Bertrand Barère facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Bertrand Barère

|

|

|---|---|

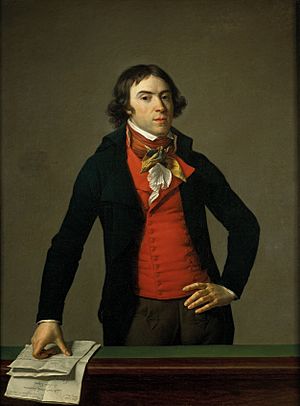

Portrait of Barère by Jean-Louis Laneuville (1794)

|

|

| Member of the Chamber of Representatives from Hautes-Pyrénées |

|

| In office 3 June 1815 – 13 July 1815 |

|

| Preceded by | Jean Lacrampe |

| Succeeded by | Jean-Baptiste Darrieux |

| Constituency | Tarbes |

| Member of the Council of Five Hundred from Hautes-Pyrénées |

|

| In office 22 October 1795 – 26 December 1799 |

|

| Preceded by | Himself in the National Convention |

| Constituency | Tarbes |

| Commissioner to Navy, Military and Foreign Affairs | |

| In office 6 April 1793 – 1 September 1794 |

|

| Majority | Committee of Public Safety |

| 6th President of the National Convention | |

| In office 29 November 1792 – 13 December 1792 |

|

| Preceded by | Henri Grégoire |

| Succeeded by | Jacques Defermon |

| Member of the National Convention from Hautes-Pyrénées |

|

| In office 4 September 1792 – 26 October 1795 |

|

| Preceded by | Jean Dareau-Laubadère |

| Succeeded by | Himself in the Council of Five Hundred |

| Constituency | Tarbes |

| Deputy to the Estates-General for the Third Estate |

|

| In office 5 May 1789 – 9 July 1789 |

|

| Constituency | Bigorre |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 10 September 1755 Tarbes, Gascony, France |

| Died | 13 January 1841 (aged 85) Tarbes, Hautes-Pyrénées, France |

| Political party | Marais (1792–1795) Montagnard (1795–1799) Liberal Left (1815) |

| Spouse |

Élisabeth de Monde

(m. 1785; separated 1793) |

| Profession | Lawyer |

| Signature |  |

Bertrand Barère de Vieuzac (born September 10, 1755 – died January 13, 1841) was an important French politician and journalist. He was a key member of the National Convention during the French Revolution.

Barère was part of a group called the Plain. This group was often influenced by a more extreme group known as the Montagnards. He helped create the Committee of Public Safety in April 1793. He also supported forming a special army in September 1793. Some people, like Francois Buzot, blamed Barère for the Reign of Terror, a time of great fear and violence.

In 1794, Barère turned against Maximilien Robespierre. He joined the effort to remove Robespierre from power.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Bertrand Barère was born in Tarbes, a town in the Gascony region of France. His full name, Barère de Vieuzac, came from a small piece of land his father owned. His father, Jean Barère, was a lawyer. His mother, Jeanne-Catherine Marrast, came from an old noble family.

Barère went to a local school as a child. Later, he attended college. In 1770, he started working as a lawyer in Parlement of Toulouse, a high court. He was quite successful as a lawyer.

He also enjoyed writing. He sent his writings to various writing clubs in southern France. In 1788, he became a member of the Academy of Floral Games in Toulouse. This academy held yearly events where they gave out gold and silver flowers for the best poems and speeches.

Barère won many awards from the Academy of Floral Games of Montauban. One award was for a speech praising King Louis XII. Another was for a speech about Franc de Pompignan. He also wrote an essay about an old stone with Latin words. This earned him a spot in the Toulouse Academy of Sciences.

In 1785, Barère married a wealthy young woman. However, he later wrote that his marriage was "one of the most unhappy."

In 1789, he was chosen to represent Bigorre at the Estates-General. This was a big meeting of representatives from all over France. At first, Barère supported a constitutional monarchy, meaning a king with limited power. He became known more as a journalist than a speaker. His newspaper, Point du Jour, became famous partly because of a drawing by Jacques-Louis David. The drawing showed Barère writing a report during the Tennis Court Oath.

Political Career (1789–1793)

Barère was elected to the Estates-General in 1789. In 1791, he became a judge in the Constituent Assembly.

After King Louis XVI tried to escape in June 1791, Barère joined the republican party. This group wanted France to be a republic without a king. He also stayed in touch with the Duke of Orléans, whose daughter he taught. From October 1791 to September 1792, Barère worked as a judge in France's highest court, the Cour de cassation.

In September 1792, he was elected to the National Convention for the Hautes-Pyrénées region. Barère led meetings in the National Convention. He also chaired the trial of Louis XVI in late 1792 and early 1793. He voted with a group called The Mountain to execute the king. He famously said, "the tree of liberty grows only when watered by the blood of tyrants."

In February 1793, he helped create a committee that wrote a new constitution. On March 18, Barère suggested forming a Committee of Public Safety. He was elected to this committee on April 7. He used his good speaking skills to be the voice of the Committee. He wrote or was the first to sign many orders related to keeping order.

On August 1, Barère reported to the Convention about the Vendée region. The Convention then ordered a harsh crackdown there. On September 5, 1793, Barère gave a speech praising the use of terror. He also supported forming revolutionary armies by the Sans-culottes.

In October 1793, Barère voted for the death of 21 Girondists, another political group. He became known as the "Anacreon Of The Guillotine" because of his role in communicating during the Reign of Terror. He changed his mind about the revolutionary armies in March 1794. He was a key figure in the power struggles between The Mountain and The Plain. He was involved in the events that led to the downfall of Robespierre.

Ideas and Beliefs

After January 1793, Barère started talking about his new belief in "the religion of the fatherland." He wanted everyone to believe strongly in their country. He called for people to be good citizens.

Barère focused on four main ideas about this "religion of the fatherland":

- Citizens were dedicated to their country from birth.

- Citizens should love their country.

- The Republic would teach people good values.

- The country would be a teacher to everyone.

He said that people were born for the Republic, not just for their families. He believed that love for the country would unite everyone.

Barère also promoted nationalism and patriotism. He said, "I was a revolutionary. I am a constitutional citizen." He supported freedom of the press, speech, and thought. He felt that national pride came from strong feelings. These feelings could be awakened by taking part in national activities like public events, festivals, and education. He believed in unity through "diversity and compromise."

In 1793 and 1794, Barère spoke about his ideas. These included teaching national patriotism through universal education. He also believed that everyone owed their nation their services. He said people could serve the nation with their work, money, advice, strength, or even their blood. This meant people of all ages and genders could serve their country. He wanted nationalism to be like a religion, replacing the old national religion of Catholicism.

Barère also believed in basic education for everyone. His ideas about education can still be seen in schools today. For example, in some schools, students recite a pledge of allegiance. They also learn the alphabet and multiplication tables. On March 27, Barère suggested disbanding the revolutionary army in Paris. During the Festival of the Supreme Being, Robespierre was criticized by Barère and other committee members.

Conflicts in the Government

As 1794 went on, there were growing tensions within the Committee of Public Safety. There were also conflicts with other committees and representatives.

Some members of the Committee, like Jean-Marie Collot d'Herbois and Billaud-Varenne, had been very harsh during the Terror. Another group, including Robespierre, Couthon, and Saint-Just, had their own ideas for the Revolution.

Barère later wrote that the Committee of Public Safety had at least three groups:

- The "experts": Lazare Carnot, Robert Lindet, and Pierre Louis Prieur.

- The "high-hands": Robespierre, Couthon, and Saint-Just.

- The "true revolutionaries": Billaud-Varenne, Collot, and Barère himself.

At the same time, the Committee of General Security was the police committee. But its power was reduced by the Law of 22 Prairial. This made members like Marc-Guillaume Alexis Vadier and Jean-Pierre-André Amar worried. These laws made the Revolutionary Tribunal faster and led to many more executions.

Also, some aggressive representatives, like Joseph Fouche, were called back to Paris. They faced questions about their actions in the countryside and feared for their safety.

In this tense situation, Barère tried to find a compromise between these groups. On July 22 (4 Thermidor), Barère offered to help enforce the Ventose Decrees. These decrees involved taking property from enemies of the Revolution. In return, he asked for an agreement not to remove members from the National Convention. Couthon and Saint-Just were somewhat hopeful about these decrees.

However, the next day, Robespierre again said he wanted to remove unnamed enemies from the committees. Saint-Just told Barère he was ready to make some agreements about the Committee of General Security.

Thermidor Crisis (July 1794)

Robespierre continued his path until July 26 (8 Thermidor). He gave a famous speech hinting at threats within the National Convention. A heated debate followed, which Barère eventually stopped. However, members of the Committee of General Security pushed Robespierre for more proof. This led to a fierce argument, and Robespierre did not get the support he expected.

That night, after being kicked out of the Jacobin Club, Collot and Billaud-Varenne returned to the Committee of Public Safety. They found Saint-Just working on a speech for the next day. Barère had been pushing Saint-Just to give a speech about the committees working together. But Collot and Billaud-Varenne thought he was preparing to accuse them. This led to the final split in the Committee of Public Safety. A heated argument broke out. Barère reportedly insulted Couthon, Saint-Just, and Robespierre, saying:

"Who are you then, insolent pygmies, that you want to divide the remains of our country between a cripple, a child and a scoundrel? I wouldn't give you a farmyard to govern!"

The plan to overthrow Robespierre came together that night. Laurent Lecointre started the coup. He was helped by Barère, Fréron, Barras, Tallien, Thuriot, Courtois, Rovère, Garnier de l’Aube, and Guffroy. On July 27 (9 Thermidor), Saint-Just began his speech, but he was interrupted by Tallien and Billaud-Varenne. After some accusations against Robespierre, people called for Barère to speak.

It is said that Barère had two speeches ready in his pocket: one for Robespierre and one against him. Barère played his part by suggesting a law that would weaken the military power of the Paris Commune. He argued that there was no need for a military government in Paris. He said the committees wanted to give the National Guard its democratic organization back. The day after Robespierre's death, Barère called him the "tyrant" and "the Terror itself."

Arrest and Escape

Despite his role in Robespierre's downfall, Barère was still accused of being a terrorist. Before he was sent to prison, Lazare Carnot defended him. However, this defense did not work. On March 22, 1795, the leaders of Thermidor ordered the arrest of Barère and his colleagues from the Reign of Terror, Jean-Marie Collot d'Herbois and Jacques Nicolas Billaud-Varenne.

The court hearings were stopped by an uprising on April 1, 1795. After the uprising was handled, the Assembly voted to send Collot, Billaud, and Barère to French Guiana without further trial. There were big protests in Paris on the day of their deportation.

Barère was accused of betraying King Louis XVI (by voting for his execution), being a traitor to France, and being a terrorist.

The three prisoners were moved to Oléron island to prepare for their journey to Guiana. Barère became very sad in prison and wrote his own epitaph. While the other two prisoners were sent to Guiana, Barère stayed at Oléron.

Meanwhile, political changes in Paris led to a decision to put him on trial again. He was moved to Saintes, Charente-Maritime, where he waited four months for his trial. Eventually, the Convention decided to confirm his old deportation sentence without a new trial.

When Barère found out, his cousin, Hector Barère, and two others helped him escape. Barère was not sure about escaping, but his friends thought he should leave as soon as possible.

According to his own writings, the first plan was to escape over garden walls or from the dormitory with a long rope ladder. This plan failed because the garden was too far, and the dormitory was locked.

The escape plan changed. They decided Barère would escape through the cloister and garden of the convent. Barère escaped on October 26, 1795. A local man named Eutrope Vanderkand also helped him. He went to Bordeaux, where he hid for several years.

In early 1798, while still hiding, he was elected to the Directory's Council of Five Hundred. This was for his home region of Hautes-Pyrénées. However, he was not allowed to take his seat.

In April 1799, the Directory ordered his arrest. So, he left Bordeaux and hid in Saint-Ouen-sur-Seine near Paris.

Later Life and Return

On December 24, 1799, Napoleon offered forgiveness to some politicians, including Barère. During Napoleon's rule, Barère worked on writing. It was rumored that he secretly gave information to Napoleon. Starting in 1803, he published an anti-British magazine called "Le Mémorial anti-britannique," which the government supported. This magazine continued until 1807.

In February 1814, he moved back to his home region in France.

He became a member of the Chamber of Deputies in 1815, during the Hundred Days when Napoleon briefly returned to power.

But when the Bourbons returned to power on July 8, 1815, Barère was banished from France for life. This was because he had voted to execute King Louis XVI. Barère then moved to Brussels, where he lived until 1830. He returned to France and served Louis Philippe during the July monarchy until he died on January 13, 1841.

Barère was the last surviving member of the revolutionary Committee of Public Safety. His memoirs were published after his death in four volumes in 1842.

See also

In Spanish: Bertrand Barère de Vieuzac para niños

In Spanish: Bertrand Barère de Vieuzac para niños

- Society of the Friends of Truth