Army of Flanders facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Army of Flanders |

|

|---|---|

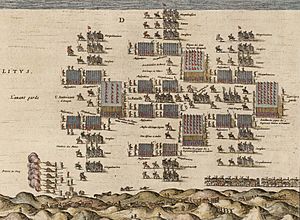

The Army of Flanders' deployment for the Battle of Nieuwpoort (1600).

|

|

| Active | 1567–1706 (dissolution) |

| Country | |

| Allegiance | King of Spain as hereditary prince of the Low Countries |

| Branch | Spanish Army |

| Type | Tercio |

| Role | Security, control, and defense of the Spanish Netherlands |

| Size | 10,000 (1567) 86,235 (1574) 49,765 (1607) 77,000 (1639) |

| Garrison/HQ | Brussels |

| Disbanded | 1706 |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Duke of Alba Julián Romero Sancho Dávila Duke of Parma Ambrosio Spínola Cardinal-Infante Ferdinand Marqués de Assentar Sebastian Fernandez de Medrano |

The Army of Flanders (Spanish: Ejército de Flandes Dutch: Leger van Vlaanderen) was a powerful army that served the kings of Spain. It was based in the Spanish Netherlands (which is now Belgium and Luxembourg) from the 1500s to the 1700s. This army was special because it was one of the longest-serving armies of its time. It was active from 1567 until it was officially ended in 1706.

The Army of Flanders fought in many important conflicts. These included the Dutch Revolt (1567–1609) and the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648). It was considered a very modern army for its time. It had permanent groups of soldiers called tercios, special places for soldiers to live called barracks, and even military hospitals. These ideas were used by the Army of Flanders long before other armies in Europe adopted them. Because of this, some people see it as the world's first truly professional standing army.

The army was very expensive to keep going. Supplies and soldiers had to travel long distances from Spain along a route called the Spanish Road. Despite its strength, the Army of Flanders also became known for its many mutinies. These were times when soldiers refused to follow orders, often because they hadn't been paid. One famous event was the Sack of Antwerp in 1576, where mutinous soldiers caused great destruction.

Contents

How the Army of Flanders Started

The Army of Flanders was one of the longest-lasting armies in the early modern period. It operated for over 130 years, from 1567 to 1706. It was created because of problems in the Netherlands in 1565 and 1566. At that time, the Spanish King Phillip II ruled these provinces. When protests and unrest grew, he decided to send a stronger army. This was to deal with the rebellion and also with new religious ideas (Calvinism) that were spreading.

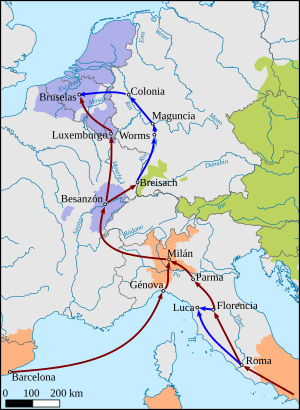

King Phillip's lands were spread across Europe. The new army for the Netherlands was planned to be made up of soldiers from different parts of his empire. In 1567, the plan was to send 8,000 Spanish foot soldiers and 1,200 horsemen. They would travel from northern Italy through friendly lands. This route became known as the 'Spanish Road'.

Initially, the Spanish thought about sending as many as 70,000 soldiers. But they soon realized this would be too much and too costly. In the end, about 10,000 Spanish soldiers and a group of German infantry were sent. Their journey north was a huge achievement for that time. When they arrived, they joined 10,000 Walloons and Germans already there. The new army, led by the Duke of Alba, took strong actions against many people.

Soldiers and Support for the Army

The size of the Army of Flanders changed over time, depending on the challenges it faced. In 1567, it started with just over 20,000 soldiers. After a rebel leader, William I of Orange, was defeated, the Spanish planned for a smaller, permanent force. But the ongoing Dutch revolt meant the army had to grow much larger. By 1574, it was supposed to have 86,000 soldiers, though it might not have reached that number in reality.

This army was made up of soldiers from many different places. They came mainly from the Catholic parts of the Habsburg lands. But there were also soldiers from Britain, Ireland, and even Lutheran parts of Germany. Spanish soldiers were generally seen as the best. Then came Italians, followed by English, Irish, and Burgundian troops. Germans were next, and finally local Walloons. Spanish soldiers were not very popular with the local people. Sometimes, they were even sent out of the Netherlands to calm things down.

Soldiers were recruited in different ways. Some were volunteers signed up by special captains. Others were hired by contractors from all over Europe. About a quarter of the army's soldiers had already served in other armies. More than half were recruited from outside the Netherlands. This system allowed the army to grow quickly when needed. For example, in 1572, the army increased a lot, which was a big success for Spain. Later, it became harder to find experienced soldiers. Other armies, like those in France and Hungary, also needed good fighters.

The cost of recruiting soldiers caused problems for King Philip II. He needed to pay for the Army of Flanders, but also for his navy in the Mediterranean Sea. Sometimes, to get enough soldiers, Spain even sent Catalan criminals to fight in Flanders. Soldiers' pay stayed mostly the same for a long time.

Important leaders of the Army of Flanders usually came from noble families. Having high-ranking noble commanders was very important for this army. Like most armies of that time, it also had many camp followers. These were people from lower classes who traveled with the army. They made the army much larger and needed a lot of supplies during campaigns.

Over time, the Army of Flanders developed modern ideas for its soldiers' well-being. These ideas were often adopted before other European armies. In 1567, a military hospital was set up near Mechelen. It closed for a while but reopened in 1585. It grew to have 49 staff and 330 beds. There was also a permanent home for injured soldiers. In 1596, a public trustee was appointed to manage the belongings of soldiers who died. After 1609, small barracks were built away from cities to house the army. Other nations later copied this idea.

How the Army Fought

The Army of Flanders was built around the Spanish tercio. This was a group of infantry soldiers who mainly used long spears called pikes. This formation worked well in the Netherlands. The land was mostly flat, with many rivers and canals. There were also many towns and cities, which were often protected by strong, modern polygonal fortifications.

Because of these defenses, warfare in the Eighty Years' War mostly involved sieges, not big open battles. A siege is when an army surrounds a city or fort to try and capture it. Away from the big sieges, the war often involved smaller fights, almost like guerrilla tactics. Both the Army of Flanders and the Dutch forces were spread out across the countryside. For example, in 1639, almost half of the army's 77,000 soldiers were in 208 small garrisons (military bases).

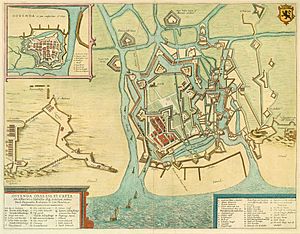

Siege warfare was very costly, both in terms of soldiers and money. The siege of Bergen-op-Zoom in 1622 cost the Spanish commander Spinola 9,000 men. The siege of Oostend from 1601-1604 caused 80,000 casualties for the Army of Flanders. The siege of Breda in 1624–1625 was so expensive that the army had to stop its advance because there was no more money.

In the 1600s, the fighting slowly changed. The borders between Spain and the Dutch became more secure, and there were fewer sieges. The Army of Flanders adapted to these changes. After fighting the Swedish army, who used more flexible tactics, the Spanish decided to change their tercios in 1634. They decided to have more musketeers (soldiers with guns) and fewer pikemen. This gave them more firepower but made them weaker against cavalry. This was shown at the Rocroi (1643).

The army also tried to use heavier muskets instead of lighter arquebuses. But new recruits were often not strong enough to lift the heavier weapons. The Army of Flanders usually needed more infantry (foot soldiers) for fights in the north against the Dutch. It needed more cavalry (horse soldiers) for fights in the south against the French. However, the army rarely had a strong cavalry force. Horses were often hard to find.

Even though the army was sometimes ill-disciplined off the battlefield, it was known for being very disciplined in battle. They were cohesive and had good support. They could achieve impressive military feats, like building a bridge over the Seine river in 1592 to escape.

The Army's Role in the Dutch Revolt (1569–1609)

The Army of Flanders played a key role in all the campaigns of the Dutch Revolt. The Duke of Alba first brought the army to Flanders. Even after losing the Battle of Heiligerlee, he managed to calm the northern areas. But rebel activity started again in 1572. Alba sent his son Fadrique with about 30,000 men to stop the uprising.

The Army of Flanders quickly defeated the weak defenses of Zutphen. They then moved towards Haarlem in December 1572. Haarlem had about 4,000 soldiers and its citizens fought bravely. The Spanish attacked the city for weeks. They even tried digging tunnels to blow up the walls, but the Dutch dug their own tunnels and fought back underground. During winter, the Dutch smuggled supplies into the city over the frozen Haarlem Lake. Even after the ice melted, they used boats in thick fog to bring supplies. Both sides fought fiercely, causing many losses.

Fadrique was so frustrated that he asked his father if he could stop the siege. But the Duke of Alba refused. The turning point came in April 1573 when Spanish ships defeated the Dutch on Haarlem Lake. This stopped the supplies to the city. William of Orange sent 5,000 men to help Haarlem, but the Spanish ambushed them. After seven months, the city surrendered.

After the siege, King Philip sent money to fight the Ottoman Turks, so the Army of Flanders didn't get paid. This led to a mutiny. They failed to capture Alkmaar and Leiden. Alba was replaced by Luis de Zúñiga y Requesens in 1573. The Army of Flanders still had strong soldiers. For example, Sancho d'Avila and his men defeated a German mercenary army in 1574, causing many losses for the Dutch.

Requesens faced problems when the Spanish Crown went bankrupt in 1575. He had no money for his army. The Army of Flanders mutinied again. After Requesens died in 1576, the army almost fell apart into different rebellious groups. Don John of Austria tried to bring order back but couldn't stop the Sack of Antwerp. This was a terrible event where many houses were destroyed and many people died. Because of this, the Dutch provinces signed the Pacification of Ghent. This agreement aimed to remove all Spanish soldiers from the Netherlands. Don John tried to calm things by removing his Spanish troops in 1577, but he had to call them back when the situation worsened.

When Alexander Farnese took command in 1578, the Netherlands was divided. The northern provinces were rebelling, while the southern ones were loyal to Spain. Farnese brought in more troops from Spain and began to strengthen Spanish control in the south. He started with the Siege of Maastricht in March 1579. His troops dug tunnels to attack the walls, and the people of Maastricht dug back. There was fierce underground fighting. Many Spanish soldiers died from boiling water or lack of oxygen in the tunnels. Another 500 died when a mine exploded too early. But on June 29, Farnese's troops managed to enter the city while the tired defenders were asleep.

By 1585, Farnese had recaptured important cities like Brussels, Ghent, and Antwerp. At this point, the army's focus shifted from fighting the Dutch rebels to dealing with England, which was at war with Spain. Farnese believed the army could cross the English Channel. But King Philip decided to use the Spanish Armada (a large fleet of ships) instead. The Army of Flanders prepared to support the Armada, but the defeat of the Spanish fleet ended these plans.

Farnese was later replaced by other commanders. By the time Archduke Albert of Austria took charge in 1595, the Dutch north was becoming an independent country. It was protected by the skilled commander Maurice of Orange and his Dutch States Army. The Dutch continued to capture towns through successful sieges. Meanwhile, the Army of Flanders was increasingly used to fight France in the south. It fought in sieges like Paris (1590) and Rouen (1592). It also operated in Germany, capturing cities like Neuss (1586). Even though the army didn't retake the north, it remained a strong fighting force until the end of this period.

Mutinies in the Army of Flanders

The Army of Flanders was very well known for its frequent mutinies. These happened especially often in the 1570s. These mutinies, or "alterations," happened because Spain's military goals were too big for its money. Spain had a lot of money from its American colonies, but the cost of such a large army was still too high.

In 1568, defending the army in Flanders cost 1,873,000 florins a year. By 1574, the larger army cost 1,200,000 florins every month! The Netherlands couldn't pay for this, and money from Spain was limited. This money problem was hard to manage even in normal times. In years like 1575, King Phillip II couldn't pay his loans, so there was no money for the Army of Flanders.

Mutinies usually followed. The Army of Flanders mutinied 45 times between 1572 and 1609. These mutinies became almost a formal process. The longest mutiny was the Mutiny of Hoogstraten, which lasted from September 1602 to May 1604.

These mutinies caused three main problems:

- They were unpredictable and scary for military leaders.

- They encouraged soldiers to take food and lodging from local people. This made the locals dislike the Spanish.

- The breaks in fighting caused by mutinies allowed the Dutch to regain land.

The first mutiny happened in 1573. Soldiers were eventually paid, but two more mutinies followed, stopping the Spanish campaign. Mutinies continued in 1575 and 1576. After the army's commander, Requesens, died, the army almost collapsed. Soldiers took money and food from locals, which led to new Dutch revolts. People cried out, "death to the Spaniards!"

The new commander, Don John of Austria, couldn't restore order. This led to the Sack of Antwerp, a terrible event where many houses were destroyed and many people died. Because of this, the Dutch provinces signed the Pacification of Ghent. This agreement united the rebellious and loyal provinces to remove all Spanish soldiers. It also stopped the persecution of people with different religious beliefs. This basically undid all the Spanish achievements of the past ten years. Don John tried to calm things by removing his Spanish troops in 1577. But he had to call them back when the political situation got worse. When Don John died, Alexander Farnese took over. In 1579, his troops caused great suffering in Maastricht.

Role in the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648)

At the start of the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648), the Army of Flanders was an important mobile army for the Emperor's side. From 1618 to 1625, the army, with 20,000 soldiers, was sent under Ambrogio Spinola to help the Emperor. They kept the Protestant Union busy while other forces attacked Bohemia. The Army of Flanders joined with the Army of the Catholic League. Together, they strongly defeated Frederick V at the Battle of White Mountain near Prague in 1620. After this, Bohemia became Catholic again and stayed under Habsburg rule for almost 300 years. The Army of Flanders then moved to outflank the Dutch, preparing for a new attack on the United Provinces.

After its success, the army turned its attention to the Dutch. Spinola made good progress from 1621 onwards. He finally recaptured Breda after a famous siege in 1624. However, this siege cost Spain far too much money. The army then had to fight defensively for the rest of the war.

The army was under increasing pressure. But in 1634, Spain used the Spanish Road again. They brought fresh soldiers from Spanish Italy under the command of the Cardinal-Infante Ferdinand of Austria. These forces destroyed Sweden's army at the Battle of Nördlingen. Then, they moved west to strengthen the Army of Flanders. However, any advantage Spain gained was soon lost. A new alliance between France and the Dutch threatened to trap the Spanish Netherlands between two enemies.

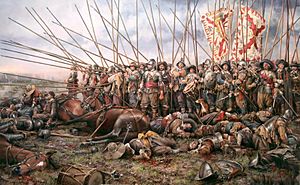

When France joined the war in 1636, the Army of Flanders started well. It counter-attacked and even threatened Paris in 1636. But over the next few years, France's military grew stronger. The Army of Flanders' earlier successes were overshadowed by their defeat at the Battle of Rocroi in 1643. Spain had sent the army from Flanders to northern France. They were threatening to advance on Paris. But the battle, as the army besieged Rocroi, turned against the Spanish. Their defeat became certain. The French commander tried to negotiate a surrender for the remaining Spanish soldiers. But a misunderstanding led to the French attacking the Spanish forces without mercy. Out of 18,000 Spanish soldiers, 7,000 were captured and 8,000 were killed. Most of these losses were the highly valued Spanish soldiers.

Losing so many soldiers had immediate effects. Spain could no longer advance on Paris. Within five weeks, they began talks that led to the 1648 Peace of Westphalia. Many historians believe that the decline of Spanish military power in Europe started with the Battle of Rocroi. However, this defeat can be exaggerated. A large part of the Army of Flanders, about 6,000 men, did not arrive in time for the battle. They formed the core of the new Army of Flanders afterward. Some recent historians say that 1643 is not necessarily the start of the decline. Spain remained powerful and able to defend itself in Flanders for many years after.

The Army's Final Years (1648–1706)

After the Thirty Years' War, Spain's government had less money. So, they steadily reduced the size of the Army of Flanders. This continued after the Franco-Spanish War ended in 1648. Even though it had fewer soldiers and its quality declined, the army was still "an opponent to be treated with respect" until the 1650s. It started to rely more on allied forces, like the army of Louis, Grand Condé and a Royalist Army in Exile. The Battle of Dunkirk in 1658, where the Army of Flanders was defeated by the French, led to a new peace. From 1659, Spain increasingly relied on Dutch and English troops to stop Louis XIV from taking over the Spanish Netherlands. Spain itself became less interested in these lands after more than a century of war.

Recent studies show that Spain's government and military faced deep problems from the 1630s onwards. The Count-Duke of Olivares, a key advisor to King Philip IV, tried to make the Army of Flanders stronger. He put more noblemen into senior positions. But this led to too many officers, a confusing command system, and many temporary appointments. By the 1650s, there was one officer for every four soldiers, which was not sustainable.

Recruitment also changed. By the mid-1600s, soldiers were less often hired by contractors. Instead, men were often captured or chosen by lotteries from cities and towns. The Army of Flanders suffered from this because France had closed the Spanish Road. This meant fewer recruits could come from Spain and Italy. So, the army had to rely on local forces or mercenaries who were not as good as the older soldiers. The army's support services improved, but not as much as in other places. The army was increasingly seen as a "broken force" in Europe. With money still tight, visitors in the late 1600s reported seeing soldiers begging and lacking food.

Despite these problems, the army kept its reputation for being professional. When Spain joined the Franco-Dutch War (1672–1678), three of its tercios were part of the Allied army. In August 1674, they fought near Seneffe. The Spanish infantry held their positions for most of the day, even though they were surprised. Their courage and discipline saved William from a serious defeat. They were finally forced to retreat in the early evening, leaving behind their dead, including their commander.

The Royal Military and Mathematics Academy of the Netherlands

In 1675, the Army of Flanders joined the first modern Royal Military Academy in Europe. This academy, called the Academia Militar del Ejército de los Países Bajos, was founded in Brussels. Its director was Don Sebastián Fernández de Medrano. He was a Battle General and a Master of Mathematics. The academy was started because the Spanish Tercios needed more artillerymen (soldiers who operate cannons) and engineers. The Duke of Villahermosa, who was the Governor of the Habsburg Netherlands, wrote to Charles II in 1680. He said that Medrano was so good that Spain no longer needed engineers from other countries.

Sebastian Fernandez de Medrano chose Francisco Antonio de Agurto Salcedo Medrano as the academy's patron. In 1688, the Army of Flanders, led by the Marquis of Gastañaga, had 25,539 officers and men. By 1689, it grew to 31,743 men. This was the largest the Army of Flanders was during the Nine Years War.

This Royal Military Academy in Flanders was famous for its students coming from many different places. It also had new ways of studying, combining theory and practice. Its officer cadets were even called the “Great Masters of War.” The academy was created in Brussels to train the best officers in the region in the Art of War. It is considered the first general military training project and a forerunner of future military academies.

The academy was very successful. Princes and other important people sent students to be trained by Medrano. Medrano himself said that many engineers were trained there. The Emperor and other princes asked for their services for their armies. For example, in 1694, Maximilian Emmanuel wrote that Medrano's students were working in Hungary and Germany. Many engineers and artillerymen for the Spanish armies in the Netherlands came from this academy. They were also requested by other leaders for the war against Louis XIV.

One student, Reysenberg, became the Emperor's General Engineer in Hungary. Others served King James II of England or the Dukes of Lorraine and Savoy. Many came to Spain in 1711 when Medrano's student, the Marquis of Verboom, organized the Corps of Engineers. Don Sebastian Fernandez de Medrano taught Mathematics and Administration himself. He even wrote the textbooks for his students. The academy taught many subjects important for military engineers, such as arithmetic, geometry, artillery, fortification, algebra, cosmography, astronomy, and navigation. Arithmetic, geometry, and fortification were especially important.

Many engineers trained at this academy were sent to colonial cities in the Americas. From 1694 onwards, Medrano gave out three annual prizes to students. These were gold medals with the image of Charles II of Spain.

The Royal Military Academy of Flanders in Brussels directly influenced the Royal Military Academy of Mathematics of Barcelona in the 1700s. Sebastian Fernandez de Medrano was chosen to be the director of the new academy in Barcelona, but he died in 1705. The Royal Academy of Barcelona continued Medrano's teaching style. It was opened by Lieutenant General Marquis of Verboom, who was a great student of Medrano's academy. The Royal Military Academy of Flanders was important for Spanish fortifications. But when it fell to the French army in 1697, it declined and was officially ended in 1706.

By the end of the 1600s, the Army of Flanders was nearing its end. The War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714) brought French and Allied invasions. The Spanish government became weak, which destroyed the basis of the Army of Flanders. It was officially disbanded in 1706.

Cultural Legacy

The Army of Flanders had a strong influence on Spanish culture. For example, the patron saint of the modern Spanish infantry is the Immaculate Conception. This comes from an event in 1585 during the Battle of Empel. The tercio of Francisco Arias de Bobadilla was trapped on an island by the Dutch navy. It was mid-winter, and his men were running out of food. But de Bobadilla refused to surrender.

One of his soldiers, while digging a trench, found a wooden picture of the Immaculate Conception. De Bobadilla placed it on a makeshift altar and prayed for help. That night, the weather got even colder, and the Meuse river around the island froze over. De Bobadilla's men were able to cross the river on the ice. They raided the Dutch ships and defeated them. After this, the Army of Flanders adopted the Immaculate Conception as their patroness. The modern Spanish infantry later followed this tradition.

Several phrases from the military in Flanders are still used in the Spanish language today:

- Poner una pica en Flandes, – 'to put a pike in Flanders' – means something is extremely difficult or costly. This refers to how expensive it was to send Spanish forces to Flanders.

- Pasar por los bancos de Flandes, – 'to go through the banks of Flanders' – means overcoming a difficulty. This refers to the tricky sandbanks that protected the rivers in the Netherlands.

See also

In Spanish: Ejército de Flandes para niños

In Spanish: Ejército de Flandes para niños

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |