History of Luxembourg facts for kids

The history of Luxembourg tells the story of this small country and its land. Even though people lived here in Roman times, Luxembourg's own history really started in 963.

For the next 500 years, the strong House of Luxembourg became very important. But when this family line ended, Luxembourg lost its independence for a while. After being ruled by Burgundy, it became part of the Habsburg family's lands in 1477.

Later, after a big war, Luxembourg became part of the Southern Netherlands. In 1713, it went to the Austrian branch of the Habsburg family. After being taken over by Revolutionary France, a meeting called the Vienna Congress in 1815 made Luxembourg a Grand Duchy. This meant it was ruled by the same king as the Netherlands, but it was still a separate state.

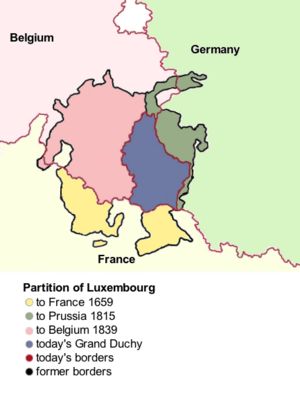

This treaty also split Luxembourg's land for the second time. The first split was in 1658, and a third happened in 1839. These splits made Luxembourg smaller. However, the 1839 treaty officially made Luxembourg an independent country. This independence was confirmed after a big disagreement called the Luxembourg Crisis in 1867.

In the years that followed, Germany became more influential in Luxembourg, especially after a different royal family took over in 1890. Germany occupied Luxembourg during World War I (1914-1918) and again during World War II (1940-1944). Since the end of World War II, Luxembourg has become one of the richest countries in the world. This is thanks to its stable government and its strong involvement in European integration.

Contents

Early History: From Stone Age to Roman Times

| History of the Low Countries | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frisii | Belgae | |||||||

| Cana- nefates |

Chamavi, Tubantes |

Gallia Belgica (55 BC – 5th c. AD) Germania Inferior (83 – 5th c.) |

||||||

| Salian Franks | Batavi | |||||||

| unpopulated (4th–5th c.) |

Saxons | Salian Franks (4th–5th c.) |

||||||

| Frisian Kingdom (6th c.–734) |

Frankish Kingdom (481–843)—Carolingian Empire (800–843) | |||||||

| Austrasia (511–687) | ||||||||

| Middle Francia (843–855) | West Francia (843–) |

|||||||

| Kingdom of Lotharingia (855– 959) Duchy of Lower Lorraine (959–) |

||||||||

| Frisia | ||||||||

Frisian Freedom (11–16th century) |

County of Holland (880–1432) |

Bishopric of Utrecht (695–1456) |

Duchy of Brabant (1183–1430) Duchy of Guelders (1046–1543) |

County of Flanders (862–1384) |

County of Hainaut (1071–1432) County of Namur (981–1421) |

P.-Bish. of Liège (980–1794) |

Duchy of Luxem- bourg (1059–1443) |

|

Burgundian Netherlands (1384–1482) |

||||||||

Habsburg Netherlands (1482–1795) (Seventeen Provinces after 1543) |

||||||||

Dutch Republic (1581–1795) |

Spanish Netherlands (1556–1714) |

|||||||

Austrian Netherlands (1714–1795) |

||||||||

United States of Belgium (1790) |

R. Liège (1789–'91) |

|||||||

Batavian Republic (1795–1806) Kingdom of Holland (1806–1810) |

associated with French First Republic (1795–1804) part of First French Empire (1804–1815) |

|||||||

Princip. of the Netherlands (1813–1815) |

||||||||

| United Kingdom of the Netherlands (1815–1830) | Gr D. L. (1815–) |

|||||||

Kingdom of the Netherlands (1839–) |

Kingdom of Belgium (1830–) |

|||||||

| Gr D. of Luxem- bourg (1890–) |

||||||||

Evidence shows that people lived in the area of modern Luxembourg over 35,000 years ago. These early people lived during the Old Stone Age. The oldest items found are decorated bones from Oetrange.

The first real signs of settled life come from the New Stone Age, around 5,000 BC. We have found traces of houses from this time. These houses were made from tree trunks, mud-covered wicker walls, and roofs of reeds or straw. Pottery from this period has been found near Remerschen.

Later, in the Bronze Age (from about 13th to 8th century BC), there is more proof of people living here. Sites like Nospelt and Dalheim show evidence of homes and items like pottery, knives, and jewelry.

The Celts and Romans in Luxembourg

During the Iron Age (from about 600 BC to 100 AD), the area of present-day Luxembourg was home to the Celts. A Gaulish tribe called the Treveri lived here. They were very successful in the 1st century BC. The Treveri built strong, fortified settlements called oppida near the Moselle valley. Many archaeological finds from this time come from tombs, especially near Titelberg. This large site tells us a lot about their homes and crafts.

The Romans, led by Julius Caesar, took control of the area in 53 BC. Julius Caesar mentioned the land of modern Luxembourg in his writings. The Treveri tribe worked well with the Romans and quickly adopted Roman ways of life. Even two small revolts in the 1st century AD did not ruin their good relationship with Rome.

The land of the Treveri first belonged to a Roman province called Gallia Celtica. Later, around 90 AD, it became part of Gallia Belgica.

From the 4th century, Germanic Franks started moving into Gallia Belgica. Rome left the area in 406 AD. By the 480s, the land that would become Luxembourg was part of the Merovingian kingdom of Austrasia. This kingdom later became a central part of the Carolingian Empire.

After the Treaty of Verdun in 843, the land went to Middle Francia. In 855, it became part of Lotharingia. When Lotharingia was divided in 959, it then joined the Duchy of Upper Lorraine within the Holy Roman Empire.

The Beginning of Luxembourg: County and Duchy

The true history of Luxembourg began with the building of Luxembourg Castle in 963. Siegfried I, count of Ardennes traded some of his family lands with monks from the Abbey of St. Maximin in Trier. In return, he received an old fort called Lucilinburhuc, which means "little castle." Some historians believe the name comes from Letze, meaning fortification. This might have been an old Roman watchtower or an early medieval refuge.

Over time, a town grew around the Luxembourg fort. This town became the center of a small but important state. Its location was very strategic for France, Germany, and the Netherlands. The fortress, built on a rocky hill called the Bock, was made stronger and larger by many rulers over the years. These rulers included the Bourbons, Habsburgs, and Hohenzollerns. They made it one of the strongest fortresses in Europe, earning it the nickname ‘Gibraltar of the North’.

Habsburg and French Rule (1477–1815)

From the 17th to 18th centuries, rulers from Brandenburg (later kings of Prussia) claimed Luxembourg. They believed they were the rightful heirs. This claim eventually led to some parts of Luxembourg joining Prussia in 1813.

In 1598, Philip II of Spain gave Luxembourg and other Low Countries to his daughter, Isabella Clara Eugenia, and her husband, Albert VII, Archduke of Austria. After Albert died without children in 1621, Luxembourg went to his great-nephew, Philip IV of Spain.

How Luxembourg Was Governed

In the early 1600s, Luxembourg was controlled by Spain. It was managed from Brussels by a person chosen by the Spanish King, usually called the Governor-General.

The Governor-General had a representative in Luxembourg called the Governor. This Governor worked with a group of advisors called the Provincial Council. This council acted as the government of Luxembourg. It also served as the main court of justice.

Luxembourg was divided into different types of areas:

- Seigneuries (lordships), owned by noble families.

- Important abbeys, whose lands were used by abbots.

- Prévôtés, directly managed by the King's officials.

- Towns, which had their own laws.

From the 14th century, the people were represented by an assembly called the Estates. This group included:

- Noble families

- Leaders of the largest abbeys (like St. Maximin's Abbey and Echternach Abbey)

- Representatives from certain towns, such as Luxembourg, Echternach, and Diekirch. Villages did not have representatives.

French Invasions and Changes

Luxembourg was invaded by Louis XIV of France in 1684. This worried other European countries and led to the formation of the League of Augsburg. In the war that followed, France had to give Luxembourg back to the Habsburgs in 1697.

During this time of French rule, the famous engineer Vauban made the fortress defenses much stronger.

Habsburg rule was confirmed again in 1715 by the Treaty of Utrecht. Luxembourg became part of the Southern Netherlands. Austrian rulers sometimes thought about trading Luxembourg for other lands closer to their main power center in Vienna. However, these plans never became permanent.

During the War of the First Coalition, Revolutionary France conquered and took over Luxembourg. In 1795, it became part of a French region called the Forêts. This takeover was made official in 1797. In 1798, Luxembourgish farmers started a rebellion against the French, but it was quickly stopped. This short rebellion is known as the Peasant's War.

Becoming Independent (1815–1890)

Luxembourg remained under French rule until Napoleon's defeat in 1815. After the French left, the Allies set up a temporary government.

