Siege of Haarlem facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Siege of Haarlem |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Eighty Years' War | |||||||

Romanticized historical painting of Kenau leading a group of 300 women in defense of Haarlem, by Barend Wijnveld and J.H. Egenberger, 1854 |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

German Protestants |

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 2,550 infantry and 225 cavalry (Haarlem) 5,000 soldiers (William the Silent) |

17,000–18,000 troops | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 2,000 dead or wounded (Haarlem) 700 - 5,000 dead or wounded (William the Silent) |

1,700 dead thousands of casualties |

||||||

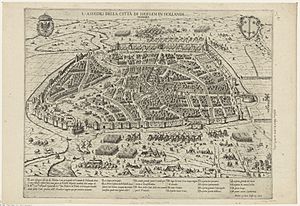

The Siege of Haarlem was an important event during the Eighty Years' War. This war was a long fight for independence by the Netherlands against Spain. From December 11, 1572, to July 13, 1573, a large Spanish army attacked the city of Haarlem. Haarlem, a city in the Netherlands, had recently decided to support the Dutch rebels. After a naval battle and a failed attempt to send help by land, the people in Haarlem ran out of food. The city had to give up, and many of its defenders were killed. Even though Haarlem lost, its strong resistance inspired other Dutch cities like Alkmaar and Leiden to keep fighting.

Contents

Why Haarlem Was Attacked

Haarlem first tried to stay neutral in the religious war happening in the Netherlands. In 1566, it avoided the destruction of religious images that affected other cities. When the city of Brielle was captured by the "Geuzen" (Dutch rebels) in April 1572, Haarlem did not immediately join them.

Haarlem Joins the Rebels

Most city leaders did not want to openly rebel against Philip II of Spain. He was the king of Spain and also ruled the Netherlands. However, after many discussions, Haarlem officially joined the rebels on July 4, 1572.

King Philip II was not happy about this. He sent a large army north, led by Don Fadrique, who was the son of the Duke of Alva. This army was very harsh. On November 17, 1572, many people in Zutphen were killed by the Spanish army. On December 1, the city of Naarden suffered the same fate.

Preparing for Battle

Haarlem's leaders tried to talk with Don Fadrique in Amsterdam. But the city's defenses were led by Wigbolt Ripperda. He was a commander chosen by William the Silent, the leader of the Dutch rebels. Ripperda strongly disagreed with talking to the Spanish. He gathered the city guard and convinced them to stay loyal to William the Silent. The city's government was then changed to include people who supported the rebels. When the leaders who went to Amsterdam returned, they were seen as traitors. The main church, the Sint-Bavokerk, was also cleared of its Catholic symbols that same day.

The Siege Begins

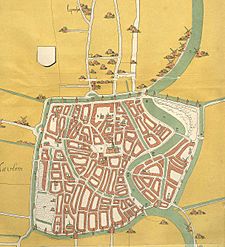

On December 11, 1572, the Spanish army started its attack on Haarlem. The city's defenses were not very strong. Even though Haarlem had walls, they were not in good condition. The land around the city could not be flooded to stop the enemy, which gave the Spanish many places to set up their camps. However, the nearby Haarlemmermeer (a large lake) made it hard for the Spanish to completely stop food from reaching the city.

Fighting in Winter

It was unusual to fight wars in winter during the Middle Ages. But Haarlem was very important, so Don Fadrique stayed and kept the city under siege. For the first two months, the fight was even. The Spanish army dug tunnels to reach the city walls and make them fall down. The defenders also dug tunnels to blow up the Spanish tunnels.

The situation became much worse for Haarlem on March 29, 1573. The army from Amsterdam, which was loyal to the Spanish king, took control of the Haarlemmermeer. This completely cut off Haarlem from the outside world.

Hunger and Heroism

Hunger grew severe in the city. On May 27, many prisoners who were loyal to Spain were taken from prison and killed. On December 19, the Spanish fired 625 shots at one part of the city wall. This forced the defenders to build a completely new wall. Two city gates, the Kruispoort and the Janspoort, also collapsed during the fighting.

Kenau Simonsdochter Hasselaer, a woman whose husband was a shipbuilder, helped repair the city's defenses. Later, a famous story grew that she personally fought and even led an army of 300 women into battle.

In early July, William I of Orange gathered an army of 5,000 soldiers near Leiden to help Haarlem. However, the Spanish army trapped them and defeated William's forces.

The City Surrenders

In the early days of the siege, the Spanish army tried to storm the city walls. But this quick attack failed because the Spanish did not expect such strong resistance. This early victory greatly boosted the defenders' spirits.

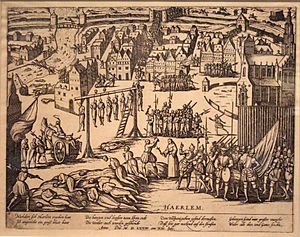

After seven months of fighting, the city of Haarlem surrendered on July 13, 1573. Usually, after a siege, the winning army would be allowed to loot the city. But the people of Haarlem were allowed to pay a large sum of money, 240,000 guilders, to save their city from being looted.

After the Surrender

The Spanish kept their promise not to loot the city. However, almost all the soldiers who defended Haarlem were killed. This included many English, French, and German fighters, except for the Germans. About 40 citizens who were seen as leaders of the rebellion were also put to death. The Spanish ran out of bullets, so many of them were drowned in the Spaarne river. While most citizens could leave, 1,500 of the city's defenders were either beheaded or tied together and thrown into the river. Governor Ripperda and his second-in-command were also beheaded. Don Fadrique thanked God for his victory in the Sint-Bavokerk. The city then had to host a Spanish army.

What Happened Next

Even though Haarlem was lost to the Spanish, the siege showed other cities that the Spanish army was not unbeatable. This idea, along with the huge losses the Spanish army suffered (perhaps 10,000 men), helped the cities of Leiden and Alkmaar in their own sieges. Alkmaar later defeated the Spanish army, which was a major turning point in the Dutch Revolt.

In the Sint-Bavo church in Haarlem, these words can still be read:

In dees grote nood, in ons uutereste ellent

Gaven wij de stadt op door hongers verbant

not that he took her by storm.

Niet dat hij se in creegh met stormender hant.

In this great need, in our uttermost misery,

we gave up the city, forced by hunger,

The Spanish army also faced serious problems with its soldiers after the siege.

Stories and Films

Some Dutch cities celebrate their victories over the Spanish every year. For example, Alkmaar celebrates on October 8, 1573, and Leiden on October 2–3, 1574. Haarlem did not win on July 13, 1573, so it does not have a similar independence celebration. The Siege of Haarlem has been featured in three plays, with one famous play by Juliana de Lannoy in 1770.

The 2014 Dutch film Kenau tells the story of the siege. It highlights the brave actions of the women who helped defend the city.

See also

In Spanish: Asedio de Haarlem para niños

In Spanish: Asedio de Haarlem para niños

| James B. Knighten |

| Azellia White |

| Willa Brown |