Camille Desmoulins facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Camille Desmoulins

|

|

|---|---|

Portrait of Camille Desmoulins, c. 1790 (Musée Carnavalet)

|

|

| Deputy of the National Convention | |

| In office 20 September 1792 – 5 April 1794 |

|

| Constituency | Paris |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 2 March 1760 Guise, Picardy, France |

| Died | 5 April 1794 (aged 34) Place de la Révolution, Paris, France |

| Cause of death | Execution by guillotine |

| Political party | The Mountain |

| Other political affiliations |

Jacobin Club |

| Spouse |

Lucile Duplessis

(m. 1790) |

| Occupation | Journalist |

| Signature |  |

Lucie-Simplice-Camille-Benoît Desmoulins (born March 2, 1760 – died April 5, 1794) was a French journalist and politician. He played a key part in the French Revolution. He is famous for helping to start the events that led to the Storming of the Bastille.

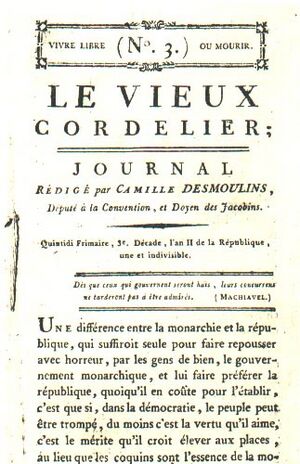

Desmoulins also wrote a newspaper called Le Vieux Cordelier. In it, he strongly criticized the Reign of Terror, a very violent period of the Revolution. He was a school friend of Maximilien Robespierre and a close friend and ally of Georges Danton. Both Robespierre and Danton were important leaders in the French Revolution.

Camille Desmoulins was trained as a lawyer. He was very excited about the Revolution from the very beginning. On July 12, 1789, he gave a powerful speech. This speech encouraged people to take action. It led to widespread unrest in Paris. Two days later, this unrest resulted in the Storming of the Bastille.

After this, Desmoulins became a well-known writer of pamphlets. He openly supported a republic (a country without a king). He also believed in using revolutionary violence. He attacked the old French system (the Ancien Régime). He also criticized other revolutionary leaders. His writings helped to bring down the moderate Girondist group. This then led to the start of the Reign of Terror.

During the Reign of Terror, Desmoulins and his friend Georges Danton grew apart from Robespierre. Desmoulins used his newspaper, Le Vieux Cordelier, to criticize the extreme violence of the government. He asked for mercy for those accused. This angered Robespierre. In April 1794, Desmoulins was sentenced to death. He was executed by guillotine along with Danton.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Camille Desmoulins was born in Guise, a town in northern France. His father, Jean Benoît Nicolas Desmoulins, was a local official. His mother was Marie-Madeleine Godart. When Camille was fourteen, his father helped him get a scholarship. This allowed him to attend the Lycée Louis-le-Grand school in Paris.

Desmoulins was a very good student. He studied classical literature and politics. He especially liked the writings of ancient Roman thinkers like Cicero and Tacitus. Some of his classmates included Maximilien Robespierre and Louis-Marie Stanislas Fréron.

After school, Desmoulins became a lawyer in Paris in 1785. However, he had a stammer (a speech difficulty). He also didn't have many important connections in the legal world. These challenges made it hard for him to succeed as a lawyer. So, he decided to become a writer instead. His interest in public affairs led him to become a political journalist.

In March 1789, Desmoulins' father was chosen to be a representative. He was supposed to go to the Estates-General of 1789, a big meeting in France. But he was too sick to go. Camille Desmoulins watched the procession of the Estates-General on May 5, 1789. He then wrote a poem about it called Ode aux Etats Generaux. A powerful politician named Honoré Gabriel Riqueti, comte de Mirabeau hired Desmoulins to write for his newspaper. This helped Desmoulins become more known as a journalist.

Starting the Revolution

Life was hard for Desmoulins in Paris. He was often poor because his law career didn't take off. But he was very excited by the political changes happening. These changes were sparked by the summoning of the Estates-General.

He wrote letters to his father about the events. He described the representatives entering the Palace of Versailles. He also criticized how the meeting hall was closed to the deputies. These deputies had declared themselves the National Assembly. This led to the famous Tennis Court Oath.

On July 11, 1789, King Louis XVI fired his popular finance minister, Jacques Necker. This news sparked Desmoulins' rise to fame. On July 12, Desmoulins jumped onto a table outside the Cafe de Foy. This cafe was in the garden of the Palais Royal, a place where many political thinkers met. He gave a passionate speech to the crowd.

Despite his usual stammer, he spoke clearly and powerfully. He urged the crowd to "take up arms and adopt cockades." These were special ribbons to identify each other. He said Necker's dismissal was a warning sign. Desmoulins and other revolutionaries believed a massacre of those who disagreed with the king was coming. The crowd believed him and quickly joined him. Riots spread quickly throughout Paris.

The ribbons worn by the crowd were first green. Green was a color of hope. But green was also linked to the King's brother, the Comte d'Artois. So, the ribbons were quickly changed. They became red and blue, the traditional colors of Paris. On July 14, the people of Paris attacked the Hôtel des Invalides to get weapons. Desmoulins was among them. He armed himself with a rifle and two pistols. This led to the Storming of the Bastille.

Writing for Change

In June 1789, Desmoulins wrote a strong pamphlet called La France Libre. Parisian publishers didn't want to print it at first. But after the Storming of the Bastille and Desmoulins' part in it, things changed. On July 18, Desmoulins' work was finally published.

His pamphlet was very advanced for its time. Desmoulins clearly called for a republic. He wrote that "popular and democratic government is the only constitution which suits France." La France Libre also criticized the role of kings, nobles, and the Catholic clergy.

Desmoulins became even more famous as a radical writer. In September 1789, he published Discours de la lanterne aux Parisiens. The title referred to a lamppost in Paris. This lamppost was often used by rioters to hang people accused of being against the Revolution. A famous song, Ça ira, also mentions this lamppost. It says, "To the lantern with the aristocrats... The aristocrats, we'll hang them!"

The Discours de la lanterne celebrated political violence. It praised the citizens of Paris for their loyalty and patriotism. This strong message was popular in Paris. Because of this pamphlet, Desmoulins became known as the "Lanterne Prosecutor."

In September 1789, Desmoulins started a weekly newspaper. It was called Histoire des Révolutions de France et de Brabant. This paper combined news, revolutionary ideas, humor, and cultural comments. Desmoulins said it would cover "The universe and all its follies." The newspaper was very popular. Desmoulins was able to escape the poverty he had known in Paris.

The newspaper supported the Revolution and was against the king. It celebrated the passion of "patriots." It also criticized the unfairness of the old noble system. Desmoulins attacked those he disagreed with very harshly. This led to lawsuits and criticism. His friendships with powerful people like the Comte de Mirabeau were hurt. They were angry about what they saw as false statements.

When the Comte de Mirabeau died in April 1791, Desmoulins wrote a harsh attack. He called Mirabeau the "god of orators, liars, and thieves." This showed how Desmoulins could turn against former friends. He later did the same to other revolutionary figures like Jacques Pierre Brissot.

On July 16, 1791, Desmoulins led a group asking for King Louis XVI to be removed from power. The King had tried to flee Paris with his family in June. This caused unrest. The petition added to the tension. The next day, a large crowd gathered. Soldiers fired on them. This event became known as the Champs de Mars Massacre. After this, arrest warrants were issued for Desmoulins and Georges Danton. Danton left Paris. Desmoulins stayed but wrote less for a while.

In 1792, Desmoulins published a pamphlet called Jean Pierre Brissot démasqué. It strongly attacked Jean Pierre Brissot. Desmoulins accused Brissot of betraying the idea of a republic. This attack was later expanded in another work. This work accused the Girondist political group, which Brissot was part of, of being traitors. This contributed to the arrest and execution of many Girondist leaders in October 1793. Desmoulins felt great regret for his role in their deaths. He was heard to say, "O my God! my God! It is I who kill them!"

In the summer of 1793, General Arthur Dillon, a friend of Desmoulins, was put in prison. Desmoulins openly wrote a letter defending Dillon. In it, he also attacked powerful members of the Committee of Public Safety. These included Saint-Just and Billaud-Varenne.

Starting December 5, 1793, Desmoulins published his most famous newspaper: Le Vieux Cordelier. The title itself suggested a disagreement with the current government. It meant Desmoulins spoke for the "old" members of the Club des Cordeliers. This was against the more extreme groups now in power.

In its seven issues, Le Vieux Cordelier criticized the suspicion, cruelty, and fear of the Revolution. Desmoulins compared the Revolutionary Terror to the harsh rule of the Roman emperor Tiberius. He called for a "Committee of Clemency" (mercy) to stop the mercilessness. In the fourth issue, Desmoulins wrote directly to Robespierre. He said, "My dear Robespierre... my old school friend... Remember the lessons of history and philosophy: love is stronger, more lasting than fear." These calls for mercy were seen as against the Revolution. This led to Desmoulins being kicked out of the Cordeliers Club. He was also criticized by the Jacobins. Eventually, it led to his arrest and execution.

Political Role and Downfall

Desmoulins was active in the attack on the Tuileries Palace on August 10, 1792. This attack led to the end of the monarchy. Soon after, he became Secretary-General to Georges Danton, who was then the Justice Minister. On September 8, 1792, Desmoulins was elected as a representative for Paris. He joined the new National Convention. He was part of "The Mountain" group. He voted to create the Republic and to execute King Louis XVI. His political ideas were similar to Danton's and, at first, Robespierre's.

In late 1793, as the Terror grew, Desmoulins spoke less in the Convention. When he did speak, he was one of the few asking for mercy. On October 16, 1793, he asked for an exception for Dutch citizens. The Convention had ordered the arrest of all citizens from countries France was at war with. Desmoulins also helped create the first draft of the Civil Code.

Desmoulins also supported a measure in August 1793. This measure would have given spouses equal rights to manage property. He argued against the idea that men were "naturally superior." He called the old system, where women were legally under their husbands, "the creation of despotic governments." Later that month, Desmoulins supported no-fault divorce. He said divorce should be freely available if either person wanted it.

The first issue of Vieux Cordelier came out on December 5, 1793. It was dedicated to Robespierre and Danton. But it marked the beginning of a split between Desmoulins and Robespierre. The newspaper started by criticizing the extreme Hébertist group. Robespierre approved of this at first. But the journal quickly expanded its criticism to the Committee of Public Safety. Desmoulins asked Robespierre to make these groups more moderate. On December 20, Robespierre suggested a group to "examine all detentions and free the innocent." Desmoulins supported this. He called for a "committee of clemency" to end the Terror.

In Le Vieux Cordelier, especially the third and fourth issues, Desmoulins criticized the Terror. He argued for mercy for prisoners. He also demanded the return of freedom of the press. He wrote that "liberty has neither old age nor infancy; she has but one age, that of strength and vigour." He said that liberty is "happiness, reason, equality; she is justice." He asked to "Open the prisons of those two hundred thousand citizens whom you call 'suspects'." He argued that suspicion should not lead to prison.

Desmoulins used many arguments to support his ideas. He used historical examples, especially from Ancient Rome. He said, "You wish to exterminate all your enemies by the guillotine! But was there ever greater folly? Can you kill one person on the scaffold without making yourselves ten more enemies amongst his family and his friends?" He believed that mercy would help the Revolution. He said, "clemency is itself a Revolutionary measure, the most effective of all when it is wisely dealt out."

Desmoulins also strongly argued for renewed freedom of the press. He said that if freedom of the press existed, it alone could balance even a very strict government. He criticized the lack of press freedom in France. He asked, "Am I, a Frenchman, I, Camille Desmoulins, not as free as an English journalist?" He believed that only those against the Revolution would fear a free press.

In his fourth issue, Desmoulins spoke directly to Robespierre. He reminded him that "love is stronger, more enduring than fear." He said that leaders rise "on stairs of blood."

Desmoulins used practical arguments. He said that too much terror would make people hate the Revolution. This could lead to a backlash against it. He used ideas from Machiavelli's The Prince. He argued that generosity helps a ruler stay popular. But too much violence makes a ruler hated and overthrown.

Desmoulins criticized Jacques Hébert's calls for more terror. But he also opposed Hébert's arrest. In his last issue, he said he preferred the strong criticisms of the Hébertists. He preferred them over the "icy silence" of the Jacobins. He believed that strong debate was better than fear that "freezes thought."

Desmoulins also repeated his opposition to the war with Austria and its allies. He said that "war will always be the resource of despotism." He accused Robespierre of changing his mind on the war. Robespierre had originally been against it.

On January 7, 1794, the Jacobin Club tried to expel Desmoulins. Robespierre first tried to protect him. He suggested burning the offending issues of Le Vieux Cordelier. Desmoulins replied, "Burning is not answering." This echoed Jean-Jacques Rousseau, a philosopher important to Robespierre. Robespierre then called Desmoulins a "spoilt child." He said, "Well, since he wishes it, let him be covered in ignominy." Despite this, Desmoulins refused to give up his newspaper.

In his seventh issue, Desmoulins said that freedom of the press and the form of government were the basis of a republic. He believed these were more important than virtue. In this, he directly disagreed with Robespierre's views.

Meanwhile, Danton's secretary, Fabre d'Églantine, was caught in a financial scam. He was arrested for corruption. This scandal made Danton and his allies look bad. Robespierre then supported kicking Desmoulins out of the Jacobin club. After the Hébertists were executed in March 1794, the Montagnards focused on Danton's group. They accused Danton and Desmoulins of corruption and being against the Revolution. Arrest warrants for Desmoulins and others were issued on March 31.

Trial and Execution

Danton, Desmoulins, and others accused of being Danton's allies were tried. The trial lasted from April 3 to 5. It was more political than criminal. When asked his name and age, Desmoulins replied: "Benoît Camille Desmoulins, age of thirty-three – the age of Jesus, a critical age for patriots."

The accused were not allowed to defend themselves. This was due to a rule from the National Convention. The prosecutor, Antoine Quentin Fouquier-Tinville (Desmoulins' cousin), also threatened the jury. This helped ensure a guilty verdict. The accused were also denied witnesses to speak for them. Desmoulins had asked for Robespierre to be a witness. The verdict was given when the accused were not in the courtroom. This was to prevent unrest. Their execution was set for the same day.

From prison, Desmoulins wrote a letter to his wife. He said, "I have dreamed of a Republic such as all the world would have adored. I could never have believed that men could be so ferocious and so unjust."

As Desmoulins was taken to the execution cart, he learned of his wife's arrest. He became very distressed. Several men were needed to get him onto the cart. He struggled and tried to speak to the crowd. He ripped his shirt in the process. Lucile, his wife, was quickly found guilty of conspiracy. She was executed eight days later.

On April 5, 1794, fifteen people were guillotined together. This group included Desmoulins, Marie Jean Hérault de Séchelles, and Philippe Fabre d'Églantine. Desmoulins was the third to die. Danton was the last. Desmoulins and the others were buried in the Errancis Cemetery. This was a common burial place for those executed during the Revolution. Later, their remains were moved to the Catacombs of Paris.

Family Life

On December 29, 1790, Desmoulins married Lucile Duplessis. He had known her for many years. Lucile's father had not wanted them to marry. He thought a journalist's life could not support a family. Robespierre, Brissot, and Jérôme Pétion de Villeneuve were witnesses at the wedding. The wedding took place at the Saint-Sulpice Church in Paris.

Camille and Lucile had one child, Horace Camille. He was born on July 6, 1792.

Lucile Desmoulins was arrested just days after her husband. She was accused of trying to free him from prison. She was also accused of plotting against the Republic. She was executed on April 13, 1794. This was the same day as the widow of Jacques Hébert. In a last note to her mother, she wrote, "I shall go to sleep in the calm of innocence. Lucile."

Horace Camille Desmoulins was raised by Lucile's sister and mother. He later married Zoë Villefranche and had four children. The French government later gave him a pension (regular payment). He died in 1825 in Haiti.

See also

In Spanish: Camille Desmoulins para niños

In Spanish: Camille Desmoulins para niños

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |