Low Countries theatre of the War of the First Coalition facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Low Countries theatre ofthe War of the First Coalition Flanders campaign |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of the First Coalition | |||||||

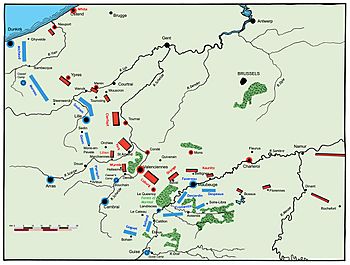

The French conquest of the Low Countries from May 1794 until June 1795 |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

|

||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

||||||

The Flanders Campaign was a series of battles fought between 1792 and 1795. It took place in the Low Countries (modern-day Belgium and the Netherlands) during the early years of the War of the First Coalition. This war was a big conflict between revolutionary France and several European countries.

At this time, the French Revolution was changing France a lot. The French government got rid of the king and wanted to spread its new ideas to other countries, even by fighting. Many European countries, like Austria, Great Britain, and the Dutch Republic, formed an alliance called the First Coalition. They wanted to stop the French Revolution from spreading and bring back the old ways.

The fighting started in April 1792. The French tried to invade the Austrian Netherlands (now Belgium) but failed at first. Later, they won a big battle at Jemappes in November 1792. This allowed them to take control of much of Belgium. However, the Coalition fought back and won a major victory at Neerwinden in March 1793, pushing the French out.

The main fighting then moved to the border between France and Flanders. Here, armies from Britain, Austria, the Dutch Republic, and other German states faced off against the French. The Allies won some early battles but couldn't break through French defenses. Eventually, the French launched strong counter-attacks. Austria also decided to move some of its troops to Poland, which weakened the Allied forces.

The Allies had to retreat through a very cold winter in 1794-1795. The Austrians went back to the Rhine River, and the British were sent home. The French, helped by Dutch and Belgian "Patriots" who wanted to change their own countries, pushed forward. They took over the Dutch Republic and created a new country called the Batavian Republic, which was controlled by France. They also took over the Austrian Netherlands and the area around Liège, adding them to France.

This French victory changed the map of Europe. Prussia and Hesse-Kassel made peace with France in 1795, giving up some land. Austria finally accepted losing Belgium in 1797. The Dutch leader, William V, Prince of Orange, fled to England. He didn't recognize the new Batavian Republic at first.

Contents

Why the War Started

France, Britain, and the Dutch Republic

In the 1780s, France helped the American colonies become independent from Britain. This was a success for France, but it left the country with huge debts. Britain and France tried to improve their trade, but it didn't really help France's money problems.

The Dutch Republic was also having problems. Its leader, William V, Prince of Orange, wanted to support Britain. But many Dutch citizens, called "Patriots," supported the American rebels and wanted more freedom for themselves. This led to a war between Britain and the Dutch Republic, which badly damaged the Dutch navy.

The Dutch army was also weak. A pamphlet called Aan het Volk van Nederland (To the People of the Netherlands) encouraged citizens to arm themselves and overthrow the leader. This led to a small civil war in 1786-1787. William V only won with help from Prussian and British soldiers. Many Patriots had to flee to France.

After this, the Dutch Republic became very close to Britain and Prussia. When the French Revolution began in 1789, Britain and the Dutch Republic stayed neutral at first. They didn't want to get involved in France's internal problems.

Southern Netherlands, Austria, and Prussia

At the same time, there were also big changes happening in the Austrian Netherlands (modern Belgium). The ruler, Emperor Joseph II, tried to make many changes that upset the local nobles and church leaders.

Some Belgian revolutionaries tried to get help from the Dutch and British to fight the Austrians. Only Prussia showed some interest, hoping to weaken Austria. In 1789, Joseph II took away many old rights and privileges. This led to a rebellion called the Brabant Revolution. The rebels defeated the Austrian army and created the United Belgian States. Another revolution happened nearby in Liège, creating the Liège Republic. Prussia unofficially protected these new states.

However, no major country truly supported the new Belgian state. The Belgian rebels themselves were divided. After Joseph II died, his brother Leopold II became emperor. He made a deal with Prussia, and Austrian troops returned to Belgium, ending the United Belgian States and the Liège Republic in 1791. But many revolutionaries still wanted change. When French armies invaded in 1792, these Belgian and Liège revolutionaries helped them.

War Begins

The French king, Louis XVI of France, tried to escape France in June 1791 but was caught. This made many French people even more against the king and in favor of a republic. Austria and Prussia then warned France that they would intervene if the French royal family was harmed.

The Girondins, a powerful group in the French government, wanted to spread the revolution to other countries. King Louis XVI also hoped that if France lost a war, he would get his full power back. So, on April 20, 1792, King Louis XVI declared war on Austria. Prussia immediately joined Austria. Britain and the Netherlands tried to stay neutral, but Britain was worried about the safety of the Dutch Republic.

The main Allied commander was the Austrian Prince of Saxe-Coburg. When Britain joined the war, the Duke of York (the British king's son) also had to follow orders from London. This meant that military decisions were often influenced by political goals from Vienna and London.

The French army was in a difficult state. Old soldiers fought alongside new volunteers. Many experienced officers had left France, especially in the cavalry. Only the artillery was still strong. Things got even harder when France started forcing all young men to join the army in 1793. French commanders had to balance protecting the border with winning battles to keep the government in Paris happy. If they failed, they could face severe punishment.

1792 Campaign

Early French Struggles

The first battles in the north, near Quiévrain and Marquain in April 1792, were a disaster for the French. Their unprepared armies were easily pushed out of the Austrian Netherlands. The French were on the defensive for months. But then, they won an unexpected victory at Valmy in September 1792. This changed everything and opened the way for a new invasion north. The very next day, the French officially got rid of the monarchy and created the French First Republic.

Battle of Jemappes and Austrian Retreat

On November 6, 1792, the French commander Charles François Dumouriez won a surprise victory at the Battle of Jemappes. By the end of 1792, Dumouriez had marched through most of the Austrian Netherlands and the area around Liège (modern Belgium) without much resistance. The Austrians retreated. Dumouriez saw a chance to overthrow the weak Dutch Republic by moving north.

The French government declared that they would reopen the Scheldt River for ships, which had been closed for 200 years. They also said French armies could chase Austrian troops into neutral areas. Britain saw this as a violation of the Netherlands' neutrality and started getting ready for war. The Dutch leader, William V, joined the anti-French alliance. This gave France a reason to invade the Dutch territory of Brabant.

1793 Campaign

Dumouriez Invades the Dutch Republic

The execution of the French king Louis XVI on January 21, 1793, made other European rulers even more worried. France officially declared war on Britain and the Netherlands on February 1, 1793. Soon after, many other countries joined the fight against France. The biggest and most important armies gathered near the border between France and Belgium. British Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger promised to pay for a large Austrian army and sent about 20,000 British troops under the Duke of York.

On February 16, 1793, Dumouriez's French army advanced from Antwerp and invaded Dutch Brabant. Dutch forces retreated. The Dutch leader asked Britain for help. British troops quickly arrived. Meanwhile, Austrian forces, now led by Saxe-Coburg, pushed back the French near Aldenhoven and took Aachen. They then reached Maastricht and forced the French to stop their siege there.

Coburg's victories pushed the French completely out of the Austrian Netherlands. This success reached its peak when Dumouriez was defeated at the Battle of Neerwinden on March 18. Dumouriez then switched sides and joined the Allies. He was replaced by General Picot de Dampierre. France was being attacked from many sides, and many thought the war would end quickly. However, the Allies didn't move fast enough. Instead of attacking Dampierre's weak army, the Austrians decided to besiege French fortresses along the border.

Coalition Spring Attacks

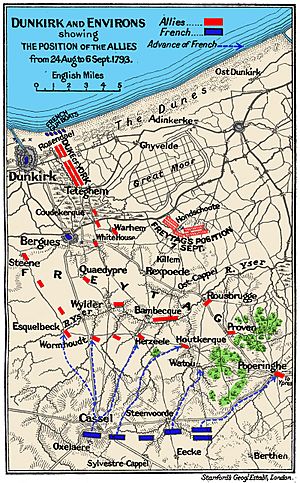

In April, the Allied leaders met to plan their strategy. The British wanted to capture Dunkirk as a prize of war. Coburg suggested attacking Condé and Valenciennes first, then Dunkirk.

On the Rhine front, the Prussians besieged Mainz and swept through the Rhineland, defeating small French forces. In Flanders, Coburg began attacking the French fortresses at Condé-sur-l'Escaut, now with help from British and Prussian troops. The French, under Dampierre, tried to relieve Condé but were defeated. Dampierre was badly wounded and died.

With the Duke of York's troops, Coburg's army grew to over 90,000 men. He then moved against Valenciennes. On May 23, York's British and Hanoverian forces fought their first battle at Famars. The French were pushed back, opening the way for the siege of Valenciennes. The new French commander, Adam Custine, needed time to reorganize his army and retreated. Both Condé and Valenciennes fell in July. Custine was then called back to Paris and put to death for not acting fast enough.

Autumn Battles

In August, the French were pushed back from Caesar's Camp near Cambrai. The Allies then split their forces. The Prussian troops left to join the main Prussian army. The Duke of York was ordered to besiege the French port of Dunkirk, which the British wanted as a military base. This caused problems with Coburg, who needed York's troops to protect his flank. Without York's support, the Austrians decided to besiege Le Quesnoy instead.

York's forces began the siege of Dunkirk, but they weren't ready for a long siege and didn't have heavy cannons. The French army, now led by Jean Nicolas Houchard, defeated York's forces at the Battle of Hondschoote. This forced York to give up the siege and leave his equipment behind. The British and Hanoverians retreated safely. Houchard's plan was to then march south to help Le Quesnoy. He defeated the Dutch at Menin, but then his forces were defeated by Beaulieu at Courtrai.

Further south, Coburg captured Le Quesnoy in September. He moved troops north to help York and won a victory at Avesnes-le-Sec. News also came that the Prussians had defeated the French in Alsace. The French government was in a panic. Houchard was accused of not following up his victory and was put to death in Paris.

At the end of September, Coburg began attacking Maubeuge. But York's army was weakened because Britain was sending troops to other places. So, Houchard's replacement, Jean-Baptiste Jourdan, was able to gather his forces. He narrowly defeated Coburg at the Battle of Wattignies, forcing the Austrians to stop their attack on Maubeuge. The French then tried to attack York's base at Ostend, but they were pushed back. This ended the fighting for the year.

1794 Campaign

Over the winter, both sides reorganized. Britain sent more troops to help the Coalition. The Allied army had over 100,000 soldiers. The French army, now led by Jean-Charles Pichegru, was much larger, with about 200,000 soldiers.

Siege of Landrecies

In April 1794, the Austrian Emperor Francis II joined Coburg, which encouraged the Austrian troops. The Allies began to attack the fortress of Landrecies. York's forces advanced, and the Hereditary Prince began the siege of Landrecies. The Allied army formed a semi-circle to protect the siege.

The French planned to attack both sides of the Allied army and send help to Landrecies. On April 24, British and Austrian cavalry pushed back a French force. Two days later, Pichegru launched a three-part attack to relieve Landrecies. Two of the French columns were defeated by Allied forces. The third column was almost completely destroyed by York at Beaumont on April 26.

French May Counter-Attack

Landrecies fell on April 30, 1794. Coburg then turned his attention to Maubeuge. But on the same day, Pichegru began his own attack in the north. He defeated Clerfayt at the Battle of Mouscron and recaptured Courtrai and Menen.

For 10 days, there was a break in fighting. Then, Coburg launched attacks to regain the northern positions on May 10. The French were defeated by York at the Willems, but Clerfayt failed to recapture Courtrai.

The Coalition planned a large attack to stop Pichegru. But at the Battle of Tourcoing on May 17-18, their plan failed badly. Communication broke down, and columns were delayed. Only a third of the Allied army fought, and they lost 3,000 men. Pichegru was not there, so Joseph Souham led the French at Tourcoing. When Pichegru returned, he continued to attack but was held off at the Battle of Tournay on May 22.

Meanwhile, Pichegru's attack on the Sambre River was also happening. French divisions tried to cross the river to capture Charleroi. Their goal was to cut off the Allied supply lines to Brussels.

The first French attempt to cross was stopped at the battle of Grand-Reng on May 13. A second attempt was defeated at the battle of Erquelinnes on May 24.

| French commanders |

|---|

|

|

Even though the Allied front was still holding, Austria's commitment to the war was weakening. Prussia was already thinking about leaving the war. The Emperor Francis II was influenced by his Foreign Minister, Baron Johann von Thugut, who cared more about politics than military plans. In May 1794, Thugut was focused on gaining land in Poland, so troops and generals were taken away from Coburg's command. Mack, Coburg's Chief of Staff, resigned. On May 24, Emperor Francis II called for a vote on withdrawing troops and then left for Vienna. Only the Duke of York disagreed with the withdrawal.

The decision to retreat was made even though the Allies had won some battles in the south. With the northern front temporarily stable, Coburg moved forces south. Pichegru then took advantage of the weakened Allied northern sector and began the Siege of Ypres on June 1. Clerfayt's counter-attacks were all pushed back by Souham.

On the Sambre front, the French decided to capture Charleroi as a base. They crossed the river a third time and besieged Charleroi. But on June 3, the Prince of Orange attacked them at the battle of Gosselies and forced them back across the Sambre.

Battle of Fleurus

At this time, the French were reinforced by four divisions under Jean-Baptiste Jourdan. Jourdan took command of the entire force and launched a fourth crossing and a second siege of Charleroi. At the battle of Lambusart on June 16, his advancing divisions ran into the Prince of Orange's troops in thick fog. The French were surprised and had to retreat.

The French army was not badly damaged. They crossed the Sambre again and attacked two days later, on June 18, surprising Coburg. On this day, Ypres surrendered to Pichegru. With no need to help Ypres, Coburg decided to focus most of his forces on the Sambre to push Jourdan back. He left York at Tournai and Clerfayt at Deinze to face Pichegru. However, Clerfayt was soon pushed back and retreated behind Ghent, forcing York to also retreat.

Charleroi surrendered to the French a day before Coburg's main Austrian force arrived to help. On June 26, Coburg attacked Jourdan at the Battle of Fleurus. Even though Jourdan's forces were pushed back at first, they managed to hold their ground and even counter-attacked. The battle didn't have a clear winner, but Coburg decided to withdraw after learning that Charleroi had been captured.

The Battle of Fleurus was a turning point. Historians believe that the Austrian court was already convinced that holding the Austrian Netherlands was not worth the effort. Coburg might have given up the chance of victory to pull his troops eastward.

With French gains in both the north and south, the Austrians called off the attack and retreated towards Brussels. This was the start of a general Allied retreat to the Rhineland and Holland. The Austrians almost completely gave up their control of the Austrian Netherlands, which they had held for 80 years.

Allied Retreat from Fleurus to Malines

The Allied forces were now split into two groups: the Duke of York's troops and the main Austrian and Dutch army under Coburg. They were still supposedly under Coburg's command, but they acted separately with their own goals. Coburg wanted to retreat east to protect Germany, while York wanted to retreat north to protect Holland.

Meanwhile, Pichegru's army had been threatening York's forces. But he was ordered to move to the coast and capture Flemish ports, then invade Holland. York was forced to retreat when the French captured Mons and Soignies, pushing Coburg eastward and leaving York's left side open.

York had evacuated all British garrisons during his retreat, except for Nieuport. The British Secretary of War had promised to evacuate them by sea, but this promise was not kept. Nieuport was besieged and captured on July 16. The French emigres (people who had fled France) in the garrison were killed.

On July 5, Coburg and York agreed to defend a line from Antwerp to Namur. However, the next day, Jourdan attacked along the line. Coburg canceled the agreement and retreated eastward, leaving Brussels. This exposed York's left side again.

On July 7 and 8, Jourdan attacked Coburg's left wing near Namur, forcing it back and isolating Namur. Coburg then retreated his entire army further, forcing York to also retreat.

The Allies were now spread out. York's 30,000 men guarded the Dyle River. The Prince of Orange's Dutch army defended from Malines to Louvain. Coburg's Austrians were on a line from Louvain to the Meuse River.

Pichegru occupied Brussels on July 10. Both his and Jourdan's armies marched through the city in victory parades.

Allied Retreat to Holland and the Meuse

| Allied commanders |

|---|

|

|

During this retreat, the Allies weren't heavily pressured. This was because Pichegru's army was sent to the Flemish coast. Jourdan was ordered to send 40,000 men to recapture the Austrian fortresses of Landrecies, Le Quesnoy, Valenciennes, and Condé.

On July 12, Pichegru advanced against Malines with 18,000 men. Jourdan advanced against Louvain and other towns. Pichegru easily captured Malines from York on the 15th. Jourdan captured Louvain the same day. Namur surrendered on July 19.

When Louvain was taken, the Dutch army retreated north towards their homeland instead of following the Austrians. At this point, the Dutch also started pursuing their own military goals, separate from Coburg's Austrian army. With his left side exposed again, York pulled his troops back. On July 18, York learned that Coburg had decided to withdraw his main force even further east, without even telling him.

Coburg's further retreat forced York to retreat north again. He evacuated Antwerp on July 22 and retreated across the Dutch border on July 24. On the same day, Coburg finally retreated across the Meuse River. This marked the final separation of British and Austrian forces. They were now pursuing completely different goals.

On July 27, the French captured Liège. They began to demolish Saint Lambert's Cathedral, which they saw as a symbol of old power.

Second Invasion of the Dutch Republic

In August 1794, there was a pause in fighting. The French focused on capturing Belgian ports. York tried to get Austrian support, but it was difficult. Under pressure from Britain, the Emperor dismissed Coburg. Clerfayt temporarily took his place. After the French captured Le Quesnoy and Landrecies, Pichegru renewed his attack on August 28. This forced York to retreat to the Aa River, where he was attacked at Boxtel and persuaded to withdraw to the Meuse. On September 18, Clerfayt was defeated at the Battle of Sprimont, and again at the Battle of Aldenhoven on October 2. This forced the Austrians to retreat to the Rhine, ending their presence in the Low Countries. Only the strong fortress of Luxembourg City remained, but it was besieged for seven months.

By autumn, the French, including Dutch Patriots, had taken Eindhoven. The Dutch Orangists surrendered 's-Hertogenbosch on October 12 after a three-week siege. York planned a counter-attack to help Nijmegen, but it was canceled when the Hanoverian troops pulled out. On November 7, Nijmegen was also given up to the French. York prepared to defend the Waal River line through the winter, but in early December, he was called back to England. In his absence, Hanoverian General Count von Walmoden took charge. At this stage, the Prussians were talking peace with the French. Britain's position in the Dutch Republic looked very insecure.

On December 10, troops under Herman Willem Daendels attacked Dutch defenses across the Meuse River, but they failed. However, in the following days, temperatures dropped sharply, and the Meuse and Waal rivers froze solid. This allowed the French to continue their advance. By December 28, the French had occupied more Dutch land. French brigades, including Dutch Patriots, moved easily through the frozen Dutch Water Line and captured towns and forts.

1795 Campaign

Fall of the Dutch Republic

When French troops crossed the frozen Waal River, British and Hessian forces counter-attacked successfully. But on January 10, Pichegru ordered a general advance across the frozen river. The Allies were forced to retreat behind the Lower Rhine. On January 15, the British and Hanoverian army withdrew from their positions and began a retreat towards Germany in a fierce blizzard. On January 16, the city of Utrecht surrendered.

Dutch revolutionaries led by Krayenhoff pressured the city council of Amsterdam to hand over the city. They did so just after midnight on January 18. This started a pro-French revolution in Amsterdam. Earlier that day, the Dutch leader William V, Prince of Orange and his followers had fled to England. Dutch revolutionaries declared the Batavian Republic on January 19. French troops entered the city and were cheered by the people. On January 24, the Capture of the Dutch fleet at Den Helder took place.

British Evacuation

The British continued their retreat northwards, poorly equipped and clothed. By spring 1795, they had left Dutch territory completely and reached the port of Bremen in Hanover. There, they waited for orders from Britain. Pitt, realizing that success on the continent was impossible, finally ordered them to withdraw back to Britain. They took the remaining Dutch, German, and Austrian troops with them. York's army had lost more than 20,000 men in two years. A small British force remained on the Continent until December 1795. The surrender of Luxembourg on June 7, 1795, marked the end of the French conquest of the Low Countries and the Flanders campaign.

What Happened Next

For the British and Austrians, the campaign was a disaster. Austria lost its territory, the Austrian Netherlands (modern Belgium and Luxembourg). Britain lost its closest ally in Europe, the Dutch Republic. It would be over twenty years before a friendly pro-British government was in power in The Hague again. Prussia also abandoned the Dutch leader and signed a separate peace with France in April, giving up its lands on the west side of the Rhine. The Coalition fell apart even more when Spain also made peace with France. Austria continued fighting but was defeated by French forces under Napoleon in Italy. Austria finally made peace in 1797, accepting the French control of the Netherlands.

In Britain, the Duke of York was often seen as an incompetent leader. However, some historians disagree, and his defeat didn't stop him from holding important military commands later.

There were several reasons why the Allies failed. The commanders had different and conflicting goals. There was poor coordination between the different nations. The troops faced terrible conditions. Outside politicians also interfered. Also, the French armies became more confident and flexible, while the Allied forces were more traditional and slow.

The campaign showed the weaknesses of the British army after years of neglect. The Duke of York then started a huge reform program. The Austrian army, while strong at times, was often too cautious.

Both Britain and Austria decided to stop focusing their main military efforts on the Low Countries. Britain decided to use its navy to attack French colonies in the West Indies. The Austrians made the Italian front their main defense line. Britain did try to invade the Batavian Republic again in 1799, again led by the Duke of York, but it failed.

Lasting Impact

In Britain, the nursery rhyme "The Grand Old Duke of York" is often linked to this campaign, though the rhyme existed much earlier.

For the British, the lessons learned in this campaign led to major army reforms. The strong, professional army that later fought in the Peninsular War was built on these lessons.

The Allies would not have such a good chance to defeat the new French government again until 1814. For Austria, losing the Austrian Netherlands put huge pressure on the Holy Roman Empire, leading to its collapse in 1806. French control of the Netherlands allowed its armies to go deep into Germany and later helped Napoleon create the Continental System. For the French, victory in the field helped stabilize their government at home.

Many officers who later became famous got their first battle experience in Flanders. These included several of Napoleon's marshals, like Bernadotte, Jourdan, Ney, MacDonald, Murat, and Mortier. For the Austrians, Archduke Charles got his first command there. In the Hanoverian army, Scharnhorst first fought under the Duke of York.

In the British Army, the most notable debut was Arthur Wellesley (the future Duke of Wellington). He joined the campaign in late 1794 and fought at the Battle of Boxtel. He used these experiences in his later successful campaigns in India and the Peninsular War.

Images for kids

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |