Battle of the Netherlands facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of the Netherlands |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Western Front of World War II | |||||||

The centre of Rotterdam destroyed after bombing |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 9 divisions 700 guns 1 tank 5 tankettes 32 armored cars 145 aircraft Total: 280,000 men |

22 divisions 1,378 guns 759 tanks 830 aircraft Total: 750,000 men |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 2,332 KIA (Dutch Army) 8,000–9,000 wounded 216 French KIA 43 British KIA Over 2,000 civilians killed |

2,000–2,250 KIA 7,000–7,500 wounded 225–275 aircraft lost 1,350 prisoners to England |

||||||

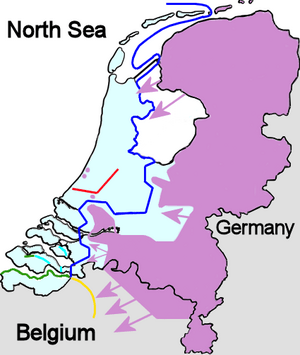

The Battle of the Netherlands was a quick fight during World War II. It happened when Germany invaded the Netherlands in May 1940. The battle lasted from May 10th to May 14th, 1940. Some Dutch troops in the province of Zeeland kept fighting until May 17th. After the battle, Germany took control of the entire country.

This battle was one of the first times that paratroopers were used in a big way. German soldiers jumped from planes to capture important places like airfields. This happened before their ground troops arrived.

The battle ended after the German air force, called the Luftwaffe, bombed the city of Rotterdam. Germany threatened to bomb other Dutch cities if the Dutch army did not give up. To save their cities from being destroyed, the Dutch surrendered. The Netherlands was then under German control until 1945.

Contents

Why Did Germany Invade the Netherlands?

The Start of World War II

Britain and France declared war on Germany in 1939. This happened after Germany invaded Poland. For a while, there were no big land battles in Western Europe. During this time, Britain and France prepared for war. Germany, meanwhile, took control of Poland.

In October 1939, Adolf Hitler ordered plans to invade the Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg. He wanted to use these countries as bases to attack Britain. He also wanted to stop the Allied forces from attacking Germany through this area.

Was the Netherlands Ready for War?

The Netherlands was not ready for an invasion. When Hitler came to power, the Dutch started to get their army ready, but very slowly. They only began to spend more money on defense in 1936.

Dutch leaders did not see Germany as a threat. They did not want to upset an important trading partner. The Dutch government also had strict budget limits because of the Great Depression.

Hendrikus Colijn, who was the Dutch Prime Minister from 1933 to 1939, did not think Germany would break Dutch neutrality. Neutrality means not taking sides in a war.

Growing Tensions in Europe

Things got more tense in Europe in the late 1930s. Germany took over the Rhineland in 1936. Then came the Anschluss (Germany taking over Austria) and the Sudeten crisis in 1938. Germany also took over Bohemia and Moravia in 1939. These events made the Dutch government more careful.

In April 1939, the Netherlands called up 100,000 men to be ready to fight. After Germany invaded Poland in September 1939, the Netherlands hoped to stay neutral. They had been neutral during World War I 25 years earlier.

The Dutch army was ready by August 1939. They spent a lot of money on defense. But it was hard to get new weapons during wartime. The Dutch had ordered some equipment from Germany, which caused delays.

Dutch Neutrality and Allied Plans

The Netherlands is located between France and Germany. This made it a good route for either side to attack the other. In January 1940, Winston Churchill tried to get the Dutch to join Britain. But both the Dutch and Belgians refused to join the Allies.

The Allies planned to attack Germany in 1941. The French thought about attacking the Low Countries if they did not join the Allies. If Germany attacked the Netherlands, the Allies would have to go through Belgium.

The Dutch government never fully decided what to do. Most leaders wanted to fight an attack. But a few did not want to become Germany's ally. The Dutch tried to arrange a peace between the Allies and Germany.

After Germany invaded Norway and Denmark, the Dutch military knew they might have to fight. They started to prepare for war. Dutch border troops were put on alert.

There were fears of German spies and traitors in the Netherlands. The Dutch prepared for attacks on airfields and ports. In April 1940, the Netherlands declared a state of emergency. But most people still hoped to avoid war.

How Strong Were the Dutch Forces?

The Dutch Army's Weaknesses

The Netherlands had good land for defense and some industries. But the Dutch army was very weak. Germany had much better equipment. The German army had tanks and dive bombers. The Dutch army had only 39 armored cars and five small tankettes. Their air force had old biplanes.

The Dutch military had not bought much new equipment since before World War I. In the 1920s, they spent very little on defense because of money problems. Only in 1936 did they create a special defense fund.

The Dutch army also lacked trained soldiers and professional leaders. There was just enough artillery for larger units. Light infantry units were spread out to slow down enemy movement.

They had about two thousand small forts called pillboxes. But these defense lines were thin. The Dutch did not have large, modern fortresses like Belgium.

The Dutch army had 48 infantry regiments and 22 border defense battalions. Belgium, in comparison, had many more divisions. After September 1939, the Dutch tried to improve their army, but with little success. Germany delayed weapon deliveries. France did not want to sell weapons to a neutral army.

The Dutch army had only two groups of armored cars. They had only five small Carden-Loyd Mark VI tankettes. Most of their artillery was old and pulled by horses. They had some modern guns, but not many.

Dutch infantry used old machine guns and rifles. The M.20 Lewis machine gun often jammed. The Dutch Mannlicher rifle was over 40 years old. The army also had few mortars, which made it hard for infantry to fight.

Even though the Netherlands had Philips, a large radio company, the Dutch army mostly used telephones. Only the artillery had many radio sets.

Worries About Air Attacks

After Germany used many airborne troops to attack Denmark and Norway in April 1940, the Dutch worried about a similar attack. To stop this, five infantry battalions were placed at main ports and airbases. These included airfields near The Hague and Rotterdam. They were given anti-aircraft guns, two tankettes, and twelve armored cars.

The Dutch Air Force

The Dutch air force had 155 aircraft. Many of these were older models. 74 of the 155 aircraft were biplanes. Only 125 of them were ready to fly. The Netherlands had aircraft companies like Fokker and Koolhoven. But the Dutch military could not afford new planes.

Training and Readiness

The Dutch Army was not only poorly equipped but also poorly trained. They had little experience leading large groups of soldiers. From 1932 to 1936, the Dutch Army did not do summer training exercises to save money.

Soldiers lacked many skills. Until 1938, new soldiers only served for 24 weeks, just enough for basic training. In 1938, service time increased to eleven months. There were not many professional military staff.

Most time was spent building defenses. There were not enough bullets for live fire training. In May 1940, the Dutch Army was not ready for battle. German generals and Hitler thought the Dutch military was weak. They expected to capture the Netherlands in about three to five days.

Dutch Defense Plans

The Water Line Defense

For centuries, the Netherlands used a defense system called the Dutch Water Line. This system could protect major cities by flooding parts of the countryside. In the 19th century, this line was moved east. It was called the New Holland Water Line.

This line was below sea level. It could be flooded with a few feet of water. This water was too shallow for boats but deep enough to turn the ground into mud. The area west of this line was called Fortress Holland. It was expected to hold out for a long time.

Some people thought these defenses could protect the country for three months without Allied help. Before the war, the plan was to move to this position. They hoped Germany would only pass through the southern provinces on its way to Belgium.

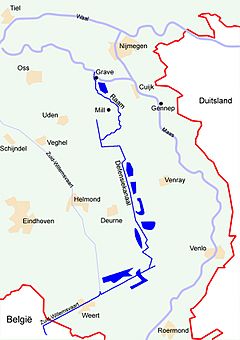

In 1939, a more eastern Main Defense Line (MDL) was built. This second defense line was extended south to the Belgian border. In the south, the goal was to slow down the Germans so the French could advance.

Where Were the Troops Placed?

In front of the Main Defense Line was the IJssel-Maaslinie. It had pillboxes and fourteen "border battalions." General Van Voorst tot Voorst wanted to use the rivers as a defense. He suggested fighting at river crossings near Arnhem and Gennep. This would make the Germans use a lot of energy before reaching the MDL.

The Dutch government thought this was too risky. They wanted the army to fight at the Grebbe Line and Peel-Raam Position, then fall back to Fortress Holland. General Reijnders, the commander, resigned because of these disagreements. General Henri Winkelman replaced him. Winkelman decided the Grebbe Line would be the main battleground in the north.

During the "Phoney War" (a period of little fighting), the Dutch said they were neutral. But secretly, the Dutch military talked with Belgium and France to plan a common defense. This failed because they disagreed on strategy.

Working with Belgium and France

Belgium, though neutral, had plans to work with Allied troops. This made it hard for the Dutch to make agreements with them. General Winkelman suggested that Belgium create a connecting line with the Peel-Raam Position. The Belgians refused unless the Dutch sent more troops to Limburg. The Dutch had no extra forces.

The Belgians decided to pull all their troops back to their main defense line, the Albert Canal. This left a 40-kilometer gap. The French were asked to fill it. The French Commander in Chief, General Maurice Gamelin, wanted to include the Dutch in his defense line. But he would not extend his supply lines unless the Belgians and Dutch joined the Allies. When both refused, Gamelin said he would occupy a position near Breda.

Winkelman decided on March 30th to give up the Peel-Raam Position if Germany attacked. He would move his Third Army Corps to the Linge river. This new position would have pillboxes.

German Plans and Forces

Hitler's Goals for the Netherlands

During the planning for Fall Gelb (the invasion of France and the Low Countries), the idea of leaving Fortress Holland alone was considered. But Hermann Göring, the head of the Luftwaffe, wanted to capture all of the Netherlands. He needed the Dutch airfields to use against Britain. He also worried the Allies might strengthen Fortress Holland and use the airfields to bomb German cities. A quick victory would also free up troops for other areas.

So, on January 17th, 1940, Germany decided to conquer all of the Netherlands. However, few units were available for this task. The main German attack would be in central Belgium and France. The attack on Fortress Holland was meant to be a distraction.

German Army Strength

The German 18th Army, led by General Georg von Küchler, was assigned to attack the Dutch. This was the weakest of the German armies in the battle. It had only four regular infantry divisions and three reserve divisions. Most of these units were new and had little fighting experience.

Like the Dutch army, most German soldiers (88%) lacked training. The German divisions were larger than the Dutch ones and had more firepower. But they still did not have enough men for a strong attack.

To add more men, the German 1st Cavalry Division was ordered to capture the weakly defended provinces east of the IJssel river. They also planned a landing in Holland near Enkhuizen using barges.

The Germans also used their new SS-Verfügungsdivision and Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler units. These elite units would attack the Dutch defenses.

To ensure victory, the Germans used new methods. They had trained two airborne divisions. The first, the 7. Flieger-Division, was made of paratroopers. The second, the 22nd Luftlande-Infanteriedivision, was airborne infantry.

These airborne troops would capture the airfields around The Hague. Their goal was to capture the Dutch government, the Dutch High Command, and Queen Wilhelmina.

If this first attack failed, the plan was to capture bridges at Rotterdam, Dordrecht, and Moerdijk. This would allow a mechanized force to move in. This force was the German 9th Panzer Division. It had 141 tanks. The plan was for them to break through the Dutch lines and join up with the airborne troops.

At the same time, another attack would be made against the Grebbe Line in the east. This was to push the Dutch army back to Fortress Holland. The Germans expected to capture Holland in a few days.

The Oster Affair: A Warning from Germany

Some German officers did not like the Nazi government. One of them was Colonel Hans Oster, a German intelligence officer. In March 1939, he started to give information to his friend, a Dutch military officer in Berlin, Major Gijsbertus J. Sas. This information included the German attack date.

Sas told the Allies. He even knew the date of the attack on Denmark and Norway. He also said a German armored division would try to attack the Netherlands and that there was a plan to capture the Queen. But the Dutch defense plan was not changed.

On May 4th, Sas warned that an attack was coming soon. On the evening of May 9th, Oster called his friend and said the attack would happen very soon. The Dutch troops were put on alert.

Oster was a leader of the German resistance against Hitler. He was later executed after a failed plot to kill Hitler in 1944.

The Battle Begins

May 10th: The Invasion Starts

On the morning of May 10th, 1940, Germany attacked the Netherlands, Belgium, France, and Luxembourg. During the night, the Luftwaffe flew into Dutch airspace. One group, Kampfgeschwader 4 (KG 4), attacked Dutch airfields. They destroyed 35 aircraft at De Kooy naval airfield. KG 4 also attacked Schiphol and The Hague airfields.

The Dutch lost many planes. By the end of the day, they had only 70 aircraft left. But they continued to fight the Luftwaffe, shooting down 13 German fighter planes by May 14th.

German paratroopers landed near the airfields. Dutch anti-aircraft guns shot down many German Ju 52 transport planes. Germany lost about 250 Ju 52 planes in the battle.

The attack on The Hague failed. The paratroopers did not capture the main airfield at Ypenburg in time for the airborne infantry to land. Dutch forces destroyed 18 German transport planes. The remaining planes landed in fields or on the beach, spreading out the troops.

None of the airfields could be used to land more troops. The paratroopers occupied Ypenburg but could not get into The Hague. Dutch troops blocked them. Dutch artillery also drove the Germans away from the other two airfields.

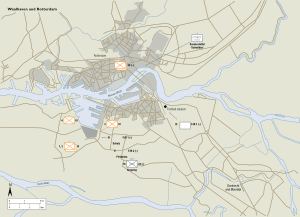

The attack on Rotterdam was more successful. Twelve Heinkel He 59 seaplanes landed in the city. They captured the Willemsbrug, a bridge over the Nieuwe Maas river. At the same time, the military airfield of Waalhaven was attacked by airborne forces.

A fight broke out, and the Dutch defenders were defeated. The Germans took control of IJsselmonde. The Royal Netherlands Navy tried to attack the Willemsbrug but was bombed.

The Germans also tried to capture bridges over the IJssel and Maas rivers. Most of these attempts failed, and the bridges were blown up by the Dutch. The only exception was the Gennep railway bridge. A German armored train crossed it, followed by a troop train. This allowed an infantry battalion to get behind the Dutch defense line.

Generally, German soldiers treated the Dutch people well at first. After the failed bridge assaults, German divisions began crossing the IJssel and Maas rivers. The first attacks were stopped by fire from Dutch pillboxes. But in most places, bombing destroyed the pillboxes, and German infantry crossed the rivers using pontoon bridges.

At Arnhem, the elite Leibstandarte Der Fuehrer led the attack and advanced to the Grebbe Line. A quick Dutch retreat was ordered.

Meanwhile, French troops with armored cars started to arrive at the Dutch border in the evening. The French 1st Mechanized Light Division moved forward.

In the north, the German 1st Cavalry Division reached Meppel and Groningen. They were slowed down by the Dutch blowing up 236 bridges. Dutch troops in that area were weak. In the south, six border battalions in Limburg slowed down the German Sixth Army. Maastricht surrendered before noon, but the Germans did not capture the main bridge intact.

May 11th: Dutch Counterattacks Fail

On May 11th, General Winkelman had two goals. First, he wanted to defeat the German airborne troops. He believed that the Germans holding the Moerdijk bridges would stop new Allied troops from arriving. Second, he wanted to help the French army build a strong defense line in North Brabant.

Little was achieved that day. The Dutch Light Division's attack against the airborne troops on IJsselmonde failed. The Germans defended the bridge over the Noord river, making it impossible for the Dutch to cross.

In Rotterdam, the Dutch failed to remove the German airborne troops from their bridge on the northern bank of the Maas. The two remaining Dutch bombers could not destroy the Willemsbrug. None of the attempts to defeat the German airborne forces were successful.

In North Brabant, the situation worsened. The French commanders expected four days to build a defense line near Breda. However, the best Dutch divisions had moved north, and the remaining forces were retreating. The Dutch Peel Division had to leave its trenches and artillery for an unprepared line. The Germans crossed the canal in several places. By the end of May 11th, the Peel Division had fallen apart. The French refused to advance further northeast than Tilburg.

Motorized units of SS Standarte "Der Fuehrer" reached the Grebbe Line on the evening of the 10th. On the morning of the 11th, German artillery bombed the Dutch outposts. Two German battalions attacked. The German bombing cut telephone lines, so the Dutch defenders could not call for artillery support.

By noon, the Germans broke through. By evening, they held all the outposts. The Dutch commander did not realize that elite SS troops were involved. He ordered a night attack, but heavy Dutch artillery fire stopped the German plans for a night attack.

In the North, the German 1st Cavalry Division advanced through Friesland. Most Dutch troops had already left the north.

May 12th: German Breakthroughs

On the morning of May 12th, General Winkelman still had hope. He thought a defense line could be set up in North Brabant with French help. He also expected the Dutch to defeat the German airborne forces. He was not aware of any danger to the Grebbe Line.

The German 9th Panzer Division crossed the Meuse river early on May 11th. It was slowed by roads full of infantry. The armored division was ordered to join the airborne troops once the Peel-Raam Position was captured.

The French 7th Army was ordered to pull back its left side because the German 6th Army was threatening it. The German 9th Panzer Division captured Colonel Schmidt, the Dutch commander in the province. The Dutch troops in the area lost all command. By noon, German armored cars had advanced 30 kilometers west, cutting off Fortress Holland from the main Allied force. By 4:45 PM, they reached the bridges.

At 1:35 PM, General Gamelin ordered all French troops in North Brabant to retreat to Antwerp.

The Dutch Light Division tried to recapture the Island of Dordrecht. But two of its battalions could not retake the suburbs. When the other two battalions approached the main road, they met German tanks. The battalions were bombed by German Stukas and fled. Dutch anti-tank guns stopped the German tanks. The Light Division then retreated.

In Rotterdam and around The Hague, little was done against the paratroopers. Most Dutch commanders did not attack.

In the east, the Germans attacked the Dutch defenders on the Grebbeberg. After artillery bombing, a battalion of Der Fuehrer attacked the main line. The Germans broke through. Dutch artillery did not fire on the enemy infantry.

Due to a lack of numbers, training, and heavy weapons, Dutch attacks failed against the well-trained SS troops. By evening, the Germans controlled the area. The Dutch main line was abandoned for over two miles to the north.

The Dutch knew that the forces on the Grebbe Line were not strong enough to stop all attacks alone. They were meant to delay an attack until new troops could be sent. Late in the evening, it was decided to attack from the north the next day.

In the North, the Wons position was weakly held. The first German unit to arrive broke through. This forced the Dutch defenders to retreat to the Enclosure Dike.

General Winkelman ordered the artillery in the Hoekse Waard to try to destroy the Moerdijk bridges. He also sent a team to Rotterdam to blow up the Willemsbrug. He ordered the oil reserves of Royal Dutch Shell at Pernis to be set on fire.

The Dutch government asked Winston Churchill for three British divisions. The new prime minister said he had no reserves. However, three British torpedo boats were sent to Lake IJssel.

The German command was very happy with the day's events. They decided to follow the French south towards Antwerp. Some forces would advance north with the 254th Infantry Division, most of the 9th Panzer Division, and SS Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler.

May 13th: The Queen Leaves and Rotterdam is Bombed

Early on May 13th, General Winkelman told the Dutch government there were serious problems. On land, the Dutch were cut off from the Allied front. No major Allied landings were planned by sea. Without support, there was no hope of successful resistance.

German tanks might quickly pass through Rotterdam. Winkelman had already ordered all anti-tank guns to be placed around The Hague to protect the government. However, the cabinet decided to continue fighting, giving the general the power to surrender the Army when he felt it was necessary.

Queen Wilhelmina was taken to safety. She left from Hoek van Holland on a British destroyer, HMS Hereward, and went to England. The previous evening, Princess Juliana, her husband, and their children had left from IJmuiden on HMS Codrington for Harwich.

Since the Queen was part of the government, the cabinet decided to follow her. The ministers sailed from Hoek van Holland on HMS Windsor to form a government in exile in London. Three Dutch merchant ships, escorted by British warships, took government gold and diamonds to the United Kingdom.

German tanks began crossing the Moerdijk bridge at 5:20 AM. The Dutch tried to block them. At 6:00 AM, the last Dutch medium bomber dropped two bombs on the bridge, but they did not explode. The bomber was shot down. Dutch artillery fire only slightly damaged the bridge. Attempts to flood the Island of Dordrecht failed.

The Light Division tried to advance west but met German tanks. They were bombed by Stukas and fled. Dutch anti-tank guns stopped the German tanks. The Light Division then retreated.

A German tank company tried to capture Dordrecht but retreated after heavy street fighting. At least two German tanks were destroyed. All Dutch troops left the island that night.

German armored forces advanced north into IJsselmonde island. Three tanks attacked the Barendrecht bridge but were destroyed by a single Dutch anti-tank gun. This area was later abandoned by Dutch troops.

In Rotterdam, a last attempt was made to blow up the Willemsbrug. Two Dutch companies attacked the bridge. They reached the bridge, and the 50 Germans almost surrendered. But heavy fire from the other side of the river stopped the attack.

In the North, the German 1st Cavalry Division commander, Major General Kurt Feldt, had to cross the Enclosure Dike. The main defenses had anti-tank guns and no cover for attackers. On May 13th, the position was reinforced. Several air attacks had little effect.

In the East, the Germans attacked the Grebbe Line. The German 366th Infantry Regiment was hit by Dutch artillery fire and had to retreat. This caused the German attack to fail.

On the south of the Grebbe Line, the Grebbeberg, the Germans used three SS battalions. On the morning of May 13th, a Dutch attack ran into a German attack. A fight followed, and the Dutch were defeated by the SS troops. The Dutch lost when the Grebbeberg area was bombed by 27 Ju 87 Stukas.

The German 207th Infantry Division was sent into battle at the Grebbeberg. The first German attackers were stopped with serious losses. A second attack managed to get past the trench line, which was then captured after heavy fighting.

The Germans expected the Dutch to fill any gaps in the line. But Dutch command had lost control. A wide gap appeared in the defenses. At 8:30 PM, the Dutch Army Corps were ordered to abandon the Grebbe Line and retreat.

May 14th: Rotterdam Bombed and Surrender

General Winkelman wanted to continue fighting for as long as possible to help the Allied war effort. In the North, a German artillery bombing of the Kornwerderzand Position began at 9:00 AM. But the German batteries were forced to move away by fire from a Dutch ship. Winkelman ordered the defense of an "Amsterdam Position," but only weak forces were available.

In the East, the field army retreated from the Grebbe Line. The new position had problems. The flooding was not ready, and earthworks had not been built.

On IJsselmonde, German forces prepared to cross the Maas in Rotterdam. The city was defended by about eight Dutch battalions. The main attack would be in the city center, with the German 9th Panzer Division advancing over the Willemsbrug. Then SS Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler would cross. East of Rotterdam, a German battalion would cross on boats.

The Germans decided to use air support. Kampfgeschwader 54, using Heinkel He 111 bombers, was moved to the Eighteenth Army.

German Generals Kurt Student and Schmidt wanted a limited air attack to stop the defenses. However, Luftwaffe commander Hermann Göring, worried about his surrounded airborne troops, wanted a total bombing of Rotterdam.

At 9:00 AM, a German messenger crossed the Willemsbrug to deliver a message to Colonel Pieter Scharroo, the Dutch commander of Rotterdam. It demanded the surrender of the city. If an answer was not received within two hours, severe destruction would follow.

Scharroo did not receive the message until 10:30 AM. He did not want to surrender. He received a new message requiring an answer by 4:20 PM. At 1:20 PM, two groups of Heinkels arrived.

Schmidt ordered red flares to be fired to stop the bombing. But only the squadron from the southwest stopped its attack after dropping their first three bombs. The other 54 Heinkels dropped 1308 bombs, destroying the inner city and killing 814 civilians. The fires destroyed about 24,000 houses, making almost 80,000 people homeless.

At 3:50 PM, Scharroo surrendered to Schmidt in person. Göring had ordered a second bombing unless all of Rotterdam was occupied. Schmidt sent a message claiming the city was taken, which was not true. The bombers were called back just in time.

The Surrender of the Dutch Army

General Winkelman at first wanted to continue the fight. Bombings were not seen as a reason to surrender. The Hague could still fight off an armored attack.

He received a message that the Germans demanded the surrender of Utrecht. Planes dropped messages saying that only surrender would stop the city from being destroyed. Winkelman believed the Germans would bomb any city that resisted. Since he was told to avoid suffering and the Dutch military was weak, he decided to surrender.

All army units were informed at 4:50 PM of his decision. They were ordered to destroy their weapons and surrender to the nearest German units. At 5:20 PM, the German envoy in The Hague was informed. Around 7:00 PM, Winkelman gave a radio speech informing the Dutch people. This is how the German command learned the Dutch had surrendered.

On the morning of May 14th, the commander of the Royal Dutch Navy, Vice-Admiral Johannes Furstner, left the country to continue the fight. Dutch naval vessels were generally not included in the surrender. Eight ships had already left, some smaller vessels were sunk, and nine others sailed for England that evening. The Hr. Ms. Johan Maurits van Nassau was sunk by German bombers while crossing.

The commander of the main Dutch naval port of Den Helder, Rear-Admiral Hoyte Jolles, wanted his base to continue fighting. Winkelman had to convince him to obey the surrender order. Large parts of the Dutch Army did not want to accept the surrender.

At 5:00 AM on May 15th, a German messenger reached The Hague. He invited Winkelman to Rijsoord for a meeting with von Küchler to sign a written surrender. Winkelman surrendered the army, naval, and air forces. The document was signed at 10:15 AM.

Fighting in Zeeland

The province of Zeeland was not part of the surrender. Fighting continued there alongside French troops. The Dutch forces in Zeeland had eight battalions of army and naval troops. They were commanded by Rear-Admiral Hendrik Jan van der Stad. The area was under naval command because of the naval port of Flushing.

The defense of Zeeuws-Vlaanderen, the Dutch part of Flanders, was left to the Allies. The main Dutch army forces were in Zuid-Beveland east of Walcheren. They tried to block this route to Flushing.

Zuid-Beveland was connected to the coast of North Brabant. At its eastern end, the Bath Position was defended by an infantry battalion. At its western end was the Zanddijk Position, held by three battalions.

From May 11th, the area was reinforced by two French infantry divisions. On May 13th, the Dutch troops were placed under French command. There were poor communications and disagreements between the Dutch and French. The Dutch thought the Bath and Zanddijk Positions could be defended because of flooding. But the French commander, General Pierre-Servais Durand, wanted his troops hidden behind obstacles.

On the evening of May 13th, a French regiment occupied the Canal through Zuid-Beveland. The Allied forces were not grouped together enough. This allowed the Germans to defeat them even though they had fewer men.

On May 14th, the Germans had occupied almost all of North Brabant. SS-Standarte Deutschland reached the Bath Position. This cut off the retreat of a French unit, which was destroyed defending Bergen-op-Zoom. The morale of the defenders at the Bath Position weakened when they heard Winkelman had surrendered. Many decided it was useless for Zeeland to keep fighting.

An artillery bombing on the position that evening caused the commanding officers to leave. Then the troops left.

On the morning of May 15th, SS-Standarte Deutschland approached the Zanddijk Position. A first attack was stopped. But the bombing caused the battalions in the main positions to flee, and the entire line was abandoned around 2:00 PM.

On May 16th, SS-Standarte Deutschland approached the Canal through Zuid-Beveland. The French regiment was partly dug in and helped by three Dutch battalions. An air bombing happened that morning. The first German crossings led to a complete collapse of the defense. On May 16th, the island of Tholen was captured. On May 17th, Schouwen-Duiveland was captured.

The commanders of the Dutch troops on South-Beveland refused orders to attack the Germans. On May 17th, a night attack failed. The Germans then demanded the surrender of the island. When this was refused, they bombed Arnemuiden and Flushing. Middelburg, the province's capital, was shelled by artillery, and its inner city partly burned down.

The heavy bombing made the French defenders lose hope. The Germans managed to capture a bridge around noon. The few Dutch troops on Walcheren stopped fighting. That evening, the Germans threatened to attack the French forces in Flushing. But most troops were evacuated over the Western Scheldt.

After North-Beveland surrendered on May 18th, Zeeuws-Vlaanderen was the last unoccupied Dutch territory. On orders from the French, all Dutch troops were withdrawn on May 19th to Ostend in Belgium. By May 27th, all of Zeeuws-Vlaanderen had been occupied.

What Happened After the Battle?

After the Dutch defeat, Queen Wilhelmina set up a government-in-exile in England. The German occupation began on May 17th, 1940. It would be five years before the entire country was freed. Over 210,000 Dutch people died during the war. This included 104,000 Jews and other minorities who were killed because of their background. Another 70,000 Dutch people died from poor food or limited medical care.

Images for kids

-

General der Fallschirmjäger Kurt Student

See also

In Spanish: Batalla de los Países Bajos para niños

In Spanish: Batalla de los Países Bajos para niños