Heinrich Bullinger facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Heinrich Bullinger

|

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

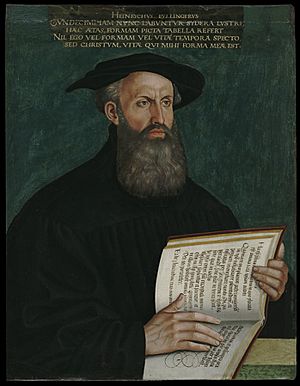

Portrait by Hans Asper, c. 1550

|

|||||||||||||

| Born | 18 July 1504 Bremgarten (Aargau), Canton of Aargau, Old Swiss Confederacy

|

||||||||||||

| Died | 17 September 1575 (aged 71) Zürich, Canton of Zürich, Old Swiss Confederacy

|

||||||||||||

| Nationality | Swiss | ||||||||||||

| Occupation | Theologian, antistes | ||||||||||||

| Spouse(s) | Anna Adlischwyler | ||||||||||||

| Parent(s) | Heinrich Bullinger and Anna Wiederkehr | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

Heinrich Bullinger (born July 18, 1504 – died September 17, 1575) was an important Swiss leader during the Reformation. He was a theologian, which means he studied religion. After Huldrych Zwingli died, Bullinger became the head of the Church of Zürich and a pastor at the Grossmünster church. He helped write important statements of faith called the Helvetic Confessions. He also worked with John Calvin to explain ideas about the Lord's Supper.

Contents

Heinrich Bullinger's Life and Work

Growing Up and Learning (1504–1522)

Heinrich Bullinger was born in Bremgarten (Aargau), Switzerland. His father, also named Heinrich Bullinger, was a priest, and his mother was Anna Wiederkehr. Heinrich was the youngest of seven children. His family was quite wealthy and often had guests. As a young child, Bullinger survived the plague and a serious accident.

At age 11, Bullinger went to a Latin school in Emmerich am Rhein. Even though his family was rich, his father made him beg for food for three years. This was to teach him to understand and care for poor people. At school, Bullinger studied classic books by writers like Horace and Virgil. He was also influenced by a group called the Brethren of the Common Life. They taught that living a good Christian life and reading the Bible were very important. Because of this, he thought about becoming a monk.

In 1519, at 14, he went to the University of Cologne. He was supposed to study there to become a priest like his father. Around 1520, he learned about the ideas of the Reformation. He read books by Martin Luther, like The Babylonian Captivity of the Church. He also read works by other reformers, such as Philip Melanchthon. Bullinger began to believe that people are saved by God's grace, not by their own good actions. He became a Protestant. He was also influenced by thinkers like Erasmus and important early church leaders such as Augustine.

In 1522, Bullinger earned his Master of Arts degree. He stopped taking part in the Eucharist (a Christian ceremony) and decided not to become a monk. When he returned home, his family accepted his new religious views. He was asked to lead a monastery, but he found the monks there were not serious about their faith. So, he went back home and spent months reading history, church writings, and Reformation ideas.

Early Swiss Reformation (1523–1531)

Teaching at Kappel Abbey (1523–1528)

In 1523, Bullinger became a teacher at Kappel Abbey, a monastery. He agreed to teach only if he didn't have to become a monk or attend Mass (a Catholic service). At Kappel Abbey, Bullinger started a plan for everyone to read and study the Bible. He also tried to change the school's lessons to be more focused on humanism and Protestant ideas. He found that the monks barely understood Latin, so he preached to them in Swiss-German. By 1525, the abbey stopped holding Mass. The next year, all the monks gave up their vows and took part in their first Reformed Eucharist.

During this time, Bullinger heard Huldrych Zwingli and Leo Jud preach in Zürich. In 1523, he met them and became friends with Zwingli. Bullinger was present at an important religious discussion in Zürich in 1525. Zwingli and the Waldensians influenced Bullinger to have a more symbolic understanding of the Eucharist. In 1527, he spent five months in Zürich studying Greek and Hebrew. He often attended Zwingli's Bible study group there. Zürich leaders sent Bullinger to help Zwingli at another important discussion in Bern. There, he met other reformers like Martin Bucer. In 1528, Bullinger left Kappel Abbey and became a minister in the new Reformed church of Zürich.

Bullinger also wrote religious papers about the Eucharist, agreements with God (covenants), images in churches, and how the church and society should work together. He sent these papers to nearby cities to try and convince them to join the Reformed side. These writings were criticized by Roman Catholics. Bullinger's love for humanism was clear in his writings about early church leaders and his belief that studying arts helped understand the Bible.

Marriage and Family Life (1529)

In 1527, Bullinger met Anna Adlischweiler, who used to be a nun, in Zürich. He proposed marriage directly to her, which was unusual for the time. They got engaged four weeks later. Anna's mother didn't want them to marry because she wanted Anna to marry a richer man and stay with her. She tried to stop the marriage legally but failed. Anna stayed with her mother until her mother died two years later. Anna and Bullinger then married on August 17, 1529. They had five daughters and six sons. All but one of their sons became Protestant ministers. They also adopted other children.

Ministry in Hausen and Bremgarten (1528–1531)

In June 1528, Bullinger started preaching part-time in Hausen. In February 1529, Bullinger's father gave up Roman Catholicism. Most of his church members approved, but city officials were worried about protests from Roman Catholics. After some debate, those who supported the Reformation won. Bullinger was chosen to take his father's place as minister. Within a week of his first sermon, the images and altar were removed from the church. Bullinger's father also officially married his mother in a Reformed ceremony. In Bremgarten, Bullinger preached four times a week and held a popular Bible study every day.

Leading the Church in Zürich (1531–1575)

Becoming Zwingli's Successor (1531)

Zwingli believed that war could help spread the Reformation, but Bullinger disagreed. When Zwingli called for war against the Catholic areas, Bullinger spoke against it. He believed that religious change should come only from preaching the gospel, not from fighting. After a short period of peace, Zwingli again sought military victory. This led to the Second War of Kappel. Roman Catholics attacked Bremgarten, where Bullinger was ministering. Zwingli was killed in the war. The peace agreement allowed each area to choose its own religion, but Bremgarten was forced to become Catholic again. Bullinger and his family lost almost everything and fled to Zürich.

As a leading Protestant preacher, Bullinger was immediately asked to be a pastor in other cities like Bern and Basel. Just three days after leaving Bremgarten, Bullinger preached at the Grossmünster church in Zürich. People said he preached so powerfully that it seemed like Zwingli had come back to life. On December 9, Zürich officially asked him to be Zwingli's successor as the head of the church, a position he held until his death in 1575. For the first ten years, Bullinger preached 12 sermons a week at the Grossmünster. He preached an estimated 28,000 sermons in total there.

Rebuilding the Zürich Church (1531–1532)

Bullinger's most important job was to rebuild the church in Zürich. He also continued to defend Zwingli's ideas. When the Zürich council first asked Bullinger to lead the church, they gave him seven conditions. One condition was that he should be peaceful and not get involved in government matters. Bullinger agreed that ministers should not hold government roles. However, he also said that ministers must be free to preach God's word, even if it differed from what the government wanted. Bullinger also had to defend the church against Roman Catholics who threatened to invade Zürich again. He convinced them that he supported the peace agreement and would not seek political conflict like Zwingli. In 1532, Bullinger helped create a peace agreement. It guaranteed freedom for Protestants and independence for Roman Catholics in Protestant areas.

In 1532, Bullinger and Leo Jud had a disagreement about church discipline. This turned into a debate about how the church and government should relate. Jud thought the church and government were separate, while Bullinger held a more traditional view. Jud wanted the church to handle its own discipline, separate from the government. Bullinger argued that this was only needed if the government was not Christian. A church meeting later sided with Bullinger. The church would be guided by both a civil council and the ministers. Each group had its own leader. For civil matters, the council was in charge, but ministers could disagree with and criticize the council.

Through this agreement, Bullinger set up his own church order. This became a model for other Reformed churches in German-speaking areas. Bullinger made the Zürich church more independent from government control. He personally oversaw other clergy and made sure that church and political disagreements were discussed privately. He kept himself informed about the 120 churches under his care. This allowed him to guide their appointments and ordinations of ministers.

Other Important Roles

Besides leading the church, Bullinger also served as Schulherr, or school principal. He was in charge of organizing Latin schools and religious education in Zürich. He changed Zwingli's Prophezei into the Lectorium, or Carolinum. This school provided higher education in theology. Although he helped run the Carolinum, he never taught there himself. He left the teaching to famous scholars like Peter Martyr Vermigli and his son-in-law Rudolf Gwalther.

Working with Anabaptists (1531–1560)

Bullinger wrote against the Anabaptists in his 1531 book. He saw Anabaptists as people who caused chaos and superstition. However, he allowed them to follow their beliefs and did not stop them from worshipping freely in Zürich. Bullinger kept this policy of allowing some freedom of worship for the rest of his life. During Bullinger's time leading Zürich (1531-1575), no Anabaptist was executed for their faith. In comparison, four Anabaptists were executed under Zwingli, and forty in Bern. However, after the Anabaptist Münster rebellion failed in 1534, Bullinger wrote a defense of the death penalty for Anabaptists who had disturbed public peace. Bullinger later wrote a long history of the Anabaptists called On the Origins of Anabaptism (1560). This book described their beginnings and spread in Europe. It was widely shared and is still used in histories of Anabaptists today.

Working with Lutherans (1536–1545)

In 1536, Bullinger and other Protestant reformers, including Jud and Martin Bucer, wrote the First Helvetic Confession. This was an attempt to agree on Protestant beliefs. The confession combined Zwinglian and Lutheran ideas. Many Protestant churches adopted it. However, Bullinger did not fully trust Bucer, and by 1538, talks to unite the Swiss and Lutheran churches failed. In his later years, Luther criticized the Swiss Zwinglians. Bullinger responded in 1545 with his own True Confession.

Working with Geneva

By the 1540s, Bullinger became closer to John Calvin of Geneva. They wrote a response to the Council of Trent together. Then, in 1549, they worked together to write the Consensus Tigurinus. This was an agreement between Calvinists and Zwinglians about the meaning of the Eucharist.

In the early 1550s, Bullinger published his most important work, Decades. This was a series of fifty sermons, written in Latin and published from 1548 to 1551. It was like a complete guide to his religious ideas. The sermons were widely shared, and Bullinger became even more famous as a Reformer. However, Zürich faced bad weather, poor harvests, political problems, and the plague. Bullinger's wife and daughter both died from the plague in the early 1560s.

Bullinger played a key role in writing the Second Helvetic Confession of 1566. He had written the first draft in 1562 as his own statement of faith. In 1564, he planned for it to be given to the Zürich Rathaus after his death. In 1566, after Frederick III, a German ruler, introduced Reformed ideas into churches in his area, Bullinger shared this statement of faith with Protestant cities in Switzerland. Many Swiss cities, including Bern, Zürich, and Geneva, liked it. This statement was also adopted by Reformed churches in Scotland, Hungary, France, and Poland. Only the Heidelberg Catechism was more famous as a Reformed statement of faith. The Second Helvetic Confession was also slightly changed to become other important confessions in France, Scotland, and Belgium.

Death

Bullinger died in Zürich in 1575. Zwingli's adopted son, Rudolf Gwalther, took over as the head of the church after him.

Heinrich Bullinger's Religious Ideas

The Eucharist

Bullinger's ideas about the Eucharist changed from Zwingli's. At first, Bullinger thought both the Old Testament Passover meal and the New Testament Lord's Supper were symbolic. This idea was in the First Helvetic Confession (1536). But in 1544, Bullinger argued that Christ's real spiritual presence happened in the Eucharist. He then combined the symbolic and spiritual presence ideas in the Consensus Tigurinus of 1549, which he wrote with Calvin. This idea was later included in the Heidelberg Catechism (1563) and the Second Helvetic Confession (1562/4).

Covenant Theology

Bullinger was very important in developing covenant theology in the Reformed tradition. This idea is about God making agreements or "covenants" with people. Bullinger first used covenants to understand the Eucharist. But by the 1550s, he used the idea of covenant as a main part of his theology.

Baptism

Like Zwingli, Bullinger strongly supported infant baptism, which is the baptism of babies.

Heinrich Bullinger's Writings

Bullinger wrote more than Luther and Calvin combined. Over 12,000 of his letters still exist. During his lifetime, his writings were translated into many languages and were among the most famous religious works in Europe.

Religious Works

Helvetic Confessions

Bullinger helped write the First Helvetic Confession. This was an early agreement document of the Reformation and showed Swiss religious ideas.

Bullinger also helped write the Second Helvetic Confession of 1566. He first wrote it himself in 1562 as his own statement of faith.

The Decades

Bullinger's main religious work was the Dekaden, or The Decades. It is a collection of 50 sermons that Bullinger published from 1549 to 1551. Many people think The Decades is as important as Calvin's Institutes of the Christian Religion for understanding early Reformed theology. Even though it was written like sermons, Bullinger probably never actually preached them. They are organized around the Ten Commandments, the Apostles' Creed, the Lord's Prayer, and the two Protestant sacraments. The book was quickly translated from Latin into German, French, Dutch, and English. It was one of the most popular Protestant religious books in the 1500s and 1600s. In some places, like the Netherlands, it was even required by law to have a copy on all Dutch trading ships. This helped it spread to America and Asia.

Other Religious Works

In 1531, Bullinger helped edit and write the introduction to the Zürich Bible with other scholars. Many of his sermons were translated into English. His works, which were mostly explanations of the Bible and arguments against other ideas, have not been collected into one big set.

Historical Writings

Besides religious works, Bullinger also wrote some valuable historical books. His main historical work, the "Tiguriner Chronik," is a history of Zürich from Roman times to the Reformation. He also wrote a history of the Reformation and a history of the Swiss confederation. Bullinger also wrote in detail about Biblical chronology. He believed the Bible provided a true and reliable timeline for all ancient history.

Letters

There are about 12,000 letters from and to Bullinger. This is the largest collection of letters from the Reformation period. A historian called him "a one-man communication system."

Bullinger was a personal friend and advisor to many important people of the Reformation era. He wrote letters to Reformed, Anglican, Lutheran, and Baptist theologians. He also corresponded with kings and queens like Henry VIII of England, Edward VI of England, Lady Jane Grey, and Elizabeth I of England.

Heinrich Bullinger's Lasting Impact

Bullinger's Helvetic Confessions are still used by Reformed churches as a guide for their beliefs. His work as a writer and historian is still important today. His ideas about covenant theology helped shape its development.

One of Bullinger's direct descendants was the British theologian E.W. Bullinger.

Impact on England

Bullinger welcomed Protestant refugees who were fleeing religious persecution in other countries to Zürich. After certain laws were passed in England in 1539 by Henry VIII of England, and again during the rule of Mary I of England from 1553 to 1558, Bullinger accepted many English refugees. When these English refugees returned to England after Mary I's death, Bullinger's writings became very popular there. In England, from 1550 to 1560, there were 77 editions of Bullinger's Latin Decades and 137 editions of their English translation, House Book. This book was about how to be a good pastor. In comparison, Calvin's Institutes had only two editions in England during the same time. By 1586, John Whitgrift, the Archbishop of Canterbury, ordered all new ministers who hadn't graduated from university to buy and read Bullinger's Decades. Because of his involvement and letters with English reformers, some historians believe Bullinger was one of the most influential theologians of the English Reformation.

Two of the English refugees were John and Anne Hooper. Anne later wrote letters to Bullinger. In 1546, Bullinger became the godfather of Hooper's daughter during her infant baptism. Bullinger also welcomed refugees from northern Italy and France, especially after the terrible St. Bartholomew's Day massacre. Johann Pestalozzi, a famous educator, was a descendant of these Italian refugees.

|

See also

In Spanish: Enrique Bullinger para niños

In Spanish: Enrique Bullinger para niños

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |