Pim Fortuyn facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Pim Fortuyn

|

|

|---|---|

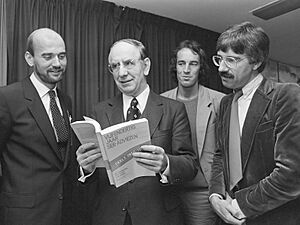

Fortuyn on 4 May 2002, two days before his assassination

|

|

| Born |

Wilhelmus Simon Petrus Fortuijn

19 February 1948 Velsen, Netherlands

|

| Died | 6 May 2002 (aged 54) Hilversum, Netherlands

|

| Cause of death | Assassination (gunshot wounds) |

| Resting place | San Giorgio della Richinvelda, Italy |

| Other names | Pim Fortuijn |

| Alma mater | VU Amsterdam (Bachelor of Social Science, Master of Social Science) University of Groningen (PhD) |

| Occupation | Politician · civil servant · Sociologist Corporate director · Political consultant · Political pundit · Author · Columnist · Publisher · Teacher · professor |

| Political party | Labour Party (1974–1989) People's Party for Freedom and Democracy (mid 1990s) Livable Netherlands (2001–2002) Livable Rotterdam (2001–2002) Pim Fortuyn List (2002) |

| Signature | |

|

|

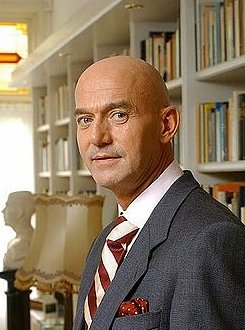

Wilhelmus Simon Petrus Fortuijn, known as Pim Fortuyn (Dutch: [ˈpɪɱ fɔrˈtœyn] (![]() listen); 19 February 1948 – 6 May 2002), was a Dutch politician, writer, and professor. He also worked as a civil servant and businessman. In 2002, he started his own political party called the Pim Fortuyn List (Lijst Pim Fortuyn or LPF).

listen); 19 February 1948 – 6 May 2002), was a Dutch politician, writer, and professor. He also worked as a civil servant and businessman. In 2002, he started his own political party called the Pim Fortuyn List (Lijst Pim Fortuyn or LPF).

Before entering politics, Fortuyn was a professor at Erasmus University of Rotterdam. He also worked as a business consultant and advised the Dutch government on social projects. Later, he became well-known in the Netherlands as a newspaper columnist and a commentator in the media.

Fortuyn's political views changed over time. In the 1970s, he was a member of the Labour Party. But in the 1990s, his ideas shifted, especially concerning immigration policies in the Netherlands. He openly shared his views on multiculturalism, immigration, and Islam in the Netherlands. He believed that if it were legally possible, the borders should be closed to Muslim immigrants. Fortuyn also wanted stronger actions against crime and less government rules. He was also openly gay and supported gay rights.

Fortuyn did not like being compared to "far-right" politicians from other countries. He saw his own politics as similar to centre-right leaders. He also admired some social democratic leaders. Fortuyn described his party's ideas as practical, not just popular. In March 2002, his new party, LPF, became the biggest party in his hometown of Rotterdam during local elections.

Fortuyn was killed during the 2002 Dutch national election campaign. He was shot by Volkert van der Graaf, an environmental and animal rights activist. Van der Graaf said he killed Fortuyn to stop him from using Muslims as "scapegoats" and targeting "weak people" to gain power. After Fortuyn's death, the LPF still came in second place in the election, but the party declined soon after.

Contents

Pim Fortuyn's Life and Career

Early Life and Education

Wilhelmus Simon Petrus Fortuijn was born on 19 February 1948. He grew up in Driehuis, a town in the Netherlands. He was the third child in a middle-class Catholic family. His father was a salesman, and his mother was a housewife.

Fortuyn went to Mendelcollege secondary school in Haarlem. He was known as a very smart student. When he was young, Fortuyn first wanted to become a priest. But in 1967, he started studying sociology at the University of Amsterdam. After a few months, he moved to the Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam. He finished his studies in 1971. In 1981, he earned a doctorate degree in sociology from the University of Groningen.

Professional Work

Fortuyn worked as a teacher at the Nyenrode Business Universiteit. He was also a professor at the University of Groningen, where he taught sociology. He wrote columns for the Groningen University Newspaper. At this time, he was interested in Marxist ideas and supported the Communist Party, but he never officially joined. Later, he became a member of the Labour Party.

In 1989, Fortuyn became a director of a government group that managed student transport cards. He also advised the Social and Economic Council (SER). In 1990, he moved to Rotterdam. From 1991 to 1995, he was a special professor at the Erasmus University Rotterdam. He also ran a business that advised on education.

After his teaching contract ended, he focused on public speaking and writing. He wrote books and newspaper columns, including a weekly column for Elsevier. He started appearing on TV debate shows often. His lively and confident speaking style made him a well-known public figure. In 1994, he started his own radio show. He also appeared on political debate shows and later as a commentator on a business news program. Fortuyn was openly gay and said in a 2002 interview that he was Catholic.

Political Journey

Fortuyn started his political journey with left-wing ideas. He disliked the traditional Dutch political system. He was interested in communist ideas but did not join any communist groups. In the 1970s, he joined the Labour Party and became a social democrat. By 1986, his views changed towards neoliberalism. He hoped that a free market would give people more freedom and reduce government control. In 1991, he suggested cutting the number of civil servants in half. He also supported making government services private and giving more power to local areas.

In 1992, Fortuyn wrote a book called Aan het volk van Nederland ("To the people of the Netherlands"). In this book, he presented himself as a modern version of an important 18th-century Dutch politician. The book encouraged people to use the free market to gain economic freedom from the welfare state. In 1989, Fortuyn left the Labour Party. In the 1990s, he joined the centre-right VVD. He also briefly advised the Christian Democratic Appeal party in the early 2000s.

While Fortuyn remained a neoliberal on economic issues, his cultural views changed. He became influenced by a political writer named Hendrik Jan Schoo. Schoo believed that a new group of progressive thinkers had promoted multiculturalism. In his 1995 book De verweesde samenleving ("The orphaned society"), Fortuyn argued that the progressive movements of the 1960s had weakened traditional values. However, Fortuyn did not want to return to old social rules. He believed that media, schools, and artists should guide society and promote modern Western values. Fortuyn always kept his liberal views on topics like LGBT rights throughout his political career.

Fortuyn believed that a country's identity could be defined by its differences from an "enemy." Influenced by the idea of a "clash of civilizations," he suggested that Islam could be seen as this new challenge after the fall of communism. In his 1997 book Tegen de islamisering van onze cultuur ("Against the Islamisation of our culture"), Fortuyn argued that the rise of religious fundamentalism was a reaction to the uncertainties of globalisation. He felt that the Dutch should protect their own culture, especially modern and Enlightenment values. He called for a "Cold War" against Islam, meaning a non-military defense. The September 11 attacks and the "War on Terror" made Islam a major topic in Dutch politics.

In 2001, Fortuyn announced on TV that he wanted to run for parliament. He was in contact with the new Livable Netherlands (LN) party. He was chosen as the lead candidate for LN on 26 November 2001, before the 2002 general election. In his campaign, Fortuyn criticized mainstream parties on multiculturalism, immigration, and law and order. He also called for less government involvement and changes to the healthcare and education systems. His slogan became "At your service!" Support for LN grew quickly under his leadership.

On 9 February 2002, Fortuyn gave an interview to a Dutch newspaper. His statements about immigration and Islam were very controversial. The Livable Netherlands party removed him as their lead candidate the next day. Fortuyn had said he wanted to close borders to Muslim immigrants. He also said he would, if legally possible, change the part of the Dutch constitution that forbids discrimination.

Starting the LPF Party

After being dismissed by Livable Netherlands, Fortuyn started his own party, the Pim Fortuyn List (LPF), on 11 February 2002. Many former Livable Netherlands members and supporters joined him. He led the local Livable Rotterdam party, which was like the LPF for Rotterdam. In the Rotterdam local elections in March 2002, his party won a huge victory. They won about 36% of the seats, becoming the largest party in the city council. For the first time since World War II, the Labour Party was not in power in Rotterdam.

Fortuyn's victory led to many interviews over the next three months. He made many statements about his political ideas. In March, he released his book The Mess of Eight Purple Years (De puinhopen van acht jaar Paars). This book criticized the Dutch political system and served as his plan for the upcoming national election. "Purple" referred to the government at the time, which was a mix of left-wing and conservative-liberal parties.

On 14 March 2002, Fortuyn was hit in the face with a pie by a left-wing activist. After this, Fortuyn became worried about being hurt or killed. He accused some Dutch politicians of encouraging violence against him.

Pim Fortuyn's Death

On 6 May 2002, Pim Fortuyn was killed in Hilversum, Netherlands. He was 54 years old. The attack happened in a car park outside a radio studio, where Fortuyn had just finished an interview. This was nine days before the national election, in which he was running. His driver, Hans Smolders, chased the attacker, Volkert van der Graaf. Police arrested Van der Graaf shortly after, and he still had the gun.

Months later, Van der Graaf admitted in court that he had killed Fortuyn. This was the first major political assassination in the Netherlands since 1672. On 15 April 2003, Van der Graaf was found guilty and sentenced to 18 years in prison. He was released on parole in May 2014, after serving two-thirds of his sentence, which is standard in the Dutch legal system.

Fortuyn's death shocked many people in the Netherlands. It highlighted the cultural differences within the country. After his murder, various conspiracy theories appeared. The assassination deeply affected Dutch politics and society. Politicians from all parties stopped campaigning. After talking with the LPF, the government decided not to delay the elections. Because Dutch law did not allow changing the ballots, Fortuyn remained a candidate even after his death.

The LPF had a very strong first election, winning 26 seats (17% of the 150 seats) in the House of Representatives. The LPF joined a government with the Christian Democratic Appeal and the People's Party for Freedom and Democracy. However, disagreements within the LPF quickly caused the government to fall apart, leading to new elections. By the next year, the party had lost support. They won only eight seats in the 2003 elections. In the 2006 elections, they won no seats. Around this time, the Party for Freedom, led by Geert Wilders, emerged as a new political force.

In his last months, Fortuyn became closer to the Catholic Church. A priest named Father Louis Berger often joined him in his last TV appearances. According to The New York Times, Berger became his "friend and confessor" in the weeks before his death.

Burial

Fortuyn was first buried in Driehuis in the Netherlands. On 20 July 2002, he was re-buried in San Giorgio della Richinvelda, Italy. He owned a house there.

Fortuyn's Ideas

Views on Islam and Immigration

When asked why he opposed Muslim immigration, Fortuyn said, "I have no desire to go through the emancipation of women and homosexuals all over again." In August 2001, he was quoted saying, "I am also in favour of a cold war with Islam. I see Islam as an extraordinary threat, as a hostile religion." On a TV show, Fortuyn said that Muslims in the Netherlands did not accept Dutch society. He believed that Islam was not compatible with Western values. He stated that Muslims in the Netherlands needed to accept living together with the Dutch. If this was not acceptable, he believed they were free to leave. He concluded by saying, "... I want to live together with the Muslim people, but it takes two to tango."

Fortuyn also said he did not object to Muslim immigrants because of their race. He was not against a multi-racial society. Instead, he opposed what he saw as a lack of integration. He felt they were unwilling to adapt to Dutch standards of modernity and social liberalism.

On 9 February 2002, more of his statements appeared in the Volkskrant newspaper. He said that the Netherlands, with 16 million people, had enough inhabitants. He believed that allowing 40,000 asylum-seekers into the country each year had to stop. (The actual number for 2001 was 27,000). He claimed that if he joined the next government, he would have strict immigration policies. He also wanted to grant citizenship to many illegal immigrants already living there.

Fortuyn believed that freedom of speech (Article 7 of the constitution) was more important than the article that forbids discrimination (Article 1). He said that all people already living in the Netherlands could stay. But, immigrants had to accept Dutch society's human rights values. He stated: "not integrating means leaving" and "the borders have to be hermetically closed." He also said, "If it were legally possible, I'd say no more Muslims will get in here." He claimed that the arrival of Muslims would threaten freedoms in liberal Dutch society. He thought Muslim culture had not gone through a modernization process. Therefore, he believed it still lacked acceptance of democracy and the rights of women, gay people, and minorities.

When asked by the Dutch newspaper Volkskrant if he hated Islam, he replied: "I don't hate Islam. I consider it a backward culture. I have traveled much in the world. And wherever Islam rules, it's just terrible. All the hypocrisy. It's a bit like those old Reformed Protestants. The Reformed lie all the time. And why is that? Because they have standards and values that are so high that you can't humanly maintain them. You also see that in that Muslim culture. Then look at the Netherlands. In what country could an electoral leader of such a large movement as mine be openly homosexual? How wonderful that that's possible. That's something that one can be proud of. And I'd like to keep it that way, thank you very much."

Fortuyn wrote a book called Against the Islamization of Our Culture in 1997.

Fortuynism: His Political Style

The political ideas and style of Pim Fortuyn and his LPF party are often called Fortuynism. Some people saw it as a protest against the supposed elitism and bureaucratic style of the Dutch government at the time. Others saw it as an appealing political style. This style was described as "openness, directness, and clearness," or simply as populism or charisma. Some believed Fortuynism was a unique set of ideas, with a different vision for society. Others argued it was a mix of liberalism, populism, and nationalism.

During the 2002 campaign, some accused Fortuyn of being "extreme right." However, he saw himself as neither a radical nationalist nor a defender of old, strict values. Instead, Fortuyn claimed he wanted to protect the socially liberal values of the Netherlands, like women's rights, from what he called "backward" Islamic culture. He held liberal views supporting same-sex marriage. Fortuyn also supported the state of Israel throughout his political career.

The LPF party also gained support from some ethnic minorities. One of Fortuyn's closest colleagues was of Cape Verdean origin, and one of the party's members of parliament was a young woman of Turkish descent.

His political ideas included:

- Civil liberties (individual freedoms)

- Classical liberalism (focus on individual rights and limited government)

- Criticism of Islam

- Deregulation (reducing government rules)

- Direct democracy (more direct public say in decisions)

- Euroscepticism (doubts about the European Union)

- Freedom of speech

- Laissez-faire (less government involvement in the economy)

- LGBT rights

- Republicanism (supporting a republic instead of a monarchy)

- Secularism (separation of religion and government)

- Separation of church and state

- Small government (less government spending and power)

- Women's rights

Fortuyn's Impact

Pim Fortuyn changed Dutch politics. The 2002 elections, held just weeks after his death, saw big losses for the liberal People's Party for Freedom and Democracy and especially the social democratic Labour Party. Both parties changed their leaders soon after. The winners were the Pim Fortuyn List and the Christian democratic Christian Democratic Appeal (CDA). The CDA leader, Jan Peter Balkenende, became Prime Minister.

Some people thought that Fortuyn's death made more people support the LPF. This led to the party's quick rise to 17% of the votes and 26 seats in parliament. Others believed that voters who would have supported the LPF instead voted for the CDA. This was because Balkenende had not attacked Fortuyn like other party leaders. Balkenende later said he agreed with some of Fortuyn's criticisms of multiculturalism.

Although the LPF formed a government with the Christian Democratic Appeal and the People's Party for Freedom and Democracy, it faced many internal problems. The government fell apart within three months due to conflicts within the LPF. In the next elections, the LPF won only eight seats and was not part of the new government. Many of the LPF's later leaders were not as charismatic as Fortuyn. As the next government continued many of the previous policies, it became harder for the LPF to offer a different vision. However, political experts thought that unhappy voters might still choose a non-traditional party if a good option appeared. Later, the right-wing Party for Freedom, which has strong views on immigration, won nine seats in the 2006 elections. It became the largest party in the 2023 elections, winning 37 seats.

The Netherlands has made its asylum policy stricter since Fortuyn's death. Some who disagreed with Fortuyn, like Paul Rosenmöller and Ad Melkert, felt that the political and social climate became harsher, especially towards immigrants and Muslims.

However, other commentators have since defended some of Fortuyn's ideas. Former Dutch Prime Minister Jan Peter Balkenende also stated that he later agreed with some of Fortuyn's criticisms of multiculturalism.

Dutch politics today is more divided than it used to be, especially on the issues Fortuyn was known for. People debate the success of their multicultural society. They also discuss whether newcomers need to integrate better. In 2004, the government decided to more strictly deport asylum seekers whose applications had been denied. This was a controversial decision. Fortuyn had supported a one-time pardon for asylum seekers who had lived in the Netherlands for a long time.

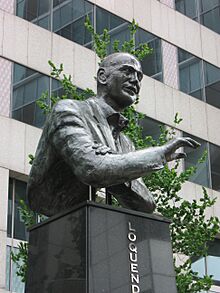

In 2004, in a TV show, Fortuyn was chosen as De Grootste Nederlander ("Greatest Dutchman of all-time"). He was followed closely by William of Orange, who led the war for Dutch independence. The voting was done by viewers through the internet and phone calls. The murder of Theo van Gogh by a Muslim a few days before likely influenced people's votes for Fortuyn. The show later revealed that William of Orange had received the most votes, but many could not be counted until after the official voting time due to technical problems. According to the official rules, the outcome was not changed.

Right-wing politicians gained more public influence after Fortuyn's death. Examples include Rita Verdonk, a former Minister for Integration & Immigration. Also, Geert Wilders, a strong critic of Islam and a Member of the House of Representatives, formed the Party for Freedom in 2006. This party became the second largest in the House of Representatives in 2017. Another is Thierry Baudet, leader of the Forum for Democracy party. These politicians often focus on the debate about cultural assimilation and integration.

Fortuyn's supporters created the annual Pim Fortuyn Prize. This award is given to people who best express Pim Fortuyn's ideas. Past winners include Ebru Umar and John van den Heuvel.

Selected Books by Pim Fortuyn

- Het zakenkabinet Fortuyn (1994)

- Beklemmend Nederland (1995)

- Uw baan staat op de tocht!: Het einde van de overlegeconomie (1995)

- Mijn collega komt zo bij u (1996)

- Tegen de islamisering van onze cultuur: Nederlandse identiteit als fundament (Against the Islamisation of Our Culture: Dutch Identity as Foundation) (1997)

- Zielloos Europa (Soulless Europe) (1997)

- 50 jaar Israel, hoe lang nog?: Tegen het tolereren van fundamentalisme (50 Years of Israel, How Much Longer?: Against Tolerating Fundamentalism) (1998)

- De derde revolutie (The Third Revolution) (1999)

- De verweesde samenleving (The Orphaned Society) (2002)

- De puinhopen van acht jaar Paars (The Rubble of Eight Purple Years) (2002)

|

See also

In Spanish: Pim Fortuyn para niños

In Spanish: Pim Fortuyn para niños

| Madam C. J. Walker |

| Janet Emerson Bashen |

| Annie Turnbo Malone |

| Maggie L. Walker |