The Congress of Vienna in 1815 officially gave Luxembourg its own independence. Prussia had already taken some land from Luxembourg in 1813. France also had a strong claim to Luxembourg. However, the Austrian Emperor's advisor was not keen on getting Luxembourg back because it was too far from Austria.

Prussia and the Netherlands, both wanting Luxembourg, made a deal. Prussia received some land in Central Germany, and the Prince of Orange (who ruled the Netherlands) received Luxembourg. In 1815, Luxembourg joined the German Confederation. In 1842, it also joined the German Customs Union, which helped trade.

Luxembourg, though a bit smaller than its medieval size, gained importance by becoming a grand duchy. It was placed under the rule of William I of the Netherlands. This was the first time Luxembourg had a ruler who was not from its old royal family. However, Luxembourg's military importance to Prussia meant it could not become a full part of the Dutch kingdom. The fortress was guarded by Prussian soldiers. Luxembourg became a member of the German Confederation, with Prussia in charge of its defense, while also being under the rule of the Netherlands.

In July 1819, a visitor from Britain, Norwich Duff, described Luxembourg City as "one of the strongest fortifications in Europe." He noted that it was in Holland (meaning the Netherlands) but had 5,000 Prussian troops guarding it. The civil government and taxes were managed by the Dutch. He found the town clean with good houses.

In 1820, Luxembourg made the metric system of measurement compulsory. Before this, they used local units like the "malter."

Many Luxembourgers joined the Belgian revolution against Dutch rule. From 1830 to 1839, most of Luxembourg was considered a province of the new Belgian state. Only the fortress and its immediate area remained under Dutch control. The Treaty of London in 1839 made the Grand Duchy fully sovereign and independent. It was still ruled by the King of the Netherlands, but as a separate state. In return, the larger western part of the duchy, where French was spoken, was given to Belgium.

This loss of land made the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg mostly German-speaking, though French culture remained strong. Losing the Belgian markets also caused economic problems. To help, the Grand Duke joined Luxembourg with the German Zollverein (Customs Union) in 1842. Still, Luxembourg remained a farming country for most of the century. Because of this, about one in five Luxembourgers moved to the United States between 1841 and 1891.

From the 1830s, Luxembourg began to develop its own national identity. The Catholic Church helped create a unique cultural feeling. By 1840, Luxembourg had its own diocese, and in 1870, a separate bishopric. The Luxemburger Wort, which became the main national newspaper, was also closely linked to the church. Language also helped build Luxembourgish identity. While people spoke two languages, Luxembourgish became used in local books and newspapers, especially for local topics and folklore. French was used for diplomacy and international matters.

The Crisis of 1867

In 1867, Luxembourg's independence was confirmed after a difficult period. There was even some unrest because of plans to join Luxembourg with Belgium, Germany, or France. The crisis of 1867 almost led to war between France and Prussia. This was over Luxembourg's status, as it had become free of German control when the German Confederation ended in 1866.

William III, King of the Netherlands and ruler of Luxembourg, wanted to sell the grand duchy to France's Emperor Napoleon III. But he changed his mind when Prussian chancellor, Otto von Bismarck, disagreed. The rising tension led to a conference in London in 1867. Britain acted as a mediator. Bismarck influenced public opinion, stopping the sale to France. The problem was solved by the second Treaty of London. This treaty guaranteed Luxembourg's lasting independence and neutrality. The fortress walls were taken down, and the Prussian soldiers left.

Famous visitors to Luxembourg in the 18th and 19th centuries included the German poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, the French writers Émile Zola and Victor Hugo, the Hungarian composer Franz Liszt, and the English painter Joseph Mallord William Turner.

Separation and the World Wars (1890–1945)

Luxembourg remained under the rule of the Kings of the Netherlands until William III died in 1890. Since William III had only a daughter, Wilhelmina, the crown of the Netherlands passed to her. However, due to an old family agreement from 1783, the crown of Luxembourg could only pass to a male heir if there were any. So, Luxembourg went to a different branch of the Nassau family: Adolphe, who became the Grand Duke of Luxembourg.

By the early 1900s, Luxembourg started to develop its own national identity, moving away from German cultural ties. Writers like Nicolas Ries helped make Luxembourgish a literary language. Nationalist groups also formed, showing anti-German and anti-French feelings. In 1912, the Education Law of 1912 made Luxembourgish an official and required school subject. More people started moving into Luxembourg than leaving. Luxembourg's politics settled into three main parties: socialists, liberals, and conservatives.

Luxembourg in World War I

Luxembourg's neutrality, agreed upon in the 1867 Treaty of London, was broken in 1914. German troops occupied Luxembourg. However, the government was allowed to stay in place, and Luxembourg was not officially made part of Germany. While the government officially stayed neutral, the people supported the Allied forces. Many Luxembourgers even joined the French army.

The government's neutrality during the occupation caused disagreements. The German occupation led to strong anti-German feelings. The monarchy was accused of working with Germany, which led to calls for its removal. As a result, Marie-Adélaïde, Grand Duchess of Luxembourg stepped down. Her sister, Charlotte, became Grand Duchess. Soon after, in 1919, a vote was held. The public voted to keep the monarchy. The war also led to social changes and the creation of the first trades union in Luxembourg.

Between the World Wars

When the German occupation ended in November 1918, there was much uncertainty. The winning Allied countries were unhappy with the choices made by Luxembourg's leaders. Some Belgian politicians even wanted Luxembourg to become part of a larger Belgium. Inside Luxembourg, a strong group wanted to create a republic. In the end, the Grand Duchy remained a monarchy, but with a new head of state, Charlotte. In 1921, Luxembourg formed an economic and money union with Belgium. However, Germany remained its most important trading partner for most of the 20th century.

The introduction of universal suffrage (the right to vote for all men and women) helped the conservative Party of the Right. This party played the main role in government throughout the 20th century. Their success was partly due to the support of the church, as over 90 percent of the population was Catholic.

Internationally, Luxembourg tried to become more visible between the wars. Especially under Joseph Bech, the head of foreign affairs, the country became more active in international groups. This was to ensure its independence. On December 16, 1920, Luxembourg joined the League of Nations. Economically, in the 1920s and 1930s, farming became less important, while industry and especially the service sector grew.

In the 1930s, the situation inside Luxembourg became difficult. Luxembourgish politics were influenced by European left- and right-wing ideas. The government tried to stop unrest led by communists in industrial areas. It also continued friendly policies towards Nazi Germany, which led to much criticism. An attempt to outlaw the Communist Party, known as the Maulkuerfgesetz (the "muzzle" law), was rejected by a public vote in 1937.

Luxembourg in World War II

When Second World War started in September 1939, Luxembourg declared its neutrality. But on May 10, 1940, German armed forces invaded. They met little resistance, as most of Luxembourg's small volunteer army stayed in their barracks. The capital city was occupied before noon. The Luxembourgish government and royal family had to flee into exile.

The Luxembourg royal family received visas and traveled to the United States. During the war, Grand Duchess Charlotte broadcast messages via the BBC to give hope to her people.

Luxembourg remained under German military occupation until August 1942. Then, Nazi Germany officially took it over as part of a German region. The German authorities declared Luxembourgers to be German citizens. They forced 13,000 Luxembourgers to join the German army. Sadly, 2,848 Luxembourgers died fighting in the German army.

About 3,500 Jewish people lived in Luxembourg before the war. An estimated 1,000 to 2,500 were killed in the Holocaust.

Luxembourgish people resisted the German takeover in many ways. At first, it was passive resistance, like the Spéngelskrich (meaning "War of the Pins"), and refusing to speak German. Since French was forbidden, many Luxembourgers started using old Luxembourgish words again, which led to a rebirth of the language. The Germans responded to opposition with deportation, forced labour, forced conscription, and even sending people to Nazi concentration camps or executing them.

In October 1941, a census asked people about their citizenship, mother tongue, and ethnicity. Most people answered "Lëtzebuergesch" (Luxembourgish). This showed their opposition to being taken over by Nazi Germany. This act of rebellion is called dräimol Lëtzebuergesch (‘three times Luxembourgish’). When Germans started forcing Luxembourgers into their army in 1942, it led to many strikes. This event is known as the Generalstreik.

Executions happened after the general strike from September 1 to 3, 1942. This strike stopped administration, farming, industry, and education in response to the forced conscription. The Germans violently stopped the strike. They executed 21 strikers and sent hundreds more to concentration camps. The general strike in Luxembourg was one of the few mass strikes against the German war machine in Western Europe.

U.S. forces freed most of Luxembourg in September 1944. They entered the capital city on September 10, 1944. During the Ardennes Offensive (also known as the Battle of the Bulge), German troops took back most of northern Luxembourg for a few weeks. Allied forces finally drove out the Germans in January 1945.

Between December 1944 and February 1945, the recently freed city of Luxembourg was targeted by German V-3 long-range guns. These guns fired 183 rounds at Luxembourg. While not very accurate, 44 rounds hit the city, killing 10 people and wounding 35. The bombardments stopped when the American Army got close to the German gun positions in February 1945.

In total, out of a pre-war population of 293,000, 5,259 Luxembourgers died during the war.

Modern History (Since 1945)

After World War II, Luxembourg changed its policy of neutrality. It became a founding member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and the United Nations. It also signed the Treaty of Rome and formed a money union with Belgium in 1948. Later, it formed an economic union with Belgium and the Netherlands, known as BeNeLux.

From 1945 to 2005, Luxembourg's economy changed a lot. The steel industry faced a crisis from the mid-1970s to the late 1980s. This almost caused a recession because the steel industry was so dominant. However, a special committee with government, business, and union leaders worked together. They prevented major social unrest, creating the idea of a "Luxembourg model" known for social peace.

In the early 21st century, Luxembourg had one of the highest incomes per person in the world. This was mainly due to its strong financial sector, which grew important in the late 1960s. Thirty-five years later, one-third of the country's tax money came from this sector.

Luxembourg has been a strong supporter of the European Union, following the ideas of Robert Schuman. It was one of the six founding members of the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) in 1952 and the European Economic Community (EEC) (which later became the European Union) in 1957. In 1999, it joined the euro currency area.

Because of its contacts with the Dutch and Belgian governments during the war, Luxembourg actively joined international organizations. During the Cold War, Luxembourg clearly sided with the West, joining NATO in 1949. Its involvement in rebuilding Europe was rarely questioned by politicians or the public.

Despite its small size, Luxembourg often played a role as a mediator between larger countries. This role, especially between Germany and France, was seen as a key part of its national identity. It allowed Luxembourgers not to have to choose between their two big neighbors. The country also hosts many European institutions, like the European Court of Justice.

Luxembourg's small size no longer seemed to threaten its existence. The creation of the Banque Centrale du Luxembourg (Central Bank of Luxembourg) in 1998 and the University of Luxembourg in 2003 showed a continued desire to be a "real" nation. The decision in 1985 to declare Lëtzebuergesch (Luxembourgish) the national language was also a step in confirming the country's independence. In fact, Luxembourg has three main languages: Lëtzebuergesch is the spoken language, German is the written language most Luxembourgers are fluent in, and French is used for official letters and law.

In 1985, the country experienced a mysterious bombing spree. These attacks mostly targeted electrical masts and other installations.

In 1995, Luxembourg provided the president of the European Commission, former Prime Minister Jacques Santer. He later had to resign in March 1999 due to accusations against other commission members.

Prime Minister Jean-Claude Juncker continued this European tradition. On September 10, 2004, Juncker became the president of the group of finance ministers from the 12 countries that use the euro. This role earned him the nickname "Mr Euro."

The current ruler is Grand Duke Henri. Henri's father, Jean, became Grand Duke in 1964. Jean's oldest son, Prince Henri, was named "Lieutenant Représentant" (Hereditary Grand Duke) in 1998. On December 24, 1999, Prime Minister Juncker announced that Grand Duke Jean would step down on October 7, 2000. Prince Henri then took over as Grand Duke.

On July 10, 2005, after threats of resignation by Prime Minister Juncker, the proposed European Constitution was approved by 56.52% of voters.

In July 2013, Prime Minister Jean-Claude Juncker announced he would resign after a secret service scandal. He had been prime minister since 1995.

In December 2013, Xavier Bettel became the new prime minister, succeeding Juncker. Bettel's Democratic Party (DP) formed a coalition with Liberals, Social Democrats, and Greens. They won a majority of 32 out of 60 seats in the 2013 election. However, Juncker's party remained the largest with 23 seats.

In July 2014, the European Parliament elected former Luxembourg prime minister Jean-Claude Juncker as the President of the European Commission. He took office on November 1, 2014.

In December 2018, Prime Minister Xavier Bettel was sworn in for a second term. His liberal-led coalition had won a close victory in the 2018 election. In February 2020, his government made free public transport available across Luxembourg. This made Luxembourg the first country in the world to do this nationwide.

In October 2023, the Christian Social People's Party (CSV) won the general election. This meant Prime Minister Xavier Bettel's ruling coalition lost its clear majority. In November 2023, Luc Frieden, the leader of CSV, became the new Prime minister of Luxembourg. He formed a coalition with the liberal Democratic Party (DP). This meant outgoing Prime Minister Xavier Bettel remained in government as foreign minister and deputy prime minister.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Luxemburgo para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Luxemburgo para niños

- List of monarchs of Luxembourg

- List of prime ministers of Luxembourg

- Politics of Luxembourg

- History of rail transport in Luxembourg, 1846 to present day

General:

Images for kids