The Fronde facts for kids

Quick facts for kids The Fronde |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Franco-Spanish War (1635–1659) and the General Crisis | |||||||

Battle of the Faubourg St Antoine (1652) by the walls of the Bastille, Paris |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

||||||

The Fronde was a series of civil wars in France. It happened between 1648 and 1653. This was during the Franco-Spanish War, which had started in 1635.

During the Fronde, young King Louis XIV faced many powerful groups. These included princes, nobles, and law courts called parlements. Most of the French people also opposed him. But in the end, the King won. The trouble began when the French government tried to raise taxes. The parlements argued that these new taxes were against the law. They wanted to limit the King's power.

The Fronde had two main parts: the Parlementary Fronde and the Fronde of the Princes. The first part started right after the Peace of Westphalia in 1648. This peace treaty ended the Thirty Years' War. Many soldiers who had fought in that war were now free. They formed groups that caused trouble in France.

King Louis XIV was very young during the Fronde. He learned a lot from this experience. Later, he made the French army much stronger. He also made sure that army leaders answered only to him. Cardinal Mazarin, who was the King's chief minister, handled the crisis. He came out of it stronger. The Fronde was the last time French nobles tried to fight the King. They lost badly. In the long run, the Fronde made the King's power much greater. It helped create a system of absolute monarchy, where the King had total control.

Contents

What Does "Fronde" Mean?

The French word fronde means "sling". Parisian crowds used slings to break the windows of people who supported Cardinal Mazarin. This is how the conflict got its name.

Why Did the Fronde Start?

The Fronde did not start as a revolution. People wanted to protect old "liberties" from the King's growing power. They also wanted to defend the rights of the parlements. These were high courts, not like the English parliament that makes laws. The most important was the Parlement of Paris. It wanted to limit the King's power. It could do this by refusing to record new laws that went against old customs.

These "liberties" were not about individual freedom. They were about special rights given to towns and officials. France was a mix of local interests and different regions. The Fronde showed how messy this system was. In the end, the chaos of the Fronde actually helped the King gain more power. It made people want a strong ruler to bring order.

The main reason for the trouble was money. The King needed a lot of money to pay for recent wars. So, the government raised taxes. The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) was very expensive. Cardinal Mazarin's government tried to get money through old taxes like the impôts, the taille, and the aides. The nobles refused to pay these taxes. They said they had special old rights. So, the burden of taxes fell mostly on the middle class, called the bourgeoisie.

The movement soon split into different groups. Some wanted to remove Mazarin from power. Others wanted to undo the changes made by his helper, Cardinal Richelieu. Richelieu had taken power away from the great nobles. Some of these nobles became leaders of the Fronde.

When Louis XIV became king in 1643, he was just a child. Richelieu had died the year before, but his ideas still shaped France. Most historians believe that Louis's later decision to rule with total power came from these events in his childhood. The word frondeur later meant anyone who thought the King's power should be limited. Today, in France, it can mean someone who challenges authority.

First Fronde: The Parlementary Fronde (1648–1649)

In May 1648, the government tried to tax judges of the Parlement of Paris. The judges not only refused to pay but also spoke out against earlier tax laws. They demanded that the King accept new rules for the government. These rules were made by a group of all the Paris courts.

There was not much fighting in the Parlementary Fronde. In August 1648, Mazarin heard good news. Louis II de Bourbon, Prince de Condé had won a big victory at Lens. Feeling stronger, Mazarin suddenly arrested the leaders of the parlement. This made the people of Paris angry. They rebelled and built barricades in the streets.

The nobles wanted the Estates General to meet. This was a big assembly of different groups in France. It had last met in 1615. The nobles thought they could control the middle class in this assembly.

The King's side did not have an army ready. So, they had to release the arrested leaders. They also promised to make changes. On the night of October 22, the King's family fled Paris. But France had just signed the Peace of Westphalia (October 24, 1648). This allowed the French army to come back from the borders. By January 1649, Condé had surrounded Paris.

The two sides signed the Peace of Rueil on March 11, 1649. Not much blood was shed. The people of Paris did not like Mazarin. But they refused to ask Spain for help, even though some nobles wanted to. Without Spanish help, the nobles knew they could not win. So, they gave in to the government and received some agreements.

Second Fronde: The Fronde of the Princes (1650–1653)

After the Peace of Rueil, the Fronde changed. It became a series of plots and small fights. People were trying to gain power and control favors. It lost its original goal of changing the government. The leaders were unhappy princes and nobles. These included:

- Gaston, Duke of Orleans (the King's uncle)

- The great general Louis II, Prince de Condé and his brother Armand, Prince of Conti

- Frédéric, the Duke of Bouillon, and his brother Henri, Viscount of Turenne

Other important figures were Gaston's daughter, Mademoiselle de Montpensier, Condé's sister, Madame de Longueville, and Madame de Chevreuse. Also, Jean François Paul de Gondi, who later became Cardinal de Retz, was a clever plotter. The fighting was done by experienced soldiers, led by two great generals and many smaller ones.

January 1650–December 1651

The peace lasted until the end of 1649. The princes were back at court. But they started plotting against Mazarin again. On January 14, 1650, Cardinal Mazarin suddenly arrested Condé, Conti, and Longueville. This time, it was Turenne who led the armed rebellion. Turenne was usually very loyal to the King. But he listened to Madame de Longueville. He decided to rescue her brothers, especially Condé, his old friend from battles.

Turenne hoped to get help from Spain. A large Spanish army gathered in Artois. It was led by Archduke Leopold Wilhelm. But local farmers fought against the Spanish invaders. The King's army in Champagne was led by Caesar de Choiseul. He was 52 years old and had 36 years of war experience. A small fort called Guise successfully fought off the archduke's attack.

Mazarin then took some of Plessis-Praslin's army to fight a rebellion in the south. This forced the royal general to retreat. Archduke Leopold Wilhelm then decided he had spent enough of the King of Spain's money and men. His army went into winter camps. Turenne was left with a mixed group of Frondeurs and other soldiers.

Plessis-Praslin managed to make Rethel surrender on December 13, 1650. Turenne, who was coming to help Rethel, quickly fell back. But he was a tough enemy. Plessis-Praslin and Mazarin were worried about losing a battle. The marshal decided to force Turenne to fight. This led to the Battle of Blanc-Champ (near Somme-Py) or Rethel.

Both sides were in strong positions. Plessis-Praslin was not sure about his cavalry. Turenne was too weak to attack. Then, a fight broke out between two French regiments about who should go first. The King's soldiers had to be rearranged. Turenne saw this confusion and attacked very strongly. The battle on December 15, 1650, was fierce. For a while, it was unclear who would win. But Turenne's Frondeurs finally gave way. His army was destroyed. Turenne realized he was on the wrong side. He asked for and received the young King's forgiveness. Meanwhile, the King's court and loyal troops easily put down smaller rebellions (March–April 1651).

Condé, Conti, and Longueville were set free. By April 1651, the rebellion had ended everywhere. Then came a few months of uneasy peace. The court returned to Paris. Mazarin, who was hated by all the princes, had already gone into exile. His absence left the princes free to fight among themselves. For the rest of the year, France was in chaos.

December 1651–February 1653

In December 1651, Cardinal Mazarin came back to France with a small army. The war started again. This time, Turenne and Condé were fighting against each other.

After this part of the war, the civil war ended. But in other parts of the Franco-Spanish War, these two great generals kept fighting. Turenne defended France, while Condé fought for Spain.

The new Frondeurs started fighting in Guyenne (February–March 1652). Their Spanish allies captured forts in the north. On the Loire River, the Frondeurs were led by plotters and arguing nobles. Then Condé arrived from Guyenne. His brave leadership was clear at the Battle of Bléneau (April 7, 1652). A part of the King's army was destroyed there. But new troops came to fight Condé. Condé realized Turenne was leading the other side. He stopped the battle. The King's army did the same.

Condé invited the commander of Turenne's rear guard to dinner. He joked about how his men had surprised him that morning. As a goodbye, he said, "It's too bad decent people like us are cutting our throats for a scoundrel." This showed the old noble pride. It also showed why Louis XIV later decided to rule with total power.

After Bléneau, both armies marched to Paris. They wanted to talk with the parlement and other leaders. Meanwhile, the Spanish captured more forts. Charles, Duke of Lorraine, with his army of soldiers who liked to steal, marched through Champagne to join Condé. Turenne moved past Condé and blocked the mercenaries. Their leader did not want to fight his men against the old French regiments. So, he agreed to leave for money and two small forts.

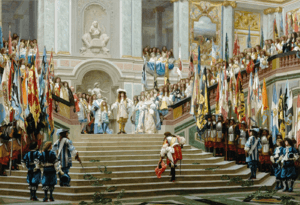

After a few more moves, the King's army trapped the Frondeurs in the Faubourg St. Antoine (July 2, 1652). Their backs were against the closed gates of Paris. The King's soldiers attacked and won a big victory. This was despite the brave fighting of Condé and his nobles. But at the key moment, Gaston's daughter convinced the people of Paris to open the gates. This let Condé's army into the city. She even fired the cannons of the Bastille at the King's soldiers who were chasing them.

A new rebel government appeared in Paris. It named Gaston as the temporary ruler of the country. Mazarin felt that everyone was against him. So, he left France again. The middle-class people of Paris started arguing with the princes. This allowed the King to enter the city on October 21, 1652. Mazarin returned without anyone opposing him in February 1653.

Franco-Spanish War (1635–1659)

The Fronde as a civil war was now over. The whole country was tired of the chaos. They were also disgusted with the princes. People started to see the King's side as the way to have order and a stable government. So, the Fronde helped prepare the way for Louis XIV's total rule.

The larger war continued in Flanders, Catalonia, and Italy. Anywhere a Spanish and a French army faced each other, fighting went on. Condé, with what was left of his army, openly joined the King of Spain's service. This "Spanish Fronde" was mostly about military battles.

In 1653, France was so tired from the wars. Neither side could gather enough supplies to fight until July. At one point, near Péronne, Condé had Turenne in a very bad spot. But he could not convince the Spanish general, Count Fuensaldaña, to attack. The Spanish general cared more about saving his soldiers than helping Condé. So, the armies moved away without fighting.

In 1654, the main event was the siege and relief of Arras. On the night of August 24–25, Turenne's army bravely attacked the walls Condé had built around the city. Condé also gained praise for safely leading his army away. He did this by leading a series of bold cavalry charges himself.

In 1655, Turenne captured the forts of Landrecies, Condé, and St Ghislain. In 1656, Condé got revenge for the defeat at Arras. He stormed Turenne's walls around Valenciennes (July 16). But Turenne still managed to pull his forces back in good order.

The campaign of 1657 was quiet. It is remembered only because 6,000 English soldiers joined the fight. They were sent by Oliver Cromwell as part of his agreement with Mazarin. The English soldiers had a clear goal: to make Dunkirk a new Calais, to be held by England forever. This made the next campaign very important.

Dunkirk was quickly surrounded by a large army. When Don Juan of Austria and Condé arrived with an army to help, Turenne bravely went to meet them. The Battle of the Dunes, fought on June 14, 1658, was the first big test of strength since the battle of the Faubourg St Antoine. Success on one side was canceled out by failure on the other. But in the end, Condé retreated with heavy losses. His own cavalry charges could not make up for the defeat of the Spanish right side among the sand dunes.

Here, the "red-coats" (English soldiers) appeared on a European battlefield for the first time. They were led by Sir William Lockhart, Cromwell's ambassador. They surprised both armies with their fierce attacks. Dunkirk fell and was given to the English Protectorate, as promised. It flew the St George's Cross until Charles II sold it back to the King of France in 1662.

A final, slow campaign followed in 1659. This was the twenty-fifth year of fighting between France and Spain. The Treaty of the Pyrenees was signed on November 5. On January 27, 1660, Condé asked for and received forgiveness from Louis XIV at Aix-en-Provence. Turenne and Condé spent the rest of their lives as loyal subjects of their King.

See also

In Spanish: Fronda (sublevación) para niños

In Spanish: Fronda (sublevación) para niños