Liège Revolution facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Liège Revolution |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Atlantic Revolutions | |||||||

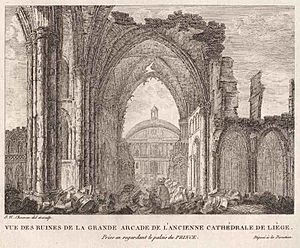

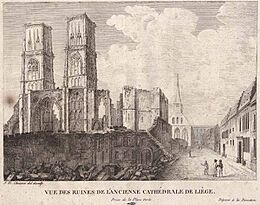

Destruction of the Cathedral of Saint-Lambert by revolutionaries. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Supported by: |

Supported by: |

||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

The Liège Revolution was a big uprising against the ruler of Liège, the prince-bishop. It started on August 18, 1789, and ended when Austrian forces took back control in 1791. This revolution happened at the same time as the French Revolution. It changed Liège forever, leading to the end of the Prince-Bishopric and Liège becoming part of France in 1795.

Contents

Key Events of the Liège Revolution

- 985: The Holy Roman Emperor, Otto II, makes the bishop of Liège a prince. This creates the Prince-Bishopric of Liège, a new state.

- 1772: Velbrück becomes prince-bishop. He supports new ideas and arts until he dies in 1784.

- 1784: Hoensbroeck takes over. He is much stricter and less open to change than Velbrück.

- 1789: Revolutions begin in Paris and Liège. Hoensbroeck runs away to Germany. The Liège Republic is declared.

- 1791: The Austrian army puts Hoensbroeck back in charge. Many supporters of the Republic go to Paris.

- 1792: Hoensbroeck dies. French troops take control of Liège after a big battle.

- 1793: Liège citizens vote to join France. But the Austrians win a battle and put a prince-bishop back in power.

- 1794: The French win more battles and take back Liège.

- 1795: France officially makes Liège part of its country.

Why People Were Unhappy (1684–1789)

How Liège Was Governed

For a long time, the prince-bishop of Liège was supposed to rule with the help of three groups: the church leaders, the nobles, and the common people (middle classes and workers). However, the system was unfair. The prince-bishop and the church leaders had most of the power.

The common people had very little say in how things were run. Many workers and peasants were very poor and couldn't find jobs. This made them want big changes in society and politics.

New Ideas from the Enlightenment

During the 1700s, thinkers had different ideas about Liège. Some thought it was like a free republic, where people had a say. Others saw the bishop's power as unfair, like a tyrant.

For example, the writer chevalier de Jaucourt said Liège had "32 artisans' colleges, who take some part in the government." But he also noted that "its number of churches, abbeys and monasteries considerably oppress it."

On the other hand, Voltaire strongly criticized Liège's government. He believed that church leaders should serve the people, not rule over them. He said it was wrong for a bishop to act like a prince.

Velbruck: A Step Towards Modern Ideas

When François-Charles de Velbruck became prince-bishop in 1772, he wanted to bring new ideas to Liège. He was open to philosophers and new ways of thinking. He was like other "enlightened rulers" of his time.

Velbruck encouraged arts and sciences. He opened an academy for painting and sculpture. He also started the "Société libre d'Émulation" where smart people could meet and share ideas. Many future revolution leaders came from these groups.

He also tried to help the poor and make taxes fairer. He set up hospitals and free courses for midwives. He wanted everyone, rich or poor, boys or girls, to get an education. He even planned a big public library. But he didn't always have enough money or power to make all his ideas happen.

Growing Unrest and Economic Problems

After Velbruck died, César-Constantin-François de Hoensbroeck became prince-bishop in 1784. He was against any changes and wanted to bring back old privileges for the church and nobles. He didn't care about the common people's problems. People called him "the tyrant of Seraing" because he was so unpopular.

Liège's population grew a lot, especially young people. This added to the problems. The middle classes were very angry because the rich nobles and church leaders didn't have to pay taxes. In 1787, a leader named Fabry suggested taxing the rich instead of the poor. He also said the city's money was being wasted.

People started to demand more freedom and a government where they had a say. A future revolutionary, Jean-Nicolas Bassenge, wrote that people are free "when sovereignty, legislative power, resides in the whole nation." He meant that the power should belong to all the people, not just one ruler.

Even some nobles started to disagree with the prince-bishop. Revolutionary messages spread, saying things like:

- "Trample down slavery now."

- "No more tax if you have no representation."

- "You shall never pay to fatten the lazy."

- "You shall boldly suppress all its useless members."

- "You will radically cut the claws of the lawyers."

At this time, many people in both cities and the countryside were suffering. Bread prices were high, and many people had no jobs. In some towns, a quarter of the people were unemployed. Farmers also had problems with taxes and rich landowners. To make things worse, much of the food grown in Liège was sold to other countries, making the famine worse at home.

Meanwhile, in the nearby Austrian Netherlands, the ruler, Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor, made changes to reduce the church's power. He allowed different religions and civil marriage. These changes, even though they caused a revolution in the Austrian Netherlands, made people in Liège want similar freedoms.

The Spa Gambling Dispute

In the 1700s, the town of Spa was a famous resort where rich people came to relax and gamble. It was known as the "café de l'Europe." In 1763, the first modern casino, La Redoute, opened there.

Later, a nobleman named Noel-Joseph Levoz built a third gambling house in 1785. This caused a big fight because the other casinos had special permission from the prince-bishop. Levoz said their special rights were unfair.

Prince-bishop Hoensbroeck sent soldiers to close Levoz's casino. This event, and the long legal battle that followed, made many people even more angry at Hoensbroeck. When the French Revolution started in July 1789, it gave the people of Liège the final push to begin their own revolution.

The Revolution Unfolds

Revolution and Republic (1789–1791)

On August 18, 1789, Jean-Nicolas Bassenge and other leaders met in the city hall. They demanded that the old leaders be removed and replaced by popular mayors, Jacques-Joseph Fabry and Jean-Remy de Chestret. The rebels took over a fort, and Hoensbroeck was forced to agree to the changes.

But Hoensbroeck tricked them. A few days later, he ran away to Germany. The Holy Roman Empire said the Liège Revolution was wrong and ordered the old system to be put back.

However, the rebels in Liège went even further than France at first. They got rid of the prince-bishopric and created a republic. They wrote a new constitution that said everyone should pay equal taxes, people should elect their leaders, and everyone should be free to work. They also adopted a "Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen of Franchimont." This was like France's declaration but had some key differences. For example, it said that power belonged to the people, not just the nation.

From late 1789 to early 1790, Prussian soldiers occupied Liège. They tried to find a peaceful solution between the rebels and Hoensbroeck, but it didn't work. Hoensbroeck refused to compromise. Then, Leopold II, Holy Roman Emperor sent his Austrian army to put the prince-bishop back in power.

First Return of the Prince-Bishop (1791–1792)

Liège's volunteer soldiers, singing their song "Valeureux Liégeois", couldn't stop the powerful Austrian army. The Austrians entered Liège on January 12, 1791. Hoensbroeck got his throne back. He punished the revolutionaries, taking their property and forcing many to flee to France. These exiles later became strong supporters of the French Revolution.

Hoensbroeck's harsh rule made him even more hated. He died on June 3, 1792. François-Antoine-Marie de Méan became the new prince-bishop. Soon after, France, which was already fighting Austria and Prussia, ended its own monarchy. The war spread to Belgium, including Liège.

First French Control (1792–1793)

On November 6, 1792, the French general Dumouriez defeated the Austrians in the battle of Jemappes. He entered Liège on November 28, and the people were very excited. The Liège leaders who had been exiled returned with the French army. The prince-bishop, François-Antoine-Marie de Méan, fled. The French helped set up a new assembly where all men could vote.

Voting to Join France

With the French present, political groups started up again. These groups played a big part in getting Liège to vote to join France. People felt that Liège, having broken away from the Holy Roman Empire, had no choice but to join France to avoid being crushed by the Austrians.

The elections were open to all men aged 18 and older. Many people voted in Liège. In the city of Liège, 9,700 people registered to vote, which was about half of all eligible voters. Most voted "yes" to join France. Only 40 voted "no." This showed strong support for joining France, even though voting was not required. Many who opposed joining probably just didn't vote.

The vote showed that many people in Liège wanted to join France. This was partly because of the long history of conflict between the old system and the new ideas of the Republic.

Second Return of the Prince-Bishop (1793–1794)

In March 1793, the French army lost a battle at Neerwinden. The Austrians then put the prince-bishop back in charge. But this didn't last long. On June 26, 1794, French troops defeated the Austrians at Fleurus. On July 27, 1794, the Austrian troops left Liège after bombing and burning part of the city. The last prince-bishop, François-Antoine-Marie de Méan, went into exile for good. The battle of Sprimont on September 17 was the last battle before Liège was fully taken by the French.

Liège Becomes Part of France (1794–1815)

The first time the French were in Liège (1792–1793), people hoped Liège could be independent. But after the battles, people realized that being alone was dangerous. So, when the French came back in 1794, the idea of independence quickly faded. Liège was seen as conquered land.

In 1795, France officially annexed Liège. It was divided into three new areas called departments. These new departments were loyal to France. This was confirmed in 1801 by an agreement between Napoleon and pope Pius VII. Napoleon even visited Liège in 1803. Liège remained part of France until 1814. After Napoleon's defeat, the major powers decided that Liège would become part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands.

How Historians See the Revolution

Some historians, like Hervé Hasquin, believe the Liège Revolution was very similar to the French Revolution. They think it was even part of the French Revolution. They see it as a long process that ended in 1795 when Liège became part of France. During this time, the revolutionaries even destroyed the Saint-Lambert Cathedral. For the first time, all men in Liège could vote.

Other historians see the revolution as only happening when the prince-bishop was away, from August 1789 to February 1791. They see it as a separate event, like the Brabant Revolution in the Austrian Netherlands. However, the Liège Revolution wanted big changes to society and politics, just like the French Revolution. The Brabant Revolution, on the other hand, was against changes. The Liège Revolution led to Liège joining France, so its people didn't take part in the Brabant Revolution.

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |