Siege of Maastricht (1673) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Siege of Maastricht |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Franco-Dutch War | |||||||

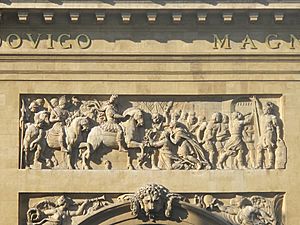

Louis XIV in front of the besieged city |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 24,000 infantry 16,000 cavalry 58 guns |

5,000 infantry 1,200 cavalry |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 2,300+ | 1,700 | ||||||

The Siege of Maastricht happened from June 15 to June 30, 1673. It was part of the Franco-Dutch War (1672-1678). During this time, a French army captured the important Dutch fortress city of Maastricht. The city was very important because of its location on the Meuse river. Capturing it was France's main goal for 1673. Maastricht was later given back to the Dutch in 1678, as part of the Treaty of Nijmegen.

This siege was led by the famous French military engineer Vauban. It's believed to be the first time a new technique called the "siege parallel" was used. This method of attack was used in wars for a very long time, even until the mid-1900s. A famous person who died during the siege was Charles de Batz de Castelmore d'Artagnan. He is thought to be the real person who inspired the main character in Alexandre Dumas' famous book, The Three Musketeers.

Contents

Why the Siege Happened

In an earlier war (1667-1668), France had taken some land from the Spanish Netherlands. But other countries, like the Dutch Republic, England, and Sweden, formed an alliance. They made France give back most of the land.

King Louis XIV of France wanted to try again to gain more territory. So, he made deals with other countries. He paid Sweden to stay neutral. England also agreed to be allies with France against the Dutch in a secret agreement in 1670.

In May 1672, the French army invaded the Dutch Republic. At first, it looked like France would win easily. They captured important fortresses and took over Utrecht without a fight. But by July, the Dutch set up a strong defense line called the Dutch Water Line. Other countries, like Brandenburg-Prussia, the Holy Roman Empire, and Spain, started to support the Dutch. This forced King Louis XIV to split his army.

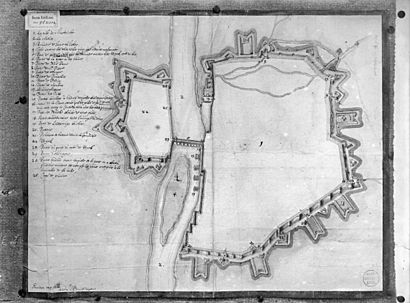

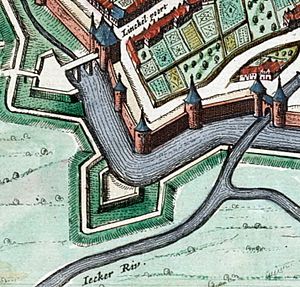

Maastricht was very important because it controlled the Meuse river valley. It was one of several strong fortress cities along the river. The Dutch had captured Maastricht in 1632. Its defenses were made much stronger over the years.

Because of its location, Maastricht was a key city. The French had set up supply bases nearby. The Dutch had placed 11,000 soldiers in Maastricht. They hoped that if the French tried to besiege the city, it would give them time to prepare other defenses.

The French reached Maastricht in May 1672 but bypassed its main defenses. This allowed them to take other fortresses. However, keeping Maastricht allowed the Dutch to threaten French supply lines. In November 1672, William III of Orange used Maastricht as a base to attack Charleroi, a French-held city.

Because of this, capturing Maastricht became the main goal for France in 1673. King Louis XIV himself joined the army. He liked sieges because they were a good way to show off his power and glory. He even had a life-size fortress built in his royal gardens when he was a boy to practice sieges.

Louis XIV moved his army towards Maastricht. The siege officially began on June 15, when the first trenches were dug.

New Ways to Attack a City

Maastricht was the first siege where Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban was in charge of the operations. Before this, he was mostly an advisor. Vauban was not a military commander, so he had to follow King Louis XIV's orders. Louis XIV didn't want his best generals there. He wanted all the glory for himself. Louis often visited the trenches, even when it was dangerous. Painters and poets followed him to record his brave acts.

