Jacques Hébert facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Jacques Hébert

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Jacques René Hébert

15 November 1757 Alençon, Kingdom of France |

| Died | 24 March 1794 (aged 36) Paris, French First Republic |

| Cause of death | Execution by guillotine |

| Political party | The Mountain (1792–1794) |

| Other political affiliations |

Jacobin Club (1789–1792) Cordeliers Club (1792–1794) |

| Spouse |

Marie Marguerite Françoise Hébert

(m. 1792) |

| Children | Virginie-Scipion Hébert (1793–1830) |

| Parents | Jacques Hébert (?–1766) and Marguerite La Beunaiche de Houdré (1727–1787) |

| Residences | Paris, France |

| Occupation | Journalist, writer, publisher, politician |

| Signature |  |

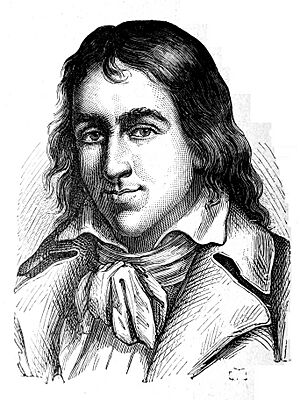

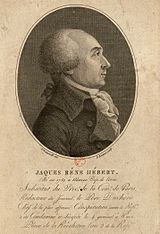

Jacques René Hébert (born November 15, 1757 – died March 24, 1794) was a French journalist during the French Revolution. He started and edited a very popular newspaper called Le Père Duchesne. This newspaper shared strong, radical ideas.

Hébert became an important leader in the French Revolution. He had many followers who were known as the Hébertists. People sometimes called him Père Duchesne after his famous newspaper.

Contents

Jacques Hébert's Early Life

Jacques René Hébert was born in Alençon, France, on November 15, 1757. His father was a goldsmith and a former judge.

Hébert studied law and worked as a clerk. After some financial difficulties, he moved to Rouen and then to Paris. For a while, he struggled to make a living. He found work in a theater, where he tried writing plays, but they were never performed.

In 1789, he began writing pamphlets. These were small booklets that shared his ideas. In 1790, one of his pamphlets gained attention. He then became a key member of the Cordeliers political club in 1791.

Le Père Duchesne Newspaper

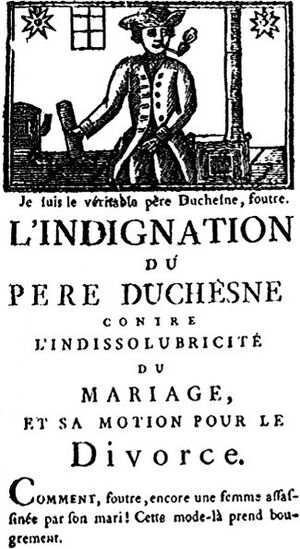

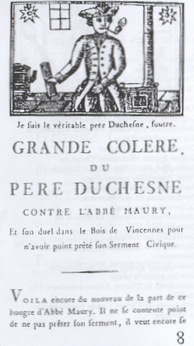

From 1790 until his death, Hébert became a strong voice for the working people of Paris. He did this through his very popular and important newspaper, Le Père Duchesne.

In his newspaper, Hébert wrote as a character named Père Duchesne. This character was a patriotic sans-culotte, which meant he was a common person who supported the revolution. Père Duchesne would tell made-up stories about talking with the French king or government officials.

Hébert and his followers, the Hébertists, believed that many more aristocrats should be investigated and removed. They thought that France could only truly become a new, free country by getting rid of the old noble class. In his newspaper, Hébert called aristocrats "enemies of the constitution." He believed they were "conspiring against the nation."

Much of Hébert's fame came from his strong criticism of King Louis XVI in his newspaper. These stories used strong, direct language. They were also clever and connected deeply with the poorer people of Paris. Street sellers would shout: "Father Duchesne is very angry today!"

Hébert did not create the character of Père Duchesne. However, his use of the character helped turn Père Duchesne into a symbol for the sans-culottes. Père Duchesne was shown as an older man, smoking a pipe and wearing a Phrygian cap. This cap was a symbol of freedom.

Hébert's writing style and the way he dressed matched his readers. This made them listen to and follow his message. A French historian called Hébert "The Homer of filth." This meant he was skilled at using everyday language to reach a wide audience.

Hébert's newspaper became very popular. The Paris Commune, which was the city government of Paris, bought many copies of his paper. They gave them out for free to the public and to soldiers. This helped Le Père Duchesne become the best-selling paper in Paris, especially after the death of another popular journalist, Jean-Paul Marat, in 1793.

Hébert's Views on the Monarchy

Between 1790 and 1793, Hébert's newspaper often talked about the expensive lifestyle of the monarchy. At first, from 1790 to 1792, Le Père Duchesne supported a constitutional monarchy. This meant a king who ruled with a constitution. He even supported King Louis XVI and the Marquis de La Fayette.

However, he was always very critical of Queen Marie Antoinette. She was an easy target for criticism after the Affair of the Diamond Necklace. Hébert often blamed her lavish spending for France's problems. He suggested that if she changed her ways, the monarchy could be saved. But he doubted she would change. He often called her "Madame Veto," a nickname that showed her unpopularity.

After the king's failed attempt to escape Paris, known as the flight to Varennes, Hébert's tone became much harsher. He no longer supported the monarchy.

In his newspaper, Hébert used the fictional character of Père Duchesne to share his message. This character was strong and outspoken, showing great anger and happiness. He was not afraid to express his feelings using direct and sometimes harsh words.

Role in the Revolution

Hébert agreed with many ideas of the radical Montagnard group. However, he was not officially a member of this group.

On July 17, 1791, Hébert was at the Champ de Mars to sign a petition asking for King Louis XVI to be removed. He was caught up in the Champ de Mars Massacre, where troops fired on the crowd. This event made him even more committed to the revolution. His newspaper then began to attack figures like Lafayette and Mirabeau.

Hébert married Marie Goupil in February 1792. She was a former nun. They had a daughter named Virginie-Scipion Hébert. During this time, Hébert lived a comfortable life. He hosted important people like Jean-Nicolas Pache, the mayor of Paris.

As a member of the Cordeliers club, he was part of the revolutionary Paris Commune. He supported strong actions against those seen as enemies of the revolution, including the September Massacres. In December 1792, he was appointed to a role in the commune. He also supported attacks against the Girondin group, another political faction.

In February 1793, he voted against the Maximum Price Act, which would have set a price limit on grain. He believed it would cause problems. In May 1793, he was arrested by a special commission. However, with support from the sans-culottes, he was released just three days later.

Dechristianization Movement

Dechristianization was a movement during the French Revolution. Its supporters wanted to create a society that was not based on religion. They believed they needed to reject the old ways and the influence of the Catholic Church.

While some leaders, like Robespierre, believed people should have the right to religion, Hébert and his followers wanted to quickly and strongly remove religion from society. The writer and philosopher Voltaire influenced Hébert's views. Like Voltaire, Hébert thought that allowing different religious beliefs was important for society to move past old superstitions. He saw traditional religion as a barrier to this goal. Hébert even suggested that Jesus was not a demigod, but a good sans-culotte.

The dechristianization movement targeted Catholicism and other forms of Christianity. It involved removing clergy, closing churches, and destroying religious monuments. Public and private worship were outlawed.

On November 10, 1793, the Hébertists held the first Festival of Reason. This was a civic festival celebrating the goddess of Reason. It was moved to the Notre Dame Cathedral, which they renamed the "Temple of Reason."

Conflict with Robespierre and Execution

After successfully challenging the Girondins, Hébert continued to criticize those he saw as too moderate. This included important figures like Danton and Robespierre.

The government, with support from the Jacobins, decided to act against Hébert. On March 13, 1794, Hébert and other leaders of the Hébertists were arrested.

In the Revolutionary Tribunal, Hébert was accused of various wrongdoings. He was sentenced to death along with others. Their execution took place on March 24, 1794. He was put to death by guillotine. His body was buried in the Madeleine Cemetery. His wife was executed twenty days later, on April 13, 1794.

The execution of Hébert was a very important event in the revolution. Saint-Just, a leading Jacobin, said that after Hébert's execution, "the revolution is frozen." This showed how central Hébert and his followers were to the revolution's ongoing changes.

Hébert's Influence

It is hard to know exactly how much Hébert's newspaper, Le Père Duchesne, changed political events between 1790 and 1794. Historians believe that while newspapers could influence people's political views, they didn't necessarily create them. A person's social class, for example, also played a big role in their political decisions.

However, Hébert's writings certainly had a dramatic effect on his readers. His wide readership and strong voice throughout the Revolution made him a very important public figure. Le Père Duchesne clearly had a notable ability to influence the general population of France.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Jacques-René Hébert para niños

In Spanish: Jacques-René Hébert para niños

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |