Siege of Dunkirk (1793) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Siege of Dunkirk (1793) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the French Revolutionary Wars | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 10,000 | 35,100 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1,000, 14 guns, 2 mortars | 2,000, 32 heavy guns | ||||||

The Siege of Dunkirk happened in the autumn of 1793. It was a battle where British, Hanoverian, Austrian, and Hessian soldiers tried to capture the French port city of Dunkirk. These different armies were working together as a "Coalition" against France during the French Revolutionary Wars.

The Coalition forces were led by Prince Frederick, Duke of York. They surrounded Dunkirk, hoping to make the French give up. However, after a big defeat at the Battle of Hondschoote, the Coalition had to stop their attack and leave.

Contents

The Attack on Dunkirk

The idea to attack Dunkirk didn't come from the military leaders. It came from the British government, especially Henry Dundas, a close advisor to William Pitt. Dundas thought having Dunkirk would be useful for future peace talks or as a British base in Europe.

However, some military experts thought attacking Dunkirk wasn't the best plan for winning the war. They believed it stopped the Duke of York from helping the main Allied army further inland.

Starting the Siege

Even so, the Duke of York followed his orders. In late August 1793, he quickly moved his troops towards Dunkirk. The French were surprised by his sudden move. On August 22, York led about 20,000 British, Austrian, and Hessian soldiers to surround Dunkirk. They pushed back the French soldiers and captured 11 cannons.

The first group of attackers, made up of Austrian soldiers, lost about 50 men. The French commander, Jean Nicolas Houchard, was very upset by his soldiers' retreat. He wrote that the soldiers were good, but their officers were "cowardly and ignorant."

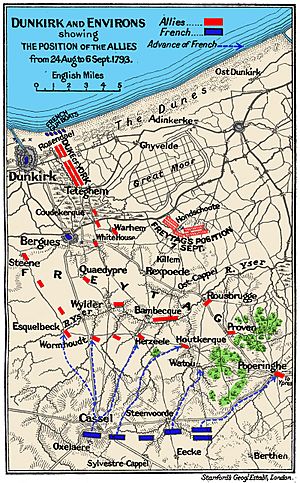

To protect York's left side, Heinrich Wilhelm von Freytag commanded 14,500 Hessian and Hanoverian troops. These soldiers spread out in villages south of Dunkirk.

French Defenses and Reinforcements

The French were indeed surprised, and Dunkirk's defenses were not in good shape. The town might have fallen quickly if the British navy had arrived on time. One witness even wrote that the town would have surrendered if officials from Paris hadn't arrived to stop it.

Back in Paris, Lazare Carnot and Pierre Louis Prieur joined the Committee of Public Safety. Carnot quickly realized that a British defeat at Dunkirk would be a huge blow. So, he ordered 40,000 soldiers from other areas to gather south of Dunkirk. These troops were meant to help the 5,000 defenders already inside the city, led by Joseph Souham.

On August 24, a group of 2,500 soldiers, led by Jean-Baptiste Jourdan, arrived to reinforce Dunkirk. This brought the city's defenders to nearly 8,000 men. Jourdan was later replaced by Leclaire, and with the help of Lazare Hoche, Souham worked hard to strengthen the city's defenses and boost the morale of his soldiers.

The First Attacks

On August 24, York's reserve troops, led by Austrian General Eduard d'Alton, attacked the suburb of Rosenthal. They pushed the French back inside the city walls. York reported that his soldiers were very brave and went too far, chasing the enemy right up to the city's defenses. This caused them to lose many men to cannon fire from the town.

Sadly, General d'Alton was shot and killed that day. York's army then started digging trenches in a line from Tetteghem to the sea.

Problems for the Attackers

Despite their initial confidence, York's army faced many problems. The British government had failed to send enough equipment for a siege, especially heavy cannons. These cannons were supposed to arrive by August 26, but only French gunboats showed up, firing at York's troops from the sea. On August 27, ships arrived with cannon crews, but still no cannons! On August 30, Admiral John MacBride arrived to help with naval operations, but he didn't have a fleet either.

Another worry for York was that the Dutch forces, led by the Prince of Orange, were pushed back near Menin on August 28. This created a gap between York's army and the main Austrian army further south. York had to send some of his cavalry to help the Dutch, even though he couldn't spare them.

York was in a very difficult spot. The French commander, Souham, opened the city's floodgates. This slowly flooded the fields between York's army and Freytag's troops, filling British trenches with two feet of water. The area became a swamp, and a sickness called "Dunkirk Fever" spread quickly among the soldiers.

York didn't have enough men to surround Dunkirk completely, so the French could always send in more soldiers. His right side was constantly attacked by French gunboats, and he still had no siege equipment. The British finally found some cannons by taking them from a ship at Furnes, and these arrived by canal on August 27.

York's Retreat

On September 6, the French commander Houchard led his forces from Cassel to attack Freytag's Hanoverian troops at the Battle of Hondshoote. On the same day, the French defenders in Dunkirk launched a strong attack to keep York's army busy. This attack focused on the Austrian troops on York's right side. After fierce fighting, the French were pushed back, but both sides suffered heavy losses. One of York's important engineers, Colonel James Moncrief, was killed that day.

On York's left side, Freytag's Hanoverian soldiers were eventually forced back to the town of Hondschoote. Freytag himself was wounded and briefly captured before being rescued. Johann Ludwig, Reichsgraf von Wallmoden-Gimborn took command of the troops. On September 8, Houchard attacked again and forced Wallmoden to retreat after a very tough fight.

With news that his left side was exposed, the Duke of York ordered his heavy supplies to be moved back to Veurne. Then, in a meeting on September 8, it was decided to give up the siege of Dunkirk. Souham had made the canal unusable for transport, so the British had to abandon their heavy naval cannons.

At 11:00 PM on September 8, York's army began to retreat towards the coastal city of Veurne in Belgium. They left behind much of their baggage because of bad weather and difficult terrain. They reached Furnes by 7:00 AM the next morning, where they met up with the rest of Wallmoden's troops. York then moved towards Diksmuide, leaving some soldiers behind in Veurne until September 14.

What Happened Next?

On September 11, Admiral MacBride's fleet finally appeared off Nieuport, but it was three weeks too late.

Out of about 35,100 Coalition soldiers involved, about 2,000 were killed or wounded. Many more got sick because of the swampy conditions. Some estimates suggest a total loss of 10,000 men, including those from the Battle of Hondschoote. The Coalition also left behind 32 cannons for the French.

The 8,000 French defenders suffered about 1,000 casualties. They also lost 14 cannons, two mortars, and some other supplies.

Why Did It Fail?

Historians have looked closely at why the Siege of Dunkirk failed. Alfred Burne points out several reasons, based on the Duke of York's own reports.

York believed there were three main reasons for the failure:

- First, the British government didn't keep its promises about providing supplies and support.

- Second, the plans of other Allied armies changed, which allowed the French to bring more soldiers against York and Freytag.

- Third, Freytag's own actions during the battle.

An officer wrote to a newspaper shortly after the Battle of Hondschoote that if the British navy's gunboats had been ready and if officers in England had supported the Duke of York, Dunkirk would have fallen easily. He blamed the government ministers for the losses.

Burne also noted something important: the French broke the rules of surrender at Valenciennes. The agreement said that prisoners released from Valenciennes shouldn't fight again. However, the French sent these very prisoners to reinforce Dunkirk. Burne believes that if the French hadn't done this, Dunkirk probably would have been captured.

Historian Digby Smith argues that Dunkirk was a missed chance. He blames the British government for insisting on this attack instead of properly supporting their Austrian allies against the main French armies.

However, Burne also suggests that even though attacking Dunkirk went against the idea of keeping all forces together, it's unlikely the Austrians would have marched on Paris without first capturing other towns. So, he thinks the British army was better off trying to take Dunkirk than helping the Austrians with other sieges.

| Ernest Everett Just |

| Mary Jackson |

| Emmett Chappelle |

| Marie Maynard Daly |