Brabant Revolution facts for kids

| Part of the Atlantic Revolutions | |

Scenes of the popular uprising at Ghent in support of the patriot army in November 1789

|

|

| Date | 24 October 1789 – 3 December 1790 (1 year, 40 days) |

|---|---|

| Location | Austrian Netherlands (modern-day Belgium) |

| Outcome |

|

The Brabant Revolution was an armed uprising in the Austrian Netherlands (which is now Belgium). It happened between October 1789 and December 1790. This revolution took place at the same time as the French Revolution and the Liège Revolution.

The Brabant Revolution briefly ended the rule of the Habsburg monarchy (the Austrian royal family). It led to the creation of a new, but short-lived, country called the United Belgian States.

This revolution started because people were unhappy with the changes made by Emperor Joseph II. His changes were seen as attacks on the Catholic Church and the old traditions of the Austrian Netherlands. People in areas like Brabant and Flanders especially resisted these changes.

After some unrest in 1787, many unhappy people went to the nearby Dutch Republic. There, they formed a rebel army. When revolutions started in France and Liège, this rebel army entered the Austrian Netherlands. They won a big victory against the Austrians at the Battle of Turnhout in October 1789.

With support from local uprisings, the rebels quickly took control of most of the region. They declared independence. In January 1790, they formed the United Belgian States. However, this new country didn't get much support from other nations.

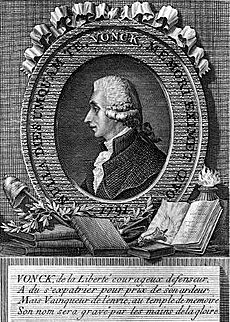

Soon, the rebels themselves split into two groups. The Vonckists, led by Jan Frans Vonck, wanted a more modern and liberal government. The Statists, led by Henri Van der Noot, wanted to keep old traditions and had strong support from the Church. The Statists were more popular and eventually forced the Vonckists to leave the country.

By mid-1790, Austria was ready to stop the revolution. The new emperor, Leopold II, offered to forgive the rebels. But after the Statists lost a battle at Battle of Falmagne, Austrian forces quickly took back control. The revolution ended in December 1790. However, Austrian rule didn't last long, as French armies took over the area a few years later during the French Revolutionary Wars.

Contents

Why the Revolution Started

Austrian Rule in the Netherlands

The Austrian Netherlands was a region with its capital in Brussels. It covered much of what is now Belgium and Luxembourg. In 1714, this land, which used to be ruled by Spain, was given to Austria.

The people in the Austrian Netherlands were mostly Catholic. The Church had a lot of power there. This region was part of the larger Holy Roman Empire, which was a group of many smaller, mostly independent territories in Central Europe.

In 1764, Joseph II became the Holy Roman Emperor. He believed in "enlightened absolutism." This meant he wanted to rule with total power but also use new, modern ideas from the Age of Enlightenment. Joseph II thought many old traditions were outdated. He especially disliked the Catholic Church's strong ties to the Pope, as this limited his own control.

In 1781, Joseph II visited the Austrian Netherlands. He decided that many changes were needed there. The Austrian Netherlands had many self-governing areas, like the Estates of Brabant and Flanders. These areas had kept much of their traditional power. The Austrian governors had to respect these local powers.

Emperor Joseph II's Reforms

Joseph II wanted to make his lands more efficient and easier to govern. Starting in 1784, he began making many big changes in how things were run. These changes affected the economy, government, and religion. Some people compared his actions to those of Philip II, who also tried to change local traditions. Like Philip, Joseph's changes upset many different groups of people.

His first changes targeted the Catholic Church. He saw the Church as a possible threat because it was loyal to the Pope.

- In 1781–82, he issued the Edict of Tolerance. This law gave more rights to non-Catholics. Catholics were very unhappy because it reduced their special status.

- He closed 162 monasteries where monks and nuns spent all their time in prayer.

- In 1784, he made marriage a civil event, not just a religious one. This reduced the Church's power over family life.

- In 1786, he closed all old training schools for priests. He created one state-run school in Leuven. This school would teach a new, state-approved type of theology.

Joseph also tried to change the way the government worked.

- In 1787, he created a new, more centralized system. He replaced many old local government bodies with a single General Council.

- He also created nine new administrative areas, each controlled by an Intendant. These new officials took power away from the local states.

- He changed the justice system. He replaced old local courts with a central system. A single Sovereign Council of Justice was set up in Brussels.

These changes threatened the independence of the local states, the power of the nobles, and the position of the Church. This caused these different groups to unite against the Austrian government.

Growing Opposition and the Small Revolution

Joseph's changes were very unpopular. Most people, especially those influenced by the Church, felt these changes threatened their traditions. Even some who liked new ideas thought the reforms didn't go far enough. People in Hainaut, Brabant, and Flanders were especially against the changes.

Lawyer Henri Van der Noot spoke for the Estate of Brabant. He said the reforms broke the rules of the Joyous Entry of 1356. This was an old agreement that protected the region's rights.

In 1787, there were many protests and riots, known as the Small Revolution. The government used local militias to stop them. But this showed that the Austrian army alone couldn't keep order without public support. The militias, who called themselves Patriots, were also starting to feel uncertain.

The governors temporarily stopped the reforms in May 1787. They asked people to send in their complaints. But this only made critics even angrier. Emperor Joseph II was furious. He eventually agreed to cancel his changes to the government and justice system. But he kept his Church reforms. He hoped this would divide the opposition, but it didn't work.

Between 1788 and 1789, the Austrian government decided to force the reforms through. Some local states refused to pay taxes. The Joyous Entry agreement was officially cancelled, and the Estates of Hainaut and Brabant were shut down.

Organized Resistance and the Émigrés

After the Small Revolution, opposition became more organized. Van der Noot, a key organizer, went to the Dutch Republic. He tried to get support from William V to overthrow the Austrians. But William V was not interested.

Still, Van der Noot set up a base in Breda, near the Dutch-Belgian border. Many unhappy people from Flanders and Brabant fled to the Dutch Republic to join his growing "émigré" (exile) army.

Inside the Austrian Netherlands, lawyers Jan Frans Vonck and Verlooy formed a secret group called Pro Aris et Focis in 1789. They planned an armed uprising. Most members were lawyers, writers, and merchants. They were supported by the clergy. Vonck believed that Belgium should free itself, not rely on foreign help.

All the opposition groups, including Van der Noot, agreed to unite. They formed the Brabant Patriot Committee. They decided the rebellion would start in October 1789. Jean-André van der Mersch, a retired military officer, was chosen to lead the rebel army in Breda.

The Revolution Begins

In the spring of 1789, the French Revolution began in France. In August 1789, people in the Prince-Bishopric of Liège also overthrew their ruler in a peaceful uprising. This was called the "Happy Revolution." Many people saw these events as revolutionary ideas spreading from France. The Prince-Bishop fled, and the revolutionaries declared a republic in Liège.

The Invasion

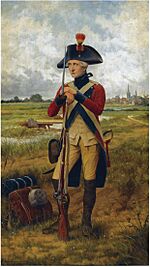

The Brabant Revolution officially began on October 24, 1789. The rebel army, led by Van der Mersch, crossed into the Austrian Netherlands from the Dutch border. This army had about 2,800 men.

In the town of Hoogstraten, they read a special document called the Manifesto of the People of Brabant. This document said that Joseph II was no longer a rightful ruler. The text was similar to an old Dutch declaration from 1581 that rejected Spanish rule.

On October 27, the rebel army fought a larger Austrian force near Turnhout. The battle was a big victory for the rebels, even though they were outnumbered. This defeat badly weakened the Austrian forces in Belgium. Many local soldiers in the Austrian army left to join the rebels.

With new recruits and public support, the rebel army quickly moved into Flanders. On November 16, they captured Ghent, a major city, after four days of fighting. The rebel armies continued to advance, winning small battles. By December, the Austrian forces had retreated to Luxembourg, leaving the rest of the territory to the patriots.

Historians note that the rebels' entry into the Austrian Netherlands was similar to an event in 1566 that started the Dutch Revolt against Spanish rule.

The United Belgian States

After the Austrian government fell, the revolutionaries had to decide what kind of new country to create. Some people in France encouraged them to declare independence, like the American Revolution. On November 30, Flanders and Brabant signed a Declaration of Unity. On December 20, they signed a declaration of independence, ending Austrian rule.

After Brussels was captured on December 18, work began on a new constitution. In January, the rebels called back the States-General. This was an old assembly of provincial leaders that hadn't met since the Middle Ages. Its 53 members met in Brussels to discuss the new state.

The new constitution was inspired by both the Dutch declaration of 1581 and the American Declaration of Independence of 1776. However, liberals were unhappy that only the old powerful groups (guilds, clergy, nobility) were consulted. They felt the closed meetings of the States-General ignored the idea of popular rule.

On January 11, 1790, the United Belgian States was officially formed. The delegates agreed to unite the states into one country. A Sovereign Congress was created in Brussels to act as a parliament. However, most important decisions were still made by the individual states.

Growing Divisions Among Rebels

Soon after the United Belgian States was formed, two main groups emerged.

- The Vonckists, led by Vonck, were a liberal group. They believed the revolution meant that the people should have power. They were supported by the middle classes. They mostly agreed with Joseph's reforms but disliked how they were forced on the people. Their support was strong in Flanders.

- The Statists, led by Van der Noot, were more conservative. They had wider support from the clergy, lower classes, nobles, and old trade groups. They saw the revolution as a way to stop unwanted changes. Most Statists wanted to keep the old noble privileges and the Church's power.

These two groups soon argued over how the provincial assemblies should be set up. The Statists accused the Vonckists of having similar ideas to the radical French revolutionaries. By March 1790, the Statists had forced the Vonckists out of Brussels. In June, a large group of peasants, led by priests, marched on Brussels to support the Statists. They believed the Vonckists were against the Church, which was probably not true.

Van der Noot and the Statists began to persecute the Vonckists. This was called the Statist Terror. Vonck and his supporters were forced to leave the country and went to Lille. Many exiled Vonckists felt it would be better to negotiate with the Austrians than with the Statists. The Statists hoped for foreign military help, especially from Prussia.

The Revolution is Stopped

In December 1789, the Liège Republic was condemned by the Austrians. Prussian troops occupied it, but later withdrew, and the revolutionaries took power again.

The Brabant Revolution continued for a while because Austria was busy. Joseph II was ill, and the main Austrian army was fighting the Ottoman Empire. The only Austrian forces in the region were hiding in Luxembourg.

The Statists tried to get foreign support for the United Belgian States, but they failed. The Dutch were not interested. The Prussian king, Frederick William II, sent some troops in July, but he was forced to withdraw them by Austria and Britain.

Joseph II died in February 1790. His brother, Leopold II, became the new emperor. Leopold made peace with the Turks and sent 30,000 troops to stop the rebellion in Brabant. On July 27, 1790, Leopold signed an agreement with Prussia. This allowed him to take back the Austrian Netherlands, as long as he respected its local traditions. He offered to forgive all revolutionaries who surrendered.

The Austrian army, led by Blasius Columban, Baron von Bender, invaded the United Belgian States. They faced little resistance because people were already unhappy with the rebels' government and their infighting. The Austrians defeated the Statist army at the Battle of Falmagne on September 28.

Hainaut was the first to accept Leopold's rule, and other cities soon followed. Namur was captured on November 24. The Sovereign Congress met for the last time on November 27. On December 3, the Austrians took back Brussels. This marked the end of the revolution.

What Happened Next

After the United Belgian States was defeated, a meeting was held in The Hague in December 1790. They decided to cancel most of Joseph II's reforms. However, people continued to write anti-government pamphlets. The Liège Revolution was also stopped by Austrian forces in January 1791.

French Invasion

The Vonckists who had been exiled in France supported a French invasion. They saw it as the only way to achieve their goals. After both Belgian revolutions were crushed, some Brabant and Liège revolutionaries met in Paris. They formed a group called the Committee of United Belgians and Liégeois. They even raised Belgian and Liège armies to fight with the French against the Austrians.

France declared war on Austria in April 1792. The French army defeated the Austrians at the Battle of Jemappes in 1792. They briefly took over the Austrian Netherlands and Liège. But the Austrians pushed them out after the Battle of Neerwinden in 1793.

In June 1794, French revolutionary troops finally drove the Austrians out of the region after the Battle of Fleurus. In October 1795, the French government officially took over the territory. It was divided into nine French départements. French rule brought many changes, like legal equality and separating church and state.

Legacy of the Revolution

After Napoleon's defeat in 1815, Belgium came under Dutch rule. The Belgian Revolution of 1830, which led to Belgium's independence, was partly inspired by the Brabant Revolution.

On the day the 1830 revolution started, revolutionaries began flying a new flag. Its colors (red, yellow, and black) were clearly influenced by the colors chosen during the Brabant Revolution of 1789. These colors are now the national flag of Belgium. Some historians also believe that the Vonckists and Statists were early versions of the main political parties in independent Belgium: the Liberals and the Catholics.

See also

- Patriottentijd (c.1780–87) – political unrest in the Dutch Republic around the same time

- Peasants' War (1798)

- Belgium in the long nineteenth century

- List of revolutions and rebellions

Images for kids

-

Map of the Austrian Netherlands in the 1780s. The region was not connected and was split by the Prince-Bishopric of Liège and the tiny Duchy of Bouillon.

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |