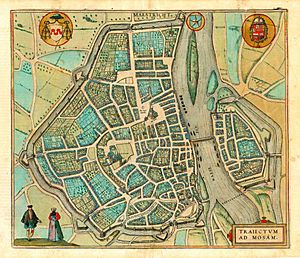

Siege of Maastricht (1579) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Siege of Maastricht |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Eighty Years' War | |||||||

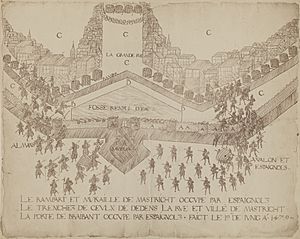

Spanish troops storming the city of Maastricht. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

Sebastien Tapin† |

|||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 1,200–2,000 | 20,000–34,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 900–1000 soldiers, plus 800-4,000 civilians | 4,000 | ||||||

The Siege of Maastricht was an important battle during the Eighty Years' War. This war was fought between the Netherlands and Spain. The siege lasted for many months, from March 12 to July 1, 1579. In the end, the Spanish army won the battle.

Contents

Why the Siege Happened

Trouble in the Netherlands

In the 1500s, the Netherlands was part of the Spanish Empire. But many people in the Netherlands were unhappy with Spanish rule. They especially disliked the Spanish king, Philip II, who was Catholic, because he tried to stop the spread of Protestantism.

This led to a big rebellion called the Eighty Years' War. The Spanish sent armies to control the region. But their harsh rules and high taxes made people even angrier. This caused more towns to join the rebellion.

Spain's New Leader

In 1578, Alexander Farnese became the new Spanish leader in the Netherlands. He was a very skilled military commander. He wanted to bring the rebellious provinces back under Spanish control.

Farnese knew that controlling Maastricht was very important. The city was a key location to stop help from reaching the rebels from Germany. It also helped ensure the local Prince-bishop of Liège would cooperate with Spain.

Divided Rebels

At this time, the rebels in the Netherlands were not fully united. Some provinces, mostly in the south, were Catholic and wanted peace with Spain. They formed the Union of Arras. Other provinces, mostly in the north, were Protestant and wanted more freedom. They formed the Union of Utrecht. This division made it easier for Farnese to plan his attack on Maastricht.

Before the siege, Farnese offered Maastricht a chance to surrender peacefully. He said he would protect their rights if they allowed Spanish soldiers inside. But the city leaders refused his offer.

The Siege of Maastricht Begins

Preparing for Battle

Maastricht was a large city with about 15,000 to 17,500 people. Its economy relied on textile factories and breweries. The city had been preparing for a siege since late 1578.

The city's governor, Melchior von Schwarzenberg, was in charge of the defense. But the main person organizing the defense was a military engineer named Sebastien Tapin. He was known for his amazing skills in building defenses. Tapin had thousands of men and women, including nuns, work to repair and strengthen the city walls. They built new defenses like ravelins (outer fortifications) and deepened the city moat. They also dug tunnels under the walls.

The city's defenders included about 1,200 soldiers (French, Scottish, and English) and around 6,000 armed citizens.

On the Spanish side, Farnese gathered a huge army of about 25,000 infantry and 8,000 cavalry. He brought 48 cannons and a lot of gunpowder. The Spanish army set up camps around the city. They built two pontoon bridges across the Meuse River to connect their forces on both sides.

First Attacks

The Spanish army began building forts around Maastricht to block any help from reaching the city. Farnese himself helped with the digging to inspire his soldiers.

Farnese and his engineers decided to attack the Tongeren gate, which they thought was a good spot. On March 23, the Spanish tried to storm a ravelin (an outer defense) in front of the Tongeren gate. They bombarded it with cannons. Spanish soldiers managed to get inside the ravelin, but the defenders fought back fiercely with cannons and muskets from the city walls. The Spanish were forced to retreat.

Underground Warfare

After the first attack failed, Farnese ordered more cannons to fire at the city walls. He also started a new tactic: digging mines under the walls. This led to a lot of underground fighting. Both sides dug tunnels, trying to blow up each other's defenses or intercept their tunnels.

The Dutch defenders were very clever. In one instance, they poured boiling water into a Spanish tunnel. In another, they used bellows from a church organ to blow smoke into a Spanish mine. The Spanish had to fight hard to reclaim their tunnels.

On March 31, the defenders launched a surprise attack from the city. They caught the Spanish soldiers off guard, many of whom were eating. The Dutch destroyed part of the Spanish trenches before retreating. This made Farnese very angry.

Second Major Attack

The defenders continued to make small attacks to disrupt the Spanish work. On April 8, Farnese ordered a big assault. He had learned that the Dutch were expecting help by April 15, so he wanted to capture the city quickly.

One mine was blown up under the ravelin at the Tongeren gate, damaging it. Spanish soldiers then attacked and captured the ravelin after a tough fight. However, the Dutch had built a second defense behind it.

On April 9, the Spanish launched a massive attack on two main gates: the Boschpoort and the Tongeren gate. They used many cannons to blast holes in the walls. The fighting was intense. The Dutch defenders threw boiling water, stones, and even carts with blades at the attackers.

The Spanish suffered heavy losses. About 700 Spanish soldiers were killed in this assault alone. Farnese reported that by April 9, 400 Spanish soldiers had died, and many more were wounded.

The Siege Continues

After the failed attack, Farnese decided to build a huge artillery platform near the Brussels gate. This platform was very tall, about 40 meters high, and allowed the Spanish to fire down into the city.

The Spanish also built a strong line of fortifications around the entire city. This was to completely cut off Maastricht and prevent any relief forces from reaching it. Farnese even hired 3,000 coal miners from Liège to help with the digging.

Inside Maastricht, the situation became desperate. Food was rationed, and the city minted its own emergency coins. People were forced to sell their grain. The defenders were exhausted.

The Spanish focused their attack on the Brussels gate. They used their tall artillery platform to make it hard for the Dutch to defend. Tapin, the main defender, was wounded but continued to direct the defense from a stretcher. By June 15, 14 Spanish cannons were firing at the new defenses.

On June 24, the Spanish tried to storm the defenses again, but they were pushed back with heavy losses. Tapin ordered a new trench to be dug behind the damaged walls. The defenders, including women who brought them food, stayed at their posts day and night.

The Fall of Maastricht

Final Attack and Capture

On June 26, Farnese offered the city a chance to surrender peacefully, but the defenders refused. So, he planned a final assault for June 29. The night before, Spanish and German soldiers tried a sneak attack, but it failed.

At dawn on June 29, the Spanish army launched its final, massive attack. The defenders were caught by surprise and could not hold their ground. They broke ranks and fled. Spanish, German, and Walloon soldiers chased them through the streets. Many people tried to hide in cellars, but they were found. Soldiers and civilians died in the fighting or drowned trying to escape in the Meuse River.

A final stand took place in the Vrijthof square, but the Spanish broke through. The remaining defenders, led by Tapin, tried to escape to Wyck by partially destroying the bridge.

About 4,000 people were captured and forced to pay a ransom. Their homes were looted. The total value of the stolen goods was said to be over 1 million gold coins. Farnese was ill during this time, which meant he couldn't fully control his soldiers, leading to more chaos.

The End for the Defenders

The Spanish attacked Wyck, where Tapin and the remaining defenders were. Tapin realized their situation was hopeless and surrendered. He asked for his and his soldiers' lives to be spared in exchange for a ransom.

Governor Schwarzenberg was killed during the battle. Captain Manzano, a Spanish defector who had helped Tapin, was captured. He was executed as a warning to others who might betray Spain.

Tapin was badly wounded. While some stories say he was spared by Farnese and later died from his wounds, it seems more likely that he was killed by angry Spanish soldiers. Farnese was very upset when he found out, as he would have preferred to save such a brave enemy.

Aftermath and Legacy

Maastricht's Recovery

The four-month siege and the capture of Maastricht left the city damaged. Some reports said that only a few hundred citizens remained, and the city had to be repopulated. However, later studies showed that Maastricht quickly recovered. While many people died from fighting and disease, and some wealthy residents left, the city's population bounced back. Many of the same leaders and workers continued their jobs after the siege.

The Spanish army also suffered many losses. Over 1,500 Spanish soldiers died, along with many German and Walloon soldiers.

Farnese, despite his illness, recovered and celebrated his victory. He stayed in Maastricht for eight months before continuing his military campaigns.

Political Impact

The capture of Maastricht was a huge victory for Spain. It helped Farnese in his negotiations with the southern Catholic provinces, which agreed to rejoin Spain. This further divided the rebels.

Philip II, the King of Spain, felt confident after this victory. He demanded that only the Catholic religion be allowed in the Netherlands. This led to the peace talks failing. In 1580, Philip outlawed William of Orange, a key rebel leader. In response, the northern provinces declared their independence from Spain in 1581. This officially created the Dutch Republic.

Art and History

The Siege of Maastricht was such an important event that it was shown in many paintings, engravings, and plays.

- Paintings: Two series of paintings were made for the Spanish king to celebrate the victory. These paintings showed the Spanish attacking Maastricht.

- Engravings: Early engravings by Frans Hogenberg showed both the siege and the capture of the city, including the violence. These images helped to gain support for the Dutch Revolt. Later, other artists like Jan Luyken and Romeyn de Hooghe also created engravings of the siege, often focusing on the dramatic events.

- South American Art: Even in the 18th century, paintings about Farnese's campaigns, including the Siege of Maastricht, were created in Spanish colonies in South America. These artworks helped to show the power of the Spanish monarchy.

See also

In Spanish: Sitio de Maastricht (1579) para niños

In Spanish: Sitio de Maastricht (1579) para niños

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |