Beeldenstorm facts for kids

The Beeldenstorm (pronounced [ˈbeːldə(n)ˌstɔr(ə)m]) in Dutch and Bildersturm [ˈbɪldɐˌʃtʊʁm] in German mean 'attack on images or statues'. These terms describe times in the 16th century when religious images were destroyed in Europe. In English, this period is called the Great Iconoclasm or Iconoclastic Fury. In French, it is the Furie iconoclaste.

During these events, Catholic art and church decorations were smashed. This was done by large groups of Calvinist Protestants. It was part of the Protestant Reformation. Most of the destruction happened in churches and public places.

The Dutch term "Beeldenstorm" usually refers to the attacks in the summer of 1566. These attacks quickly spread through the Low Countries (modern-day Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg). Similar events happened in other parts of Europe. This included Switzerland and the Holy Roman Empire between 1522 and 1566. Famous examples include Zürich (1523), Copenhagen (1530), Münster (1534), Geneva (1535), and Augsburg (1537).

In England, images were removed by the government and by people starting in 1535. In Scotland, this began in 1559. France also saw several outbreaks during the French Wars of Religion from 1560.

Contents

Why the Beeldenstorm Happened

Unofficial attacks on church art by Huguenot Calvinists started in France in 1560. Unlike the Low Countries, Catholic groups often fought back there. In England, much destruction was ordered by the government. In Northern Europe, Calvinists removed images from churches. This sometimes led to fights with Lutherans in Germany.

In Germany, Switzerland, and England, everyone in a city or kingdom had to become Protestant. People who stayed Catholic faced problems or were forced to leave. The Low Countries were ruled by Philip II of Spain. He was a strong Catholic and wanted to protect the Catholic Church. He tried to stop Protestantism through his governor, Margaret of Parma. She was the daughter of Emperor Charles V and was more open to finding a middle ground.

Protestants were a small part of the population in the Low Countries. But many nobles and rich people were Protestant. The Catholic Church had lost the trust of many people. There was also a lot of anger against the clergy.

The Low Countries were very rich. But some people were unhappy about money matters. There had also been a bad harvest and a cold winter. However, historians now think these problems were not the main cause of the Beeldenstorm.

The Beeldenstorm grew from a change in how Protestants acted around 1560. They became more open about their faith, even though it was against the law. They would interrupt Catholic sermons. They also rescued Protestant prisoners from jail. These prisoners often fled to France or England.

Protestant ideas spread through "field sermons" (Dutch: hagepreken). These were open-air sermons held outside towns. This meant they were outside the control of town officials. The first one was near Hondschoote in what is now French Flanders. This was close to where the attacks later started. The first armed sermon was near Boeschepe on July 12, 1562. This was two months after religious war started again nearby in France.

These outdoor sermons, often by Anabaptist or Mennonite preachers, spread across the country. They attracted huge crowds. In many places, these sermons happened just before the iconoclastic attacks of August 1566. People were still punished for heresy, especially in the south. But by 1565, the authorities realized that punishment was not working. Protestants became more confident. On July 22, 1566, officials warned that "scandalous pillage of churches" was about to happen.

Attacks in the Low Countries in 1566

On August 10, 1566, the feast day of Saint Lawrence, a crowd attacked the chapel of the Sint-Laurensklooster near Steenvoorde. Some think the rioters linked Saint Lawrence to Philip II. Philip's palace, the Escorial near Madrid, was dedicated to Lawrence.

The attacks quickly spread north. They destroyed not only images but also decorations and fittings in churches. Other church property was also damaged. However, few people were killed. This was different from similar outbreaks in France, where clergy and iconoclasts often died.

The attacks reached Antwerp, a major trading city, on August 20. On August 22, they reached Ghent. There, the cathedral, eight churches, twenty-five monasteries, ten hospitals, and seven chapels were destroyed. From Ghent, the attacks spread east and north. They reached Amsterdam by August 23. They continued in the far north and east into October. Most main towns were attacked in August. Valenciennes was the most southern town attacked. In the east, Maastricht (September 20) and Venlo (October 5) saw attacks. But generally, the attacks were mostly in western and northern areas. Over 400 churches were attacked in Flanders alone.

Richard Clough, an English Protestant merchant in Antwerp, saw the destruction. He wrote that "all the churches... utterly defaced... no kind of thing left whole... broken and utterly destroyed." He was amazed it was done by "so few folks." The Church of Our Lady in Antwerp (shown at the top of the article) "looked like a hell, with above 10,000 torches burning." He described "such a noise as if heaven and earth had got together, with falling of images and beating down of costly works." He said the damage was so great "that a man could not well pass through the church." Organs were also destroyed.

Nicholas Sanders, an English Catholic professor, described the destruction in the same church: "... these new followers threw down the sculpted and defaced the painted images. Not only of Our Lady but of all others in the town. They tore curtains, smashed brass and stone carvings, broke altars, ruined clothes and sacred cloths. They took or broke chalices and vestments. They pulled up brass from gravestones. They did not spare the glass and seats around the church pillars. ... They burned and tore not only all Church books, but also destroyed whole libraries of books of all subjects and languages. Even the Holy Scriptures and writings of early Church leaders. They also tore maps and charts."

Many other sources confirm these details. Accounts from eyewitnesses and court records show that the attacks often felt like a carnival. People mocked the images and church items as they destroyed them.

The destruction often included searching the priest's house. Sometimes, private homes thought to hide church goods were also searched. There was much looting of household items from clergy homes and monasteries. Some people in the crowd also robbed women's jewelry on the street. After images were smashed, people ate and drank beer, bread, butter, and cheese. Women took food and items for their homes.

There are many stories of things being turned upside down. The church sometimes represented the whole social order. Children sometimes joined in with excitement. Street games afterwards became play battles between "papists" (Catholics) and "beggars" (Protestants). One child was killed in Amsterdam by a stone thrown in such a game. In another city, the iconoclasts waited for the bell marking the start of the workday before they began.

Tombs and memorials of important families and nobles were damaged or destroyed in some places. But public buildings like town halls and noble palaces were not attacked. In Ghent, a memorial to Charles V's sister Isabel was left untouched. But a statue of Charles V and the Virgin Mary in the street was destroyed.

These actions caused arguments among Protestants. Some tried to blame Catholic agents for causing trouble. It became clear that "the more popular elements of the dissident movement were out of control." Protestant ministers returning from exile played a big role. Some rich Protestants were thought to have hired people to do the destruction, especially in Antwerp.

In some rural areas, groups of iconoclasts moved between village churches and monasteries for days. In other places, large crowds were involved. Sometimes, nobles helped by ordering churches on their lands to be cleared. Local officials often disagreed with the attacks but could not stop them. In many towns, the archer's guild, which helped keep order, did nothing against the crowds.

In 1566, Protestantism was stronger in the south (modern Belgium) than in the north (modern Netherlands). Iconoclasm in the north started later, after news from Antwerp arrived. Local authorities in some northern towns resisted more successfully. But the attacks still happened in most places. Again, important laymen often led the way. In many places, people falsely claimed to have official orders to destroy images. By the end, some northern towns removed images by official order. This was probably to prevent mob violence.

Records of later trials show that many different people were involved. They included craftsmen and small traders, especially in the textile business. Also, various low-level church employees took part. Their wealth was usually "modest at best."

"Stille beeldenstorm" of 1581 in Antwerp

Antwerp had another period of iconoclasm in 1581. This happened after a Calvinist city council was elected. This council removed Catholic officials from the city's clergy and guilds. This event is called the "quiet" or "stille" beeldenstorm. Images were removed by the churches and guilds themselves. Some images were sold instead of destroyed. But most seem to have been lost. In 1584, Antwerp was attacked by the Duke of Parma's Spanish army. It fell a year later.

Loss of Art

In 1566, people rarely thought about the artistic value of the items. But families sometimes protected the church monuments of their ancestors. In Delft, the leaders of the painters' Guild of Saint Luke saved an altarpiece by Maarten van Heemskerck. The guild had ordered it only 15 years earlier.

The van Eycks' Ghent Altarpiece was very famous. It was a top example of Early Netherlandish painting. It was already a major tourist attraction and had just been restored in 1550. It was saved by taking it apart and hiding it in the cathedral tower. A first attack on August 19 was stopped by a few guards. Two days later, a larger attack happened at night. The iconoclasts used a tree trunk as a battering ram. They broke through the doors.

By then, the panels had been removed from the frame and hidden. They were with the guards on the narrow spiral staircase up the tower. A locked door was at ground level. The panels were not found. The crowd left after destroying other things. The panels were then moved to the town hall. They were only put back on display in 1569. By then, the fancy frame was gone. The artistic and literary losses were described by Marcus van Vaernewyck in his journal. The original journal is still in the Ghent University Library.

Despite guards, two of the three main churches in Leiden were attacked. In the Pieterskerk, the choirbooks and an altarpiece by Lucas van Leyden were saved. In the Oude Kerk in Amsterdam, an altarpiece was lost. It had a main panel by Jan van Scorel and side panels by Maarten van Heemskerck. Many important works by painters like Pieter Aertsen were destroyed. This makes it harder to understand the art history of that time. An altarpiece in Culemborg was ordered in 1557. It was destroyed in 1566. In 1570, the painter was asked to make a copy. But the new work was only there for five years. It was removed when the town officially became Calvinist.

What Happened Next

On August 23, Margaret of Parma, the ruler of the Habsburg Netherlands, made an agreement. Her capital, Brussels, was not affected by the attacks. She agreed with a group of Protestant nobles called the "Compromise" or Geuzen ("Beggars"). This agreement gave freedom of religion. In return, Catholics could worship safely, and the violence would stop.

However, the "iconoclastic fury began an almost uninterrupted series of skirmishes, campaigns, plunder, pirate-raids, and other acts of violence." Not all areas suffered the same. But almost none were left unharmed.

Many important Protestants were worried by the violence. Some nobles started to support the government. The agreement's unclear terms led to more problems. William of Orange tried to find a wider solution in Antwerp. But he failed. The unrest continued. This episode helped cause the Dutch Revolt, which began two years later.

On August 29, 1566, Margaret wrote to Philip. She said that half the people were heretics. She claimed over 200,000 people were fighting her rule. Philip decided to send the Duke of Alba with an army. Philip wanted to lead them himself. But he stayed in Spain because his son, Carlos, Prince of Asturias, was becoming mentally ill. When Alba arrived the next year, he replaced Margaret as governor. His harsh actions, including executing many iconoclasts, made things worse.

Antwerp was Europe's largest financial and trading center. It handled most of England's cloth exports. The disturbances made people fear that Antwerp's position was at risk. Sir Thomas Gresham, an English financier, was in Antwerp during the attacks. He wrote to William Cecil, Elizabeth's chief minister. He said he "liked none of their proceedings" and "apprehended great mischief." He urged the English government to "consider some other realm and place" for trade. This message helped shape future events.

The English had found Antwerp's money market short of funds earlier that year. Now they used Cologne and Augsburg as well. As events unfolded, the English found that lenders were not pressing for repayments. This was probably because lenders were happy to keep their money loaned to a safe borrower abroad. The Dutch Revolt, which included a blockade of the River Scheldt from 1585, finally destroyed Antwerp as a major trading center.

In many places, Calvinist preachers tried to take over the damaged buildings. But they were usually stopped after the attacks. In the months that followed, there were talks in many cities. William of Orange and others tried to give certain churches to local Protestants. But these talks mostly failed. Margaret's government rejected them. She had already had an earlier compromise overruled by Philip.

Instead, many Calvinist "temples" were built or changed. But none of these remained in use the next year. Their designs, which were like early Swiss and Scottish Calvinist churches, are mostly unknown now.

Once the revolt truly began, churches were cleared many more times. Some clearings were still unofficial. But as cities became officially Protestant, they were increasingly done by official order. An example is the Amsterdam Alteratie ("Alteration") of 1578. Altars, which Calvinists strongly disliked, were usually removed completely. In some large churches, like Utrecht Cathedral, large tomb monuments were put where altars stood. This made it harder to put the altars back if politics changed.

As the Eighty Years' War ended, old Catholic churches in Protestant areas were taken over by the new established faith. This was the Calvinist Dutch Reformed Church. Other religious groups had to find their own buildings.

The empty state of churches left in Catholic hands led to a big effort to restock them with Catholic art. This helped the growth of Northern Mannerism and later Flemish Baroque painting. Many Gothic churches were given Baroque makeovers. In the north, which was now strongly Protestant, religious art mostly disappeared. Dutch Golden Age painting focused on everyday subjects. These included genre painting (scenes of daily life), landscape art, and still-lifes. The results might have surprised the Protestant ministers who started the movement. One expert says this was a huge change in art's purpose. It was when our modern idea of art first began to form.

Images for kids

-

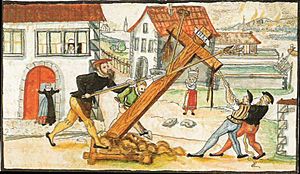

Woodcut from 1563 from Foxe's Book of Martyrs.

See also

In Spanish: Beeldenstorm para niños

In Spanish: Beeldenstorm para niños

- Catacomb saints

- Destruction of cultural heritage by the Islamic State

- The Reformation and art

- European wars of religion

- History of Flanders, History of the Netherlands

- Iconophobia#Iconophobia and the English Reformation

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |