Battle of the Downs facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of the Downs |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Eighty Years' War | |||||||

The Battle of the Downs by Willem van de Velde, 1659, RijksMuseum. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Antonio de Oquendo Lope de Hoces † Miguel de Horna |

Maarten Tromp Witte de With Joost Banckert Johan Evertsen |

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 22 galleys, 29 galleons, 13 frigates, 6,500 sailors, 8,000 marines, 30 transports carrying 9,000 soldiers |

95 warships | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 35 ships 5,000 sailors or marines 3,000 soldiers captured or interned in England |

100–1,000 men 1–10 ships lost |

||||||

The Battle of the Downs happened on October 21, 1639. It was a big naval battle during the Eighty Years' War, a long fight between Spain and the Dutch Republic. A Spanish fleet, led by Admiral Antonio de Oquendo, was completely defeated by a Dutch force. This force was under the command of Lieutenant-Admiral Maarten Tromp.

This important Dutch victory stopped Spain from trying to control the English Channel by sea. It also showed that the Dutch were now the main power on the seas. Some people say this battle was the first time a new fighting style called "line of battle" tactics was used.

The battle started when Spain's chief minister, Olivares, sent many troops and supplies to Flanders. These were carried by about 50 warships. For years, Spain had tried to avoid big fights with the stronger Dutch navy. Instead, they attacked Dutch merchant ships from bases in Dunkirk. But this time, Olivares wanted a big victory to make Spain look strong again. He hoped it would force the Dutch to make peace.

The Spanish fleet entered the English Channel on September 11. The Dutch navy met them between September 16 and 18. Not many ships were lost on either side. But Oquendo's fleet had to hide in The Downs. This was a safe place between the English ports of Dover and Deal. England was neutral, so the Spanish were protected there. Even though the Dutch fleet surrounded them, most of the Spanish soldiers were secretly moved to Dunkirk using small, fast ships called frigates.

On October 21, the Dutch fleet entered the Downs and attacked the Spanish. They used special ships called fireships, which were filled with burning materials. The Spanish ships could not move well in the crowded waters. The wind was also against them. About ten Spanish ships were captured or destroyed. Another twelve ships were deliberately run aground to avoid being captured. This battle, along with another defeat in January 1640, showed Spain that they could not win the war at sea. They accepted that the Dutch were now the masters of the ocean.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened

When the war between France and Spain started in 1635, Spain was already fighting two other big wars. They were in the Eighty Years War with the Dutch Republic. They were also helping Emperor Ferdinand II in the Thirty Years War.

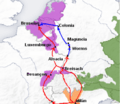

Spain had many resources, more than any of its enemies. But fighting on so many fronts meant they had long supply lines. These lines were easy to attack. The most important one was the "Spanish Road." This was a land route that moved soldiers and supplies from Spain's lands in Italy to their army in Flanders. This route was very important because the Dutch navy was so strong at sea. It was hard for Spain to send supplies by ship.

In December 1638, a French-backed army captured Breisach. This cut off the Spanish Road. However, Spain had defeated Dutch attacks on Dunkirk and Ostend. This made Spain's chief minister, Olivares, feel confident. He decided to send a large group of ships to Flanders to make Spain's navy look strong again.

By August 1639, Olivares had gathered about 50 warships. He also had many smaller ships. These ships had 6,500 sailors and 8,000 marines. They also carried 9,000 extra soldiers and a lot of money for the army in Flanders. These were on 30 transport ships. Some of these ships were rented from England, thanks to a deal with King Charles I. This deal was called the "English Road." It let Spain use England's neutral status to ship supplies and men to Dover. From there, smaller, faster ships took them across the English Channel to Dunkirk.

Since 1621, Spain had avoided big fights with the Dutch navy. They preferred to use ships from Dunkirk to raid Dutch trading ships. But now, Olivares wanted a full-scale battle. He offered command to Lope de Hoces, but he refused. He thought his ships, especially the galleys, were not good for fighting in the Channel. So, the command went to Antonio de Oquendo. Olivares expected the Dutch to try and stop the Spanish ships. This would give Oquendo a chance to fight them.

The Dutch government, called the States General, started getting their main fleet ready. While they did this, a group of ships led by Maarten Tromp was sent to watch the Spanish. He was told not to fight them until the rest of the Dutch fleet arrived. This was about fifty more ships under Johan Evertsen. Tromp split his ships into three groups. One group watched the north, one watched the English side of the Channel, and Tromp's group watched the French coast.

First Fights: September 16-18

The Spanish fleet sailed on August 27 and entered the Channel on September 11. The ships were mixed up so that smaller ships would have bigger ones to support them. The front part of the fleet had thirteen ships from Dunkirk. These ships knew the Channel waters best.

On September 15, the Spanish learned that a Dutch group of ships was near Calais. The next day, they met Tromp's ships. Oquendo arranged his ships in a half-moon shape. Even though he had fewer ships, Tromp put his ships in a "line of battle" and attacked. Oquendo tried to fight Tromp's main ship directly, like he had done in an earlier victory. But he did not give clear orders to his other ships. This meant his large fleet became messy. Only the Dunkirk ships and one other ship stayed with Oquendo as he chased Tromp's ship.

If Oquendo had ordered a proper line, his huge fleet might have surrounded the Dutch ships quickly. But Oquendo seemed focused on boarding Tromp's ship. He missed his chance to fire and sailed past Tromp's ship. He then tried to board the next Dutch ship, but it also avoided him. Oquendo's ship and one other Spanish ship were now downwind. This meant they were getting hit by cannons from the other nine Dutch ships. Tromp turned his ships and attacked the Spanish ship again. Oquendo's other ships could not turn into the wind to help. Their cannons did little damage, but their muskets hit many Dutch sailors.

This fight lasted for three hours. One Dutch ship accidentally exploded. By noon, six more Dutch ships had joined Tromp, making his total 16. The rest of the Spanish fleet was still spread out. But many Spanish ships were finally turning and coming closer. For Tromp, this was getting dangerous. The Spanish ships upwind could block his escape. This would force the Dutch ships into shallow waters near Boulogne, where they would likely get stuck. But at this moment, Oquendo ordered the Spanish fleet to go back to the half-moon shape. The Spanish ships turned, which allowed Tromp's ships to turn too. They gained the wind and escaped the danger.

There were no more fights that evening. The fleets anchored. The next day, more Dutch ships arrived, bringing Tromp's total to 32. But there was no battle, just preparations for the fight on September 18.

The Spanish ships, whose main goal was to protect the soldiers, not to keep fighting, hid in The Downs. This was a safe place near an English group of ships. Oquendo ordered 13 of his fast Dunkirk ships to sail north at night. They went around the Goodwin Sands. Even though the Dutch later blocked this exit, these ships reached Dunkirk with 3,000 soldiers and all the money for the army. In the end, the Spanish said 6,000 soldiers made it to Flanders. About 1,500 were captured by the Dutch, and another 1,500 were killed or stayed in England. This allowed Oquendo to say he had mostly completed his mission.

On September 28, Tromp and De With left to get more supplies, as they were low on gunpowder. They thought they had failed. But on September 30, they found the Spanish ships still at the Downs. They surrounded the Spanish fleet and quickly asked for more ships from the Netherlands. The Dutch hired any large armed merchant ship they could find. Many joined, hoping to get rich from captured Spanish goods. By the end of October, Tromp had 95 ships and 12 fireships.

Meanwhile, the Spanish had already sent 13 or 14 Dunkirk ships through the blockade. They started moving their soldiers and money to Flanders on British ships, using an English flag. Tromp stopped this by searching the English ships and taking any Spanish soldiers he found. He was worried about how England might react. So, he pretended to show the English admiral, Pennington, secret orders. These orders supposedly told him to attack the Spanish fleet wherever it was and to stop any other country from interfering.

The Main Battle

On October 21, the wind was blowing from the east. This gave Tromp the "weather gage," meaning he had an advantage. Tromp sent 30 ships to stop the English admiral, Pennington, from getting involved. Two other groups of ships blocked the escape routes to the north and south. Then, Tromp attacked with the rest of his fleet, including several fireships. Some of the large Spanish ships panicked as the Dutch came closer. They were hard to steer. Many deliberately ran themselves onto the shore. English people watching the battle quickly started taking things from these stranded ships. Others tried to break through the Dutch blockade.

Oquendo's main ship, the Santiago, came out first, followed by the Santa Teresa, the main Portuguese ship. Five burning fireships were sent towards the Spanish ships. The first Spanish ship managed to avoid three fireships. But these hit the Santa Teresa, which had just pushed away two others. The Santa Teresa was the biggest and slowest ship in the Spanish fleet. It could not move fast enough. A fireship grabbed onto it and set it on fire. Admiral Lope de Hoces was already dead from his wounds. The Santa Teresa burned fiercely, and many lives were lost.

The Portuguese ships were met by a Dutch group led by Vice-Admiral Johan Evertsen. He also sent fireships at them. Most Portuguese ships were captured or destroyed. Some reports say 15,200 people died and 1,800 were captured. But this number is now thought to be too high. For example, many soldiers had already reached Flanders. Oquendo managed to escape in the fog with about ten ships, mostly Dunkirk ships. They reached Dunkirk. Nine of the ships that ran aground during the battle were later refloated and also reached Dunkirk.

What Was Lost

A Spanish historian, Cesáreo Fernández Duro, said that 38 Spanish ships tried to break through the Dutch blockade. Twelve of these ships ran aground on the English shore. Nine of those were later refloated and made it to Dunkirk. One ship was destroyed by a fireship. Nine others were captured. Three of these were so badly damaged they sank before reaching port. Another three were wrecked on the coasts of France or Flanders while trying to escape.

A French diplomat, Comte d'Estrades, wrote that the Spanish lost thirteen ships that were burned or sunk. Sixteen were captured, with 4,000 prisoners. He also said fourteen were lost off the coasts of France and Flanders. This number is higher than the total Spanish ships at the Downs. D'Estrades also reported that the Dutch lost ten ships.

The Dutch sources only mention one Dutch ship lost. It got caught with the Santa Teresa. They also say about one hundred Dutch people died. Historian M.G. de Boer's research confirms this. He says Spanish losses were about 40 ships and 7,000 men.

After the Battle

The Dutch victory was a big moment. It showed a change in who was strongest at sea. However, most of the Spanish soldiers and all the money still reached Flanders. Many of the Spanish ships that escaped were badly damaged. Spain was already struggling with the costs of the Thirty Years War. They were not in a good position to rebuild their navy.

Fighting over trade continued between the Dutch and the Dunkirk ships. But these Spanish supply convoys paid a high price in lives and ships. These difficult operations in the Low Countries left Spain's forces and money in a tough spot. The Dutch, English, and French quickly took advantage. They captured some small Spanish islands in the Caribbean. But the worst effect for Spain was how much harder it became to keep control of the Southern Netherlands.

Tromp was celebrated as a hero when he returned. He was given 10,000 guldens. This made another Dutch admiral, De With, jealous, as he only got 1,000. De With wrote anonymous papers saying Tromp was greedy and that he was the real hero.

Spain slowly lost its strong naval position. England was weak, and France did not yet have a strong navy. So, the Dutch let their own navy get much smaller after a peace treaty was signed in 1648. This meant they had a weak navy and too few ships. They were at a big disadvantage in later fights with the English. However, they kept their strong trading advantage over England. The Dutch entered a time of growing power at sea, both in trade and navy, from the Second Anglo-Dutch War until the 1700s.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Batalla de las Dunas (1639) para niños

In Spanish: Batalla de las Dunas (1639) para niños