History of the Netherlands facts for kids

The history of the Netherlands is a long story about people living together in the river deltas along the North Sea coast. It goes back thousands of years, long before the modern Kingdom of the Netherlands was formed in 1815.

For about 400 years, this area was a border region of the Roman Empire. When the Roman Empire declined, three main Germanic peoples settled here: the Frisians in the north, the Low Saxons in the northeast, and the Franks in the south. Around 800 AD, the Frankish Carolingian empire, led by Charlemagne, brought the area together again. Later, it became part of the Holy Roman Empire, but local lords like those from Brabant, Holland, and Guelders ruled their own changing territories.

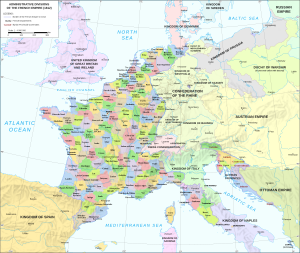

By 1433, the Duke of Burgundy took control of most of these lands, forming the Burgundian Netherlands. This included what is now the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, and parts of France. When the Catholic kings of Spain, who inherited these lands, took strong actions against Protestantism, it led to the Dutch Revolt. This revolt caused the Netherlands to split in 1581. The southern part became the "Spanish Netherlands" (modern Belgium and Luxembourg), and the northern part became the "United Provinces" (or "Dutch Republic)". This northern part, which spoke Dutch and was mostly Protestant, is the ancestor of today's Netherlands.

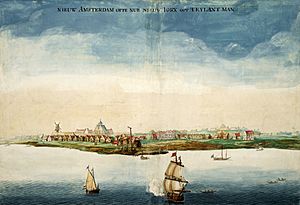

The Dutch Golden Age, around 1667, was a time of great success in trade, industry, and science. A rich worldwide Dutch empire grew, and the Dutch East India Company became a very important trading company. However, in the 18th century, the Netherlands' power and wealth decreased. Wars with stronger neighbors like the British and French weakened it. The English even took the North American colony of New Amsterdam and renamed it "New York." After the French Revolution, a pro-French government called the Batavian Republic was set up in 1795. Napoleon later made it a satellite state, the Kingdom of Holland, and then part of France.

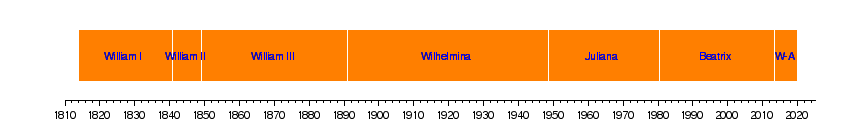

After Napoleon's defeat in 1813–1815, a larger "United Kingdom of the Netherlands" was created. The House of Orange-Nassau became its monarchs, also ruling Belgium and Luxembourg. But when the King tried to impose unpopular changes on Belgium, it left the kingdom in 1830. New borders were agreed upon in 1839. After a period of conservative rule, the country became a parliamentary democracy with a constitutional monarch in 1848. Modern-day Luxembourg became officially independent in 1839, but shared a ruler with the Netherlands until 1890.

The Netherlands stayed neutral during the First World War. But in the Second World War, Nazi Germany invaded and occupied it. The Nazis, with help from some locals, rounded up and killed almost all Jewish people in the country. When the Dutch resistance grew, the Nazis cut off food supplies, causing a terrible famine in 1944–1945. In 1942, Japan conquered the Dutch East Indies. After the war, Indonesia proclaimed its independence from the Netherlands in 1945, followed by Suriname in 1975. The years after the war saw fast economic recovery, helped by the American Marshall Plan. A welfare state was introduced during a time of peace and prosperity. The Netherlands formed a new economic group with Belgium and Luxembourg called the Benelux. All three became founding members of the European Union and NATO. Today, the Dutch economy is very strong and closely linked to Germany's. The Netherlands adopted the euro currency on January 1, 2002.

| History of the Low Countries | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frisii | Belgae | |||||||

| Cana- nefates |

Chamavi, Tubantes |

Gallia Belgica (55 BC – 5th c. AD) Germania Inferior (83 – 5th c.) |

||||||

| Salian Franks | Batavi | |||||||

| unpopulated (4th–5th c.) |

Saxons | Salian Franks (4th–5th c.) |

||||||

| Frisian Kingdom (6th c.–734) |

Frankish Kingdom (481–843)—Carolingian Empire (800–843) | |||||||

| Austrasia (511–687) | ||||||||

| Middle Francia (843–855) | West Francia (843–) |

|||||||

| Kingdom of Lotharingia (855– 959) Duchy of Lower Lorraine (959–) |

||||||||

| Frisia | ||||||||

Frisian Freedom (11–16th century) |

County of Holland (880–1432) |

Bishopric of Utrecht (695–1456) |

Duchy of Brabant (1183–1430) Duchy of Guelders (1046–1543) |

County of Flanders (862–1384) |

County of Hainaut (1071–1432) County of Namur (981–1421) |

P.-Bish. of Liège (980–1794) |

Duchy of Luxem- bourg (1059–1443) |

|

Burgundian Netherlands (1384–1482) |

||||||||

Habsburg Netherlands (1482–1795) (Seventeen Provinces after 1543) |

||||||||

Dutch Republic (1581–1795) |

Spanish Netherlands (1556–1714) |

|||||||

Austrian Netherlands (1714–1795) |

||||||||

United States of Belgium (1790) |

R. Liège (1789–'91) |

|||||||

Batavian Republic (1795–1806) Kingdom of Holland (1806–1810) |

associated with French First Republic (1795–1804) part of First French Empire (1804–1815) |

|||||||

Princip. of the Netherlands (1813–1815) |

||||||||

| United Kingdom of the Netherlands (1815–1830) | Gr D. L. (1815–) |

|||||||

Kingdom of the Netherlands (1839–) |

Kingdom of Belgium (1830–) |

|||||||

| Gr D. of Luxem- bourg (1890–) |

||||||||

Contents

- Ancient Times: Before the Romans (before 57 BC)

- Roman Rule (57 BC – 410 AD)

- Early Middle Ages (411–1000)

- High and Late Middle Ages (1000–1433)

- Burgundian and Habsburg Rule (1433–1567)

- The Eighty Years' War (1568–1648)

- The Golden Age (1600s)

- The Dutch Empire

- Dutch Republic: Regents and Stadholders (1649–1784)

- The French-Batavian Period (1785–1815)

- United Kingdom of the Netherlands (1815–1839)

- Democratic and Industrial Development (1840–1900)

- 1900 to 1940

- The Second World War (1939–1945)

- Prosperity and European Unity (1945–Present)

- Images for kids

- See also

Ancient Times: Before the Romans (before 57 BC)

During the last ice age, the Netherlands was a cold, open land with few plants. People lived as hunter-gatherers, finding food and shelter. The Swifterbant culture, appearing around 5600 BC, were hunter-gatherers who lived near rivers and open water. They were similar to people in southern Scandinavia.

Around 5000 BC, farming arrived in areas near the Netherlands with the Linear Pottery culture. These farmers came from Central Europe. Their farms were only in southern Limburg for a short time. However, some coastal people started using pottery and raising animals between 4800 BC and 4500 BC. By 4000 BC, the Funnelbeaker culture brought permanent farming to the region. This culture stretched from Denmark to the northern Netherlands.

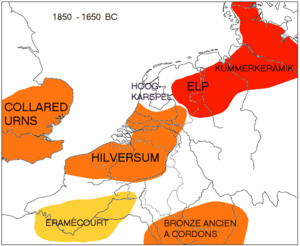

Around 2950 BCE, the Corded Ware culture spread across much of northern and central Europe. This brought indoeuropean languages and early metal tools. The Elp culture in the north and the Hilversum culture in the south developed during the Bronze Age.

The Iron Age brought more wealth to the people in the Netherlands. Iron ore was available everywhere. Metalworkers traveled between small villages, making tools like axes, knives, and swords. Before the Romans arrived, the Harpstedt culture grew in the north. This group split into early Frisians and early Saxons in the north, and Franks in the south.

Roman Rule (57 BC – 410 AD)

During his wars in Gaul, Julius Caesar conquered all of Gaul for Rome. This included the Netherlands south of the Rhine river. He wrote about his experiences, giving us the first written accounts of the region. Caesar mentioned the Menapii living in the river delta and the Eburones to their southeast. He called the land between the Rhine and Waal "the island of the Batavi."

Roman rule lasted 450 years and greatly changed the region. The Rhine was a military border, often unstable due to attacks. Rome recruited soldiers from both sides of the river. Local tribes were respected soldiers in the Roman army, often serving as cavalry. Trade grew after Rome conquered Gaul. However, there were problems, like the Romans taking young Batavians as slaves. This led to the Batavian rebellion in 69 AD, where rebels burned Roman forts. The Romans defeated the rebels in 70 AD.

Later, a Frankish identity appeared in the lower and middle Rhine valley. The Frisii likely disappeared from the northern Netherlands around 296 AD, possibly due to coastal flooding or being moved by the Romans.

Early Middle Ages (411–1000)

The Frisians and Franks

As the climate improved, many Germanic people moved into the area from the east. This was called the "Migration Period." The northern Netherlands received new settlers, mostly Saxons, but also Angles and Jutes. Many of these people moved on to England, becoming the Anglo-Saxons. Those who stayed in the northern Netherlands became known as "Frisians." Their language was very similar to Old English. By the end of the 6th century, Frisian land in the northern Netherlands had expanded west to the North Sea coast. By the 7th century, it reached south to Dorestad. This large Frisian area was sometimes called Frisia Magna.

In the 7th and 8th centuries, this area was known as the Frisian Kingdom. Its power center was in Utrecht. Dorestad was the largest trading settlement in northwestern Europe. It was a busy trading place, three kilometers long, near where the Rhine and Lek rivers split. It was known for trading wine and had its own mint for coins.

After the Roman government collapsed, the Franks expanded their lands. By the 490s, Clovis I had conquered and united all Frankish lands west of the Meuse river, including the southern Netherlands. This area became part of Austrasia. Many Frankish people stayed in the north (southern Netherlands, Flanders). Their language, Old Frankish, developed into Old Dutch by the 9th century. The Franks had important political and trading centers in the Maas and Rhine areas, like Nijmegen and Maastricht.

The Rise of the Dutch Language and Christianity

The language that became Old Dutch likely came from the Salian Franks. It was closely related to Old Saxon, Old English, and Old Frisian. Old Dutch changed into Middle Dutch around 1150.

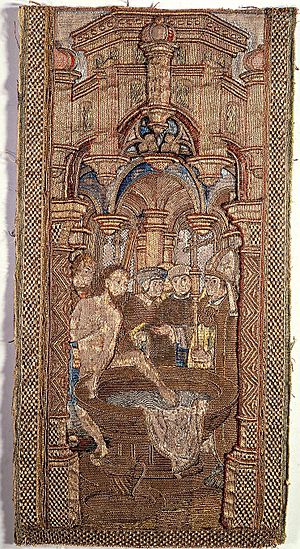

Christianity, which arrived with the Romans, did not completely disappear. The Franks became Christians after their king, Clovis I, converted around 496. Christianity spread to the north after the Franks conquered Friesland. Missionaries like Willibrord and Boniface helped convert the Frankish and Frisian people by the 8th century.

In the early 8th century, the Frisians and Franks fought a series of wars. The Frankish Empire eventually took over Frisia. In 734, at the Battle of the Boarn, the Franks defeated the Frisians in the Netherlands. By 785, Charlemagne defeated the last Frisian leader, taking control of the whole area.

The Netherlands was part of Charlemagne's Frankish empire. Cities like Aachen, Maastricht, Liège, and Nijmegen were important centers of Carolingian culture. In 843, the Frankish empire was divided into three parts. Most of what is now the Netherlands became part of Middle Francia, which later became Lotharingia. In 870, Lotharingia became part of East Francia, which became the Holy Roman Empire in 962.

Viking Raids

In the 9th and 10th centuries, Vikings attacked the towns along the coast and rivers of the Low Countries. While Vikings did not settle in large numbers, they set up long-term bases. The trading center of Dorestad is thought to have declined after Viking raids from 834 to 863. However, there is little archaeological proof of this.

One important Viking leader was Rorik of Dorestad. Around 850, he was recognized as ruler of most of Friesland. Viking raids continued, but local nobles gained power by resisting them. By 885, Viking rule in Frisia ended. Viking attacks continued until the early 11th century, targeting towns like Tiel and Utrecht.

High and Late Middle Ages (1000–1433)

Becoming Part of the Holy Roman Empire

German kings and emperors ruled the Netherlands in the 10th and 11th centuries. They were helped by the Dukes of Lotharingia and the bishops of Utrecht and Liège. Germany was called the Holy Roman Empire after King Otto the Great became emperor. The Dutch city of Nijmegen was an important place for the German emperors.

Political Divisions and Local Rulers

The Holy Roman Empire could not keep political unity. Local rulers turned their counties and duchies into their own kingdoms. They felt little duty to the emperor, who only ruled large parts of the nation in name. Much of the Netherlands was governed by the Count of Holland, the Duke of Gelre, the Duke of Brabant, and the Bishop of Utrecht. Friesland and Groningen in the north remained independent.

These different states were almost always at war. Gelre and Holland fought for control of Utrecht. Utrecht, which once ruled half of today's Netherlands, lost power. Holland tried to take over Zeeland and Friesland, but failed.

The Frisians and the Rise of Holland

The people in the area now called Holland originally spoke a Frisian language. This area was known as "West Friesland." Over time, people in Holland adopted the Frankish language and feudal system, spreading this new "Hollandic" identity north.

The rest of Friesland in the north stayed independent. They had their own rules and disliked the feudal system. They saw themselves as allies of Switzerland, with the cry "better dead than a slave." They lost their independence in 1498 when they were defeated by German soldiers.

The center of power in these independent territories was the County of Holland. It was given to the Danish chieftain Rorik in 862. The region around modern Haarlem grew quickly under Rorik's descendants. By the early 11th century, Dirk III, Count of Holland was collecting tolls on the Meuse river. He could even resist military attacks from his overlord.

In 1083, the name "Holland" first appeared. Holland's influence grew over the next two centuries. The counts of Holland conquered most of Zeeland. By 1289, Count Floris V was able to take control of the Frisians in West Friesland (northern North Holland).

Growth of Towns and Trade

Around 1000 CE, new farming methods led to more food production. The economy grew quickly, allowing people to farm more land or become traders.

After 1200 CE, people started draining swampy areas and controlling floods much more. This created more farmland and led to population growth. Holland grew more than other regions. From the 13th century on, managing water was crucial. Drainage boards were set up, and "dike counts" handled water, taxes, policing, and legal matters. By the end of the 13th century, Holland became the most powerful northern region.

The southern Low Countries remained very populated and developed. They were among the most urbanized areas in Europe. The large rivers flowing east-west created a natural barrier between north and south. This division meant the counts of Holland became politically important in the north.

Guilds were formed, and markets grew as production went beyond local needs. Money made trading much easier. Towns grew, and new ones appeared around monasteries and castles. A middle class of merchants began to develop. Trade and town growth increased with the population.

The Crusades were popular and drew many to fight in the Holy Land. At home, there was relative peace. Viking attacks had stopped. Both the Crusades and peace at home helped trade and commerce grow.

Cities like Bruges and Antwerp (in Flanders) grew and became very important. As cities gained wealth, they bought special rights from their rulers, like the right to govern themselves and make laws. This meant the richest cities became almost independent republics.

Hook and Cod Wars

The Hook and Cod Wars were a series of fights in the County of Holland between 1350 and 1490. These wars were mostly about who would be the count of Holland. Some historians say the real reason was a power struggle between city traders and the ruling nobles.

The Cod group was generally made up of the more modern cities of Holland. The Hook group mostly consisted of conservative noblemen. Important figures in this long conflict included Jacqueline, Countess of Hainaut.

The Duke Philip the Good of Burgundy took over Holland in a strange way. Leading noblemen in Holland invited him to conquer Holland, even though he had no historical claim to it. Some historians believe the ruling class in Holland wanted Holland to join the rich Flemish economic system.

Burgundian and Habsburg Rule (1433–1567)

The Burgundian Period

Most of what is now the Netherlands and Belgium was eventually united by the Duke of Burgundy, Philip the Good (1396-1467). Before this, Dutch people identified with their town, local duchy, or as subjects of the Holy Roman Empire. These lands were ruled together by the House of Valois-Burgundy.

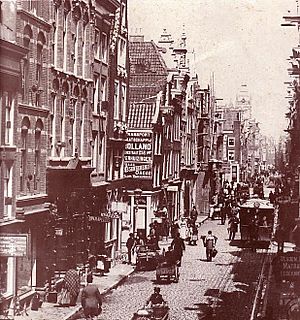

Trade grew quickly, especially in shipping. The new rulers protected Dutch trading interests. Amsterdam grew and became the main European port for grain from the Baltic Sea in the 15th century. This trade was vital because the region could no longer grow enough food for itself.

Habsburg Rule from Spain

Charles V (1500–1558) was born in Ghent and spoke French. He expanded the Burgundian territory, adding Utrecht, Groningen, and Guelders to create the Seventeen Provinces. These lands were technically part of France or the Holy Roman Empire. France gave up its claim on Flanders in 1528.

From 1515 to 1523, Charles's government faced a rebellion by Frisian peasants. Gelre also tried to create its own state. The dukes of Burgundy had gained control of the Seventeen Provinces (now the Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg) through marriages, purchases, and wars. These lands came under the control of the Habsburg family.

Charles became ruler in 1506, but in 1515, he left to become king of Spain and later Holy Roman Emperor. Spanish officials, sent by Charles, ignored local traditions and Dutch nobles. This caused anti-Spanish feelings, leading to the Dutch Revolt. Charles, a strong Catholic, wanted to stop Protestantism. Unrest began in the south, especially in Antwerp. The Netherlands was a very rich part of the Spanish realm.

In 1548, Charles made the Netherlands a special entity within the Holy Roman Empire. A year later, the Pragmatic Sanction of 1549 stated that the Seventeen Provinces could only be passed on to his heirs as one whole unit.

The Reformation and Growing Conflict

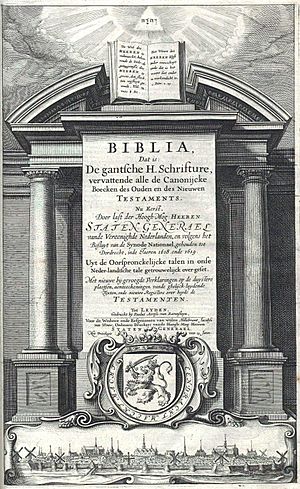

In the 16th century, the Protestant Reformation spread quickly in northern Europe, especially Lutheranism and Calvinism. Dutch Protestants were tolerated by local authorities. By the 1560s, Protestants were a significant group, though still a minority. In a trading society, freedom and tolerance were important. However, Catholic rulers like Charles V and Philip II wanted to defeat Protestantism, seeing it as a threat.

Dutch Protestants believed their faith was morally better than the luxurious habits of the Catholic Church leaders. The rulers' harsh punishments led to more complaints in the Netherlands. In the second half of the century, the situation got worse. Philip sent troops to crush the rebellion and make the Netherlands Catholic again.

The first wave of the Reformation, Lutheranism, was suppressed. The second wave, Anabaptism, was popular among farmers. Anabaptists were very radical and believed the end of the world was near. They created new communities, causing chaos. The third wave, Calvinism, arrived in the 1540s and attracted both rich and common people. The Spanish responded with harsh persecution and the Inquisition of the Netherlands.

Calvinists rebelled. First, there was the iconoclasm in 1566, where statues of saints in churches were destroyed. In 1566, William the Silent, a Calvinist, started the Eighty Years' War to free all Dutch people from Catholic Spain. William's patience and tolerance helped keep the Dutch united. The provinces of Holland and Zeeland, mostly Calvinist by 1572, accepted William's rule. Other states remained Catholic.

Leading up to War

The Netherlands was a valuable part of the Spanish Empire. The Treaty of Cateau-Cambresis in 1559 ended wars between France and Spain, allowing Spain to move its army. With peace, there was no longer a need for Spanish troops in the Netherlands.

The Dutch economy was booming. Fishing, especially for herring, was huge. The Dutch sold furniture and wool products to Spain and England. The Netherlands was becoming one of the richest places in the world. Its population reached 3 million in 1560, with 25 cities having over 10,000 people. Antwerp was a major trading and financial center with 100,000 people. Spain could not afford to lose this rich land or let it become Protestant. This led to 80 years of war.

Philip II, a strong Catholic, was upset by the spread of Protestantism in the Netherlands. His attempts to force Catholicism and centralize government, law, and taxes made him unpopular. This led to a revolt. Fernando Alvarez de Toledo, Duke of Alba, was sent with a Spanish army in 1567 to punish the Dutch.

The Duke of Alba arrested and executed nobles like Lamoral, Count of Egmont and Philippe de Montmorency, Count of Horn. William the Silent fled to Germany. Alba then canceled all agreements with Protestants and brought in the Inquisition.

The Eighty Years' War (1568–1648)

The Dutch War for Independence from Spain is called the Eighty Years' War (1568–1648). The first 50 years (1568–1618) were mainly between Spain and the Netherlands. The last 30 years (1618–1648) were part of the larger Thirty Years' War in Europe. The seven rebellious provinces of the Netherlands united in the Union of Utrecht in 1579, forming the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands. The Act of Abjuration on July 26, 1581, was their official declaration of independence from the Spanish king.

William the Silent led the Dutch during the first part of the war. The Spanish troops had early successes. They massacred citizens in Zutphen and Naarden in 1572. Haarlem was besieged for seven months. Maastricht was attacked and destroyed twice.

Governor-General Alexander Farnese offered good surrender terms to cities: no massacres, no looting, old city rights kept, full pardon, and a gradual return to the Catholic Church. The Catholics in the south and east supported the Spanish. Farnese recaptured Antwerp and most of what became Belgium. Many Flemish people, especially from Antwerp, fled to Holland. His campaign gave Catholics control of the southern Low Countries.

The war continued for another 50 years, but the main fighting was over. The Peace of Westphalia in 1648 confirmed the independence of the United Provinces from Spain. The Dutch people had started to form a national identity since the 15th century. They officially remained part of the Holy Roman Empire until 1648.

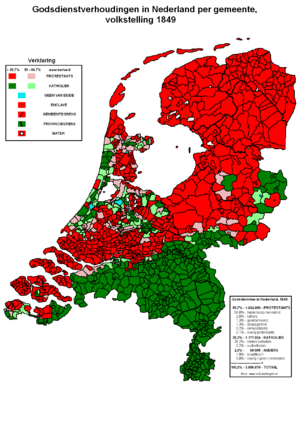

Catholics in the Netherlands became a minority group. After 1572, they made a comeback, setting up churches and sending missionaries. Catholic numbers stabilized at about one-third of the population in the Netherlands. They were strongest in the southeast.

The Golden Age (1600s)

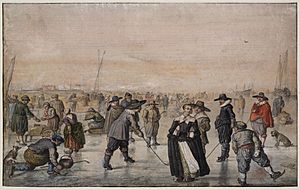

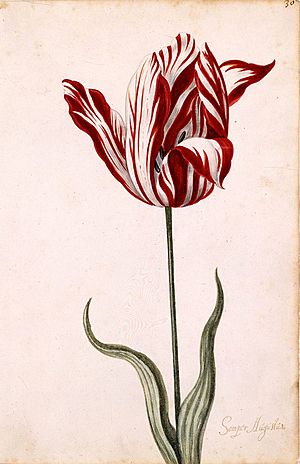

During the Eighty Years' War, the Dutch provinces became the most important trading center in Northern Europe. The 17th and 18th centuries were a time of great success in trade, industry, arts, and sciences. The Dutch were arguably the wealthiest and most scientifically advanced European nation. This new, Calvinist nation thrived culturally and economically. This period is called the Golden Age of the Netherlands. Even though there was a financial bubble in tulip trade in 1637, the economy quickly recovered.

The invention of the sawmill allowed for building a huge fleet of ships for worldwide trade and defense. Industries like shipyards and sugar refineries also grew.

The Dutch, known for their sailing skills and mapmaking, became leaders in world trade. In 1602, the Dutch East India Company (VOC) was founded. It was the first-ever multinational corporation, financed by shares on the first modern stock exchange. It became the world's largest business in the 17th century. The Bank of Amsterdam was set up in 1609, a very early form of a central bank.

Dutch ships hunted whales, traded spices in India and Indonesia, and founded colonies in New Amsterdam (now New York), South Africa, and the West Indies. They also took over some Portuguese colonies. By 1640, the VOC had a trade monopoly with Japan.

The Dutch also controlled trade between European countries. The Netherlands was well-placed on major trade routes. Dutch traders shipped wine from France to the Baltic lands and brought back grain for countries around the Mediterranean Sea. By the 1680s, nearly 1000 Dutch ships entered the Baltic Sea each year.

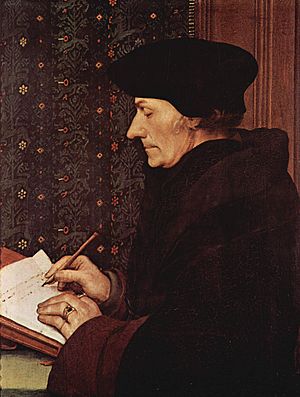

Renaissance Humanism, promoted by Desiderius Erasmus, created a tolerant atmosphere. This attracted religious refugees, like Jewish merchants from Portugal, who brought wealth. Many French Huguenots also immigrated after 1685. This intellectual tolerance attracted scientists and thinkers from all over Europe. The University of Leiden became a gathering place for them. For example, French philosopher René Descartes lived in Leiden.

Dutch lawyers were famous for their knowledge of international law. Hugo Grotius helped create international law. Book publishers thrived in the Netherlands because of the tolerant environment. Many controversial books were printed here and secretly sent to other countries.

Christiaan Huygens (1629–1695) was a famous astronomer, physicist, and mathematician. He invented the pendulum clock. Anton van Leeuwenhoek (1632-1723) greatly improved the microscope and studied microscopic life, starting the field of microbiology. Dutch engineer Jan Leeghwater (1575–1650) created new land by draining lakes with windmills.

Painting was the main art form. Dutch Golden Age painting was known for still life, landscape, and genre painting. Famous painters include Rembrandt, Johannes Vermeer, Jacob van Ruisdael, and Frans Hals.

Cities expanded greatly due to the thriving economy. New town halls and storehouses were built. Wealthy merchants built new houses along canals. Famous Dutch architects of the 17th century included Jacob van Campen and Pieter Post. Literature also flourished with writers like Joost van den Vondel. Music did not develop as much because Calvinists considered it an unnecessary luxury.

The Dutch Empire

The Dutch in the Americas

The Dutch West India Company (GWC) was given a monopoly on trade in the West Indies (Caribbean) in 1621. It also controlled the African slave trade, Brazil, and North America. Its operations stretched from West Africa to the Americas. The company was important in the Dutch colonization of the Americas. The first forts in Guyana and on the Amazon River date from the 1590s.

Actual colonization, with many Dutch settlers, was less common than with England and France. Many Dutch settlements were lost or abandoned by the end of the 17th century. However, the Netherlands kept Suriname and some Dutch Caribbean islands.

The colony of New Netherland was a private business to trade in beaver furs. It grew slowly at first due to company mismanagement and conflicts with Native Americans. In the 1650s, the colony grew dramatically and became a major trading port. It was known for its diverse population. The British took control of Fort Amsterdam in 1664. The Dutch briefly retook it in 1673 but gave it back in 1674.

Descendants of the early Dutch settlers played a big role in U.S. history, like the Roosevelt and Vanderbilt families. The Hudson Valley still has a Dutch heritage. Ideas of civil liberties and pluralism from the colony became important in American life.

Slave Trade

Even though slavery was illegal in the Netherlands itself, it was very common in the Dutch Empire and supported the economy. In 1619, the Netherlands became a leader in the large-scale Atlantic slave trade between Africa and Virginia. By 1650, it was the main slave-trading country in Europe. Historians estimate that the Dutch shipped about 550,000 African slaves across the Atlantic. About 75,000 of them died on the journey.

From 1596 to 1829, Dutch traders sold 250,000 slaves in the Dutch Guianas, 142,000 in the Dutch Caribbean islands, and 28,000 in Dutch Brazil. Tens of thousands more slaves, mostly from India, were taken to the Dutch East Indies.

The Dutch in Asia: The Dutch East India Company

The Dutch East India Company (VOC) was created in 1602. The government gave it a monopoly to trade with Asia, mainly Mughal India. It was the first multinational corporation and the first company to issue stock. It had huge powers, including making war, signing treaties, coining money, and setting up colonies.

The VOC sent almost a million Europeans to work in Asia between 1602 and 1796. It brought back over 2.5 million tons of Asian goods. The VOC made huge profits from its spice monopoly for most of the 17th century. It was very active in the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia), with its main base in Batavia (now Jakarta). It also colonized parts of Taiwan and was the only Western trading post in Japan.

By the 17th century, the VOC set up bases in parts of Ceylon (Sri Lanka) and India. However, their expansion into India stopped after they lost the Battle of Colachel to the Kingdom of Travancore. The Dutch never fully recovered from this defeat and were no longer a major colonial threat in India.

By the 18th century, the Dutch East India Company suffered from corruption and went bankrupt in 1800. Its possessions were taken over by the government and became the Dutch East Indies.

The Dutch in Africa

In 1647, a Dutch ship was wrecked in Table Bay at Cape Town. The crew built a fort and stayed for a year. The Dutch East India Company (VOC) then decided to set up a permanent settlement. They wanted a safe base where ships could stop for supplies. A small VOC expedition led by Jan van Riebeeck arrived on April 6, 1652.

To solve a labor shortage, the VOC allowed some employees to become "free burghers" (farmers). They supplied the settlement with fruit, vegetables, wheat, and wine. This group of farmers grew and expanded their farms.

Most burghers were Dutch and belonged to the Calvinist church. There were also Germans and Scandinavians. In 1688, French Huguenots, also Calvinists, joined them. The Huguenots were absorbed into the Dutch population but played a big role in South Africa's history.

From the start, the VOC used the Cape to supply ships traveling between the Netherlands and the Dutch East Indies. They imported many slaves, mainly from Madagascar and Indonesia. These slaves often married Dutch settlers. Their descendants became known as the Cape Coloureds and the Cape Malays.

During the 18th century, the Dutch settlement at the Cape grew. By the late 1700s, the Dutch Cape Colony was one of the most developed European settlements outside Europe. Its economy relied on supplying ships and agriculture.

Some free burghers moved into the rugged inland areas. Many became semi-nomadic farmers, similar to the Khoikhoi people they replaced. These were the first Trekboers (Wandering Farmers), who were very independent and isolated.

Dutch was the official language, but a new dialect formed. The Afrikaans language came mainly from 17th-century Dutch dialects. This dialect, sometimes called the "kitchen language," later became a distinct language called Afrikaans.

As the 18th century ended, Dutch trading power faded. The British took over. They seized the Cape Colony in 1795 and again in 1806. British rule was recognized in 1815. By 1806, the Dutch colony had grown to include 25,000 slaves, 20,000 white colonists, and 15,000 Khoisan people. The Dutch legacy in South Africa is clear in the Afrikaner people and the Afrikaans language.

Dutch Republic: Regents and Stadholders (1649–1784)

The Netherlands gained independence from Spain and became the Dutch Republic. As a republic, it was mostly governed by wealthy city merchants called the regents, not a king. Each city and province had its own government and laws. The Estates-General, with representatives from all provinces, made decisions for the whole Republic. However, each province also had a stadtholder, a position usually held by a member of the House of Orange-Nassau.

After gaining independence in 1648, the Netherlands tried to limit the power of France, which had replaced Spain as Europe's strongest nation. The end of the War of the Spanish Succession (1713) marked the end of the Dutch Republic as a major power. In the 18th century, it focused on staying independent and neutral.

The economy, centered on Amsterdam's role in world trade, remained strong. In 1670, the Dutch merchant fleet was huge. The province of Holland was very commercial and dominated the country. Its nobles had little influence. By 1650, wealthy merchant families controlled Holland and shaped national policies. The other six provinces were more rural and focused on flood protection.

Refugees and Economic Growth

The Netherlands welcomed many refugees, including Protestants from Antwerp, Portuguese and German Jews, French Protestants (Huguenots), and English Dissenters. Many immigrants came to Holland's cities in the 17th and 18th centuries. Amsterdam's population was almost 50% immigrants in these centuries. There was always work in Amsterdam, and tolerance was important for the economy.

The period of rapid economic growth matched the cultural bloom of the Golden Age. Amsterdam became the center of world trade. Money from refugee merchants was invested in risky ventures like expeditions to the East Indies for the spice trade. These ventures were combined into the Dutch East India Company (VOC). Profits were reinvested, leading to huge growth.

Fast industrialization led to more non-farming jobs and higher wages. Between 1570 and 1620, the labor supply grew by 3% per year. Wages increased faster than prices, so real wages for workers were much higher.

Amsterdam's Influence

By the mid-1660s, Amsterdam had reached its ideal population (about 200,000) for the available trade and commerce. The city paid the most taxes to the States of Holland, which in turn paid over half to the States General. Amsterdam was also reliable in paying taxes, giving it power.

Amsterdam was governed by a group of regents, a large but closed group of wealthy families. They controlled all parts of city life and had a strong voice in Holland's foreign affairs. Only wealthy men who had lived in the city long enough could join this ruling class. The regents provided good services, spending heavily on waterways and other infrastructure, as well as hospitals and churches.

Amsterdam's wealth came from its trade, which was supported by encouraging entrepreneurs from anywhere. This open-door policy showed a tolerant ruling class. Wealthy Sephardic Jews were welcomed, but poor Ashkenazi Jews were carefully checked. Huguenot immigrants were also given housing.

Periods Without a Stadtholder

During the wars, there was tension between the Orange-Nassau leaders (Orangists) and the merchant leaders (Republicans). The Orangists were soldiers who wanted a strong central government. The Republicans, led by the Grand Pensionary (like a prime minister), stood for local rights, trade, and peace. In 1650, the stadtholder William II, Prince of Orange died suddenly. His son was a baby, so the Orangists had no leader. The regents took the chance, and there was no new stadtholder in Holland for 22 years. Johan de Witt, a brilliant politician, became the main figure.

Princes of Orange became stadtholder and almost hereditary rulers in 1672 and 1748. The Dutch Republic was a true republic from 1650 to 1672 and from 1702 to 1748. These are called the First Stadtholderless Period and Second Stadtholderless Period.

Wars with England and France

The Dutch Republic and England were major rivals in world trade and naval power. In the mid-17th century, the Dutch navy was as powerful as Britain's Royal Navy. The Republic fought three naval wars against England from 1652 to 1674.

In 1651, England passed its first Navigation Act, which hurt Dutch trade. This led to the First Anglo-Dutch War (1652–1654). The war ended with the Treaty of Westminster (1654), which kept the Navigation Act in place.

In 1665, the Second Anglo-Dutch War began. England wanted to weaken Dutch traders. At first, England won many battles. However, the Raid on the Medway in June 1667 ended the war with a Dutch victory. The Dutch recovered their trade, and their navy became the strongest in the world. The Dutch Republic was at its peak power.

The "Disaster Year" and William III

The year 1672 is known as the "Disaster Year" (Rampjaar) in the Netherlands. England, France, Münster, and Cologne all declared war on the Republic. France, Cologne, and Münster invaded. Johan de Witt and his brother Cornelis were blamed and killed by a mob. A new stadtholder, William III, was appointed.

An Anglo-French attempt to land on the Dutch coast was stopped by Admiral Michiel de Ruyter. The French advance from the south was halted by flooding the Dutch heartland. The Dutch fought back Cologne and Münster, signing peace with them. Peace was also made with England in 1674. In 1678, peace was made with France.

In 1688, relations with England became tense again. Stadtholder William III was invited to invade England by Protestant nobles who opposed the Catholic King James II of England. This led to the Glorious Revolution. William became King of England, ruling with his wife Mary. This made England a key ally for the United Provinces against France. William led the Dutch and English armies until his death in 1702.

Economic Decline and Culture

During the Second Stadtholderless Period (1702–1747), the Republic lost its status as a major power and its leading role in world trade. The economy declined, causing industries and cities to shrink in some areas. However, wealthy people continued to accumulate capital, making the Republic a leader in international finance. A military crisis led to the return of the Stadtholderate in 1747.

The slow economic decline after 1730 was relative. Other countries grew faster, catching up to and surpassing the Dutch. Holland lost its world dominance in trade as competitors emerged. There was little growth in manufacturing, possibly due to high wages. Wealthy people invested their money in foreign loans.

Dutch culture also declined in arts and sciences. Literature copied English and French styles. The most influential thinker was Pierre Bayle, a Protestant refugee who wrote a huge dictionary that influenced the The Enlightenment across Europe.

Religious life became more relaxed. Catholics gained more tolerance. Dutch universities became less important. Dutch painting also declined, with painters copying old masters.

Life for the average Dutchman became slower in the 18th century. The upper and middle classes remained wealthy. Unskilled laborers remained poor. A large group of unemployed people needed charity to survive.

The Orangist Revolution and Later Rule

During the War of Austrian Succession, French attacks on Dutch forts led to calls for the return of the stadtholderate. William IV, Prince of Orange, took this chance to gain power. The war ended in 1748. William IV died unexpectedly in 1751 at age 40.

His son, William V, was only 3 years old. A long period of rule by others, marked by corruption, followed. William V became stadtholder in 1766. In 1767, he married Princess Wilhelmina of Prussia.

The Netherlands remained neutral during the American War of Independence (1775-1783). William V, who was pro-British, blocked efforts to join the war. However, the Dutch tried to join a league of neutral countries, leading to the disastrous Fourth Anglo-Dutch War in 1780. The war ended badly for the Dutch, showing the country's weaknesses.

The French-Batavian Period (1785–1815)

After the war with Great Britain ended in 1784, there was growing unrest and a rebellion by the anti-Orangist Patriots. The French Revolution led to the creation of a pro-French Batavian Republic (1795–1806). Then, the Kingdom of Holland was created, ruled by Napoleon's brother (1806–1810). Finally, the Netherlands was directly taken over by the French Empire (1810–1813).

Patriot Rebellion and French Influence

Influenced by the American Revolution, the Patriots wanted a more democratic government. Their goal was to reduce corruption and the power of the stadtholder, William V, Prince of Orange. Support for the Patriots came mostly from the middle class. They formed militias called exercitiegenootschappen.

In 1785, there was an open Patriot rebellion. It was an armed uprising in some Dutch towns. The Patriots wanted to remove government officials and force new elections. This revolution was a series of violent and confused events. The Patriot movement focused on local political power. They were able to limit the stadholder's power and hold democratic elections in some towns.

In 1785, the stadholder William V moved his court to Nijmegen. In June 1787, his wife Wilhelmina tried to travel to The Hague but was stopped by Patriot militiamen. She asked her brother, the King of Prussia, for help. He sent 26,000 troops to stop the rebellion. The Patriot militias could not fight these forces. Many Patriots, about 40,000, fled to France and other places.

Soon, the French became involved in Dutch politics. In January 1795, the French army invaded. The Patriots rose up, overthrew the governments, and declared the Batavian Republic in Amsterdam. Stadtholder William V fled to England. The new government was controlled by France. The Batavian Republic was popular and sent soldiers to fight with the French.

The old Dutch Republic's federal structure was replaced by a single, unified state. Ministerial government was introduced for the first time. Meanwhile, the exiled stadtholder gave the Dutch colonies to Great Britain for "safekeeping." This ended the colonial empire in Guyana, Ceylon, and the Cape Colony. The Dutch East Indies were returned to the Netherlands later.

Kingdom of Holland and French Annexation

In 1806, Napoleon turned the Netherlands into the Kingdom of Holland, putting his brother Louis Bonaparte on the throne. Louis was unpopular but sometimes defied his brother for his new kingdom. Napoleon forced him to step down in 1810 and directly annexed the Netherlands into the French empire. This meant economic controls and forced military service for young men.

When the French retreated in 1813, a temporary government took over. They called William V's son, William Frederick, back. He refused the crown but declared himself "hereditary sovereign prince" on December 6.

The major European powers secretly agreed to combine the northern Netherlands with the more populated Austrian Netherlands and Prince-Bishopric of Liège into one monarchy. This stronger country on France's northern border was meant to keep France's power in check. In 1814, William Frederick gained control over the Austrian Netherlands and Liège.

On March 15, 1815, William Frederick became King William I. This was made official later in 1815, when the Low Countries were formally recognized as the United Kingdom of the Netherlands. The crown became a hereditary position for the House of Orange-Nassau.

United Kingdom of the Netherlands (1815–1839)

William I became king and also the hereditary Grand Duke of Luxembourg. The new country had two capitals: Amsterdam and Brussels. The north (Netherlands proper) had 2 million people, mostly Protestant with a large Catholic minority. The south (Belgium) had 3.4 million people, almost all Catholic, divided between French-speaking Walloons and Dutch-speaking Flemings.

The new nation was doing well. Death rates were low, food supply was good, and education was improving. The best years were in the mid-1820s. In 1806, the Dutch had started to modernize education, focusing on teacher training. By 1826, the Dutch government spent much more on education than France.

Constitutional Monarchy and Belgian Independence

William I, who ruled from 1815 to 1840, had great power. He accepted the modern changes of the past 25 years, like equality before the law. However, he brought back the old social classes and made many people nobles. Voting rights were still limited. The government was now unified, with all power coming from the center.

William I was a Calvinist and did not fully understand the Catholic majority in the south. He changed the "Fundamental Law of Holland," which removed the Catholic Church's privileges and gave equal rights to all religions. This did not please the Catholic bishops.

William I actively promoted economic modernization. The first 15 years of the Kingdom saw progress and wealth. Industry grew quickly in the south, with new textile factories powered by local coal mines. There was little industry in the north, but most overseas colonies were returned, and profitable trade resumed. The country prospered until problems arose with the southern provinces.

Belgium Breaks Away

William wanted to create a united people, but the north and south had grown very different. Protestants were the largest group in the North, but a minority in the Catholic South. Protestants dominated William's government and army. Catholics in the South did not feel part of the United Netherlands. Economic differences (industrial South, merchant North) and language (French in Wallonia, Dutch in Flanders) also contributed.

The French-speaking elite in the South felt like second-class citizens. William's policies were unpopular in the Catholic South. Walloons strongly rejected his attempt to make Dutch the official language. Flemings were divided; some welcomed Dutch, others preferred French. Catholics resented being under a Protestant government. Political liberals in the south complained about the king's strict rule. All southerners felt they were not fairly represented in the government.

The revolution in France in 1830 sparked action in Belgium. At first, they wanted more self-rule, then full independence. William hesitated, and his attempts to retake Belgium failed due to Belgian resistance and opposition from major European powers.

At the London Conference of 1830, European powers ordered a ceasefire between the Dutch and Belgians. William I rejected the first peace treaty and resumed fighting. French and British intervention forced William to withdraw Dutch forces from Belgium in late 1831. In 1833, a long ceasefire was agreed upon. Belgium was effectively independent. The final separation treaty of 1839 divided Luxembourg and Limburg between the Dutch and Belgian crowns. The Kingdom of the Netherlands then consisted of the 11 northern provinces.

Democratic and Industrial Development (1840–1900)

The Netherlands did not industrialize as fast as Belgium after 1830, but it was still prosperous. Government policies helped create a national economy. These included removing internal tariffs, having one currency, modern tax collection, and building roads, canals, and railroads. However, compared to Belgium, the Netherlands was slow to industrialize. This might be due to higher costs and a focus on trade rather than industry.

In the Dutch coastal areas, farming was very productive. So, industrial growth came later, after 1860, because there was less need for people to move to factories. However, the provinces of North Brabant and Overijssel did industrialize and became economically advanced.

Like the rest of Europe, the 19th century saw the Netherlands become a modern, middle-class industrial society. Fewer people worked in farming. The country worked hard to regain its position in shipping and trade. The Netherlands caught up with Belgium in industrialization around 1920. Major industries included textiles and later, the Philips company. Rotterdam became a big shipping and manufacturing center. Poverty slowly decreased as working conditions improved.

Constitutional Reform and Liberalism

In 1840, William I stepped down, and his son, William II, became king. William II tried to continue his father's policies but faced a strong liberal movement. In 1848, there was unrest across Europe. These events convinced King William II to agree to liberal and democratic reforms. That same year, Johan Rudolf Thorbecke, a leading liberal, was asked to write a new constitution.

The new constitution, proclaimed on November 3, 1848, greatly limited the king's powers. It made the government accountable only to an elected parliament and protected civil liberties. This new liberal constitution was accepted in 1848. The relationship between the monarch, government, and parliament has stayed mostly the same since then.

William II was followed by William III in 1849. The new king reluctantly chose Thorbecke to lead the government. Thorbecke introduced liberal measures, like expanding voting rights. However, his government soon fell when Protestants protested against the Catholic Church re-establishing its bishops. A conservative government was formed, but it did not undo the liberal changes. Catholics finally gained equality after two centuries.

Dutch political history from the mid-19th century until the First World War was about expanding liberal reforms, modernizing the economy, and the rise of trade unions and socialism. Prosperity grew hugely.

Religion and "Pillarization"

Religion was a big issue, with repeated arguments over the role of church and state in education. In 1816, the government took control of the Dutch Reformed Church. In 1857, all religious teaching ended in public schools. However, different churches set up their own schools and even universities.

By the mid-19th century, most Dutch people belonged to the Dutch Reformed Church or other Protestant groups (around 55%), or the Roman Catholic Church (35% to 40%). A powerful group of Protestants were actually secular liberals who wanted to reduce religious influence. In response, Catholics and devout Calvinists joined together against these secular liberals.

The Netherlands remained one of the most tolerant countries in Europe regarding religion. However, conservative Protestants faced opposition when they tried to create separate communities. By the end of the century, religious persecution had completely stopped.

Dutch social and political life became divided into separate parts based on religion. This was called "pillarization" (Verzuiling). The economy was not affected. Abraham Kuyper (1837–1920), a leading politician and theologian, was important in creating pillarization. He set up Calvinist organizations and argued for a society of organized minorities.

After 1850, pillarization became a way to avoid internal conflict. Everyone belonged to one "pillar" (zuil) based mainly on religion (Protestant, Catholic, or secular). The secular pillar later split into a socialist/working-class pillar and a liberal (pro-business) pillar. Each pillar had its own organizations, including churches, political parties, schools, unions, and newspapers. People from different pillars lived near each other and did business, but rarely mixed socially or married.

Pillarization was officially recognized in the Pacification of 1917. This agreement gave socialists and liberals universal male voting rights, and religious parties were guaranteed equal funding for all schools. In politics, leaders of the pillars cooperated, and public life generally ran smoothly.

Flourishing of Art, Culture, and Science

The late 19th century saw a cultural revival. The Hague School brought a return of realist painting from 1860 to 1890. The world-famous Dutch painter was Vincent van Gogh, though he spent most of his career in France. Literature, music, architecture, and science also thrived.

A notable scientist was Johannes Diderik van der Waals (1837–1923), who taught himself physics and won the Nobel Prize in 1910 for his work in thermodynamics. Hendrik Lorentz (1853–1928) and his student Pieter Zeeman (1865–1943) shared the 1902 Nobel Prize in physics. Other important scientists included biologist Hugo de Vries, who rediscovered Mendelian genetics.

1900 to 1940

In 1890, William III died and was succeeded by his young daughter, Queen Wilhelmina (1880–1962). She ruled the Netherlands for 58 years. When she became queen, the personal union between the Netherlands and Luxembourg ended because Luxembourg law did not allow women to rule.

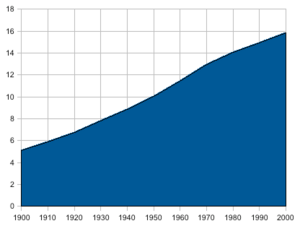

This period saw more growth and colonial development. However, it was also marked by the difficulties of World War I (where the Netherlands was neutral) and the Great Depression. The Dutch population grew quickly in the 20th century as death rates fell and industrialization created jobs. Between 1900 and 1950, the population doubled from 5.1 to 10 million people.

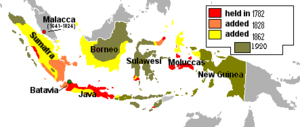

Colonial Focus

The Dutch empire included the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia), Suriname in South America, and some smaller areas. The empire was run from Batavia (in Java), where the governor had almost complete power. The Dutch slowly expanded their control to include all of modern Indonesia by 1920.

The colony brought economic opportunities to the Netherlands. One exception was in 1860, when Eduard Dekker, writing as "Multatuli", wrote the novel Max Havelaar: Or The Coffee Auctions of the Dutch Trading Company. He criticized the exploitation of the colony. The book helped inspire the Indonesian independence movement and the "Fair trade" movement for coffee.

The military forces in the Dutch East Indies were controlled by the governor, not the regular Dutch army. The Aceh war (1873–1913) was a long, costly fight against the Achin (Aceh) state in northern Sumatra.

Neutrality During World War I

The Netherlands had not fought a major war since the 1760s, so its military had become weaker. The Dutch decided not to ally with anyone and remained neutral in all European wars, especially the First World War.

Germany's war plan (the Schlieffen Plan) was changed in 1908 to invade Belgium but not the Netherlands. The Netherlands supplied Germany with important raw materials like rubber, tin, and food. The British used their blockade to limit what the Dutch could send to Germany.

Both the Allies and the Central Powers found it useful for the Netherlands to stay neutral. The Netherlands controlled the mouths of the Scheldt, Rhine, and Meuse rivers. If one country invaded, another would counterattack to protect its interests in the rivers. It was too risky for any nation to fight on another front.

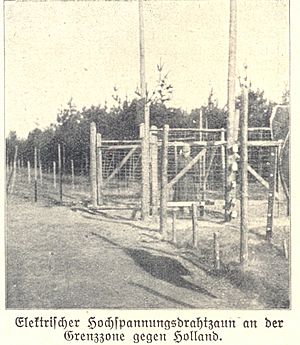

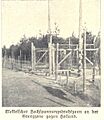

The Dutch were affected by the war. Troops were mobilized, and forced military service was introduced. Food shortages were widespread because the warring countries controlled Dutch supplies. Food riots even broke out. Smuggling was a big problem. When Germany conquered Belgium, the Allies stopped exporting to Belgium, causing food shortages there. This led to Dutch smuggling, which caused inflation and more food shortages in the Netherlands. The government took steps to stop smuggling and remain neutral. Germany built an electrified fence along the Belgian–Dutch border, which caused many Belgian refugees to die.

Between the World Wars

Until 1917, only men with high incomes could vote. Pressure from socialist movements led to elections where all men could vote. In 1919, women also gained the right to vote.

The worldwide Great Depression, which began in 1929, had severe effects on the Dutch economy. It lasted longer than in most other European countries. This was often due to the Dutch government's strict financial policy and its decision to stick to the gold standard longer than its trading partners. The Great Depression led to high unemployment, widespread poverty, and social unrest.

The rise of Nazism in Germany caused concern in the Netherlands. Most Dutch people expected Germany to respect their neutrality again. There were small fascist and Nazi movements in the 1930s, but most Dutch people rejected their ideas.

The defense budget was not increased until Germany re-militarized the Rhineland in 1936. It was increased again in 1938 after Austria was taken over. The colonial government also increased its military budget due to tensions with Japan. The Dutch did not mobilize their armed forces until shortly before France and the UK declared war on Germany in September 1939. Neutrality was still the official policy, but the Dutch government tried to buy new weapons.

The Second World War (1939–1945)

Nazi Invasion and Occupation

When World War II began in 1939, the Netherlands again declared neutrality. However, on May 10, 1940, Nazi Germany invaded the Netherlands and Belgium. Fighting against the Dutch army was harder than expected for the Germans. The northern attack was stopped, and the central one slowed down. Many German airborne troops were killed.

Only in the south were defenses broken, but the Dutch held the passage over the River Maas at Rotterdam. By May 14, fighting had stopped in many places, and the German army made little progress. So, the Luftwaffe bombed Rotterdam, killing about 900 people and destroying most of the city center.

After the bombing and German threats to bomb Utrecht, the Netherlands surrendered on May 15. The Dutch Royal Family and some armed forces fled to the United Kingdom. Some members of the Royal Family later moved to Ottawa, Canada.

Resentment against the Germans grew as the occupation became harsher. Many Dutch people joined the resistance. However, some also collaborated. Thousands of young Dutch men volunteered to fight for the Germans.

The Holocaust in the Netherlands

About 140,000 Jewish people lived in the Netherlands at the start of the war. Persecution of Dutch Jews began soon after the occupation. By the end of the war, only 40,000 Jews were still alive. Of the 100,000 Jews who did not go into hiding, about 1,000 survived.

The most famous victim was Anne Frank. Her diary, written while hiding from the Nazis, was found and published after the war. Her father, Otto Frank, was the only family member to survive.

The War in the Dutch East Indies

On December 8, 1941, the Netherlands declared war on Japan. Japanese forces invaded the Dutch East Indies on January 11, 1942. The Dutch surrendered on March 8. Dutch citizens and people of Dutch ancestry were captured and put into labor camps. Many Dutch ships, planes, and military personnel escaped to Australia and continued fighting.

The Hunger Winter and Liberation

In Europe, after the Allies landed in Normandy in June 1944, progress was slow. The First Canadian Army and the Second British Army began operations in the Netherlands in September. On September 17, Operation Market Garden tried to capture bridges across three major rivers in the south. Despite fierce fighting, the bridge at Arnhem could not be captured.

Areas south of the Rhine river were freed between September and December 1944. This included Zeeland, which was liberated in October and November in the Battle of the Scheldt. This opened the port of Antwerp for Allied shipping. The rest of the country remained occupied until spring 1945. The Nazis deliberately cut off food supplies, causing near-starvation in cities during the Hongerwinter (Hunger Winter) of 1944–1945. Many vulnerable people died.

The First Canadian Army launched Operation Veritable in February, breaking through German defenses and reaching the Rhine. In the final weeks of the war, the First Canadian Army cleared the Netherlands of German forces.

The Liberation of Arnhem began on April 12, 1945. Within four days, Arnhem was under Allied control. The Canadians advanced further. On April 27, a truce allowed food aid to reach starving Dutch civilians. On May 5, 1945, German forces in the Netherlands surrendered. (May 5 is now celebrated as Liberation Day.) Three days later, Germany surrendered, ending the war in Europe.

After the war, the Dutch were traumatized. Their economy was ruined, infrastructure shattered, and several cities destroyed.

Post-War Events

There were punishments for those who had worked with the Nazis. Artur Seyss-Inquart, the Nazi Commissioner of the Netherlands, was tried at Nuremberg.

In the early post-war years, the Netherlands tried to expand its territory by taking German land. Larger plans were rejected by the United States, but a smaller annexation was allowed in 1949. Most of this land was returned to Germany in 1963.

Operation Black Tulip was a plan in 1945 to remove all Germans from the Netherlands. From 1946 to 1948, 3,691 Germans were deported. They were taken from their homes and sent to camps near the German border.

Prosperity and European Unity (1945–Present)

The post-war years brought hardship, shortages, and natural disasters. This was followed by large public works, economic recovery, European integration, and the creation of a welfare state.

Immediately after the war, many goods were rationed. There was a severe housing shortage. In the 1950s, many Dutch people emigrated, especially to Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. About 500,000 Dutch people left the country. The Netherlands lost control of the Dutch East Indies, as Indonesia became independent. About 300,000 Dutch inhabitants and their Indonesian allies left the islands.

Post-war politics saw changing coalition governments. The Catholic People's Party (KVP) and the socialist Labour party (PvdA) were the largest parties. The United States provided economic aid through the Marshall Plan in 1948. This helped the economy, encouraged business modernization, and promoted economic cooperation.

The 1948 elections led to a new government led by Labor's Willem Drees. His time in office saw four major developments: decolonization, economic rebuilding, the creation of the Dutch welfare state, and international cooperation. This included forming Benelux, NATO, and the ECSC.

Baby Boom and Economic Rebuilding

Despite problems, this was a time of hope. A baby boom followed the war. Young Dutch couples, who had lived through the Great Depression and the war, wanted to start fresh. They wanted better lives without poverty and strict rules. The book The Common Sense Book of Baby and Child Care by American pediatrician Benjamin Spock was a bestseller. It promoted a more relaxed and enjoyable family life.

Wages were kept low, and consumption was delayed to allow for quick rebuilding of infrastructure. After the war, unemployment fell, and the economy grew very fast. The destroyed cities were rebuilt. The Marshall Plan was key to this recovery, providing funds and goods.

Dutch companies like Royal Dutch Shell and Philips became important internationally. Dutch businesspeople, scientists, and engineers made big contributions. For example, Dutch economists like Jan Tinbergen helped develop econometrics.

From 1973 to 1981, the booming economy of the 1960s ended. The Netherlands also experienced years of negative growth. Unemployment increased, leading to more social-security spending. Inflation reached double digits. However, rich natural gas resources provided a trade surplus.

Flood Control

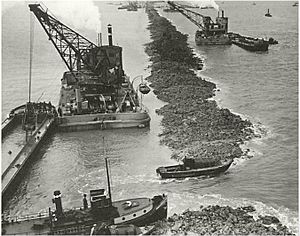

The last major flood in the Netherlands happened in early February 1953. A huge storm caused several dikes to collapse, and over 1,800 people drowned.

The Dutch government then started a large public works program called the "Delta Works" to protect the country from future floods. The project took over 30 years to complete. The Oosterscheldedam, an advanced sea storm barrier, opened in 1986. The Delta program continues to manage these works to make the Netherlands safe from climate change and water by 2050.

Europeanization and International Role

The European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) was founded in 1951 by Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, West Germany, France, and Italy. Its goal was to combine steel and coal resources and support economies. It also helped reduce tensions between countries that had recently fought each other. This economic group grew to become the European Union (EU).

The United States gained more influence after the war. American culture, films, and consumer goods became popular. The Marshall Plan also introduced American business practices. NATO brought American military ideas.

The Netherlands is a founding member of the EU, NATO, OECD, and WTO. With Belgium and Luxembourg, it forms the Benelux economic union. The country hosts the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons and five international courts in The Hague, making it "the world's legal capital."

Decolonization and Multiculturalism

The Dutch East Indies had been a valuable resource for the Netherlands. By the 20th century, an educated Indonesian elite had developed. Increased political activity and Japanese occupation weakened Dutch rule. Indonesian nationalists declared independence on August 17, 1945. The Dutch were too weak to reconquer the country.

Hundreds of thousands of Indonesians who supported the Dutch moved to the Netherlands when independence came. The UK helped reach a compromise in 1947. Increasing international pressure, including from the U.S., forced the Netherlands to withdraw. The Netherlands formally recognized Indonesian independence on December 27, 1949. Only Dutch New Guinea remained under Dutch control until 1961.

During and after the Indonesian National Revolution, over 350,000 people left Indonesia for the Netherlands. This included Europeans and "Indos" (Dutch-Indonesian Eurasians). After Suriname's independence in 1975, 115,000 Surinamese also moved to the Netherlands. The Indos are now the largest ethnic minority group in the Netherlands. They are integrated but have kept aspects of their culture.

The Dutch economy grew very well in the 1950s and 1960s. There was such a high demand for labor that immigration was encouraged, first from Italy and Spain, then from Turkey and Morocco.

Suriname became independent on November 25, 1975. The Dutch government supported this to stop immigration from Suriname and end its colonial status. However, about one-third of Suriname's population moved to the Netherlands, fearing political unrest.

Liberalization and Recent Politics

When the post-war baby boom children grew up, they led a revolt against strict rules in Dutch life in the 1960s and 1970s. This led to rapid de-pillarization, where old divisions based on class and religion broke down. A youth culture emerged, with student rebellion, informal clothes, and protests for women's rights and environmental issues.

Secularization, or the decline in religious practice, started after 1960. As the social distance between Calvinists and Catholics decreased, their political parties merged. The Anti-Revolutionary Party (ARP) merged with the Catholic People's Party (KVP) and the Christian Historical Union (CHU) in 1977 to form the Christian Democratic Appeal (CDA).

After 1982, the welfare system was reduced, especially pensions and unemployment benefits.

After the 1994 general election, a "purple" coalition was formed without the CDA. This government introduced new laws based on official tolerance. In 2001, the Netherlands became the first country to legalize same-sex marriage. The Purple Coalition also oversaw a period of great economic prosperity.

At the 1998 election, the Purple Coalition grew stronger. Voters rewarded them for their economic performance, which included lower unemployment and steady growth.

Two events changed the political landscape:

- On May 6, 2002, politician Pim Fortuyn, who wanted strict immigration policies, was assassinated. This shocked the nation. His party won a huge election victory, partly due to his death. However, internal problems led to the party losing most of its support in 2003.

- Another murder happened on November 2, 2004, when filmmaker Theo van Gogh was killed by a Dutch-Moroccan youth with extremist views. This sparked a debate on Islamic extremism, Islam in Dutch society, and immigration.

21st Century Developments

By 2000, the population reached 15.9 million, making the Netherlands one of the most densely populated countries. Urban development led to the Randstad, a large urban area including Amsterdam, Rotterdam, The Hague, and Utrecht, with a population of 7.1 million.

On December 26, 2004, many Dutch people were among the thousands killed by the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami off Indonesia.

This small nation has become one of the most open, dynamic, and prosperous countries in the world. It had the tenth-highest income per person in 2011. It has a strong, market-based economy. In May 2011, the OECD ranked the Netherlands as the "happiest" country in the world.

On Koningsdag (King's Day), April 30, 2013, Prince Willem Alexander became King after his mother, Queen Beatrix, stepped down.

On July 17, 2014, 193 Dutch people were among the 298 killed when Malaysia Airlines Flight MH17 was shot down in Eastern Ukraine.

In March 2021, Prime Minister Mark Rutte's center-right VVD party won the elections. Rutte, in power since 2010, formed his fourth coalition government.

Images for kids

-

Tribes during the Roman Empire

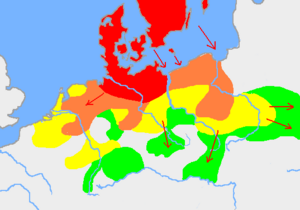

-

Expansion of the Franks from 481 to 870

-

Saint Willibrord, Anglo-Saxon missionary from Northumberland, Apostle to the Frisians, first bishop of Utrecht

-

Chapel of St Nicholas (Sint-Nicolaaskapel (Nijmegen) or Valkhofkapel) in Nijmegen, one of the oldest buildings in the Netherlands

-

Dirk VI, Count of Holland, 1114–1157, and his mother Petronella visiting the work on the Egmond Abbey, Charles Rochussen, 1881. The sculpture is the Egmond Tympanum, depicting the two visitors on either side of Saint Peter.

-

Jacqueline, Countess of Hainaut, 1401–1436, known to the Dutch as "Jacoba of Bavaria"

-

Desiderius Erasmus, 1466–1536, Rotterdam Renaissance humanist, Catholic priest and theologian, by Hans Holbein the Younger, 1523

-

Title page of the 1637 Statenvertaling, the first Bible translated from the original Hebrew and Greek into Dutch, commissioned by the Calvinist Synod of Dort, used well into the 20th century

-

1595 painting by Isaac van Swanenburg illustrating Leiden textile workers.

-

William I, Prince of Orange, called William the Silent.

-

Prince Maurits at the Battle of Nieuwpoort, 1600 CE, by Paulus van Hillegaert

-

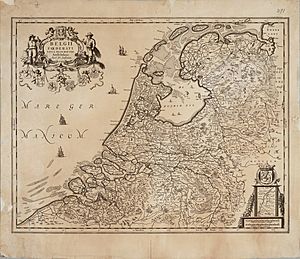

Leo Belgicus, a map of the low countries drawn in the shape of a lion, by Claes Jansz. Visscher (II), 1611 CE

-

The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp, by Rembrandt van Rijn, 1632 CE

-

Antonie van Leeuwenhoek was a businessman and scientist in the Golden Age of Dutch science and technology.

-

Johannes Vermeer's Girl with a Pearl Earring

-

The Dutch Classicist Mauritshuis, named after Prince Johan Maurits and built 1636–1641, was designed by Jacob van Campen and Pieter Post.

-

Peter Stuyvesant, Director-General of New Netherland (New York). His provincial capital, New Amsterdam, was located at the southern tip of the island of Manhattan.

-

Dutch East India Company factory in Hugli-Chuchura, Mughal Bengal. Hendrik van Schuylenburgh, 1665

-

Dutch Batavia built in what is now Jakarta, by Andries Beeckman c. 1656 CE

-

Eustachius De Lannoy of the Dutch East India Company surrenders to Maharaja Marthanda Varma of the Indian Kingdom of Travancore after the Battle of Colachel. (Depiction at Padmanabhapuram Palace)

-

Painting of an account of the arrival of Jan van Riebeeck, by Charles Bell

-

Johan de Witt (born 1625, died 1672), Grand Pensionary of Holland, painted between 1643 and 1700 after Jan de Baen

-

Willem III, Prince of Orange, born 1650, died 1702, reigned as William III of England from 1689 to 1702 after the Glorious Revolution.

-

The Inspectors of the Collegium Medicum in Amsterdam, by Cornelis Troost, 1724. This period is known as the "Periwig Era".

-

William IV, Prince of Orange, stadholder from 1747 to 1751 CE

-

Willem V of Orange, stadholder from 1751 to 1806, and Wilhelmina of Prussia with three of their five children. From left to right: the future William I of the Netherlands, Frederick, and Frederica Louise Wilhelmina.

-

Firefight on the Vaartse Rijn at Jutphaas on 9 May 1787. The pro-revolutionary Utrecht Patriots are on the right; the troops of stadholder William V, Prince of Orange on the left. (Painted by Jonas Zeuner, 1787)

-

Administrative divisions of the First French Empire in 1812, illustrating the incorporation of the Netherlands and its internal reorganisation

-

Landing of the future king William I at Scheveningen on 30 November 1813

-

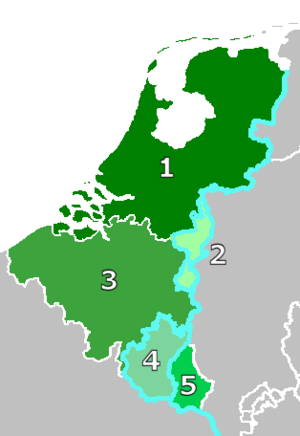

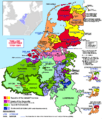

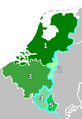

The Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg and Limburg in 1839

1, 2 and 3 United Kingdom of the Netherlands (until 1830)

1 and 2 Kingdom of the Netherlands (after 1839)

2 Duchy of Limburg (1839–1867) (in the German Confederacy after 1839 as compensation for Waals-Luxemburg)

3 and 4 Kingdom of Belgium (after 1839)

4 and 5 Grand Duchy of Luxembourg (borders until 1839)

4 Province of Luxembourg (Waals-Luxemburg, to Belgium in 1839)

5 Grand Duchy of Luxembourg (German Luxemburg; borders after 1839)

In blue, the borders of the German Confederation. -

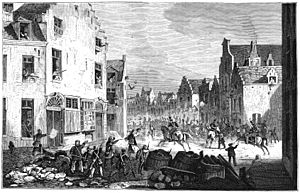

Fighting between Belgian rebels and the Dutch military expedition in Brussels in September 1830

-

Shepherdess With a Flock of Sheep by Anton Mauve (1838–1888), of the Hague School

-

Peasant woman, seated, with a white hood, painted in Nuenen in December 1884 by Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890). Born in Groot-Zundert, van Gogh was a Dutch post-Impressionist painter whose work, notable for its rough beauty, emotional honesty and bold color, had a far-reaching influence on 20th-century art.

-

Queen Wilhelmina, queen of the Netherlands from 1890 to 1948

-

Map of the Dutch East Indies showing its expansion from 1800 to 1942

-

The Afsluitdijk, the dike closing off the Zuiderzee, was constructed between 1927 and 1933. Public works projects like this were one way to deal with high unemployment during the Great Depression.

-

Yellow Star of David with Jood, the Dutch word for "Jew".

-

Identification papers issued to Dutch people during the war.

-

Dutch civilians celebrating the arrival of I Canadian Corps troops in Utrecht after the German surrender, 7 May 1945

-

A town in Zuid Beveland inundated in 1953

-

Protest in The Hague against the nuclear arms race between the U.S./NATO and the Warsaw Pact, 1983

-

Wim Kok served as Prime Minister of the Netherlands from 22 August 1994 until 22 July 2002.

-

Dutch Prime Minister Jan Peter Balkenende and U.S. President George W. Bush in the Oval Office on 5 June 2008

-

Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte and U.S. President Donald Trump in the Oval Office on 18 July 2019

See also

In Spanish: Historia de los Países Bajos para niños

In Spanish: Historia de los Países Bajos para niños

- Canon of the Netherlands

- Culture of the Netherlands

- Demographics of the Netherlands

- Dutch diaspora

- Dutch East Indies

- Dutch Empire

- Economy of the Netherlands

- Geography of the European Netherlands

- History of Belgium

- History of religion in the Netherlands

- History of Europe

- History of Germany

- History of Luxembourg

- List of prime ministers of the Netherlands

- List of monarchs of the Netherlands

- Politics of the Netherlands

- Provinces of the Netherlands

- Netherlands in World War II

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |