Franco-Spanish War (1635–1659) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Franco–Spanish War |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Thirty Years War | |||||||||

Defeat at Rocroi ended Spanish dominance of the European battlefields |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Phase I: 1635-1648 Phase II: 1648-1659 Co-belligerent: (1640–1659) |

Phase I: 1635-1648 Phase II: 1648-1659 |

||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| c. 100,000 (1640s) c. 120,000 (1653) c. 110,000–125,000 (1653–1659) |

77,000 Army of Flanders 1639 | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| Unknown | |||||||||

The Franco-Spanish War was a long conflict between France and its enemies, Spain and the Holy Roman Empire. It lasted from 1635 to 1659. This war was actually two parts: the first part was connected to the Thirty Years War, which ended in 1648 with the Treaty of Westphalia. The second part continued until the Treaty of the Pyrenees in 1659. Many historians see the war as not having a clear winner.

Battles took place in many areas, including Northern Italy, the Spanish Netherlands, Catalonia, and the Rhineland. Spain also supported a French civil war called the Fronde from 1648 to 1653. At the same time, France helped people in Portugal, Catalonia, and Naples who were rebelling against Spanish rule. Both countries also took sides in other smaller conflicts, like the Piedmontese Civil War.

France avoided fighting the Habsburgs directly until May 1635. Then, France declared war on Spain and joined the Thirty Years War. They made alliances with Sweden and the Dutch Republic. After the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648, the Dutch and the Holy Roman Emperor left the war. This left only Spain and France fighting. A civil war in France (the Fronde) and the Dutch navy staying neutral helped Spain regain some lost ground between 1650 and 1652. But soon, neither side could win.

In 1657, France made an alliance with the English Commonwealth. England had been fighting Spain since 1654. A combined attack by England and France in Flanders led to a big victory at the Battle of the Dunes in June 1658. They also captured Dunkirk. Spain was still strong enough to stop France from taking full advantage of this win. However, attacks by the English navy had badly hurt Spain's economy. Both countries were financially exhausted, so they made peace in November 1659.

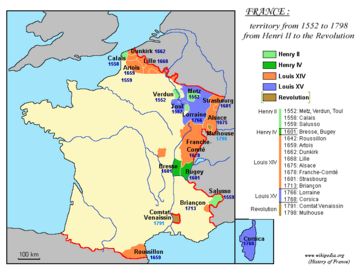

France gained some land, which made its borders stronger. Also, Louis XIV of France married Maria Theresa of Spain, the oldest daughter of King Philip IV. Even though Spain was still a huge global empire, this war is often seen as the end of its time as the most powerful country in Europe. It marked the beginning of France's rise to power.

Contents

Why They Fought: The Big Rivalry

In the 1600s, two powerful families, the Bourbons of France and the Habsburgs of Spain and the Holy Roman Empire, were always competing. This competition was a major reason for many wars in Europe. Historians now see the Franco-Spanish War as part of this bigger, ongoing fight.

Before 1635, France faced problems both inside and outside its borders. Inside, there were religious conflicts. Outside, Habsburg lands surrounded France in places like the Spanish Netherlands, Franche-Comté, Alsace, Roussillon, and Lorraine. To weaken the Habsburgs, France secretly gave money to their enemies, like the Dutch and Swedes. After 1635, France started fighting directly. They made alliances with the Dutch and Swedes and supported rebels in Portugal, Catalonia, and Naples.

The Habsburgs, in turn, supported French nobles who were unhappy with their king, Louis XIII, and his chief minister, Cardinal Richelieu. Spain also helped fund the French civil war known as the Fronde.

The Habsburg family had two main branches: one in Spain and one in Austria (Holy Roman Empire). They didn't always work together perfectly because their goals were different. Spain was a global sea power, while Austria was mostly a land power focused on the Holy Roman Empire.

France also had different goals from its allies. The Dutch Republic was becoming very rich. By 1640, many Dutch leaders worried that France wanted too much land in the Spanish Netherlands. Sweden's war goals were mainly in Germany, and they even thought about making a separate peace with the Holy Roman Emperor.

Much of the fighting happened around the "Spanish Road." This was an important land route that connected Spanish lands in Northern Italy to Flanders. It was vital for trade and went through areas like Alsace, which was important for France's safety. In Northern Italy, Savoy and Spanish-controlled Duchy of Milan were important because they offered access to France's southern borders and Habsburg lands in Austria. Richelieu wanted to end Spain's power in these areas.

Before trains, rivers and ports were the main ways to move goods and armies. Armies often lived off the land by "foraging" (finding food). Feeding the animals needed for transport and cavalry meant that fighting was difficult in winter. By the 1630s, years of war had ruined the countryside. This limited the size of armies and how long they could fight. Sickness killed many more soldiers than battles did. For example, a French army of 27,000 that invaded Flanders in May 1635 was reduced to fewer than 17,000 by early July due to desertion and disease.

How the War Started

The Thirty Years War began in 1618. It started when Protestant leaders in Bohemia offered their crown to Frederick of the Palatinate. They did this instead of giving it to the Catholic Emperor Ferdinand II. Most of the Holy Roman Empire stayed neutral at first. They saw it as a family dispute. The revolt was quickly put down. However, when Frederick refused to give up, Imperial forces invaded his lands and forced him into exile. This changed the war, making it much bigger.

This situation, along with a strong Catholic movement, threatened Protestant states in the Empire. It also brought in other European powers. For example, the Dutch Prince of Orange had lands in the Empire. Christian IV of Denmark was also a German Duke. France was dealing with Spanish-funded religious rebellions from 1622 to 1630. They also fought smaller wars in Italy from 1628 to 1631. These events gave France chances to weaken the Habsburgs without fighting them directly.

France supported the Dutch Republic in their war with Spain. They also funded first Danish, then Swedish armies fighting in the Holy Roman Empire. In 1630, Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden invaded Germany. He wanted to help Protestants and control the Baltic Sea trade, which was important for Sweden's money. Swedish involvement continued even after his death in 1632. However, it led to conflicts with other German states and Denmark. A big defeat at Nördlingen in September 1634 forced the Swedes to retreat. Most of their German allies made peace with Ferdinand in the 1635 Treaty of Prague.

Another major conflict was the Eighty Years' War (1568-1648) between Spain and the Dutch Republic. This war had been paused in 1609. Spain strongly disliked the trade agreements from the pause. When Philip IV became king in 1621, he restarted the war. It was very expensive for Spain. After 1628, a smaller war with France over who would rule Mantua (in Italy) made costs even higher. While the Spanish Empire was at its largest under Philip, its huge size made it hard to manage or change.

In 1628, the Dutch captured the Spanish treasure fleet. They used this money to capture 's-Hertogenbosch in 1629. Some powerful Dutch merchants wanted to end the war. Talks failed in 1633, but more people wanted peace. The Peace of Prague led to rumors that Austria and Spain would attack the Netherlands. This made Louis XIII and Richelieu decide to join the war directly. In early 1635, they made agreements with a German general, Bernard of Saxe-Weimar, and with the Dutch and Swedes, to fight Spain.

Phase I: 1635 to 1648

In May 1635, a French army of 27,000 soldiers marched into the Spanish Netherlands. They defeated a smaller Spanish force at Les Avins and then joined up with the Dutch army. The Spanish commander, Cardinal-Infante Ferdinand, retreated to Leuven. By the time the siege of Leuven began on June 24, many French soldiers had left, reducing their numbers to under 17,000. They pulled back in early July. The Dutch also retreated after losing a fort called Schenkenschans on July 28.

The Dutch leaders did not want more big land battles. Instead, they focused on attacking Spanish trade. In 1636, a Spanish attack reached Corbie in Northern France. This caused panic in Paris, but the Spanish had to retreat because they ran out of supplies. This attack was not repeated. King Philip of Spain focused on getting back lands in the Low Countries. He also fought off French and Savoyard attacks in Italy.

As agreed in 1635, the French took over from Swedish soldiers in Alsace. Before he died in 1639, Bernard of Saxe-Weimar won several battles in the Rhineland. A key victory was the capture of Breisach in December 1638. This cut off the "Spanish Road," forcing Spain to send supplies to their armies in Flanders by sea. The Dutch navy controlled the seas. In 1639, they destroyed a large Spanish supply convoy at the Downs. The Dutch also attacked Portuguese lands in Africa and the Americas, which were then part of the Spanish Empire. Spain's inability to protect these lands caused growing unrest in Portugal.

Damage to the economy and higher taxes led to protests across Spanish lands in the 1630s. In 1640, these protests turned into open revolts in Portugal and Catalonia. In 1641, the Catalan leaders recognized Louis XIII as their ruler. However, they soon found that the new French rule was not much different from the old Spanish one. This made the war in Catalonia a three-way fight between the French-Catalan leaders, the local farmers, and the Spanish.

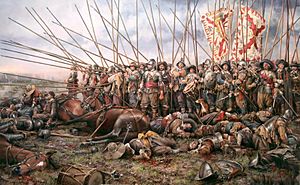

Louis XIII died on May 14, 1643. His five-year-old son, Louis XIV, became king. His mother, Anne of Austria, led the government until he was old enough. Five days after Louis XIII's death, Condé defeated the Spanish army at Rocroi. This battle was very important because it ended Spain's long-standing dominance on European battlefields. Condé was a member of the royal family and a powerful figure. This victory gave him more power in his struggles with Anne and Cardinal Mazarin.

France had some success in Northern France and the Spanish Netherlands, including a victory at Lens in August 1648. But they could not force Spain out of the war completely. In Germany, the Holy Roman Empire won battles at Tuttlingen and Mergentheim. However, France won at Nördlingen and Zusmarshausen. In Italy, French-supported attacks by Savoy against Spanish-ruled Milan did not achieve much. This was due to a lack of resources and the Piedmontese Civil War (1639-1642). Spain remained in control of this region after victories at Orbetello in June 1646 and recapturing Naples in 1647.

The Peace of Westphalia in 1648 ended the Thirty Years War and recognized the Dutch Republic's independence. This stopped the drain on Spain's money. France gained important lands in Alsace and Lorraine, as well as Pinerolo, which controlled access to mountain passes in Northern Italy. However, the peace treaty did not cover Italy, some Imperial lands in the Low Countries, or French-occupied Lorraine. Even though Emperor Ferdinand agreed to stay neutral, the fighting continued.

Phase II: 1648 to 1659

By 1648, both France and Spain were running out of money. King Philip of Spain had to declare bankruptcy in 1647 and 1653. His situation seemed very bad. Much of Flanders was taken over, the important port of Dunkirk was lost, and many of his best soldiers died at Rocroi. However, things got better for Spain after the Peace of Westphalia ended the war with the Dutch. Also, political problems and money troubles led to the French civil war known as the Fronde.

Philip kept fighting, hoping for better peace terms. As the situation in France got worse, Spain made big gains in the Netherlands, including taking back Ypres. In 1650, the revolt in Naples was crushed. By the end of that year, the Catalan rebels controlled Barcelona. When the Fronde ended, Mazarin forced Condé to leave France and go to the Spanish Netherlands. There, Condé made an alliance with Philip. Condé was replaced by Turenne, who was also a skilled commander but had less political power.

Spain recaptured Barcelona in October 1652. Although fighting continued in Roussillon, by 1653 the front lines were stable along the modern Pyrenees border. After the Fronde ended in 1653, France tried again to capture Milan. Milan gave access to the vulnerable southern border of Habsburg lands in Austria. Despite help from Savoy, the Duke of Modena, and Portugal, France failed to achieve this.

By this time, both countries were exhausted. Neither could win a clear victory over the other. From 1654 to 1656, France won battles at Arras, Landrecies, and Saint-Ghislain. But Spain also won battles at Pavia (in Italy) and Valenciennes. Pope Alexander VII pressured Mazarin to offer peace. But Mazarin refused to agree to Spain's demand that Condé get back his French titles and lands. Philip felt he had to help Condé, and since the war seemed to be going his way, he rejected the peace talks.

Before the 1660s, France did not have a strong navy of its own. It relied on the Dutch navy, but the Dutch stopped helping after 1648. Since 1654, Spain had been fighting a naval war with the English Commonwealth. In 1657, Mazarin arranged an alliance between England and France. France had to stop supporting the exiled Charles II, who was the former king of England. As a result, some of Charles II's supporters joined the Spanish side.

In 1658, England and France launched an attack in North Flanders. Their main goal was Dunkirk, a port used by Spanish privateers (private ships allowed to attack enemy ships) against English shipping. After the loss of Dunkirk in June, Spain asked for a truce. Mazarin first refused. However, Oliver Cromwell's death led to political chaos in England. Also, French allies Savoy and Modena ended the war in Northern Italy by agreeing to a truce with the Spanish commander.

Treaty of the Pyrenees and the Royal Marriage

On May 8, 1659, France and Spain began talking about peace terms. The death of Oliver Cromwell in September 1658 weakened England. England was allowed to watch the talks but was not part of them. The Anglo-Spanish War was paused after Charles II became king again in 1660. It officially ended with the Treaty of Madrid in 1667.

The Treaty of the Pyrenees was signed on November 5, 1659. Under this treaty, France gained Artois and Hainaut along its border with the Spanish Netherlands. France also gained Roussillon, or Northern Catalonia. These gains were more important than they might seem. Combined with the 1648 Treaty of Münster, France made its eastern and southwestern borders much stronger. In 1662, Charles II sold Dunkirk to France. Gaining Roussillon set the border between France and Spain along the Pyrenees mountains. But it also split the historic region of Catalonia. This event is still remembered each year by French Catalan-speakers in Perpignan. Besides these land losses, Spain had to officially accept all the land France had gained in the Peace of Westphalia.

France stopped supporting Afonso VI of Portugal. Louis XIV gave up his claim to be the Count of Barcelona and king of Catalonia. Condé got back his lands and titles, as did many of his followers. But his political power was broken, and he did not lead an army again until 1667.

A very important part of the peace talks was the marriage contract between Louis XIV and Maria Theresa. Louis XIV later used this marriage to claim land in the 1666-1667 War of Devolution. It also formed the basis of French claims for the next 50 years. The marriage became even more important because Philip IV's second wife had a second son shortly after the agreement. Both of Philip's young sons died. Philip IV died in 1665, leaving his four-year-old son Charles as king. Charles was often described as "always on the verge of death, but repeatedly baffling Christendom by continuing to live."

What Happened Next and How Historians See It

Older historians often saw this war as a clear French victory. They believed it marked the start of France becoming the most powerful country in Europe, replacing Spain. However, more recent historians argue that this view is based on looking back with hindsight. They say that while France made important gains around its borders, the outcome was much more balanced. They suggest that both sides basically agreed to a draw. If France had not lowered its demands in 1659, the war might have gone on forever.

One historian said that the 1659 treaty was "a peace of equals." Spain's losses were not huge, and France even gave back some land and forts. While looking back, historians might see it as the "decline of Spain" and the "rise of France," at the time, it did not seem like a final decision on who was more powerful.

Another historian noted that "Spain maintained her supremacy in Europe until 1659." Spain was also the greatest empire for many years after that. Even though Spain's economic and military power declined sharply after 1659, it was still a major player in European alliances against Louis XIV. Spain also took part in peace talks in 1678 and 1697.

David Parrott, a history professor at Oxford, says that both the Peace of Westphalia and the Treaty of the Pyrenees showed that both sides were exhausted and stuck. He calls the Franco-Spanish War "25 years of indecisive, over-ambitious and, on occasions, truly disastrous conflict."

Images for kids

-

The Battle of Rocroi (1643) is often seen as the end of the battlefield supremacy of the tercios.

-

The Spanish retake Naples, April 1648; high taxes imposed to pay for the war led to revolt in October 1647

See also

In Spanish: Guerra franco-española (1635-1659) para niños

In Spanish: Guerra franco-española (1635-1659) para niños