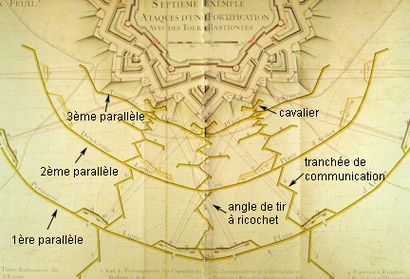

Vauban is famous for building strong forts. But his biggest ideas were about how to attack cities. He wrote down his ideas on siege warfare. The "siege parallel" method had been developing for a while. But at Maastricht, Vauban made it work perfectly.

Here's how it worked:

- Soldiers dug three long trenches that ran parallel to the city walls.

- These trenches were connected by other trenches that went towards the city.

- The dirt from digging was used to build high banks. These banks protected the attacking soldiers from enemy fire.

- The trenches allowed a large number of soldiers to get very close to the city walls safely.

- Artillery (cannons) could be moved into these trenches. This allowed them to shoot at the base of the walls from close range. The defenders couldn't aim their own guns low enough to hit them.

- Once a hole (breach) was made in the wall, the soldiers would storm it.

This method became the standard way to attack cities until the early 1900s. Vauban's work required many workers. About 20,000 local farmers were forced to dig the trenches at Maastricht.

Soldiers on Both Sides

The King of England, Charles II, had agreed to send 6,000 English and Scottish soldiers to help the French army. He also secretly received money from France for this. Charles II wanted to show Louis XIV that his troops were useful. Some English officers, like the Duke of Monmouth and John Churchill (who later became a famous general), were at Maastricht as volunteers. Louis XIV gave them important roles to please his English ally. The French attacking force had about 40,000 soldiers.

The Dutch city was defended by Jacques de Fariaux. He was an experienced French Huguenot (Protestant) who served the Dutch. Many Dutch soldiers had been moved from Maastricht before the siege. In June 1673, about 5,000 Dutch soldiers and 1,200 cavalry remained. They were joined by a Spanish group of soldiers. The total number of defenders was about 5,000. This was less than what the city needed for a good defense.

The city's defenses had been neglected for a long time. They were mostly earthworks that could easily fall apart. Some quick repairs were made in 1672 and 1673, but they only helped a little. Wooden fences were built to make weak spots stronger. A new small fort (a lunette) was added in front of the Tongeren Gate, which was a weak point.

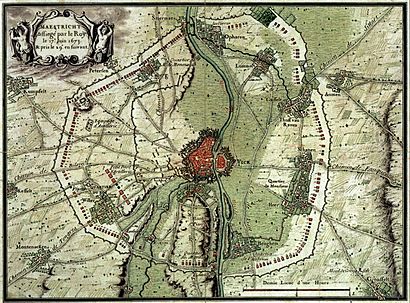

The Siege Begins

On June 5, the first French soldiers arrived at Maastricht. The next day, more French troops appeared on the other side of the river. On June 7, the French started building two bridges made of ships to connect their forces. At the same time, about 7,000 farmers began digging trenches around the city. The Dutch defenders tried to attack the French on June 7 and June 9, killing a few French soldiers. King Louis XIV arrived on June 10. He asked de Fariaux to surrender the city, but de Fariaux refused.

On June 13, the French started preparing wood and digging tools on the west side of the city. The north of the fortress was protected by a deep moat connected to the river. The south was protected by a small river that could flood trenches. So, the best way to attack was from the west. This side had two main gates: the Brussels Gate and the Tongeren Gate. Digging trenches here was hard because of the rock, but it was possible.

By June 14, the trenches around the city were mostly finished. On June 16, the French placed their cannons. Two were in front of the Tongeren Gate, and one was on a hill called St Pietersberg. The cannons immediately started firing, shooting 3,000 times in the first six hours. It became clear that the Tongeren Gate was the main target. It was a weak spot because it had only a small fort (a ravelin) in front of it. The city wall behind it was old and not very strong.

On June 17, at 9 PM, the French started digging two attack trenches towards the Tongeren Gate. They worked quickly in the dark. By the next day, the first parallel trench was finished. On June 19 and 20, the second parallel trench was built. De Fariaux thought about attacking the trenches to destroy them but decided against it because they were too big and had cannons.

The French cannons destroyed the wooden fences and silenced the Dutch cannons. They made small holes in the main wall. This made the people in the city very nervous. Traditionally, soldiers could loot a city if its walls were broken. On June 23, the attack trenches got very close to the city's defenses. During the night of June 23/24, the third parallel trench was finished. About 2,500 soldiers gathered there to storm the gate.

The Attack

A rumor spread in the city that King Louis XIV wanted to end the siege quickly. He supposedly wanted to celebrate a religious holiday in the city's church on June 24. At 5 PM, five cannon shots signaled the start of the attack. First, the French attacked Wijck, a suburb on the other side of the river. This was a trick to draw away Dutch defenders.

The main attack force at the Tongeren Gate was split into three parts. The Marquis de Montbrun led the main attack against the lunette. There were two other attacks to distract the defenders. One was led by Charles de Montsaulnin, Comte de Montal, against another fort called the Groene Halve Maan. The Duke of Monmouth led the attack on the left. This group included about 50 English volunteers and a company of King's Musketeers, led by Captain-Lieutenant D'Artagnan. They attacked a fort called the hornwork. King Louis had tried to stop Monmouth from fighting, fearing he might die. But he finally gave permission.

Vauban had ordered that the smaller attacks should only be feints (fake attacks). But Monmouth tried to climb the hornwork and was pushed back with heavy losses. Over 100 of his soldiers were killed or wounded. The French also lost many soldiers in other areas. The lunette was captured, then recaptured by the Dutch, and then taken again by the French.

Part of the city's defenses included tunnels dug under the ground. These tunnels had partly collapsed, but some quick repairs were made before the siege. On the morning of June 25, as French soldiers were being replaced, the Dutch set off a mine under the lunette. About 50 attackers were killed. The Dutch then rushed out and recaptured the lunette for a second time.

In response, the British and French attacked again. Monmouth went around the lunette from the left, and D'Artagnan from the right. The Musketeers attacked from the front. After a confused fight, the Dutch were pushed back. Several English officers were killed or wounded, including Churchill. D'Artagnan was hit in the head by a bullet and died while passing through a broken fence. Out of 300 musketeers, over 80 were killed and more than 50 were badly wounded. Later, a new fort built there was named "demilune des mousquetaires" in their honor.

Vauban became worried. He thought the Dutch soldiers had low morale, but they were fighting harder than expected. He wrote to the French war minister, saying that if the Dutch recaptured the lunette a third time, the French might have to give up the siege. The attackers had a weak hold on the lunette. It would take them hours to bring in more soldiers. However, the Dutch did not make another attack.

On June 26 and 27, the French reorganized their attack teams. They decided that before storming the fort in front of the gate, they needed to capture the hornwork and the Groene Halve Maan. This would stop the Dutch from firing at them from the side. Cannons were placed to bombard these forts. On June 27, King Louis XIV watched the bombardment of the city for hours.

French engineers dug a tunnel under the hornwork. On the night of June 27/28, they set off a mine. The Italian defenders panicked, and the French climbed over the walls. The defenders fought back with hand grenades but were forced to leave the fort to the French. The French captured some Dutch engineers who told them where other mines were. Before the French could enter the tunnels, the Dutch blew up five more mines under the hornwork. The French prepared for another Dutch attack, but none happened. The Dutch soldiers were too weak now.

On June 28, some citizens asked de Fariaux to surrender. Another cannon battery was placed opposite the gate. On the night of June 28/29, French soldiers sneaked into the ravelin and found it had been abandoned.

The City Surrenders

On June 29, a French trumpeter again asked the city to surrender. De Fariaux refused again. So, the French cannons fired even more intensely at the city and its defenses. The cannons on the St Pietersberg hill focused their fire on the southwest corner of the city wall. The wall collapsed into the moat. The Dutch abandoned the Groene Halve Maan fort during the night of June 29/30.

The situation for the Dutch soldiers was hopeless. The people of Maastricht put strong pressure on de Fariaux to stop fighting. They reminded him of the Siege of Maastricht in 1579. In that siege, Spanish troops had looted the city and killed many people. The citizens begged him to prevent such a tragedy from happening again.

In the early morning of June 30, de Fariaux sent a message that he was ready to talk. After two hours, he surrendered the city. The terms were quite good for the Dutch. The soldiers were allowed to leave freely, with their drums beating and flags flying. They marched to the nearest Dutch-held territory, 's-Hertogenbosch. This group included Van Coehoorn, who had been wounded during the siege. There would be no looting of the city.

Maastricht was a city shared by the Dutch Republic and the Bishopric of Liège. The Bishop of Liège was an ally of King Louis XIV. Louis XIV also wanted Maastricht to be a permanent French possession. Right after the surrender, two French regiments occupied the gates of the city. Louis XIV made a grand entry through the Brussels Gate.

Both sides had many losses. The number of Dutch soldiers who reached 's-Hertogenbosch was 3,118. If there were 5,000 defenders, about 1,700 Dutch soldiers were killed or wounded. Estimates for French losses vary. Some say 900 dead and 1,400 wounded. Others say about twice the number of Dutch casualties. Some Dutch accounts at the time claimed 6,000 French killed and 4,000 wounded.

What Happened Next

The quick fall of Maastricht meant King Louis XIV had extra time. To keep his army busy, he attacked the Electorate of Trier without declaring war. He claimed the bishop had allowed some enemy troops to enter. The city of Trier was besieged and largely destroyed.

William III of Orange had feared that other Dutch cities would be attacked next. He had gathered an army of 30,000 soldiers to help any city under attack. The French had thought about attacking 's-Hertogenbosch but decided against it because the marshy land made success difficult.

Even though losing Maastricht was a blow to Dutch morale, the siege of Trier helped them. People in German states were angry about France's actions. The Holy Roman Emperor moved his army into the Rhineland. In response, Louis XIV pulled most of his troops away from the Dutch Water Line. This weakened his control over other Dutch areas.

Soon after Maastricht fell, the Dutch made a treaty with the Holy Roman Emperor and Spain in August 1673. This created a new alliance. In October, Denmark also joined. At the Water Line, William III of Orange recaptured the fortress town of Naarden on September 13. As the war spread, French troops left the Dutch Republic, keeping only Grave and Maastricht. Grave was recaptured by the Dutch in 1674.

The alliance between England and Catholic France was not popular in England. In early 1674, Denmark joined the alliance against France. England and the Dutch made peace in the Treaty of Westminster.

William III tried to recapture Maastricht in 1676 but failed. The French had greatly improved the city's defenses using Vauban's plans. Vauban spent three weeks studying the city to create detailed maps. A large model of the fortress was also made.

On September 16, 1673, the French war minister wrote that Louis XIV would rather give up Paris than Maastricht. But the city was returned to the Dutch when the Treaty of Nijmegen ended the war in 1678. The Dutch had promised to give the city to the Spanish Netherlands after a victory. But they refused once peace was signed, saying it would break the treaty.

The siege was shown in paintings by Charles Le Brun on the ceiling of the Hall of Mirrors in Versailles. Adam Frans van der Meulen also painted a series of pictures about the event. Louis XIV had the Porte Saint-Denis (a famous arch in Paris) redesigned to remember this siege. A plaque on it says, "To Louis the Great, for capturing Maastricht in thirteen days."

See also

In Spanish: Sitio de Maastricht (1673) para niños

In Spanish: Sitio de Maastricht (1673) para niños

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |