Battle of Bailén facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Bailén |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Peninsular War | |||||||

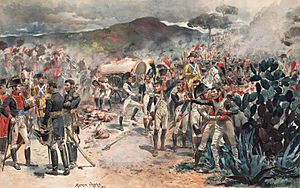

The Surrender of Bailén, by José Casado del Alisal (Museo del Prado) |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 20,000–24,430 | 29,770–30,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

1,000 dead or wounded | ||||||

The Battle of Bailén was a major fight in 1808 during the Peninsular War. It was fought between the Spanish Army of Andalusia, led by General General Castaños, and the French army under General General Dupont. This battle was very important because it was the first time a French army under Napoleon was defeated in an open battle. The main fighting happened near Bailén, a village by the Guadalquivir river in southern Spain.

In June 1808, people across Spain rose up against the French army that had taken over their country. Napoleon sent French military groups, called "flying columns," to calm down these uprisings. One of these groups, led by General Dupont, was sent south through Andalusia towards the port of Cádiz. Napoleon thought Dupont's 20,000 soldiers, even though many were new recruits, would easily defeat any resistance.

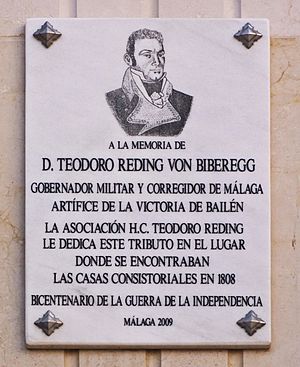

However, things did not go as planned. Dupont's men attacked and robbed Córdoba in July. General Castaños, leading the Spanish army, and General Theodor von Reding, the Governor of Málaga, met in Seville to plan how to fight the French. When Dupont learned that a larger Spanish force was coming, he moved back north. His soldiers were sick and had many wagons full of stolen goods. Dupont decided to wait for more soldiers from Madrid. But his messengers were caught and killed. Another French group, sent by Dupont to clear the road to Madrid, got separated from his main army.

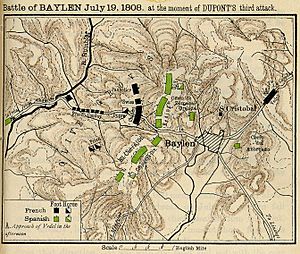

Between July 16 and 19, Spanish forces surrounded the French soldiers, who were spread out in villages along the Guadalquivir river. The Spanish attacked from several directions, confusing the French. General Castaños kept Dupont busy at Andújar. Meanwhile, General Reding crossed the river at Mengibar and took control of Bailén. This placed Reding's forces between Dupont's army and the other French group. Caught between Castaños and Reding, Dupont tried three times to break through the Spanish lines at Bailén. These attacks were bloody and desperate, and he lost 2,000 soldiers, and was even wounded himself. With his men running out of supplies and water in the hot weather, Dupont began talking with the Spanish about surrendering.

General Vedel, leading the other French group, finally arrived, but it was too late. Dupont had already agreed to surrender his own army and Vedel's army too, even though Vedel's soldiers were not yet surrounded and could have escaped. In total, 17,000 French soldiers were captured. This made Bailén the worst defeat for the French in the entire Peninsular War. The surrender terms said the French soldiers would be sent back to France. But the Spanish did not keep their promise. Instead, they sent the prisoners to the island of Cabrera, where most of them died from hunger.

When news of this huge defeat reached Joseph Bonaparte (Napoleon's brother, who was made King of Spain) in Madrid, the French army quickly retreated to the Ebro river. They left much of Spain to the Spanish fighters. People across Europe celebrated this first major defeat of Napoleon's army, which had seemed unbeatable. This victory inspired countries like Austria and showed that a whole country could fight back against Napoleon. This led to the formation of the Fifth Coalition against France.

Worried by these events, Napoleon decided to take charge of the war in Spain himself. He invaded Spain with his main army, the Grande Armée. They defeated the Spanish forces and their British allies, taking back lost areas, including Madrid, by November 1808. The fight in Spain continued for many years. The French spent huge amounts of money and soldiers fighting a long war against determined Spanish guerrilla fighters. Eventually, the French army was forced out of Spain, and southern France was invaded in 1814 by Spanish, British, and Portuguese forces.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened

The war in Spain had started with the Battles of El Bruch.

Months before, thousands of French troops had entered Spain. They were supposed to help Spain invade Portugal. But Napoleon used this chance to cause trouble within the Spanish royal family. A coup d'état (a sudden takeover of power) forced King Charles IV to give up his throne to his son Ferdinand. In April, Napoleon took both royals to Bayonne. He made them give up their claims to the throne and replaced the Spanish royal family with his own family, the Bonapartes. His brother Joseph Bonaparte was to become king.

However, the Spanish people did not like these changes. They stayed loyal to the old King Ferdinand and rebelled against having a foreign ruler. The people of Madrid rose up on May 2, killing 150 French soldiers. French troops quickly stopped this uprising with great force. Joseph Bonaparte was declared King of Spain in Madrid, but the people were angry. Spanish soldiers left the city and joined the rebels. Only the French army kept order in Madrid.

Outside the capital, the French army was in trouble. Most of the French army, about 80,000 soldiers, could only hold a small area in central Spain. This area stretched from Pamplona in the north to Madrid and Toledo in the south. The French commander, Marshal Joachim Murat, became sick and returned to France. General Anne Jean Marie René Savary took command of the French forces in Madrid.

With much of Spain openly rebelling, Napoleon set up his headquarters at Bayonne. He wanted to reorganize his troubled forces. Napoleon did not think much of his Spanish opponents. He believed a quick show of force would scare the rebels and help him control Spain. So, Napoleon sent several "flying columns" to stop the rebellion by taking over major Spanish cities.

- Marshal Jean-Baptiste Bessières went northwest from Madrid with 25,000 men.

- Marshal Bon Adrien Jeannot de Moncey marched towards Valencia with 29,350 men.

- General Guillaume Philibert Duhesme led 12,710 troops in Catalonia.

- General Pierre Dupont de l'Étang was to lead 13,000 men south towards Seville and the port of Cádiz. Cádiz was important because a French navy fleet was there.

War Reaches Andalusia

Dupont's army was mostly made up of less experienced soldiers. These troops were originally meant for police work or guarding areas in Prussia. This shows that Napoleon thought the Spanish campaign would be an easy "walk in the park." This force reached Córdoba in early June. In their first big battle in Andalusia, they captured the bridge at Alcolea. They easily defeated the Spanish troops trying to stop them. The French entered Córdoba that same afternoon and robbed the town for four days. However, as more and more people in Andalusia rose up, Dupont decided to pull back to the Sierra Morena mountains. He hoped for help from Madrid.

The French retreated in the very hot weather. They were slowed down by about 500 wagons full of stolen goods and 1,200 sick soldiers. A French doctor said, "Our small army carried enough baggage for 150,000 men." He added that "We owed our defeat to the greed of our generals." General Jacques-Nicolas Gobert's group left Madrid on July 2 to help Dupont. But only one part of his group reached Dupont. The rest were needed to hold the road north against the Spanish rebels.

Help Arrives in the Mountains

Napoleon and his military planners were worried about their communication lines and a possible British attack. So, they first focused on northern Spain. In mid-June, General Antoine Charles Louis Lasalle won a victory at Battle of Cabezón. This made things easier. With the Spanish fighters around Valladolid defeated, General Savary looked south. He decided to open up communication with Dupont in Andalusia. Napoleon was very keen to secure the southern provinces, where he expected the people to resist his brother Joseph's rule. On June 19, General Vedel, with Dupont's second infantry division, was sent south from Toledo. His job was to cross the Sierra Morena mountains, protect them from rebels, and meet up with Dupont.

Vedel started with 6,000 men, 700 horses, and 12 cannons. Along the way, smaller groups joined him. His column moved quickly across the plains without meeting resistance. However, any soldiers who fell behind were caught and killed by local people. On June 26, they reached the mountains. They found a group of Spanish soldiers and rebels blocking a pass. Vedel's troops attacked the ridge and captured the enemy cannons. They lost 17 men. Then they pushed south towards La Carolina. The next day, they met some of Dupont's troops who were preparing to attack the same passes from the south. With this meeting, communication between Dupont and Madrid was restored after a month of silence.

Confusing Orders

Vedel brought new orders from Madrid: Dupont was told to stop his march on Cádiz and move back northeast into the mountains. He was to watch the Spanish movements while waiting for more soldiers. These reinforcements were supposed to come after the cities of Zaragoza and Valencia surrendered. But these cities never surrendered. Marshal Moncey, who was supposed to take Valencia, was defeated there. About 17,000 Spanish soldiers gathered around Valencia. Moncey gave up, having lost 1,000 men trying to attack the city walls. This meant Moncey's army could not help Dupont. No troops came from Aragon either, as Zaragoza fought off French attacks. Meanwhile, General Savary prepared for Joseph Bonaparte to arrive in Madrid. Many French groups were pulled back to protect Madrid. Dupont was told to stay close to help Madrid if the fighting in the north went badly.

However, Dupont's mission to Andalusia was never completely cancelled. Savary kept sending vague orders, promising reinforcements later. Napoleon was angry at the idea of giving up even Andújar to the Spanish. With things unclear, Dupont decided to stay put along the Guadalquivir river. He robbed and occupied the town of Bailén and the city of Jaén. Napoleon wrote, "even if he suffers a setback, ... he will just have to come back over the Sierra."

Spain Gets Ready

When General Castaños learned that the French were entering the southern provinces, he guessed Dupont's plans. He prepared his army in a strong camp near Cádiz. But Dupont's retreat made these preparations unnecessary. Castaños set up his headquarters in Utrera. He organized the Army of Andalusia into four groups, or divisions. These were led by Generals Theodor von Reding, Antonio Malet, Marquis of Coupigny, Félix Jones, and a fourth (Reserve) under Manuel Lapeña. Lapeña's division included Colonel Juan de la Cruz Mourgeón's group of about 1,000 skirmishers (lightly armed soldiers) and armed peasants.

Stuck on the Guadalquivir

Dupont stayed at Andújar with two divisions, trying to control the main road between Madrid and Seville. Meanwhile, Castaños' four divisions steadily advanced from the south. Rebels from Granada marched to block the road to the mountains. Vedel's division was placed east at Bailén to guard these mountain passes. On July 1, Vedel had to send a group under General Louis Victorin Cassagne to stop the rebels advancing on Jaén and La Carolina. This stretched the French line even further east. Meanwhile, General Liger-Bélair, with 1,500 men, moved to a forward post at Mengíbar, a village on the south bank of the Guadalquivir. At Andújar, a tower by the river was made stronger, and small defenses were built. But the Guadalquivir river could be crossed in many places, and it was open to fire from the hills. Dupont's defenses were not very strong. Cassagne returned to Bailén on July 5 after driving off the rebels. He had lost 200 men and found no supplies in the towns.

Finally, some of the promised reinforcements arrived. Generals Gobert and Jacques Lefranc passed through the mountains on July 15. They left a strong guard in the mountains and came down into Andalusia with their remaining soldiers. Dupont now had over 20,000 men waiting along the Guadalquivir. But supplies were low. The Spanish peasants had left their fields, so Dupont's tired men had to harvest crops and prepare their own food. Six hundred men got sick during their two-week stay from drinking bad water from the Guadalquivir. French soldiers said, "The situation was terrible. Every night, we heard armed peasants roaming around us... and every night, we expected to be assassinated."

First Fights

On July 9, General Lapeña's division took up a position from El Carpio to Porcuna. The Spanish army began to make several moves against the French. From west to east along the Guadalquivir, Castaños with 14,000 men approached Dupont at Andújar. Coupigny moved his division to Villa Nueva. Reding prepared to cross the river at Mengíbar and move north to Bailén. This would go around the French and cut off Dupont's escape route to the mountains. Marching east to Jaén, Reding launched a strong attack against the French on July 2 and 3. The Spanish were forced back, but the French group felt in danger. On the 4th, Cassagne fell back across the Guadalquivir to Bailén, leaving only a few companies to guard the ferry at Mengíbar.

Reding attacked Mengíbar again on July 13 and drove Ligier-Belair out of the village after a tough fight. However, when Vedel's division appeared, the Spanish group quietly pulled back, and French soldiers took back the town. The next day, Coupigny tested the French positions at Villa Nueva and had a sharp fight with the French guards. Castaños reached the heights at Arjonilla on July 15. He set up cannons overlooking Andújar and began firing at Dupont. At the same time, 1,600 skirmishers and irregulars under Colonel Cruz-Mourgeón crossed the river near Marmolejo. They attacked towards Dupont's rear, but a French battalion easily pushed them back into the hills. Worried by this attack, Dupont asked Vedel to send help. Vedel, thinking Mengíbar was not seriously threatened, left with his entire division during the night. Vedel's arrival ended the threat at Andújar. But it left the French left side (Mengíbar—Bailén—La Carolina) in great danger, with Ligier-Belair having very few troops to fight Reding.

The Battle Begins

On July 16, Dupont and Vedel expected a tough fight at Andújar. But they found Castaños and Coupigny only making noise, not seriously trying to cross. Reding, however, was on the move. He made a fake attack towards the Mengibar ferry. Then his Swiss soldiers crossed the river upstream at Rincon. They surrounded Mengibar and crushed the French battalions under Ligier-Belair. General Gobert, rushing from Bailén to help, was shot in the head and later died. His counterattack failed. The French general, Dufour, pulled his men back to Bailén.

Dupont learned about the loss of Mengibar and hesitated again. He did not use Vedel's presence to attack Castaños. Instead, Dupont stayed at Andújar and ordered Vedel's tired division back to Bailén. This was to stop the right side of the French army from collapsing.

French Right Wing Moves Back

The fighting around Mengibar then took a strange turn. Reding, after finally crossing the river, suddenly retreated to the other side. He might have felt alone with his division. At the same time, rebels under Colonel Valdecanos appeared on Dufour's side. They scattered his guards and threatened the road to the mountains. Dufour, worried about the mountain passes, went to fight the Spanish rebels at Guarromán and La Carolina. So, when Vedel marched back to Bailén, he found the area strangely empty of both friends and enemies.

When his scouts found no enemy at the Guadalquivir, Vedel thought Reding had moved his division somewhere else. Dufour sent worrying reports from Guarromán. He convinced Vedel that 10,000 Spanish soldiers were marching on the mountains behind them. This was too much for Vedel. He gathered his exhausted division and rushed to Dufour's aid on July 17. He arrived at Santa Carolina the next day. Dufour's big mistake was soon clear. Vedel found that the small group of rebels was not a big threat. For the third time, the Spanish had tricked him. Reding was still somewhere around Mengibar, out of sight. Worse, there was now a huge gap between Dupont and Vedel. No French soldiers were left to stop Reding from taking the central position at Bailén.

Trapped in Battle

News of Vedel's bad moves reached Dupont at noon on July 18. This convinced him to fall back to Bailén and call Vedel back there too. He wanted to bring his scattered army back together. Dupont said, "I do not care to occupy Andujar. That post is of no consequence." He watched Castaños' groups across the river. Dupont needed time to prepare his wagons, which were full of stolen goods from Cordoba. So, he delayed his retreat until nightfall, hoping to hide his departure from the Spanish. Meanwhile, Reding, calling up Coupigny's division, had crossed at Mengibar on July 17. He took the empty Bailén, camped there for the night, and prepared to move west towards Dupont's position in the morning.

Vedel left La Carolina at 5:00 a.m. on July 18. He rushed the tired French right wing southwest towards Bailén. He did not know he was heading towards Reding's rear. Both armies were now north of the Guadalquivir. They were in a strange position: Dupont was between Castaños and Reding; Reding was between Dupont and Vedel. At Guarromán, Vedel rested his tired troops for a few hours. He could not refuse this after three days and nights of constant marching. Scouts went west to Linares to protect his rear. Reding did not know that Dupont was moving towards him, nor that Vedel was now behind him. Reding left a few battalions to hold Bailén and set off with his two divisions westward on July 18. He planned to surround Andújar from the rear and trap Dupont against Castaños.

Dupont slipped away from Andújar without being seen. At dawn on July 19, his lead group met Reding's first soldiers near Bailén. Reding was surprised but reacted quickly. He formed a defensive line with 20 cannons in an olive grove. Dupont's general, Chabert, badly underestimated the Spanish force. He charged his 3,000 men into Reding's two divisions. The Spanish fired from the sides and pushed them back with heavy losses. Dupont, following with the main part of his army, stopped the bloody advance. He ordered all other groups forward to try and break Reding's line.

Dupont expected Castaños' groups to catch up and crush him at any moment. One Spanish division was already pursuing him. Dupont sent his troops into battle in small groups, without keeping any soldiers in reserve. His troops were "exhausted and spread out," and sending them into battle like this was very foolish. Generals Chabert and Duprès led an attack against the Spanish left side. But they gained no ground, and Duprès was badly wounded. Dupont's cannons were slowly set up to support the attack, only to be destroyed by the stronger Spanish artillery. On the right, a fierce attack pushed back the Spanish line. The French cavalry rode over a Spanish infantry group and reached the cannons. But the Spanish kept firing and forced the French to leave the captured guns and fall back.

Fresh French troops arrived at 10:00 a.m. Dupont immediately launched a third attack. One last group joined them: d'Augier's marines of the Imperial Guard. These were supposed to be the best troops. Dupont, wounded in the hip, gathered his tired soldiers around the Guard battalion for a final try to break through to Bailén. At this point, fresh soldiers might have broken the Spanish line. But Dupont had none. The French groups, hit hard by Spanish cannons, were forced back for the third time. Dupont's Swiss regiments, who used to serve Spain, switched sides and joined their old masters. Finally, Castaños' force arrived. The day was lost.

The Surrender

An unexpected Spanish reinforcement appeared in the last minutes of the battle. Colonel de la Cruz, who had been driven into the mountains earlier, had gathered 2,000 sharpshooters. He came back down towards the battle, guided by the sound of firing. Dupont was now completely surrounded on three sides.

Around noon, as Dupont's cannons fell silent, Vedel continued from Guarromán to Bailén. He saw sleeping troops that he thought were Dupont's lead group returning. But they were actually Reding's Spanish soldiers. Vedel and Reding prepared for battle. Two Spanish officers approached Vedel under a flag of truce. They announced that Dupont had been badly defeated and wanted to stop fighting. Vedel replied, "Tell your General, that I care nothing about that, and that I am going to attack him."

Vedel directed his soldiers against the Spanish position. While his men fought, his cavalry rode around the enemy side, trampled some Spanish militia, and surrounded the hill. Their cannons lost, the Irish battalion surrendered, and Vedel's men took the hill and 1,500 prisoners. Meanwhile, another French group attacked a strong Spanish point. But the Spanish soldiers held their ground firmly, and all attacks failed.

When Castaños arrived, Dupont decided to ask for a truce. He negotiated terms with the Spanish officers for several days. After learning this, Vedel pulled back some distance. Spanish commanders threatened to harm the French soldiers if Vedel's group did not surrender. So, Dupont forced Vedel to return and lay down his weapons. Handing his sword to Castaños, Dupont said, "You may well, General, be proud of this day; it is remarkable because I have never lost a pitched battle until now—I who have been in more than twenty." Castaños replied sharply, "It is the more remarkable because I was never in one before in my life."

What Happened Next

The Spanish war continued with the Second siege of Girona.

The Impact of the Victory

News of the Spanish victory encouraged many Spanish leaders to join the rebellions happening across the country. Suddenly, it seemed possible to drive the French out of Spain by force. At the same time, the Spanish victory in this small village showed armies across Europe that the French, who had seemed unbeatable for a long time, could be defeated. This fact convinced the Austrian Empire to start the War of the Fifth Coalition against Napoleon.

This was a historic moment. News of it spread quickly throughout Spain and then all of Europe. It was the first time since 1801 that a large French force had surrendered. The idea that the French were unbeatable was severely shaken. Everywhere, people who were against France found new hope. The Pope spoke out against Napoleon. People in Prussia were encouraged. Most importantly, the Austrian leaders who wanted war began to get the support of Emperor Francis for a new challenge to the French Empire.

To celebrate this important victory, the Seville Junta (a governing council) created the Medalla de Bailén (Bailén Medal).

The defeat deeply angered Napoleon. He saw Dupont's surrender as a personal insult and a stain on his empire's honor. He punished everyone involved very harshly. Dupont and Vedel returned to Paris in disgrace. They were put on trial by a military court, stripped of their rank and titles, and imprisoned for their role in the disaster. Napoleon believed his army in Spain had been "commanded by postal inspectors rather than generals." In January 1809, Napoleon stopped a military parade when he saw Dupont's chief of staff. He scolded the officer in front of all the troops and ordered him off the square. According to General Foy, Napoleon began his angry speech by saying, "What, general! did not your hand wither up when you signed that infamous capitulation?" Years later, Napoleon started an official investigation into the surrender. An Imperial decree, dated May 1, 1812, banned any field commander from negotiating a surrender. It declared any unauthorized surrender a crime punishable by death.

French Retreat and Return

Besides hurting French prestige, Bailén caused panic and confusion among the French invasion forces. They were already struggling after failing to take Gerona, Zaragoza, Valencia, Barcelona, and Santander. The country was quickly arming against them. With the sudden loss of 20,000 soldiers, Napoleon's military machine fell apart. On General Savary's advice, Joseph Bonaparte fled from the openly hostile capital. Generals Bessières and Moncey joined him on the road. They pulled the French troops north from Madrid and continued past Burgos in a complete retreat. The French did not stop until they were safely across the Ebro river. There, they could set up strong defenses and wait. From his temporary headquarters, Joseph wrote to his brother sadly, "I repeat that we have not a single Spanish supporter. The whole nation is exasperated and determined to fight." Napoleon was furious and upset, saying that crossing the Ebro was "like giving up Spain."

In November, Napoleon led most of his Grande Armée across the Pyrenees mountains. He dealt a series of crushing blows to the Spanish forces. He recaptured Madrid in just about a month. Fate was especially cruel to the victors of Bailén. Castaños was defeated by Marshal Lannes at the Battle of Tudela in November 1808. Reding was run over by French cavalry at the Battle of Valls in 1809 and died from his wounds. Marshal Soult took over much of Andalusia the next year. On January 21, 1810, his men found the lost French Imperial Eagles (battle flags) from the cathedral of Bailén. Soon, only Cádiz remained firmly in Spanish hands. A difficult war lay ahead to drive the French out of Spain.

What Happened to the Prisoners

Dupont and his officers were taken on British navy ships to Rochefort harbor. This happened after the Seville Junta refused to honor the agreement that the French soldiers would be sent back to France through Cádiz. The French prisoners were kept in Cádiz harbor on prison hulks. These were old warships with their masts and rigging removed. They were fed irregularly on the overcrowded ships. When the Siege of Cádiz began in 1810, French troops occupied the land around the city. From March 6 to 9, 1810, a strong storm hit. It drove one Portuguese and three Spanish warships ashore, where French cannons destroyed them. Thirty merchant ships also sank or were driven ashore in the same storm. One ship had 300 British soldiers who became prisoners of war. The French officers, who were kept on the Castilla, noticed that ships that had lost their anchors had drifted to the opposite shore during the storm. During the next storm, on the night of March 15 and 16, the officers overpowered their Spanish guards and cut the prison ship's ropes. The French fought off two gunboats that tried to retake the ship. Over 600 escaped when the Castilla ran aground on the French side of the bay. Ten days later, the prisoners on another ship, the Argonauta, tried the same thing. But they had a worse fate. The ship got stuck in the harbor and was fired upon by several gunboats. Eventually, the ship caught fire, and fewer than half of the prisoners survived to be rescued by their friends.

The few remaining officers were first moved to Majorca and later to England. The regular soldiers were sent to the Canary and Balearic Islands. The people living there protested having so many enemies nearby. So, 7,000 prisoners were put on the uninhabited island of Cabrera. The Spanish government, which could barely supply its own armies, could not properly care for the prisoners. On July 6, 1814, the remaining survivors of Bailén returned to France. Fewer than half were left, as most had died in captivity. Many of the survivors never fully recovered their health after this experience.

Battle of Bailén in Books

- F. L. Lucas's novel The English Agent – A Tale of the Peninsular War (1969) is about the Battle of Bailén and what happened after. It tells the story of a British Army officer gathering information before the first British landings.

- Duke of Rivas wrote a poem about the battle called "Bailén."

See also

In Spanish: Batalla de Bailén para niños

In Spanish: Batalla de Bailén para niños

| Madam C. J. Walker |

| Janet Emerson Bashen |

| Annie Turnbo Malone |

| Maggie L. Walker |