Swedish invasion of Brandenburg facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Swedish invasion of Brandenburg |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Scanian War (Northern Wars) Franco-Dutch War |

|||||||

Battle of Fehrbellin by Dismar Degen. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Swedish Empire | Brandenburg-Prussia | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Carl Gustaf Wrangel Waldemar von Wrangel |

Frederick William Georg von Derfflinger |

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| January 1675: 13,000–13,700 May 1675: 11,000–12,000 |

Garrison troops: 5,000 Relief force: 15,000 |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| June–July 1675: 4,000 (1,100–1,500 combat losses) |

June–July 1675: Unknown (600–1,000 combat losses) |

||||||

The Swedish invasion of Brandenburg happened between 1674 and 1675. A Swedish army from Swedish Pomerania marched into Brandenburg, a region in Germany, which was not defended at the time. This invasion started a bigger conflict called the Swedish-Brandenburg War. This war then grew into a larger European conflict that lasted until 1679.

The main reason for the Swedish invasion was that Brandenburg had sent its army to help fight France in the Franco-Dutch War. Sweden was an ally of France. So, Sweden invaded Brandenburg to force its leader, the Elector of Brandenburg, to stop fighting France.

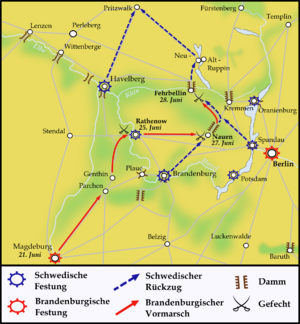

In June 1675, the Elector and his 15,000 soldiers marched from southern Germany to Magdeburg. They quickly moved against the Swedish army, which had about 11,000 to 12,000 men. After just one week, the Swedish troops had to leave Brandenburg.

Contents

Why Did the Swedish Invasion Happen?

France's Plan and Alliances

After an earlier war, King Louis XIV of France wanted to get back at the States-General (the government of Holland). He made a secret agreement with Sweden in 1672. This deal said that Sweden would send 16,000 soldiers to fight any German state that helped Holland.

Soon after, in June 1672, Louis XIV invaded Holland. This started the Franco-Dutch War. The Elector of Brandenburg decided to help Holland with 20,000 soldiers.

In 1673, Brandenburg and Sweden made a defensive alliance. This meant they would protect each other. Because of this, the Elector of Brandenburg did not think Sweden would join the war on France's side.

However, Brandenburg rejoined the war against France in 1674. This happened when the Holy Roman Empire declared war on France.

Sweden's Reasons for Invading

On August 23, 1674, Brandenburg's army of 20,000 men marched towards Strasbourg. The Elector, Frederick William, and his son went with the army. John George II of Anhalt-Dessau was left in charge of Brandenburg as its governor.

France then paid Sweden money and promised other help. This convinced Sweden to join the war against Brandenburg. Sweden had been helped by France before, so they were allies. Sweden's leaders were worried that if France lost, Sweden would be left alone.

Sweden's goal was to take over Brandenburg, which was left without its main army. They hoped this would force Brandenburg to bring its troops back from the war against France.

Getting Ready for War

| Key Dates: 1674

1675

|

Sweden started gathering its army in Swedish Pomerania. Reports of these troop movements reached Berlin in September. The Governor of Brandenburg heard that about 20,000 Swedish soldiers would be ready by the end of the month. News of an attack grew stronger when the Swedish commander, Carl Gustav Wrangel, arrived in Wolgast in October.

The Governor, John George II, was worried. He asked Carl Gustav Wrangel why the troops were moving. But Wrangel did not answer. By mid-November, the Governor was sure an invasion was coming. However, the exact reasons for the attack were still unclear in Berlin.

Despite the worrying news, Elector Frederick William did not believe Sweden would invade. He wrote a letter on October 31, 1674, saying he thought the Swedes were "better than that" and would not do "such a dastardly thing."

Swedish Army Strength

Before entering Brandenburg in December 1674, the Swedish invasion army had:

- Infantry (foot soldiers): 11 regiments with 7,620 men.

- Cavalry (horse soldiers): 8 regiments with 6,080 men.

- Artillery: 15 cannons.

Brandenburg's Defenses

After its main army left for Alsace, Brandenburg had very few soldiers left. Most were old or injured. The few healthy soldiers were in fortresses. In August 1674, the Governor had only about 3,000 men. Berlin, the capital, had only 500 older soldiers and 300 new recruits.

So, Brandenburg immediately started recruiting new soldiers. The Elector also ordered a general call-up for farmers and townspeople to help defend their homes. This old law meant citizens could be used for local defense. By December 1674, this call-up helped gather about 1,300 men in Berlin and nearby towns. More troops arrived from western provinces in January 1675.

The Campaign Begins

Swedish Invasion and Occupation (December 1674 – April 1675)

On December 25, 1674, Swedish troops marched into the Uckermark region of Brandenburg. They did this without officially declaring war. The Swedish commander, Carl Gustav Wrangel, said his army would leave if Brandenburg stopped fighting France. Sweden did not want a full break in relations with Brandenburg.

The Swedish army had between 13,000 and 13,700 men and 15 cannons. Carl Gustav Wrangel, who was over 60 and often sick, had other field marshals helping him. However, their unclear roles made it hard to give clear orders, slowing down the army's movements.

Many European countries watched closely. Sweden's military power, famous from the Thirty Years' War, seemed very strong. German soldiers were eager to join the Swedes. Some German states even joined the Swedish-French alliance.

The Swedish army set up its main camp in Prenzlau. Another group of Swedish soldiers joined them there.

Meanwhile, Brandenburg's main army was in winter camps in southern Germany. The Elector decided not to send them back immediately because of the cold weather and their losses. A sudden withdrawal would also have pleased France, which was Sweden's goal.

Brandenburg could not hold the open areas east of the Oder River. But the central part of Brandenburg could be defended with fewer troops. This was because it had natural defenses like marshlands and rivers. Brandenburg's defenses were set up along a line from Köpenick to Havelberg. The Spandau Fortress was strengthened with 800 men and 24 cannons. Berlin's defense grew to 5,000 men.

However, the Swedes did not act quickly. They did not take advantage of Brandenburg's main army being away. Instead, they focused on collecting money from the occupied areas and building up their army. This slowness was partly due to disagreements within the Swedish government.

In late January 1675, Carl Gustav Wrangel moved his forces. On February 4, he crossed the Oder River into Pomerania and the Neumark. Swedish troops occupied several towns like Stargard in Pommern and Landsberg. Wrangel then set up winter camps for his army in these areas.

When it became clear that Brandenburg would not leave the war, Sweden ordered a stricter occupation. This meant more harsh treatment of the people and the state. Many people at the time said these actions were worse than during the Thirty Years' War. Still, there was no major fighting until spring 1675. The Governor described this time as "neither peace nor war."

Swedish Spring Attack (May – June 1675)

In early May 1675, the Swedes began their spring attack. They had recruited more soldiers but also lost some to sickness and desertion. By May 10, their army had shrunk to between 11,000 and 12,000 men.

Wrangel wanted to cross the Elbe River to meet other Swedish forces. This would cut off the Elector's army from reaching Brandenburg. The Swedish army moved through Stettin. Even though their army was not as strong as before, people still saw Sweden as a mighty military power. This helped them succeed at first.

The first fighting happened at Löcknitz. On May 15, 1675, a fortified castle there surrendered to the Swedes after one day of shelling. The commander of the castle was later sentenced to death for this.

After taking Löcknitz, the Swedes quickly moved south. They occupied towns like Neustadt and Bernau. Their next target was the Rhinluch, a marshy area with only a few crossing points. Brandenburg had placed armed farmers and rangers to guard these points. The Governor sent more troops and cannons from Berlin to help defend these passes.

The Swedes advanced in three groups. One group went towards Oranienburg, another towards Kremmen, and the strongest group (2,000 men) went towards Fehrbellin. There was heavy fighting at Fehrbellin for several days. Since the Swedes could not break through there, they found another crossing near Oranienburg with help from local farmers. About 2,000 Swedes crossed there. This forced Brandenburg to abandon its positions at Kremmen, Oranienburg, and Fehrbellin.

Soon after, the Swedes tried to storm Spandau Fortress but failed. The entire Havelland region was now under Swedish control. Their main camp was first in Brandenburg town. After taking Havelberg, the Swedish camp moved to Rheinsberg.

Field Marshal Carl Gustav Wrangel became very sick with gout. His stepbrother, Lieutenant General Wolmar Wrangel, took over command. This caused problems among the generals, leading to a loss of discipline. Soldiers began looting and mistreating civilians. The Swedes also lost two valuable weeks trying to cross the Elbe River.

On June 19, Carl Gustav Wrangel, still sick, reached Neuruppin. He immediately stopped the looting and sent scouts towards Magdeburg. On June 21, he went to Havelberg to prepare for crossing the Elbe. He ordered all available boats to build a bridge.

At the same time, he told Wolmar Wrangel to bring the main army to Havelberg via Rathenow. The main army was in Brandenburg an der Havel. The connection between Havelberg and Brandenburg an der Havel was guarded by only one regiment at Rathenow. This weak point was a good target for an enemy attack. By June 21, most of Brandenburg was in Swedish hands. However, the planned Swedish crossing of the Elbe at Havelberg never happened.

Meanwhile, Elector Frederick William sought allies. He knew his own forces were not enough to fight Sweden alone. He went to The Hague for talks in March, arriving in May. Holland and Spain declared war on Sweden because of the Elector's urging. But he got no real help from the Holy Roman Empire or Denmark. So, the Elector decided to take Brandenburg back from the Swedes by himself. On June 6, 1675, he gathered his army and began marching towards Magdeburg. His 15,000-strong army advanced in three groups.

Elector Frederick William's Campaign (June 23–29, 1675)

On June 21, the Brandenburg army reached Magdeburg. The Swedes did not seem to know they were there. Frederick William kept this a secret. At Magdeburg, he learned that Swedish and Hanoverian troops planned to join forces and attack Magdeburg. After a meeting, the Elector decided to break through the Swedish lines at their weakest point, Rathenow. He wanted to separate the two parts of the Swedish army.

On June 23, around 3 a.m., the army left Magdeburg. To keep the surprise, the Elector only took his cavalry (5,000 horsemen and 600 dragoons). He also had 1,350 musketeers on wagons to keep them moving fast. They had 14 cannons. The Elector and the 69-year-old Field Marshal Georg von Derfflinger led this army.

On June 25, 1675, the Brandenburg army reached Rathenow. Field Marshal Georg von Derfflinger personally led the attack. They defeated the Swedish soldiers there in fierce street fighting.

That same day, the main Swedish army marched from Brandenburg an der Havel to Havelberg. They planned to cross the Elbe there. But the capture of Rathenow changed everything. The two Swedish armies were now separated, and crossing the Elbe at Havelberg was no longer possible. Field Marshal Carl Gustav Wrangel, who was in Havelberg without supplies, ordered the main Swedish army under Wolmar Wrangel to join him via Fehrbellin. So, Carl Gustav Wrangel left for Neustadt on June 26.

The Swedish leaders seemed unaware of where the Brandenburg army was or how strong it was. Lieutenant General Wolmar Wrangel quickly moved north to protect his communication lines and meet the separated Swedish advance guard. On June 25, the Swedes were at Pritzerbe. From there, they had only two ways to go because of the difficult terrain. The shorter path was risky due to Brandenburg troops. So, the Swedes chose to retreat through Nauen to Fehrbellin.

The Elector immediately split his forces into three groups to block the only three passes. These groups were sent to Fehrbellin, Kremmen, and Oranienburg. Their job was to get ahead of the Swedes using secret routes through the swamps. They were to destroy bridges and block roads. Local armed groups and hunters would help defend these points.

One group, led by Lieutenant Colonel Hennig, rode through the swamps to Fehrbellin. They surprised and attacked 160 Swedish horsemen guarding the causeway. About 50 Swedes were killed, and 10 Brandenburg soldiers were lost. The Brandenburg soldiers then burned the two bridges and broke the causeway. This cut off the Swedes' retreat to the north.

Since there was no order to hold the pass at all costs, the Brandenburg group tried to rejoin the main army. They arrived back on June 27. Their reports, and those from the other groups, convinced the Elector to fight a major battle against the Swedes.

On June 27, the first fight happened between the Swedish rear guard and Brandenburg's front group. This was the Battle of Nauen, and Brandenburg recaptured the town. By evening, the two main armies were ready for battle. However, the Swedish position seemed too strong, and Brandenburg's troops were tired from forced marches. So, the Elector ordered his army to camp in Nauen. Brandenburg expected the main battle to start the next morning. But the Swedes used the cover of night to retreat towards Fehrbellin. From June 25 to after the Battle of Nauen on June 27, the Swedes lost about 600 men and another 600 were captured during their retreat.

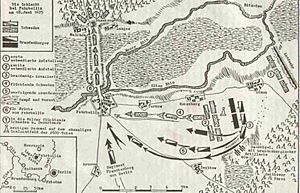

Because the causeway and bridge at Fehrbellin were destroyed, Sweden was forced to fight the Battle of Fehrbellin. Lieutenant General Wolmar Wrangel had at most 7,000 men and seven cannons. The rest of his army was elsewhere.

The Swedes were defeated but managed to cross the repaired bridge under the cover of night. They lost 600 killed and wounded, while Brandenburg lost 500. The Swedes destroyed the bridge behind them, stopping Frederick's army from chasing them effectively. The retreat continued through other regions. Brandenburg cavalry caught up with the Swedish rear guard but were pushed back. Another attempt near Wittstock also failed. After this, Brandenburg stopped chasing them. Many Swedish soldiers deserted during the quick retreat.

What Happened Next?

On July 7, the Swedish army reached Swedish territory. It had only 7,000 men left, down from 11,000–12,000 at the start of their spring attack. The rest were killed, captured, wounded, sick, or had run away. By the end of July, their numbers were slightly higher, possibly due to new recruits or returning soldiers. In total, Sweden lost about 4,000 men since June, with about 1,100–1,500 lost in combat.

Brandenburg's total losses are not fully known, but they were fewer than Sweden's. They had between 600 and 1,000 combat losses.

The Swedish defeat at Fehrbellin had big consequences. It broke the idea that Sweden's army was unbeatable. The remaining Swedish soldiers were back in Swedish Pomerania, where they had started the war.

Sweden's situation got worse when Denmark and the Holy Roman Empire also declared war on them. Sweden's lands in northern Germany were now in danger. In the years that followed, Sweden had to focus on defending its own territories. In the end, they only managed to keep Scania.

France's plan, however, worked. Brandenburg-Prussia was still officially at war with France, but its army had left the Rhine front. Now, Brandenburg had to focus all its efforts on fighting Sweden.

Images for kids

| Precious Adams |

| Lauren Anderson |

| Janet Collins |