophers. He wanted to go back to the simpler teachings of the Gospels and early Christian leaders. Servetus hoped that removing the Trinity idea would make Christianity more appealing to followers of Judaism and Islam, who believe in one God. He thought that believing in the Trinity made Christianity seem like "tritheism," or believing in three gods.

Servetus believed that the divine Logos (God's Word or wisdom) became human in Jesus. This happened when God's spirit entered the Virgin Mary. He thought that Jesus became the Son only from the moment he was conceived. So, while the Logos was eternal, the Son himself was not eternal. Because of this, Servetus always called Christ "the Son of the eternal God," not the "eternal Son of God."

Andrew Dibb explained Servetus's view: "In 'Genesis' God reveals himself as the creator. In 'John' he reveals that he created by means of the Word, or Logos. Finally, also in 'John', he shows that this Logos became flesh and 'dwelt among us'. Creation took place by the spoken word, for God said 'Let there be ...' The spoken word of Genesis, the Logos of John, and the Christ, are all one and the same."

Servetus's ideas have been compared to other beliefs that Trinitarians rejected. However, Servetus himself rejected these comparisons in his books. He was accused of heresy because he kept denying the Trinity and the idea of three distinct divine Persons in one God.

Freedom of Conscience

Many people were upset by Servetus's death. This event is seen as a starting point for the idea of religious tolerance in Europe. This means people should be free to believe what they want. The Spanish scholar Ángel Alcalá said that Servetus's main legacies were his strong search for truth and the right to freedom of conscience.

The Polish-American scholar, Marian Hillar, studied how freedom of conscience developed. He said that Servetus died so that freedom of conscience could become a civil right in modern society.

Scientific Contributions

Servetus was the first European to describe how pulmonary circulation works. This is how blood moves from the heart to the lungs and back. His discovery was not widely known at the time for a few reasons. One reason was that he wrote about it in a religious book, Christianismi Restitutio, not a medical book. Also, most copies of his book were burned after it was published in 1553.

Only three copies of the book survived, and they were hidden for many years. In his book, Servetus explained that blood flows from the heart to the lungs. He figured this out by looking at the color of the blood, the size of the heart's chambers, and the large size of the pulmonary vein. This showed him that a lot of exchange was happening in the lungs. Servetus also wrote about the brain, nerves, eyes, and other parts of the body, showing his deep knowledge of anatomy. He also wrote about medical products in his other works.

Honors and Monuments

Geneva's Monuments

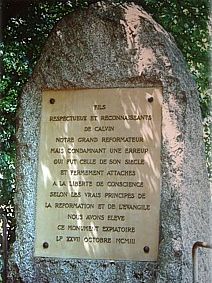

In Geneva, even 350 years after Servetus's execution, remembering him was still a touchy subject. In 1903, a group of Servetus's supporters wanted to build a monument for him. They asked a sculptor, Clotilde Roch, to create a statue showing Servetus suffering. The statue was finished in 1907. A nearby street was also named after him.

However, the city council did not want the statue to be put up. They said there was already a monument to Servetus. In 1942, the government took down the statue because it celebrated freedom of conscience. It was melted down. In 1960, the original molds were found, and the statue was remade and put back in its place.

Finally, on October 3, 2011, Geneva put up a copy of the statue it had rejected over 100 years before. It was made in Aragon from the original molds. The former mayor of Geneva, Rémy Pagani, opened the statue. He called Servetus "the dissident of dissidence." Leaders from the Catholic Church in Geneva and the Director of Geneva's International Museum of the Reformation attended the ceremony.

Honors in Aragon

In 1984, the public hospital in Zaragoza, Spain, changed its name to Miguel Servet. Since 1999, it has been known as the Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet. This was done to honor Servetus and his connection to the University of Zaragoza.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Miguel Servet para niños

In Spanish: Miguel Servet para niños