Louis Antoine de Saint-Just facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Louis Antoine de Saint-Just

|

|

|---|---|

Saint-Just by Prud'hon, 1793 (Museum of Fine Arts of Lyon)

|

|

| Member of the National Convention | |

| In office 20 September 1792 – 27 July 1794 |

|

| Constituency | Aisne |

| 36th President of the National Convention | |

| In office 19 February 1794 – 6 March 1794 |

|

| Preceded by | Joseph-Nicolas Barbeau du Barran |

| Succeeded by | Philippe Rühl |

| Member of the Committee of Public Safety | |

| In office 30 May 1793 – 27 July 1794 |

|

| Personal details | |

| Born | 25 August 1767 Decize, Kingdom of France |

| Died | 28 July 1794 (aged 26) Paris, First French Republic |

| Political party | The Mountain |

| Signature | |

Louis Antoine Léon de Saint-Just (25 August 1767 – 28 July 1794) was an important figure in the French Revolution. He was a French revolutionary, a political thinker, and a leader of the Jacobin club. He was also a member and president of the National Convention, which was France's governing assembly.

Saint-Just was a close friend and trusted helper of Maximilien Robespierre. He played a big part during the time when the Jacobins were in charge (1793–1794) in the French First Republic. He worked as a lawmaker and a military leader. He became known for his role in the Reign of Terror, a period when the government used strong measures against those it saw as enemies. He often gave speeches that called for punishment for people who opposed the government. He also oversaw the arrests of many famous figures from the Revolution, some of whom were executed by guillotine.

From the start of the Revolution in 1789, young Saint-Just was very excited and wanted to be a leader. He quickly became a commander in his local National Guard. In August 1792, as soon as he turned 25, he was elected as a deputy to the National Convention in Paris. Even though he was young and new, Saint-Just bravely spoke out against King Louis XVI. He led the effort to have the King executed, which was successful. This bold action made him politically recognized and earned him the lasting support of Robespierre. Saint-Just joined Robespierre on the Committee of Public Safety and served for two weeks as President of the Convention. He also helped write important Jacobin laws, like the Ventôse Decrees and the Constitution of 1793.

Saint-Just was sent to oversee the army during the French Revolutionary Wars. He made sure the soldiers followed strict rules. At the same time, he worked to protect the troops under the new anti-aristocratic rules of the Revolution. Many people gave him credit for helping the army become stronger. His success as an overseer led to two more trips to the front lines, including his praised involvement in the important Battle of Fleurus.

Through all his work, Saint-Just stayed loyal to his role as a defender of the Committee of Public Safety. He publicly accused those who opposed the Jacobin government of being plotters and traitors. He was very strict in using force against them. He helped bring about the trials of the centrist deputy Jacques Pierre Brissot and his Girondins allies. He also targeted the extremist leader Jacques Hébert and his supporters, and his former colleague Georges Danton and other Jacobin critics. As more and more people were arrested and executed, opponents finally took action. Saint-Just and Robespierre were arrested in a sudden change of power on 27 July 1794. They were executed the next day, along with many of their supporters. In many histories of the Revolution, their deaths marked the end of the Reign of Terror.

Contents

Early Life and Beginnings in Politics

Louis Antoine de Saint-Just was born in Decize, France, in 1767. He was the oldest of three children. His father was a retired cavalry officer. In 1776, his family moved to Blérancourt. A year later, his father died. His mother worked hard to pay for his education. He went to school in Soissons and graduated in 1786.

As a young man, Saint-Just was known for being lively and rebellious. He showed interest in a young woman named Thérèse Gellé. When she married someone else, Saint-Just left home for Paris without telling anyone. His mother had him sent to a reformatory for several months. After this, he tried studying law at Reims University but eventually returned home without a job.

Early Writings and Revolutionary Ideas

Even when he was young, Saint-Just loved literature. He wrote a play and a long poem called Organt. He published Organt in 1789, just as the Revolution was starting. The poem was a fantasy story that praised simple, independent people. It also criticized the monarchy, the nobility, and the Church.

As the Revolution grew, Saint-Just changed his writing style. He started writing serious essays about politics and society. He wanted to become a leader in the Revolution.

Joining the Revolution

The Revolution quickly changed the power structure in Blérancourt. In 1790, the town held its first open elections. Saint-Just's friends became important leaders, including his brother-in-law, who became head of the local National Guard. Even though Saint-Just was too young and didn't meet the tax requirements, he was allowed to join the Guard.

He quickly showed his strict discipline. Within months, he became a commanding officer. He inspired people at local meetings with his strong patriotism. He also started writing to important revolutionary leaders like Camille Desmoulins and Maximilien Robespierre. In his first letter to Robespierre, he expressed great admiration.

The Spirit of the Revolution

While waiting for the next election, Saint-Just wrote a book called L'Esprit de la Revolution et de la constitution de France (The Spirit of the Revolution and the Constitution of France). It was published in 1791. In this book, he wrote about political ideas, influenced by thinkers like Montesquieu. He believed that government was necessary for society to succeed.

However, just days after his book was published, King Louis XVI tried to flee France. This event made Saint-Just's ideas about constitutional monarchy seem outdated. Public anger against the King grew. On 10 August 1792, a mob attacked the Tuileries Palace. In response, the Assembly called for a new election, allowing all men to vote. This was perfect timing for Saint-Just, who turned 25 that month. He was elected as a deputy for the Aisne region and went to Paris to join the National Convention. He was the youngest of its 749 members.

Becoming a Deputy

As a new deputy, Saint-Just was quiet at first. He joined the Parisian Jacobin Club but stayed away from other groups. He gave his first speech to the Convention on 13 November 1792, and it was very impactful. He spoke about what should happen to the King. Saint-Just strongly argued that "Louis Capet" (the King's family name) should be judged as a traitor and an enemy, deserving death. He said, "This man must reign or die!"

His speech greatly impressed the Convention. Robespierre was especially moved and spoke the next day with similar ideas. Their views became the official stance of the Jacobins. By December, the King was put on trial, sentenced to death, and executed by guillotine on 21 January 1793.

On 29 May 1793, Saint-Just was added to the powerful Committee of Public Safety.

Creating the Constitution of 1793

The first French Constitution, written in 1791, included a role for the king, so it was no longer valid. A new constitution was needed for the Republic. Saint-Just submitted his own detailed proposal in April 1793. His ideas included the right to vote, the right to ask the government for things, and equal chances for jobs. He strongly supported a simple "one man one vote" system for elections. This respect for old Roman and Greek traditions made him more popular.

Since no single plan got enough votes, a small group of deputies was chosen to write the official constitution. Saint-Just was one of the five members elected. Because their task was so important, they were all added to the new and powerful Committee of Public Safety.

The Committee had been given special powers to protect the country during the French Revolutionary War. Saint-Just took charge of writing the French Constitution of 1793. The new document was finished, presented to the Convention, and approved on 24 June 1793.

However, this new constitution was never actually put into practice. Because of the war, emergency measures were in place. These measures gave supreme power to the Convention, with the Committee of Public Safety at the top. Robespierre, with Saint-Just's help, worked hard to keep the government under these emergency "revolutionary" measures until the war was won.

Arrest of the Girondins

While Saint-Just was working on the constitution, there was a lot of political conflict. The sans-culottes (common people), represented by the Paris Commune, became very opposed to the moderate Girondins. On 2 June 1793, they surrounded the Convention and arrested the Girondin deputies. The other deputies, even the Montagnards who usually supported the sans-culottes, didn't like this action but felt they had to allow it.

The Girondin leader, Jacques Pierre Brissot, was accused of treason. Other Girondins were imprisoned. Saint-Just, who had been quiet about the Girondins before, now clearly supported Robespierre, who had long opposed them. Saint-Just delivered the Committee's report to the Convention, which led to their trials.

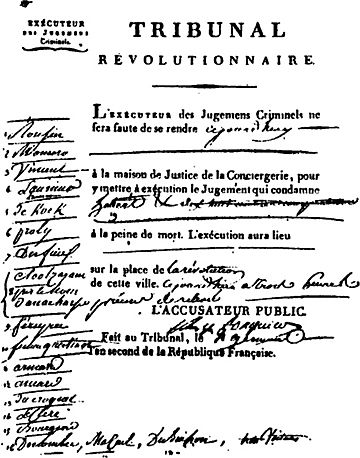

Some Girondins fled and tried to start a rebellion, which made the Committee's opinion harden. In July, Saint-Just gave a strong report to the Convention, saying there was no room for compromise. He insisted that the Girondins' trials must go forward and that the punishments must be severe. Brissot and twenty of his allies were eventually found guilty and executed by guillotine on 31 October 1793. Saint-Just used this situation to get approval for new, stricter laws, like the Law of Suspects (17 September 1793). This law gave the Committee much greater power to arrest and punish people.

Military Leader

On 10 October 1793, the Convention declared the Committee of Public Safety to be the supreme "Revolutionary Government." Saint-Just suggested that deputies from the Convention should directly oversee all military efforts, which was approved. As conditions at the war front worsened, Saint-Just was sent to the important Alsace region to help the Army of the Rhine. He went with Philippe-François-Joseph Le Bas and had "extraordinary powers" to enforce discipline and reorganize the troops.

| " Soldiers, we have come to avenge you, and to give you leaders who will marshal you to victory. We have resolved to seek out, to reward, and to promote the deserving; and to track down all the guilty, whoever they may be... All commanders, officers, and agents of the government are hereby ordered to satisfy within three days the just grievances of the soldiers. After that interval we will ourselves hear any complaints, and we will offer such examples of justice and severity as the Army has not yet witnessed." |

| – Saint-Just's first message to the Army of the Rhine, 1793 |

Saint-Just was very strict. He demanded results from commanders and listened to the complaints of common soldiers. He quickly put the entire army under very harsh discipline. Many officers were dismissed, and some were executed.

Saint-Just also dealt with opponents of the Revolution among soldiers and civilians. He arrested Eulogius Schneider, a powerful leader in Strasbourg, and took equipment for the army. He worked closely with General Charles Pichegru. Under Saint-Just's close watch, Pichegru and General Lazare Hoche successfully defended the border and began an invasion of the German Rhineland.

After revitalizing the army, Saint-Just returned to Paris, where his success was praised. However, he was quickly sent back to the front lines in Belgium, where the Army of the North faced similar problems. In early 1794, he again brought results effectively. But his mission was cut short because Robespierre needed his help in Paris.

President of the Convention

With the French army doing well and the Girondins removed, the left-wing Montagnards, led by the Jacobins and Robespierre, controlled the Convention. On 19 February 1794, Saint-Just was elected President of the National Convention for two weeks.

With this new power, he convinced the Convention to pass the Ventôse Decrees. These radical laws would take property from wealthy families who had left France and give it to needy commoners (sans-culottes). However, these laws, which aimed to redistribute wealth, were never fully put into action. The Committee struggled to create ways to enforce them, and fast-moving political events left them behind.

Saint-Just strongly supported these decrees. He argued that they would help create a new era. He said, "Eliminate the poverty that dishonors a free state; the property of patriots is sacred but the goods of conspirators are there for the wretched."

Arrest of the Hébertists

By spring 1794, the Committee of Public Safety, led by Robespierre, Saint-Just, and Georges Couthon, had almost complete control. However, they still had rivals. One big problem was Jacques Hébert, a popular speaker who criticized the Jacobins in his newspaper. His extreme followers, called Hébertists, even called for a rebellion.

Saint-Just, as president of the Convention, clearly stated that anyone who attacked the revolutionary government should be executed. The Convention agreed on 3 March 1794. Robespierre joined Saint-Just in criticizing Hébert. Hébert and his closest friends were arrested the next day. A week later, Saint-Just told the Convention that the Hébertists were part of a foreign plot against the government. The accused were sent to the Revolutionary Tribunal. Saint-Just declared, "No more pity, no weakness towards the guilty... Henceforth the government will pardon no more crimes." On 24 March 1794, the Tribunal sent Hébert and most other important Hébertists to the guillotine.

Arrest of the Dantonists

The political conflict, known as the Reign of Terror, continued to spread. After the Hébertists were removed, attention turned to the Indulgents, including Fabre d'Églantine and Robespierre's former friend Georges Danton. Danton was a strong voice among those who opposed the Committee's extreme measures. He especially disagreed with Saint-Just's strictness and use of violence. On 30 March, the committees decided to arrest Danton and his allies. On 31 March, Saint-Just publicly attacked them.

Danton's criticism of the Terror gained him some support. However, a financial scandal involving the French East India Company provided a reason for his downfall. Robespierre again sent Saint-Just to the Convention to deliver a report (31 March 1794) announcing the arrest of Danton and "the last supporters of royalism." Saint-Just accused Danton of corruption and of plotting to bring back the monarchy. He called him a "bad citizen" and a "wicked man." After a quick trial, Danton, Camille Desmoulins, and other supporters were executed on 5 April 1794. Saint-Just had promised this would be a "final cleansing" of the Republic's enemies. However, there is some evidence that Saint-Just was becoming uneasy, privately writing that "The Revolution is frozen; all principles are weakened."

The removal of the Hébertists and Dantonists created a false sense of stability. Their deaths caused deep anger in the Convention. It also made it harder for the Jacobins to control the unpredictable common people. This loss of popular support would be disastrous for Saint-Just, Robespierre, and other Jacobins later on.

As the person who delivered the Committee's reports, Saint-Just became the public face of the Terror. After April 1794, the three main leaders (Robespierre, Saint-Just, and Couthon) increased their control over the state's security. Saint-Just created a new "general police" bureau for the Committee of Public Safety, which took over powers from another committee. Soon after, Robespierre took over this new bureau when Saint-Just left Paris for the war front again.

Final Days

The French army was still fighting, and Saint-Just was sent back to Belgium to help prepare for battle. From April to June 1794, he again oversaw the Army of the North and helped achieve victory at Fleurus. In this tough battle on 26 June 1794, Saint-Just used his strictest rules, ordering any French soldiers who turned away from the enemy to be shot immediately. He felt justified when the victory forced the Austrians to retreat from the Southern Netherlands. Fleurus was a turning point in the War of the First Coalition, with France remaining on the offensive. After returning from the battle, Saint-Just was seen as a hero.

Back in Paris, Saint-Just found that Robespierre's political position had weakened a lot. As the Terror reached its peak, the danger of a counter-attack from their enemies became very high. Opponents of the Terror argued that the war was going well, so the strict measures of the Terror were no longer needed.

With political conflict at a high point, the Committee introduced a new version of the "Law of Suspects," called the Law of 22 Prairial. This law created a new category of "enemies of the people" with very vague definitions, meaning almost anyone could be accused. Accused people were not allowed to have lawyers, and the Revolutionary Tribunal was told to only give death sentences. Robespierre quickly pushed this law through. Although Saint-Just was not directly involved in writing it, he likely supported it. This law greatly expanded the Tribunal's power and led to the "Great Terror," where the number of executions in Paris increased significantly.

The Law of Prairial was the breaking point for opponents of the Committee. Resistance to the Terror spread throughout the Convention. Saint-Just tried to address the divisions. He declared that he was willing to make some compromises. However, some of his opponents, known as Thermidorians, later claimed he was trying to give Robespierre dictatorial power. Their attitude towards Saint-Just changed when he gave a strong public defense of Robespierre on 27 July 1794.

Thermidor

At noon, Saint-Just went to the Convention, ready to blame his opponents. He began by saying, "I am from no faction; I will contend against them all." However, he was interrupted and accused of not keeping a promise to show his speech beforehand. As accusations piled up, Saint-Just remained silent. He was accused of forming a group with Robespierre and Couthon, like the ancient Roman triumvirates. Several deputies physically pushed him away from the speaker's stand.

Saint-Just kept his dignity but lost his life. Robespierre tried to speak in his support but struggled. His brother Augustin and other allies also tried to help, but failed. The meeting ended with an order for their arrest. Saint-Just was taken to prison. However, he and four others were invited to take refuge at the Hôtel de Ville by the mayor. Around 2 a.m., soldiers broke in. Saint-Just calmly gave himself up. He, Robespierre, and twenty of their associates were guillotined the next day. Saint-Just reportedly faced his death with calmness and pride. As a final act of identification, he pointed to a copy of the Constitution of 1793 and said, "I am the one who made that." Saint-Just and those executed with him were buried in the Errancis Cemetery. Later, their remains were moved to the Catacombs of Paris.

Legacy and Character

Other Writings

Throughout his political career, Saint-Just continued to work on books and essays about the meaning of the Revolution. These writings were collected after his death. They include his early poem Organt, his play Arlequin Diogène, and his book L'Esprit de la Revolution, along with his public speeches, military orders, and private letters.

Many of Saint-Just's ideas for laws were put together after his death in a book called Fragments sur les institutions républicaines. These ideas were even more radical than the Constitution of 1793. They were inspired by the strict traditions of ancient Sparta. Many of his proposals are seen as early socialist ideas. The main theme was equality, which Saint-Just summarized as: "Man must be independent... There should be neither rich nor poor."

Saint-Just's Personality

Saint-Just was ambitious and always working hard towards his goals. He once said, "For Revolutionists there is no rest but in the tomb." People at the time often described him as arrogant, believing he was a skilled leader and had the right revolutionary spirit. Critics said he thought he was superior and that his will was law.

As Saint-Just became more important, his personality changed. From being lively and passionate in his youth, he became very focused, "tyrannical and pitilessly thorough." He became known as "the ice-cold ideologist of republican purity," someone who was "as inaccessible as stone to all the warm passions."

In his public speeches, Saint-Just was even more daring than Robespierre. About France's internal problems, he said, "You have to punish not only the traitors, but even those who are indifferent; you have to punish whoever is passive in the republic, and who does nothing for it." He believed the only way to create a true republic was to remove all its enemies.

Despite his flaws, Saint-Just is often respected for how strongly he believed in his ideas. Even though his words and actions might seem harsh, his commitment to them is rarely questioned. Like Robespierre, he was seen as incorruptible because he wasn't interested in money or personal gain, but only in advancing his political goals.

See also

In Spanish: Louis de Saint-Just para niños

In Spanish: Louis de Saint-Just para niños

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |