Franco-Dutch War facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Franco-Dutch War |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the wars of Louis XIV | |||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 120,000 killed or wounded | 100,000 killed or wounded | ||||||||

| 342,000 total military deaths | |||||||||

The Franco-Dutch War, also known as the Dutch War, was a big conflict fought between France and the Dutch Republic. The Dutch were supported by their allies: the Holy Roman Empire, Spain, Brandenburg-Prussia, and Denmark–Norway. At the start, France had allies too, like the Bishopric of Münster, Cologne, and England. Two other wars, the Third Anglo-Dutch War (1672–1674) and the Scanian War (1675–1679), were part of this larger conflict.

The war began in May 1672. France almost completely took over the Dutch Republic. This year is still remembered in the Netherlands as the Rampjaar, meaning "Disaster Year". However, the Dutch stopped the French advance in June using their Dutch Water Line. This was a defense system of flooded lands. By late July, the Dutch position became stable. Other European countries worried about France's growing power. In August 1673, the Dutch, Emperor Leopold I, Spain, and Brandenburg-Prussia formed an alliance against France. Lorraine and Denmark also joined them. England made peace with the Dutch in February 1674.

Facing war on many fronts, the French army left the Dutch Republic. They only kept control of Grave and Maastricht. King Louis XIV of France then focused his efforts on the Spanish Netherlands and the Rhineland. The allied forces, led by William of Orange, tried to stop France from gaining more land. After 1674, France took over Franche-Comté and areas along its border with the Spanish Netherlands and in Alsace. But neither side could win a clear victory.

The war ended with the Peace of Nijmegen in September 1678. Even though the peace terms were not as good for France as they could have been earlier, this war is often seen as the peak of French military success under Louis XIV. It was a big win for his public image. Spain got Charleroi back from France. But Spain gave up Franche-Comté and large parts of Artois and Hainaut to France. These new borders mostly stayed the same for a long time. Under William of Orange's leadership, the Dutch got back all the land they lost in the terrible early stages of the war. This success made him a very important leader in Dutch politics. It helped him stand up to France's continued expansion and create a strong alliance, the Grand Alliance, which fought in the Nine Years' War later on.

Contents

Why the War Started: The Origins

France had a long history of opposing the Habsburg family's power in Europe. Because of this, France supported the Dutch Republic during their Eighty Years War (1568–1648) against Spain. The Peace of Münster in 1648 confirmed the Dutch Republic's independence. It also permanently closed the Scheldt river mouth. This helped Amsterdam by removing its rival port, Antwerp.

Keeping this trade advantage was very important to the Dutch. But this goal increasingly clashed with France's plans for the Spanish Netherlands. France wanted to reopen Antwerp's port.

When William II of Orange died in 1650, the Dutch Republic entered a period without a main leader, called the First Stadtholderless Period. Political power went to the rich city leaders, known as Regenten. This gave a lot of power to the States of Holland and Amsterdam. Johan de Witt was the most powerful official, the Grand Pensionary, from 1653 to 1672. He believed that a good relationship with Louis XIV of France was key to keeping Dutch economic power. It also protected him from his political rivals, the Orangists.

France and the Dutch Republic signed a treaty in 1662 to help each other. However, the States of Holland did not want to divide the Spanish Netherlands with France. This made Louis XIV believe he could only achieve his goals by force. The Dutch received little help from France during the Second Anglo-Dutch War (1665–1667). They increasingly preferred a weak Spain as a neighbor over a strong France. In May 1667, Louis started the War of Devolution. He quickly took over most of the Spanish Netherlands and Franche-Comté.

In July, the Treaty of Breda ended the Anglo-Dutch War. This led to talks between the Dutch and Charles II of England about working together against France. Spain and Emperor Leopold also supported this, as they were worried about France's expansion. Charles II first suggested an alliance with France, but Louis rejected it. So, Charles joined the Triple Alliance in 1668, with England, the Dutch Republic, and Sweden. This alliance helped France and Spain make peace. Louis gave up many of his gains in the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1668.

The treaties of Breda and Aix-la-Chapelle seemed like big diplomatic wins for the Dutch. But they also created serious dangers. De Witt knew this, but he couldn't convince his colleagues. Louis XIV saw a treaty he made with Leopold in January 1668 as proof of his right to the Spanish Netherlands. The Aix-la-Chapelle treaty, despite his giving up some land, reinforced this idea. He no longer felt the need to negotiate. He decided the best way to get the Spanish Netherlands was to defeat the Dutch Republic first.

The Dutch also thought they were stronger than they were. A defeat at Lowestoft in 1665 showed problems with their navy. The successful Raid on the Medway in 1667 happened mostly because England was short on money. In 1667, the Dutch States Navy was very strong. But England and France quickly built up their navies, reducing this advantage. The Anglo-Dutch War was mainly fought at sea. This hid the poor state of the Dutch army and forts. These had been neglected because they were seen as strengthening the power of the Prince of Orange.

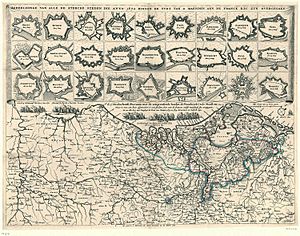

To prepare for an attack on the Dutch Republic, Louis XIV started several diplomatic efforts. First, he signed the Secret Treaty of Dover in 1670. This was a secret alliance between England and France against the Dutch. It included secret parts, not known until 1771. One part was that Charles II would get £230,000 a year for providing 6,000 British soldiers. Agreements with the Bishopric of Münster and Electorate of Cologne allowed French forces to bypass the Spanish Netherlands. They could attack through the Bishopric of Liège, which was part of Cologne (see Map). All preparations were finished by April 1672. At this time, Charles XI of Sweden agreed to French money in exchange for invading parts of Pomerania claimed by Brandenburg-Prussia.

Preparing for Battle

French armies at this time had big advantages. They had one clear command, skilled generals like Turenne, Condé, and Luxembourg. They also had much better ways to get supplies. Changes made by Louvois, the Secretary of War, helped them quickly get large armies ready. This meant the French could attack early in spring before their enemies were prepared. They could take their targets and then defend them. Like in other wars of this time, the army's size changed. It started with 180,000 men in 1672. By 1678, it was planned to have 219,250 foot soldiers and 60,360 cavalry. About 116,370 of these served in garrisons (forts).

Keeping border towns like Charleroi and Tournai in 1668 allowed Louvois to set up supply depots. These stretched from the French border to Neuss in the Rhineland. 120,000 men were assigned to attack the Dutch Republic. They were split into two main groups. One was at Charleroi, led by Turenne. The other was near Sedan, led by Condé. After marching through the Bishopric of Liège, they would meet near Maastricht. Then, they would take over the Duchy of Cleves, which belonged to Frederick William, Elector of Brandenburg. At the same time, 30,000 hired soldiers, paid by Münster and Cologne and led by Luxembourg, would attack from the east. A final plan was for English troops to land in the Spanish Netherlands. But this became impossible when the Dutch kept control of the sea at Solebay in June.

The French had shown their new tactics when they quickly took over the Duchy of Lorraine in mid-1670. The Dutch received accurate information about French plans as early as February 1671. Condé confirmed these plans in November and again in January 1672. Dutch leader de Groot called Condé "one of our best friends." However, the Dutch were not ready for a war against France. Most of their money had gone into the navy, not their land defenses. Most of the Dutch States Army was in three southern forts: Breda, 's-Hertogenbosch, and Maastricht. In November 1671, the Council of State reported these forts were low on supplies and money, and many defenses were barely usable. Most army units were much smaller than they should have been. On June 12, one officer reported his unit, officially eighteen companies strong, only had enough men for four.

This was partly because Prince William was now old enough to lead. His supporters, the Orangists, refused to approve more military spending unless he was made Captain-General. De Witt opposed this. The Dutch knew there was some opposition in England to the Anglo-French alliance. They relied on the Triple Alliance treaty, which said England and the Dutch Republic would support each other if attacked by Spain or France. The Parliament of England also believed this. They approved money for the fleet in early 1671 to meet their treaty duties. The real danger became clear on March 23. Following orders from Charles II, the Royal Navy attacked a Dutch merchant convoy in the Channel. A similar event had happened in 1664.

In February 1672, de Witt agreed to appoint William as Captain-General for one year. Budgets were approved to increase the army to over 80,000 men. But it would take months to gather these soldiers. Talks with Frederick William to send 30,000 men to strengthen Cleves were delayed. He demanded Dutch-held forts on the Rhine, like Rheinberg and Wesel. By the time they agreed on May 6, he was busy with a Swedish invasion of Pomerania, supported by France. So, he couldn't fight the French in 1672. The Maastricht garrison was increased to 11,000. The hope was they could delay the French long enough to strengthen the eastern border. Cities provided 12,000 men from their civil militia. 70,000 farmers were forced to build earthworks along the IJssel river. These were not finished when France declared war on April 6, followed by England on April 7. Münster and Cologne joined the war on May 18.

The French Attack in 1672

France Crosses the Rhine River

The French attack started on May 4, 1672. A smaller force led by Condé left Sedan and marched north along the Meuse river. The next day, Louis XIV arrived in Charleroi to inspect the main army of 50,000 men, led by Turenne. This was one of the most impressive displays of military power in the 1600s. On May 17, Louis and Turenne met Condé at Visé, south of Maastricht. Louis wanted to attack Maastricht right away, but Turenne convinced him it was a bad idea. It would give the Dutch time to strengthen other places. Turenne avoided a direct attack on Maastricht. Instead, he took over nearby areas like Tongeren, Maaseik, and Valkenburg to stop the city from getting help.

Leaving 10,000 men to watch Maastricht, the rest of the French army crossed back over the Meuse. They then moved along the Rhine river. Troops from Münster and the Electorate of Cologne, led by Luxembourg, supported them. The Dutch forts meant to defend the Rhine crossings were still very short on men and equipment. By June 5, the French had captured Rheinberg, Orsoy, and Burick with very little fighting. Wesel, a very important fort, surrendered when the townspeople threatened to kill their commanders. Rees fell on June 9. With their rear secured, most of the French army began to cross the Rhine at Emmerich am Rhein. Grand Pensionary De Witt was deeply shocked by this disaster. He said, "the fatherland is now lost."

Even though the situation on land was terrible for the Dutch, things were much better at sea. On June 7, Dutch Lieutenant-Admiral Michiel de Ruyter attacked the Anglo-French fleet. It was taking on supplies at Southwold on the English coast. The French ships, led by d'Estrées, did not work well with the English. They ended up fighting a separate battle with Lieutenant-Admiral Adriaen Banckert. This led to arguments between the two allies. Even though both sides lost about the same number of ships, the Battle of Solebay meant the Dutch kept control of their coastal waters. It protected their trade routes and ended hopes of an Anglo-French landing in Zeeland. Anger about D'Estrées's lack of support made people more against the war. The English Parliament was unwilling to approve money for ship repairs. For the rest of the year, this limited English naval actions to one failed attack on the Dutch East India Company fleet.

The IJssel Line is Outflanked

In early June, the Dutch military headquarters at Arnhem got ready for a French attack on the IJssel Line. Only 20,000 soldiers could be gathered to stop a crossing. A dry spring meant the river could be crossed at many points. Still, it seemed like the only choice was to make a final stand at the IJssel. However, if the enemy went around this river by crossing the Lower Rhine into the Betuwe region, the army would have to fall back west. This would prevent them from being surrounded and quickly destroyed. The commander of Fort Schenkenschanz, which protected the Lower Rhine, abandoned his position. When he arrived at Arnhem with his troops, a force of 2,000 horse and foot soldiers under Field Marshal Paulus Wirtz was immediately sent to cover the Betuwe. When they arrived, they found French cavalry crossing at a shallow spot a farmer had shown them. A bloody fight followed, but in the Battle of Tolhuis on June 12, the Dutch cavalry was eventually overwhelmed by more French soldiers. Louis XIV himself watched the battle from the Elterberg. Condé was shot in the wrist. In France, this battle was celebrated as a major victory. Paintings of the Passage du Rhin often show this crossing, not the earlier one at Emmerich.

Captain-General William Henry now wanted the entire army to retreat to Utrecht. But in 1666, the provinces had regained full control of their own forces. Overijssel and Guelders provinces withdrew their troops from the main army in June 1672. The French army did not try hard to cut off the Dutch army's escape route. Turenne crossed back over the Lower Rhine to attack Arnhem. Part of his army moved to the Waal river towards Fort Knodsenburg at Nijmegen. Louis wanted to besiege Doesburg first, on the east side of the IJssel, taking it on June 21. The king delayed the capture a bit to let his brother, Philippe I, Duke of Orléans, take Zutphen a few days earlier. On his right side, the armies of Münster and Cologne, with French troops under de Luxembourg, moved north along the river. They had taken Grol on June 10 and Bredevoort on June 18. The IJssel cities panicked. Deventer left the Dutch Republic and rejoined the Holy Roman Empire on June 25. Then, the entire province of Overijssel surrendered to the Bishop of Münster, Bernard von Galen. His troops looted towns on the west side of the IJssel, like Hattem, Elburg, and Harderwijk, on June 21. Louis ordered Luxembourg to drive them out, as he wanted the Duchy of Guelders to be French. Annoyed, Von Galen announced he would move north into the Republic. He invited de Luxembourg to follow him by wading through the IJssel, as there was no bridge. Luxembourg, frustrated, got permission from Louis to keep his troops and the Cologne army separate from Münster's forces.

From then on, Von Galen fought mostly on his own. He began to besiege Coevorden on June 20. Von Galen, nicknamed "Bomb Berend," was an expert in artillery. He had invented the first practical incendiary shell, or carcass. With these fire shells, he scared the Coevorden garrison into surrendering quickly on July 1. His officers advised him to then loot the lightly defended Friesland. They also suggested using captured ships to cut off Groningen, the largest city in the north. Another option was to take Delfzijl, which would allow an English landing force to come ashore. But the bishop feared the Protestant British would join forces with the Calvinist Groningers. He expected his siege mortars would force a quick surrender. He started the Siege of Groningen on July 21.

Peace Talks and Political Changes

On June 14, William arrived at Utrecht with what was left of the army, about 8,000 men. The ordinary citizens had taken control of the city gates and refused to let him in. In talks with the city council, William had to admit he didn't plan to defend the city. He would retreat behind the Holland Water Line, a series of flooded areas protecting the main province of Holland. Eventually, the Utrecht council gave the city keys to Henri Louis d'Aloigny (Marquis de Rochefort) to avoid looting. On June 18, William pulled his forces back. The flooding wasn't ready yet, having only been ordered on June 8. The countryside of Holland was defenseless against the French. On June 19, the French took the fortress of Naarden, close to Amsterdam.

In a mood of defeat, a divided States of Holland (Amsterdam was more determined) sent a group to de Louvois in Zeist to ask for peace terms. This group was led by Pieter de Groot. They offered the French king the Generality Lands and ten million guilders. Compared to how the war actually ended, these terms were very good for France. It would have given France more land in the Low Countries than it gained until 1810. The Generality Lands included the forts of Breda, 's-Hertogenbosch, and Maastricht. Owning these would have made it much easier to conquer the Spanish Netherlands. The remaining Dutch Republic would have been almost a French puppet state. De Louvois was surprised that the Dutch had not completely given up. He demanded much harsher terms.

The Dutch were given a choice: surrender their southern forts, allow religious freedom for Catholics, and pay six million guilders. Or, France and Münster would keep their current gains (meaning the loss of Overijssel, Guelders, and Utrecht) and receive a single payment of sixteen million livres. Louis knew the Dutch delegation didn't have the power to agree to such terms and would have to return for new instructions. However, he also did not continue his advance to the west.

There are several reasons given for this. The French were quite overwhelmed by their quick success. They had captured three dozen forts in a month. This stretched their ability to organize and supply their army. Entering Holland itself seemed pointless to them unless Amsterdam could be besieged. Amsterdam would be a very difficult target. It had 200,000 people and could raise a large citizen army, helped by thousands of sailors. The city had recently expanded, so its defenses were the best in the Republic. Its normal 300 cannons were being increased by the militia moving reserve cannons from the Admiralty of Amsterdam onto the walls, which soon bristled with thousands of guns. The low-lying land around the city, below sea level, was easily flooded. This made a normal trench attack impossible. The navy could support the defenses from the IJ and Zuyderzee with gunfire. It also ensured a constant supply of food and ammunition. A deeper problem was that Amsterdam was the world's main financial centre. The promises of payment given to many French soldiers and suppliers were backed by the gold and silver in Amsterdam's banks. Losing these would cause Europe's financial system to collapse and many rich French people to go bankrupt.

Relations with England were also tricky. Louis had promised Charles II to make William Henry the ruler of a small, puppet state of Holland. Louis preferred to control it himself. But there was a chance that William's uncle, Charles II, would take control. Louis had not mentioned William in his peace terms. The very rich citizens Louis wanted to punish were traditionally pro-French. They were his natural allies against the pro-English Orangists. He wanted to simply take over Holland. He hoped that fear of the Orangists would make the regenten surrender the province to him. Of course, the opposite could also happen: a French advance might lead to the Orangists taking power and surrendering to England. The province of Zeeland had already decided they would rather have Charles as their lord than be ruled by the French. Only fear of De Ruyter's powerful fleet had stopped them from surrendering directly to the English. De Ruyter would not allow any talk of surrender. If needed, he planned to take the fleet overseas to continue the fight. Louis feared the English wanted to claim Staats-Vlaanderen. He saw this as French territory because the County of Flanders was a fief of the French crown. In secret, he arranged for a group of 6,000 men under Claude Antoine de Dreux to quickly cross officially neutral Spanish Flanders. They would make a surprise attack on the Dutch fortress of Aardenburg on June 25–26. The attempt completely failed. The small Dutch garrison killed hundreds of attackers and captured over 600 Frenchmen who got stuck in a ravelin.

Louis also let his honor be more important than what was best for his country. The harsh peace terms he demanded were meant to humiliate the Dutch. He demanded an annual visit to the French court where the Dutch would ask for forgiveness for their "treachery." They also had to present a special plaque praising the French king's generosity. For Louis, a military campaign wasn't complete without a major siege to boost his personal glory. The quick surrender of so many cities had been a bit disappointing in this way. Since Maastricht had escaped him for now, he turned his attention to an even more impressive target: 's-Hertogenbosch. This city was thought to be "unconquerable." It was not only a strong fortress itself, but it was also surrounded by a rare belt of fortifications. Normally, its marshy surroundings would make a siege impossible. But its currently weak garrison seemed to offer some chance of success. After Nijmegen was taken on July 9, Turenne captured Fort Crèvecœur near 's-Hertogenbosch. This fort controlled the water gates of the area, stopping further flooding. The main French force, now away from the Holland war zone, camped around Boxtel. Louis stayed at Heeswijk Castle.

Orangists Take Power

News that the French had entered the heart of the Dutch Republic caused widespread panic in the cities of Holland. People blamed the States government for the Dutch collapse and rioted. City council members were forced out and replaced by supporters of the House of Orange. Or, fearing punishment, they declared their support for the Prince of Orange. Leaflets accused the regenten (city leaders) of betraying the Republic to Louis XIV. They also claimed De Ruyter wanted to give the fleet to the French. When the French peace terms became known on July 1, they caused outrage.

This outrage actually strengthened Dutch resistance. On July 2, William was appointed stadtholder (chief executive) of Zeeland. On July 4, he became stadtholder of Holland. The new stadtholder, William III of Orange, was given full power to negotiate. Meanwhile, the polders of the Holland Water Line had slowly filled with water. This created a barrier against any possible French advance. Charles II thought William's rise to power would quickly lead to a peace favorable to England. He sent two of his ministers to Holland. The people welcomed them with joy, thinking they had come to save them from the French. Arriving at the Dutch army camp in Nieuwerbrug, they suggested making William the monarch of a small Holland state. In return, he should pay ten million guilders as "damages." He also had to agree to a permanent English military occupation of the ports of Brill, Sluys, and Flushing. England would respect the French and Münsterite conquests. To their surprise, William flatly refused. He said he might be more flexible if they could get the French to soften their peace terms. They then traveled to Heeswijk Castle. But the Accord of Heeswijk they agreed to there was even harsher. England and France promised never to make a separate peace. France demanded the areas of Brabant, Limburg, and Guelders. Charles tried to fix things by writing a very moderate letter to William. He claimed the only obstacle to peace was De Witt's influence. William made counteroffers that Charles found unacceptable. But on August 15, William published the letter to stir up the people. On August 20, Johan and Cornelis de Witt were killed by an Orangist citizen militia. This left William in complete control.

Seeing that the water around 's-Hertogenbosch was not going down, Louis became impatient. He lifted the siege on July 26. Leaving his main force of 40,000 men behind, he took 18,000 men and marched to Paris within a week, going straight through the Spanish Netherlands. He released 12,000 Dutch prisoners of war for a small payment. This was to avoid having to pay to keep them. Most of them rejoined the Dutch States Army, which by August had 57,000 men.

A War of Attrition Begins

In June, the Dutch seemed defeated. The Amsterdam stock market crashed, and their international credit disappeared. Frederick William, the Elector of Brandenburg, hardly dared to threaten Münster's eastern borders in these circumstances. Only one loyal ally remained: the Spanish Netherlands. They understood well that if the Dutch surrendered, they too would be lost. Although officially neutral, and forced to let the French cross their territory freely, they openly sent thousands of troops to help the Dutch.

Worry about French gains brought support from Brandenburg-Prussia, Emperor Leopold, and Charles II of Spain. Instead of a quick victory, Louis was forced into a long, drawn-out war around the French borders. In August, Turenne ended his attack against the Dutch. He went to Germany with 25,000 foot soldiers and 18,000 cavalry. Frederick William and Leopold combined their forces of about 25,000 men under the Imperial general Raimondo Montecuccoli. He crossed the Rhine at Koblenz in January 1673. But Turenne forced him to retreat into northern Germany.

The failing French attack caused financial problems for the anti-Dutch allies, especially England. Münster was in an even worse state. On August 27, it had to give up the siege of Groningen. The Dutch had managed to supply the city through waterways at its northern edge. Von Galen's troops were starving and many had deserted. This was largely due to effective guerrilla warfare by troops from Friesland under Hans Willem van Aylva against their supply lines. Also, his siege mortars had lost the artillery duel with the fortress cannons and were gradually destroyed. Before the end of 1672, the Dutch under Carl von Rabenhaupt retook Coevorden and freed the province of Drenthe. This left the Allies with only three of the ten Dutch provincial areas. The supply lines of the French army were dangerously stretched. In the autumn of 1672, William tried to cut them off. He crossed the Spanish Netherlands via Maastricht with forced marches to attack Charleroi, the starting point of the supply route through Liège. However, he had to quickly abandon the siege.

The absence of the Dutch army gave the French chances to renew their attack. On December 27, after a severe frost, Luxembourg began to cross the ice of the Water Line with 8,000 men. He hoped to loot The Hague. A sudden thaw cut his force in half. He barely escaped back to his own lines with the rest of his men. On his way back, he killed many civilians in Bodegraven and Zwammerdam. This increased hatred against Luxembourg. The province of Utrecht was one of the richest regions in Europe. The French official, intendant Louis Robert, had taken large sums of money from its wealthy residents. The French used a common method called mettre à contribution: unless rich refugees or Amsterdam merchants made regular payments, their fancy homes would be burned down. This made the general a favorite target of Dutch anti-French propaganda. Special books were published showing the terrible things he did, with illustrations by Romeyn de Hooghe. The most common Dutch school book, the Mirror of Youth, which had been about Spanish wrongdoings, was rewritten to show French atrocities.

Key Events of 1673

Before railways in the 1800s, goods and supplies were mostly moved by water. Rivers like the Lys, Sambre, and Meuse were very important for trade and military actions. France's main goal in 1673 was to capture Maastricht. This city controlled a key access point on the Meuse. The city surrendered on June 30. In June 1673, France's occupation of Kleve and a lack of money temporarily forced Brandenburg-Prussia out of the war in the Peace of Vossem.

However, in August, the Dutch, Spain, and Emperor Leopold, supported by other German states, formed the anti-French Alliance of The Hague. Charles IV of Lorraine joined in October. In September, the strong defense by John Maurice of Nassau-Siegen and Aylva in the north of the Dutch Republic finally forced Von Galen to retreat. Meanwhile, William crossed the Dutch Waterline and recaptured Naarden. In November, a 30,000-strong Dutch-Spanish army, led by William, marched into the lands of the Bishops of Münster and Cologne. The Dutch troops took revenge and committed many cruel acts. Together with 35,000 Imperial troops, they then captured Bonn. This was an important supply base in the long French supply lines to the Dutch Republic. The French position in the Netherlands became impossible to hold. Louis was forced to pull French troops out of the Dutch Republic. This deeply shocked Louis, and he retreated to Saint Germain. No one, except a few close friends, was allowed to bother him. The next year, only Grave and Maastricht remained in French hands. The war then spread into the Rhineland and Spain. Münster was forced to sign a peace treaty with the Dutch Republic in April 1674, and Cologne followed in May.

In England, the alliance with Catholic France had been unpopular from the start. Even though the true terms of the Treaty of Dover remained secret, many people suspected them. The Cabal ministry that managed the government for Charles II had hoped for a short war. But when it dragged on, public opinion quickly turned against it. The French were also accused of abandoning the English at Solebay.

Opposition to the alliance with France grew even more when Charles's heir, his Catholic brother James, was allowed to marry Mary of Modena, also a strong Catholic. In February 1673, Parliament refused to keep funding the war. They demanded Charles withdraw a proposed Declaration of Indulgence and accept a Test Act. This act would prevent Catholics from holding public office. After the Dutch defeated the Anglo-French fleet at the battles of Schooneveld and Texel that summer, and recaptured New Amsterdam from the English, pressure to end the war increased. England made peace in the Treaty of Westminster in February 1674.

These events led Louis to focus on a "policy of exhaustion." This meant emphasizing sieges, collecting war taxes, raids, and blockades, rather than large-scale battles. To support this plan, Swedish forces in Swedish Pomerania attacked Brandenburg-Prussia in December 1674. This happened after Louis threatened to stop their payments. This led to the Scanian War (1675–1679) and the Swedish-Brandenburg War. In these wars, the Swedes kept the armies of Brandenburg, Denmark, and some smaller German states busy.

Meanwhile, the French and English East India Companies had not been able to seriously weaken the strong position of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) in both intercontinental and intra-Asian trade. The VOC secured its position in Asia by defeating the French garrison in Trincomalee and the English in the Battle of Masulipatnam. They also besieged another French force in São Tomé, which fell in 1674.

War Spreads: 1674–1675

Generally, French strategy now focused on taking back Spanish lands gained in 1667–1668 but returned at Aix-La-Chapelle. They also aimed to stop Imperial advances in the Rhineland. They supported smaller campaigns in Roussillon and Sicily. These campaigns used up Spanish and Dutch naval resources.

Flanders and Franche-Comté Campaigns

In the spring of 1674, the French invaded the Spanish province of Franche-Comté. They took over the entire province in less than six weeks. French troops then joined Condé's army in the Spanish Netherlands. His army was outnumbered by the main Allied army. William invaded French Flanders, hoping to recapture the Spanish town of Charleroi and take Oudenarde. But Condé stopped him at the Battle of Seneffe. Both sides claimed victory. However, the terrible number of casualties confirmed Louis's preference for siege warfare. This led to a period where sieges and troop movements were more important than big battles.

One of the biggest problems for the Allies in Flanders was their different goals. The Imperial forces wanted to stop more troops from reaching Turenne in the Rhineland. The Spanish wanted to get back lands they had lost in the Spanish Netherlands. The Dutch were also divided by internal arguments. The powerful Amsterdam merchants wanted to end the expensive war once their business interests were safe. William, however, saw France as a long-term threat that needed to be defeated. This conflict grew once ending the war became possible with the recapture of Grave in October 1674, leaving only Maastricht.

Rhineland Battles

During the winter of 1673–1674, Turenne kept his troops in Alsace and the Palatinate. Even though England left the war in February, his army of less than 8,000 still had some English regiments. Charles II encouraged soldiers to keep serving to get money from France. Monmouth and Churchill were among those who stayed. Others joined the Dutch Scots Brigade, including John Graham, who later became Viscount Dundee.

The 1674 campaign began when Turenne crossed the Rhine in June with 7,000 men. He hoped to attack Charles of Lorraine before he could join forces with Alexander von Bournonville. At Sinsheim, the French defeated a separate Imperial army led by Aeneas de Caprara. But the delay allowed Bournonville to link up with Charles at Heidelberg. After getting more troops, Turenne began crossing the Neckar river, forcing the Imperial troops to retreat.

Bournonville marched south to the Imperial city of Strasbourg. This gave him a base to attack Alsace. But he delayed while waiting for 20,000 troops under Frederick William. To stop this, Turenne made a night march. This allowed him to surprise the Imperial army and fight them to a standstill at Entzheim on October 4. As was common practice then, Bournonville stopped operations until spring. But in his Winter Campaign 1674/1675, Turenne won a series of victories. These ended with the Turckkeim on January 5. This secured Alsace and prevented an Imperial invasion. This campaign is often considered Turenne's best work.

Command of Imperial operations in the Rhineland went to Montecuccoli. He was the only Allied general thought to be as good as Turenne. He crossed the Rhine at Philippsburg with 25,000 men. He hoped to draw the French north, then double back. But Turenne was not fooled. Instead, he blocked the river near Strasbourg to stop Montecuccoli from getting supplies. By mid-July, both armies were running out of food. Turenne tried to force the retreating Imperial army into battle. At Salzbach on July 27, he was killed by a stray cannonball while scouting the enemy's positions. His death discouraged the French. They withdrew after some small fights and fell back to Alsace. Montecuccoli pursued them. He crossed the Rhine at Strasbourg and besieged Hagenau. Another Imperial army defeated Créquy at Konzer Brücke and recaptured Trier. Condé was sent from Flanders to take command. He forced Montecuccoli to withdraw across the Rhine. However, poor health forced Condé to retire in December, and Créquy replaced him.

Spain and Sicily

Fighting on this front was mostly small skirmishes in Roussillon. A French army under Frederick von Schomberg fought Spanish forces led by the Duque de San Germán. The Spanish won a small victory at Maureillas in June 1674. They also captured Fort Bellegarde, which had been given to France in 1659. Schomberg retook it in 1675.

In Sicily, the French supported a successful revolt by the city of Messina against its Spanish rulers in 1674. This forced San Germán to move some of his troops there. A French naval force under Jean-Baptiste de Valbelle managed to resupply the city in early 1675. They also gained control of the local seas.

At sea, after making peace with England, the Dutch fleet could now be used for attacks. De Ruyter tried an attack on the French Caribbean islands. But he was forced to retreat without achieving anything. A Dutch fleet under Cornelis Tromp operated along the French coast. Tromp led a landing on June 27 on the island of Belle Île, off the coast of Brittany. He captured its coastal defenses. However, the Dutch left the island after two days. This was because the 3,000 French defenders had taken refuge in the island's strong fortress. A siege would have taken too long. A few days later, on July 4, the island of Noirmoutier was attacked. After a short fight, which left more than a hundred Dutch men out of action, the French retreated to Poitou. They left the island, with its castle, coastal batteries, over 30 cannons, and several ships, in Dutch hands. For nearly three weeks, the Dutch flag flew from the walls of the French stronghold. The Dutch fleet captured many French ships during this time. The entire coastline from Brest to Bayonne was in chaos. Several strong French forces gathered to stop the Dutch from landing. On July 23, the island of Noirmoutier was abandoned. The Dutch blew up the castle and destroyed the coastal batteries. The French coast remained fearful for some time. But after visiting the Mediterranean, Tromp's fleet returned to Holland at the end of 1674.

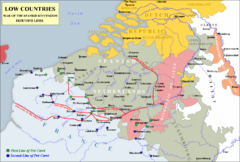

Negotiating Peace: 1676–1678

For both sides, the last years of the war brought very little return for the men and money they spent. French strategy in Flanders was mostly based on Vauban's idea for a line of forts called the Ceinture de fer or iron belt (see Map). This fit with Louis's preference for siege warfare. This preference grew stronger after Turenne's death and Condé's retirement. Their loss meant France no longer had two of its most talented and aggressive generals of the 17th century. These were the only ones strong enough to challenge the king. The French were preparing a major attack at the end of 1676. It aimed to capture Valenciennes, Cambrai, and Saint-Omer in the Spanish Netherlands. After this, the Ceinture de fer would be mostly complete. Louis believed this would make the Dutch leaders lose courage and stop the war. However, he was wrong. The coming French attack actually made the Dutch and Spanish work together more closely. Still, the French attack of 1677 was a success. The Spanish found it hard to raise enough troops due to money problems. The Allies were defeated in the Battle of Cassel. This meant they could not stop the cities from falling to the French. The French then took a defensive stance. They were afraid that more success would force England to join the Allies.

In Germany, Imperial forces captured Philippsburg in September 1676. But the French stabilized their front. Créquy's movements countered Imperial attacks by Charles V of Lorraine. The French commander succeeded in capturing Freiburg in November 1677. Defeating the Imperials at Rheinfelden and Ortenbach in July 1678 ended their hopes of retaking the city. The French then captured Kehl and the bridge over the Rhine near Strasbourg. This secured their control of Alsace. The Spanish front remained mostly unchanged. A French victory at Espolla in July 1677 did not change the overall situation. But their losses worsened the crisis faced by the Spanish government.

To help Spain defend Sicily, the Dutch Republic sent a small fleet under De Ruyter to the Mediterranean Sea. De Ruyter did not approve of the operation. He thought his fleet was too small to change the balance of power in the Mediterranean, where the French were very strong. Under pressure from the admiralty, he accepted command anyway. His doubts would soon be proven right. But not before he pushed back an attack by a stronger French fleet under Abraham Duquesne at Stromboli. Several months later, in April 1676, De Ruyter repeated this feat at the Battle of Augusta. But he was fatally wounded during the battle. The French would gain control of the Western Mediterranean Sea. This happened after their galleys surprised the Dutch/Spanish fleet at anchor at Palermo in June. However, French involvement had been opportunistic. Problems arose with the anti-Spanish rebels. The cost of operations was too high, and Messina was evacuated in early 1678.

In Northern Germany, the Swedish position crumbled. By 1675, most of Swedish Pomerania and the Duchy of Bremen had been taken by the Brandenburgers, Imperials, and Danes. In December 1677, the Elector of Brandenburg captured Stettin. Stralsund fell on October 11, 1678. Greifswald, Sweden's last possession on the continent, was lost on November 5. Swedish naval power was destroyed by the Danish and Dutch fleets under Niels Juel and Cornelis Tromp after the battles of Battle of Öland and Battle of Køge Bay. But the Danish invasion of Scania was less successful. After the very bloody Battle of Lund and the Battle of Landskrona, Danish forces were sent back to Denmark.

Peace talks began at Nijmegen in 1676. They became more urgent in November 1677 when William married his cousin Mary, who was Charles II of England's niece. An Anglo-Dutch defensive alliance followed in March 1678. However, English troops did not arrive in large numbers until late May. Louis used this chance to improve his negotiating position. He captured Ypres and Ghent in early March. Then, he signed a peace treaty with the Dutch on August 10.

The Battle of Saint-Denis was fought three days later on August 13. A combined Dutch-Spanish force attacked the French army under Luxembourg. The French were forced to retreat, which ensured that Mons remained in Spanish hands. On August 19, Spain and France agreed to a ceasefire. A formal peace treaty followed on September 17.

Peace and Its Effects: The Treaties of Nijmegen

Louis XIV's two main goals, destroying the Dutch Republic and conquering the Spanish Netherlands, were not fully achieved. Still, the Peace of Nijmegen confirmed most of the land France had gained in the later parts of the war. Louis, having successfully fought a powerful group of enemies, became known as the 'Sun King' in the years after the conflict. France returned Charleroi, Ghent, and other towns in the Spanish Netherlands. In return, France received all of Franche-Comté and the towns of Ypres, Maubeuge, Câteau-Cambrésis, Valenciennes, Saint-Omer, and Cassel. Except for Ypres, all of these are still part of France today. While good for France and leading to lasting gains, the peace terms were much worse than those available in July 1672.

The Dutch recovered from the near disaster of 1672. They proved they were a significant power in Northern Europe. They ended the war without losing any of their own territory. They also got France to leave several advanced positions captured in 1668. And France repealed the strict customs tax of 1667, which Jean-Baptiste Colbert had designed to hurt Dutch trade. Perhaps their most lasting gain was William's marriage to Mary. He became one of the most powerful leaders in Europe, strong enough to keep an anti-French alliance together. The war also showed that while many English merchants and politicians were against the Dutch for business reasons, there was no popular support in England for an alliance with France. However, the beneficial separate peace, signed against William's wishes, put the Republic's allies in a worse position. For years afterward, the Republic was seen as an untrustworthy ally, only caring about its own business interests. The war had also seen the rebirth of the Dutch States Army. It became one of the most disciplined and well-trained armies in Europe. William and the Dutch leaders mostly blamed the Spanish for the fact that this was not enough to stop France from conquering parts of the Spanish Netherlands. The Dutch had expected more military strength from the once-powerful Spanish Empire.

In Spain, defeat led to the Queen Regent, Mariana of Austria, being replaced by her long-time rival, the pro-French John of Austria the Younger. She returned to power after his death in September 1679. But not before he arranged the marriage of Charles II of Spain to Louis's niece, 17-year-old Marie Louise of Orléans in November 1679.

Brandenburg managed to fully occupy Swedish Pomerania in September 1678. But France's ally Sweden got it back through the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye in 1679. This did little to improve Sweden's dangerous financial situation. Also, Frederick William was angry about being forced to give up what he saw as his own territory. This turned Brandenburg-Prussia into a strong opponent of France.

Louis had huge advantages: excellent commanders, better logistics, and a single strategy. This was unlike his opponents, who had different goals. At the same time, the war showed that the threat of French expansion was more important than anything else for rival nations. It also showed that France, even though it was Europe's greatest power, could not easily force its will against a group of allied countries. French forces would soon capture Strasbourg (in 1681) and win in the short War of the Reunions (1683–1684). This only made other European states more angry. It led to the creation of the anti-French Grand Alliance in 1688. This alliance largely stayed together through the Nine Years' War (1688–1697) and the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714).

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Guerra franco-neerlandesa para niños

In Spanish: Guerra franco-neerlandesa para niños

- List of Dutch structures damaged by the French (1672–1673)

- Louis XIV Victory Monument (Place des Victoires, Paris)

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |