William the Silent facts for kids

Quick facts for kids William the Silent |

|

|---|---|

Portrait by Adriaen Thomasz. Key, c. 1570–84

|

|

| Prince of Orange | |

| Reign | 15 July 1544 – 10 July 1584 |

| Predecessor | René |

| Successor | Philip William |

| Stadtholder of Friesland | |

| In office 1580–1584 |

|

| Preceded by | George de Lalaing |

| Succeeded by | William Louis of Nassau-Dillenburg |

| Stadtholder of Holland and Zeeland | |

| In office 1572–1584 |

|

| Preceded by | Maximilien de Hénin-Liétard |

| Succeeded by | Maurice, Prince of Orange |

| In office 1559–1567 |

|

| Monarch | Philip II of Spain |

| Preceded by | Maximilian of Burgundy |

| Succeeded by | Maximilien de Hénin-Liétard |

| Stadtholder of Utrecht | |

| In office 1572–1584 |

|

| Preceded by | Maximilien de Hénin-Liétard |

| Succeeded by | Adolf van Nieuwenaar |

| In office 1559–1567 |

|

| Monarch | Philip II of Spain |

| Preceded by | Maximilian of Burgundy |

| Succeeded by | Maximilien de Hénin-Liétard |

| Born | 24 April 1533 Dillenburg, County of Nassau, Holy Roman Empire |

| Died | 10 July 1584 (aged 51) Delft, County of Holland, Dutch Republic |

| Spouse |

Anna of Saxony

(m. 1561; div. 1571) |

| Issue | 16 |

| Father | William I, Count of Nassau-Siegen |

| Mother | Juliana of Stolberg-Werningerode |

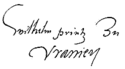

| Signature |  |

William the Silent (born April 24, 1533 – died July 10, 1584) was a very important leader in Dutch history. He is also known as William of Orange in the Netherlands. He led the Dutch Revolt against the Spanish rulers, which started the Eighty Years' War (1568–1648). This war eventually led to the United Provinces becoming an independent country in 1648.

William was born into the House of Nassau family. He became the Prince of Orange in 1544. He is the founder of the House of Orange-Nassau branch, which is the family of the current monarchy of the Netherlands. In the Netherlands, people often call him the Father of the Fatherland.

William was a rich nobleman who first worked for the Spanish Habsburg rulers. He was part of the court of Margaret of Parma, who governed the Spanish Netherlands. However, William became unhappy. He disliked how the Spanish were taking power away from local leaders. He also disagreed with the Spanish persecution of Protestants in the Netherlands. Because of this, William joined the Dutch uprising against his former masters. He became the most important and skilled leader among the rebels. He led the Dutch to many victories against the Spanish. The Spanish king declared him an outlaw in 1580. Sadly, he was assassinated in Delft in 1584 by Balthasar Gérard.

Contents

Early Life and Education

William was born on April 24, 1533, at Dillenburg Castle. This castle was in the County of Nassau-Dillenburg, part of the Holy Roman Empire. Today, this area is in Germany. He was the oldest son of Count William I of Nassau-Siegen and Juliana of Stolberg. William's family was very religious. He was raised as a Lutheran.

In 1544, William's cousin, René of Châlon, who was the Prince of Orange, died without children. In his will, René named William as the heir to all his lands and titles. This included the title of Prince of Orange. There was one condition: William had to get a Roman Catholic education. William's father agreed to this for his 11-year-old son. This is how the House of Orange-Nassau began.

William inherited a lot of land. Besides the Principality of Orange in France, he also got many estates in the Low Countries. These areas are now the Netherlands and Belgium. Because William was so young, Emperor Charles V became his guardian. Charles V was the ruler of most of these lands. He managed them until William was old enough to rule them himself.

William was sent to the Netherlands for his Catholic education. He first stayed at his family's home in Breda. Later, he moved to Brussels. There, he was supervised by Mary of Hungary, the Emperor's sister. In Brussels, William learned foreign languages. He also received training in military and diplomatic skills.

On July 6, 1551, William married Anna. She was the daughter of an important Dutch nobleman. This marriage was arranged by Emperor Charles V. Anna's father had died, so William became Lord of Egmond and Count of Buren when they married. They had a happy marriage and three children. Sadly, one child died very young. Anna passed away on March 24, 1558, at only 25 years old. William was very sad about her death.

William's Career and Rise to Power

Serving the Emperor

William was a favorite of the imperial family. He was appointed a captain in the cavalry in 1551. He quickly rose through the ranks. By age 22, in 1555, he was a commander of one of the Emperor's armies. He was also made a member of the Raad van State. This was the highest political advisory group in the Netherlands.

In November 1555, Emperor Charles V was stepping down. He leaned on William's shoulder during the ceremony. Charles gave control of the Low Countries to his son, Philip II of Spain. William was also chosen to carry the symbols of the Holy Roman Empire to Charles's brother, Ferdinand. This happened when Charles gave up his imperial crown in 1556. William also signed the Treaty of Cateau-Cambrésis in April 1559.

In 1559, Philip II gave William more power. He made William stadtholder (governor) of Holland, Zeeland, and Utrecht. This greatly increased William's political influence. He also became stadtholder of Franche-Comté in 1561.

From Politician to Rebel Leader

William became a leading member of the opposition in the Council of State. He joined with other noblemen like Philip de Montmorency, Count of Hoorn and Lamoral, Count of Egmont. They wanted more political power for themselves and for the Dutch nobility. They also complained that too many Spaniards were involved in governing the Netherlands.

William was also unhappy about the growing persecution of Protestants. He was raised Lutheran and later became Catholic, but he believed in freedom of religion for everyone. The Inquisition was very active in the Netherlands. It was led by Cardinal Granvelle. This increased opposition to Spanish rule among the Dutch people, who were mostly Catholic at the time. The opposition also wanted Spanish troops to leave the country.

William later wrote that his decision to fight the Spanish came from a secret conversation. In 1559, he was in France as a hostage for a peace treaty. King Henry II of France told William about a secret plan. This plan was between Henry II and Philip II of Spain. Their goal was to violently get rid of Protestantism in France, the Netherlands, and everywhere else. King Henry thought William knew about the plan. William did not correct him. But he decided then that he would not allow "so many honorable people" to be killed, especially in the Netherlands, which he cared deeply about.

On August 25, 1561, William married for the second time. His new wife was Anna of Saxony. People at the time described her as difficult. William likely married her to gain more influence in parts of Germany. They had five children together. This marriage used Lutheran traditions. It marked a change in William's religious views. He later returned to Lutheranism and then to a moderate form of Calvinism. Still, he always remained tolerant of other religions.

William used to live a very fancy and expensive life. He had many young noblemen around him. He also kept an open house at his beautiful palace in Brussels. Because of this, he was often in debt, even with his large estates. After returning from France, William began to change. Philip made him a state councilor and governor of Holland, Zeeland, and Utrecht. But there was a hidden disagreement between the two men.

By 1564, William began to openly criticize the King's anti-Protestant policies. In August of that year, Philip ordered that the anti-Protestant rules of the Council of Trent be followed. William gave a famous speech to the Council of State. He shocked his audience by saying that even though he was Catholic, he could not agree that kings should control people's beliefs. He said they should not take away people's freedom of religion.

In early 1565, a group of noblemen, including William's younger brother Louis, formed the Confederacy of Noblemen. They asked Margaret of Parma to stop persecuting Protestants. From August to October 1566, a wave of iconoclasm spread through the Low Countries. This was known as the Beeldenstorm. Calvinists and other Protestants were angry about Catholic oppression. They destroyed statues in hundreds of churches and monasteries.

After the Beeldenstorm, unrest grew in the Netherlands. Margaret agreed to the Confederacy's wishes if they helped restore order. She also allowed important noblemen, like William, to help. William went to Antwerp and stopped the riot there. By late 1566 and early 1567, it became clear that Margaret could not keep her promises. Many Protestants fled the country. Philip II then announced that he would send his general, Duke of Alba, to restore order. William resigned his positions and went back to his home in Nassau in April 1567.

When Alba arrived in August 1567, he created the Council of Troubles. People called it the Council of Blood. It judged those involved in the rebellion. William was called before the Council but did not appear. He was then declared an outlaw, and his property was taken away. As a popular politician, William became the leader of the armed resistance. He funded the Watergeuzen, who were Protestant refugees. They became corsairs and raided coastal cities. William also raised an army of German mercenaries to fight Alba on land.

William allied with the French Huguenots. His brother Louis led an army into the northern Netherlands in 1568. However, the plan failed. The Huguenots were defeated, and a small force was captured. On May 23, Louis's army won the Battle of Heiligerlee. William's brother Adolf was killed in this battle. Alba responded by executing noblemen, including the Counts of Egmont and Hoorn. He then defeated Louis's forces in the Battle of Jemmingen on July 21. These two battles are seen as the start of the Eighty Years' War.

The War for Independence

In October 1568, William led a large army into Brabant. But Alba avoided a direct fight, hoping William's army would fall apart. William's army faced problems, and with winter coming and money running out, he returned to France. William made more plans to invade in the next few years, but they didn't happen because he lacked support and money.

He remained popular with the public. This was partly due to many pamphlets that spread his message. He argued that he was not fighting the King of Spain, but only the bad rule of foreign governors and soldiers in the Netherlands.

On April 1, 1572, a group called the Watergeuzen ("Sea Beggars") captured the city of Brielle. The Spanish soldiers had left the city unguarded. The Watergeuzen occupied the town and raised William's flag. Other cities soon opened their gates to them. Soon, most cities in Holland and Zeeland were controlled by the rebels. Only Amsterdam and Middelburg remained under Spanish control. The rebel cities then called a meeting of the Staten Generaal. They officially made William the stadtholder of Holland and Zeeland again.

At the same time, rebel armies captured cities across the country. William himself advanced with his army into southern cities. He had hoped for help from the Huguenots, but this plan failed. The St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre on August 24 started a wave of violence against Huguenots. After a Spanish attack, William had to retreat to Enkhuizen in Holland. The Spanish then took back several rebel cities, sometimes killing their people. They had more trouble with cities in Holland. They took Haarlem after seven months and lost 8,000 soldiers. They also had to stop their siege of Alkmaar.

In 1573, William joined the Calvinist Church. He appointed Jean Taffin as his court preacher. Taffin later became an important political advisor to William.

In 1574, William's armies won some smaller battles, including naval ones. The Spanish, now led by Don Luis de Zúñiga y Requesens, also had successes. Their victory in the Battle of Mookerheyde on April 14 cost the lives of two of William's brothers, Louis and Henry. Requesens's armies also surrounded the city of Leiden. They stopped their siege when the Dutch broke nearby dikes, flooding the land. William was happy with this victory. He then founded the University of Leiden, the first university in the Northern Provinces.

William married for the third time on April 24, 1575. His new wife was Charlotte de Bourbon-Montpensier, a former French nun. She was also popular with the public. They had six daughters. Their marriage seemed to be based on love and was happy.

Peace talks in Breda failed in 1575, and the war continued. The rebels' situation improved when Don Requesens died unexpectedly in March 1576. A large group of Spanish soldiers, who hadn't been paid, mutinied in November. They attacked Antwerp in what became known as the "Spanish Fury". This event was a huge propaganda victory for the rebels.

Before the new governor, Don Juan of Austria, arrived, William got most provinces and cities to sign the Pacification of Ghent. In this agreement, they promised to fight together to expel Spanish troops. However, they could not agree on religious matters. Catholic cities would not allow freedom for Calvinists.

When Don Juan signed the Perpetual Edict in February 1577, it seemed the war was over. He promised to follow the Pacification of Ghent. However, after Don Juan took the city of Namur in 1577, the uprising spread. Don Juan tried to negotiate peace, but William intentionally let the talks fail. On September 24, 1577, William made a grand entry into Brussels, the capital. At the same time, Calvinist rebels became more extreme. They tried to ban Catholicism in areas they controlled. William opposed this because he wanted religious freedom for all. He also needed the support of less extreme Protestants and Catholics.

On January 6, 1579, some southern provinces signed the Treaty of Arras. They were unhappy with William's radical followers. They agreed to accept their Catholic governor, Alessandro Farnese, Duke of Parma. Five northern provinces then signed the Union of Utrecht on January 23. This confirmed their unity. William initially opposed this Union because he still hoped to unite all provinces. But he formally supported it on May 3. The Union of Utrecht later became like a constitution. It was the only formal link between the Dutch provinces until 1797.

Declaring Independence

Even with the new union, the Duke of Parma successfully took back most of the southern Netherlands. He had agreed to remove Spanish troops from the provinces under the Treaty of Arras. Also, Philip II needed them elsewhere. So, the Duke of Parma could not advance further until late 1581.

In March 1580, Philip II issued a royal ban against William. He promised a reward of 25,000 crowns to anyone who killed him. William responded with his Apology. This document defended his actions and strongly criticized the Spanish king. It also restated William's Protestant loyalty.

Meanwhile, William and his supporters looked for foreign help. William had asked France for help before. This time, he got support from Francis, Duke of Anjou, the brother of King Henry III of France. On September 29, 1580, the Staten Generaal (except for Zeeland and Holland) signed the Treaty of Plessis-les-Tours with the Duke of Anjou. The Duke would become the new ruler and "Protector of the Liberty of the Netherlands." This meant the Staten Generaal and William had to officially stop supporting the King of Spain.

On July 22, 1581, the Staten Generaal declared they no longer recognized Philip II of Spain as their ruler. This was the Act of Abjuration, a formal declaration of independence. This allowed the Duke of Anjou to help the rebels. He arrived on February 10, 1582, and William welcomed him in Flushing. On March 18, a Spaniard named Juan de Jáuregui tried to kill William in Antwerp. William was badly hurt but survived thanks to his wife Charlotte and sister Mary. While William recovered, Charlotte became exhausted from caring for him and died on May 5.

The Duke of Anjou was not very popular. Zeeland and Holland refused to recognize him as their ruler. William was criticized for his "French politics." When Anjou's French troops arrived in late 1582, William's plan seemed to work. Even the Duke of Parma worried the Dutch would gain the upper hand.

However, Anjou was unhappy with his limited power. He secretly decided to take Antwerp by force. The citizens were warned in time. They ambushed Anjou and his troops on January 18, 1583, in what is known as the "French Fury". Almost all of Anjou's men were killed. Anjou's position became impossible, and he left the country in June. His departure hurt William's reputation, but William still supported him. William was almost alone in this view and became politically isolated. Holland and Zeeland still kept him as their stadtholder. They tried to make him count of Holland and Zeeland, making him the official ruler.

In the middle of all this, William married for the fourth and final time on April 12, 1583. He married Louise de Coligny, a French Huguenot. She was the mother of Frederick Henry (1584–1647), William's fourth son. William, affectionately called "Father William," settled in the Prinsenhof in Delft. He lived like a simple Dutch citizen.

William's Assassination

Balthasar Gérard (born 1557) was a Catholic from Burgundy. He supported Philip II and saw William of Orange as a traitor. In 1581, Gérard learned that Philip II had declared William an outlaw. He promised a reward of 25,000 crowns for his assassination. Gérard decided to go to the Netherlands to kill William. He served in an army for two years, hoping to get close to William. This never happened, so Gérard left the army in 1584. He went to the Duke of Parma with his plan, but the Duke was not impressed.

In May 1584, Gérard presented himself to William as a French nobleman. He gave William a special seal. This seal would allow fake messages from a count to be made. William sent Gérard back to France to give the seal to his French allies.

Gérard returned in July. He had bought two pistols on his way back. On July 10, he had an appointment with William of Orange at his home in Delft, the Prinsenhof. That day, William was having dinner with a guest. After William left the dining room and walked downstairs, his guest heard Gérard shoot William in the chest. Gérard ran away but was caught before he could escape Delft. He was imprisoned and then executed.

William's Burial and Tomb

Members of the Nassau family were usually buried in Breda. But since that city was under Spanish control when William died, he was buried in the New Church in Delft. His first tomb was very simple. But in 1623, a new, grander one was built by Hendrik de Keyser and his son Pieter.

Since then, most members of the House of Orange-Nassau, including all Dutch monarchs, have been buried in the same church. His great-grandson William III and II, who became King of England, Scotland, and Ireland, was buried in Westminster Abbey.

William's Legacy

Succession and Family Ties

Philip William, William's oldest son from his first marriage, became the next Prince of Orange. However, Philip William had been a hostage in Spain for most of his life. So, his half-brother Maurice of Nassau was appointed Stadtholder and Captain-General. Maurice was a strong military leader. He won many battles against the Spanish.

Philip William died in Brussels in 1618. Maurice then became Prince of Orange. Maurice died in 1625. He had several sons, but he never married their mother. So, Frederick Henry, Maurice's half-brother, inherited the title. Frederick Henry was William's youngest son from his fourth marriage. He continued the fight against the Spanish. Frederick Henry died in 1647 and is buried with his father in Delft. The Netherlands became officially independent after the Peace of Westphalia in 1648.

Frederick Henry's son, William II of Orange, became stadtholder. His son, William III of Orange, also became King of England, Scotland, and Ireland in 1689. He died without children in 1702. He named his cousin Johan Willem Friso as his successor. The current royal family of the Netherlands is descended from William the Silent through his daughter's line.

William is considered a national hero in the Netherlands. He was the main leader and financer of the early Dutch revolt. He was born in Germany and usually spoke French.

Today, the Netherlands is a constitutional monarchy. King Willem-Alexander is the current head of state. He is a descendant of William of Orange. All stadtholders after William of Orange were his descendants or his brother's descendants.

Many Dutch national symbols come from William of Orange:

- He is the ancestor of the Dutch monarchy.

- The flag of the Netherlands (red, white, and blue) comes from William's flag. His flag was orange, white, and blue.

- The coat of arms of the Netherlands is based on William's. Its motto Je maintiendrai (French for "I will maintain") was also used by William.

- The national anthem of the Netherlands, the Wilhelmus, was originally a song to support William.

- The national color of the Netherlands is orange. It is used in many ways, like on Dutch athletes' clothing.

Other ways William of Orange is remembered:

- A statue of William the Silent was put up in 1928. It is at Rutgers University in New Jersey, USA. The university was founded by Dutch ministers. Students call the statue "Willie the Silent." It calls William the "Father of his Fatherland."

- In January 2008, the asteroid 12151 Oranje-Nassau was named after him.

Why "The Silent"?

There are different ideas about why William was called "William the Silent." The most common story is about a conversation he had with King Henry II of France.

No one knows for sure when or by whom the nickname "the Silent" was first used. It is often said that Cardinal de Granvelle called William "the silent one" around 1567. Both the nickname and the story first appear in a historical source from the early 1600s.

In the Netherlands, William is known as the Vader des Vaderlands, which means "Father of the Fatherland." The Dutch national anthem, the Wilhelmus, was written in his honor.

Family and Children

First Marriage

On July 6, 1551, 18-year-old William married Anna van Egmond en Buren. She was also 18 and inherited much wealth from her father. William gained the titles Lord of Egmond and Count of Buren. They had a happy marriage and three children. Their son Philip William would later become Prince. Anna died on March 24, 1558. William was very sad.

After Anna's death, William had a brief relationship with Eva Elincx. She was not from a noble family. They had a son, Justinus van Nassau. William officially recognized Justinus as his son and took care of his education. Justinus later became an admiral.

Second Marriage

On August 25, 1561, William married for the second time to Anna of Saxony. She was known to be difficult. William likely married her to gain more influence in parts of Germany. They had two sons and three daughters. One son died as a baby. Their other son, Maurice of Nassau, later became stadtholder but never married. Anna died after William ended their marriage and her own family imprisoned her.

Third Marriage

William married for the third time on June 12, 1575, to Charlotte de Bourbon-Monpensier. She was a former French nun and was popular with the public. They had six daughters. Their marriage seemed to be a loving one and was happy. Charlotte sadly died from exhaustion in 1582 while caring for William after an assassination attempt.

Fourth Marriage

William married for the fourth and final time on April 12, 1583. He married Louise de Coligny, a French Huguenot. She was the mother of Frederick Henry (1584–1647). Frederick Henry was William's fourth son. He was born only a few months before William's death. He was the only one of William's sons to have children and continue the family line. Frederick Henry's grandson, William III, became King of England, Scotland, and Ireland. However, he died without children, ending William the Silent's direct male line.

William's Children

| Name | Birth | Death | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| By Anna of Egmond (married 6 July 1551; died 24 March 1558) | |||

| Countess Maria of Nassau | 22 November 1553 | c. 23 July 1555 | Died as a baby. |

| Philip William, Prince of Orange and Count of Nassau |

19 December 1554 | 20 February 1618 | Married Eleonora of Bourbon-Condé. No children. |

| Countess Maria of Nassau | 7 February 1556 | 10 October 1616 | Married Count Philip of Hohenlohe-Neuenstein. |

| By Anna of Saxony (married 25 August 1561, marriage ended 22 March 1571; died 18 December 1577) | |||

| Countess Anna of Nassau | 31 October 1562 | Died at birth. | |

| Countess Anna of Nassau | 5 November 1563 | 13 June 1588 | Married Count Wilhelm Ludwig von Nassau-Dillenburg. |

| Count Maurice August Phillip of Nassau | 8 December 1564 | 3 March 1566 | Died as a baby. |

| Maurice of Nassau, Prince of Orange and Count of Nassau |

13 November 1567 | 23 April 1625 | Never married. |

| Countess Emilia of Nassau | 10 April 1569 | 6 March 1629 | Married Manuel de Portugal. They had 10 children. |

| By Charlotte of Bourbon (married 24 June 1575; died 5 May 1582) | |||

| Countess Louise Juliana of Nassau | 31 March 1576 | 15 March 1644 | Married Frederick IV, Elector Palatine. They had 8 children. Her son, Frederick V, was the grandfather of George I of Great Britain. |

| Countess Elisabeth of Nassau | 26 April 1577 | 3 September 1642 | Married to Henri de La Tour d'Auvergne. They had children. |

| Countess Catharina Belgica of Nassau | 31 July 1578 | 12 April 1648 | Married to Count Philip Louis II of Hanau-Münzenberg. |

| Countess Charlotte Flandrina of Nassau | 18 August 1579 | 16 April 1640 | Became a nun. She converted to Roman Catholicism. |

| Countess Charlotte Brabantina of Nassau | 17 September 1580 | August 1631 | Married Claude, Duc de Thouars. They had children. |

| Countess Emilia Antwerpiana of Nassau | 9 December 1581 | 28 September 1657 | Married Frederick Casimir, Count Palatine of Zweibrücken-Landsberg. |

| By Louise de Coligny (married 24 April 1583; died 13 November 1620) | |||

| Frederick Henry, Prince of Orange and Count of Nassau |

29 January 1584 | 14 March 1647 | Married to Countess Amalia of Solms-Braunfels. He was the father of William II and grandfather of William III, King of England, Scotland, Ireland and Stadtholder of the Netherlands. |

Between his first and second marriages, William had a son with Eva Elincx. His name was Justinus van Nassau (1559–1631). William recognized him as his son. Justinus later married Anne, Baronesse de Mérode, and they had three children.

Titles and Coats of Arms

A nobleman's power came from owning land and important positions. William was the Prince of Orange and a Knight of the Golden Fleece. He also held other lands and titles, often under the King of France or the Habsburg rulers. As a holder of these lands, he was also:

- Marquis of Veere and Vlissingen

- Count of Nassau-Dillenburg, Katzenelnbogen, and Vianden

- Viscount of Antwerp

- Baron of Breda, Lands of Cuijk, City of Grave, Diest, Herstal, Warneton, Beilstein, Arlay, and Nozeroy; Lord of Dasburg, Geertruidenberg, Hooge en Lage Zwaluwe, Klundert, Montfort, Naaldwijk, Niervaart, Polanen, Steenbergen, Willemstad, Bütgenbach, Sankt Vith, and Besançon

William used two main coats of arms during his life. The first one was his family's original arms from Nassau. The second one he used for most of his life. He started using it after he became Prince of Orange when his cousin René of Châlon died. He added the arms of Châlon-Arlay (the Princes of Orange) onto his father's arms.

In 1582, William bought the marquisate of Veere and Vlissingen. This land had belonged to Philip II. William bought it because it gave him two more votes in the States of Zeeland. He controlled the governments of these two towns, so he could choose their leaders. This made William the most powerful member of the States of Zeeland. It was a smaller version of the countship of Zeeland (and Holland) that was promised to William. It became a strong political base for his family in the future. William then added the shield of Veere and Buren to his arms. This shows how coats of arms were used to represent political power and William's growing influence.

See also

In Spanish: Guillermo de Orange para niños

In Spanish: Guillermo de Orange para niños

Images for kids

-

The triumphal entry of the Prince of Orange in Brussels. Print from The Wars of Nassau by Willem Baudartius.