History of French facts for kids

French is a "Romance language," which means it comes mostly from Vulgar Latin, the everyday language spoken by the ancient Romans. It belongs to a group called Gallo-Romance languages.

The story of a language is often split into two parts: "external history" looks at how things like people, politics, society, and technology changed the language. "Internal history" looks at how the sounds and grammar of the language itself changed over time.

Contents

How French Changed: People and Politics

Roman Gaul: Where France Began

Before the Romans took over what is now France (around 58–52 BC), many people living there spoke Celtic languages. The Romans called these people Gauls and Belgae. In southern France, there were also other groups, like the Iberians near the Pyrenees, the Ligures near the Alps, Greek settlers in cities like Marseille, and Basques in the southwest.

Even after the Romans arrived, the Gauls kept speaking their language, Gaulish, for centuries. Latin and Gaulish lived side-by-side. The last known mention of Gaulish was in the late 500s AD.

The French language grew from Vulgar Latin, but Gaulish had an impact on it. For example, some French words come from Gaulish, especially words about nature and farm life. About 200 French words have Gaulish roots.

Here are some examples of words from Gaulish:

- Land features: bief (mill race), combe (hollow), lande (heath).

- Plant names: bouleau (birch), chêne (oak), if (yew).

- Wildlife: alouette (lark), pinson (finch).

- Farm life: boue (mud), charrue (plow), mouton (sheep), tonne (barrel).

- Common verbs: braire (to bray), changer (to change), craindre (to fear).

- Loan translations: aveugle (blind), which is like the Gaulish word for "eyeless."

Latin quickly became popular among city leaders for business and education. But it took much longer, about four or five centuries, for Latin to spread to the countryside. This happened as power shifted from cities to villages, and more people became tied to the land.

The Franks and Their Influence

Around the 3rd century, Germanic tribes from the north and east started moving into Gaul. The most important groups for the French language were the Franks in northern France. Other groups included the Alemanni near the German border, the Burgundians in the Rhône Valley, and the Visigoths in the Aquitaine region.

The Frankish language greatly changed the Latin spoken in these areas. It affected how words were pronounced and how sentences were put together. It also brought many new words into the language. Some experts say that about 15% of modern French words come from Germanic languages, including Frankish.

Here are some ways Frankish influenced French:

- The name of the language itself, français, comes from the Germanic word frankisc, meaning "French" or "Frankish."

- Many terms related to social structure, like baron, bâtard (bastard), and maréchal (marshal).

- Military terms: guerre (war), garder (to guard), flèche (arrow).

- Colors: blanc (white), bleu (blue), blond (blond), gris (grey).

- Other common words: abandonner (to abandon), danser (to dance), jardin (garden), laid (ugly), riche (rich), soupe (soup), tomber (to fall).

- Word endings like -ard (e.g., canard - duck) and -aud (e.g., crapaud - toad).

- Many verbs ending in -ir, like choisir (to choose) and guérir (to heal).

- Prefixes like mé(s)- (e.g., mésentente - misunderstanding) and for- (e.g., forcené - frantic).

- French uses a subject pronoun before the verb (e.g., je vois - I see), similar to Germanic languages, while many other Romance languages don't always need it.

- Asking a question by flipping the subject and verb (e.g., Avez-vous un crayon? - Do you have a pencil?) is also like Germanic languages.

- Adjectives often come before the noun (e.g., belle femme - beautiful woman), which is more common in French than in other Romance languages. Sometimes, the order changes the meaning, like grand homme (great man) versus homme grand (tall man).

Frankish had a huge impact on the birth of Old French. This is why Old French is one of the earliest Romance languages to be written down, seen in texts like the Oaths of Strasbourg (842 AD). The new way of speaking became so different from Latin that people couldn't understand each other anymore.

The influence of Frankish also helps explain the differences between the langue d'oïl (spoken in northern France) and langue d'oc (spoken in southern France). Northern France remained bilingual (speaking two languages) in Latin and Germanic for several centuries, which shaped the Latin spoken there and made it unique.

Normans and Words from the Low Countries

In 1204 AD, the Duchy of Normandy became part of France. This brought many words into French from the Norman language, which had Scandinavian roots. About 150 words of Scandinavian origin are still used today, mostly about the sea and sailing, like flotte (fleet), vague (wave), and quille (keel). Others are about farming and daily life, like accroupir (to crouch) and haras (stud farm).

Many words borrowed from Dutch also relate to trade or the sea, such as boulevard (boulevard), fret (freight), and matelot (sailor). Similarly, words from Low German (like homard - lobster) and English from this period (like bateau - boat, and yacht - yacht) also entered French.

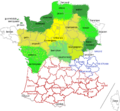

The Langue d'oïl and Langue d'oc

The medieval Italian poet Dante once grouped Romance languages by how they said "yes."

- Northern France used oïl (from Latin hoc ille, meaning "that is it"). These are the langue d'oïl languages.

- Southern France used oc (from Latin hoc, meaning "that"). These are the langue d'oc languages.

- Italy and the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal) used si (from Latin sic, meaning "thus").

Modern experts also add a third group around Lyon, called "Arpitan" or "Franco-Provençal language", which says ouè for "yes."

The langue d'oïl group in northern France, which includes languages like Picard and Walloon, was heavily influenced by the Germanic languages of the Frankish invaders. Over time, the French language developed from either the Oïl language spoken around Paris (the Francien theory) or from a common administrative language based on all Oïl languages.

Langue d'oc languages, like Gascon and Provençal, were spoken in southern France and northern Spain. They had much less Frankish influence.

During the Middle Ages, other language groups also influenced French dialects:

- People from Cornwall, Devon, and Wales (who spoke Brythonic languages) settled in Armorica (modern Brittany) from the 4th to 7th centuries. Their language became Breton, which gave French words like bijou (jewel) and menhir (standing stone).

- A non-Celtic people who spoke a Basque-related language lived in southwestern France. Their language influenced the Latin-based language there, which became the Gascon dialect of Occitan.

- Vikings from Scandinavia invaded France from the 9th century onwards and settled in Normandy. They adopted the local langue d'oïl, but Norman French kept many words from Old Norse, especially about sailing and farming.

After the Norman conquest of England in 1066, the Normans' language became Anglo-Norman. It was the language of the rulers and business in England until the Hundred Years' War.

Around this time, many words from Arabic (or from Persian through Arabic) entered French, usually indirectly through Latin, Italian, and Spanish. These included words for luxury goods (orange), spices (safran - saffron), trade goods (alcool - alcohol), and mathematics (algèbre - algebra). Later, in the 19th century, when France had colonies in North Africa, French borrowed words directly from Arabic.

Modern French: A Language Takes Shape

For the period until about 1300, some experts call the oïl languages collectively Old French. The oldest surviving text in French is the Oaths of Strasbourg from 842 AD. Old French became a language for literature with the chansons de geste, which told stories of heroes like Charlemagne.

The first official document in Modern French was written in Aosta in 1532. In 1539, King Francis I made French the official language for government and court in France, replacing Latin. This led to a more standardized French, known as Middle French. The first grammar book for French was published in 1550. Many of the 700 modern French words from Italian came in this period, often related to art (scenario, piano) and luxury items.

From the 17th to 18th centuries, French was sometimes called Classical French. Today, many linguists simply refer to French from the 17th century onwards as Modern French.

The Académie française (French Academy) was founded in 1634 by Cardinal Richelieu. Its goal was to keep the French language pure and well-preserved. The 40 members are called "Immortals" because their founder wanted them to ensure the "immortality" of the French language. The Academy still helps guide the language, adapting foreign words. For example, they changed software to logiciel and computer to ordinateur (though the latter was by an IBM linguist, not the Academy).

From the 17th to 19th centuries, France was a major power in Europe. French became the main language for educated people across Europe, especially in arts, literature, and diplomacy. Even monarchs like Frederick II of Prussia and Catherine the Great of Russia spoke and wrote excellent French. The spread of French was also helped by Huguenots (French Protestants) who moved to other countries to escape persecution.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, French became established in the Americas. While not all early colonists from France spoke Standard French, a common French language quickly developed among them in places like New France (Canada). Today, about 10 million people in the Americas speak French.

Through the Académie, public education, and media, a unified official French language has been created. However, there are still many regional accents and words. Some people think the "best" French is spoken in Touraine, but such ideas are becoming less common as national media grows. After the 1789 French Revolution, the French government worked to unify the country by making French the common language. In 1789, only about 12-13% of French people spoke it "fairly well." Napoleon I's military service and later public education laws helped spread French and reduce local dialects.

Modern Challenges for French

Today, there's a debate in France about protecting the French language from the influence of English, especially in business, science, and popular culture. Laws like the Toubon law require French translations on ads and set quotas for French songs on the radio. Some regions and minority groups also want more support for their regional languages.

French used to be the main international language in Europe, especially for diplomacy, but it lost much of its global importance to English after World War II. The Treaty of Versailles, which ended World War I, was written in both French and English, showing this shift. Some large French companies even use English as their main working language. French scientists often publish their research in English to reach a wider audience.

These trends have faced some pushback. In 2006, President Jacques Chirac briefly left an EU summit when someone started speaking in English. Groups like Forum Francophone International protest against the dominance of English and support the right to use French at work.

French is still the second most-studied foreign language globally, after English. It remains a common language in some parts of the world, especially in Africa. While it has almost disappeared in some former French colonies (like Southeast Asia), in others, it has changed into creoles or dialects. Many former French colonies have made French an official language, and the total number of French speakers has actually increased, especially in Africa.

In the Canadian province of Quebec, laws since the 1970s have promoted French in government, business, and schools. For example, Bill 101 requires most children to be educated in French if their parents didn't attend an English-speaking school. Groups like the Office québécois de la langue française also work to preserve the unique features of Quebec French.

French immigrants moved to places like the United States, Australia, and South America. However, their descendants often adopted the local languages, and few still speak French. In the United States, efforts are being made in Louisiana and parts of New England to keep French alive.

How French Sounds Changed Over Time

French has gone through some big changes in its sounds, especially compared to other Romance languages like Spanish or Italian.

Here are some examples of how words changed from Latin to French, compared to other Romance languages:

| Latin | Written French | Spoken French | Italian | Catalan | Spanish | Portuguese | Romanian |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canis "dog" | chien | /ʃjɛ̃/ | cane | ca | can | cão | câine |

| Octō "eight" | huit | /ɥit/ | otto | vuit | ocho | oito | opt |

| Pirum "pear" | poire | /pwaʁ/ | pera | pera | pera | pera | pară |

| Adiūtāre "to help" | aider | /ɛde/ | aiutare | ajudar | ayudar | ajudar | ajuta |

One of the most noticeable things about French vowel history is how a strong stress accent developed. This likely came from the influence of Germanic languages. It caused most unstressed vowels to disappear and led to big differences in how stressed vowels were pronounced. This is why, in modern French, the stress is always on the last syllable of a word.

Vowels

In Vulgar Latin, there were five vowels in unstressed syllables. When these vowels were at the end of a word, they were mostly lost in Old French, except for 'a', which changed to a soft 'e' sound (like the 'a' in 'about').

For example:

- Latin factam (done, feminine) became French faite.

- Latin noctem (night) became French nuit.

- Latin octō (eight) became French huit.

Vowels in the middle of words that weren't stressed also disappeared.

Stressed vowels changed differently depending on whether they were in an "open syllable" (ending in a vowel sound) or a "closed syllable" (ending in a consonant sound). Many vowels in open syllables became diphthongs (two vowel sounds blended together), while others changed their sound.

Nasal Vowels

When a Latin 'n' ended up without a vowel after it, it was often absorbed into the vowel before it. This created "nasal vowels," which are sounds made by letting air out through your nose as you say the vowel.

Long Vowels

In Latin, an 's' before a consonant often caused the vowel before it to become long. In modern French, these long vowels are usually not pronounced as distinctly long anymore, but they sometimes affect the vowel's quality.

Consonants

Changes to consonants were less dramatic than to vowels. French actually kept some consonant sounds that other Romance languages changed. For example, French kept initial 'pl-', 'fl-', 'cl-' sounds, unlike Spanish or Italian.

Weakening of Consonants

Consonants between vowels often became weaker or disappeared. This process was more extensive in French than in Spanish or Italian. For example, a 't' sound between vowels in Latin eventually disappeared in French.

For example:

- Latin vītam (life) became French vie. (Compare to Italian vita, Spanish vida).

Palatalization

Over time, certain consonant sounds, especially when followed by 'e' or 'i', became "palatalized." This means they were pronounced with the middle of the tongue touching or near the hard palate, creating a 'y' sound (like in 'you') before or after them. This led to new diphthongs and complex sound changes.

For example:

- Latin pācem (peace) became French paix.

- Latin canem (dog) became French chien.

Changes to Final Consonants

In Old French, most voiced consonants (like 'd', 'g', 'b') at the end of words became voiceless (like 't', 'k', 'p'). For example, the adjective froit (cold, masculine) had a 't' sound at the end, but its feminine form froide had a 'd' sound.

In Middle French, most final consonants gradually disappeared. This is why many French words are spelled with silent letters at the end today. This also led to the modern French phenomenon of liaison, where a normally silent final consonant is pronounced when the next word starts with a vowel. For example, les halles (the markets) is pronounced without the 's' sound, but les herbes (the herbs) is pronounced with a 'z' sound.

Influences on French Grammar and Sounds

French is quite different from most other Romance languages. Some of these differences are thought to come from "substrate" influences (from Gaulish, the language spoken before Latin) or "superstrate" influences (from Frankish, the language of the Germanic invaders). It's hard to be completely sure, but here are some likely influences:

- The 'h' sound: The reintroduction of the 'h' sound at the beginning of words, mostly in words borrowed from Germanic, is due to Frankish influence. In modern French, this 'h' is usually silent, but it often prevents liaison with the previous word.

- The 'w' sound: The return of the 'w' sound in some northern French dialects (like Norman or Picard) is also from Germanic influence.

- Strong stress accent: The very strong stress accent in early French, which led to the loss of unstressed vowels and changes in stressed vowels, was likely caused by Frankish and possibly Celtic influence. This is why modern French words always have the stress on the last syllable.

- Nasal vowels: The development of nasal vowels (vowels pronounced through the nose) in French is thought to be due to Germanic and/or Celtic stress.

- Front-rounded vowels: The sounds like 'y' (as in tu) and 'eu' (as in feu) are rare in other Romance languages but common in French. They might have come from Germanic or Celtic influence.

- Weakening of consonants: The weakening of consonants between vowels (like 't' becoming silent) might be from Celtic influence, as similar changes happened in Celtic languages around the same time.

- Voiceless final consonants: The change where voiced consonants at the end of words became voiceless in Old French was caused by Germanic influence.

In terms of grammar and other features:

- Gender shifts: Some French words might have changed their gender (masculine/feminine) because of similar words in Gaulish.

- Verb-second word order: Old French often put the verb in the second position in a sentence, which was probably due to Germanic influence.

- Nous vs. on: The use of on (meaning "one" or "we" in casual speech) instead of nous (we) is similar to the Germanic impersonal pronoun man.

- Avoir (to have): French uses avoir much more than tenir (to hold/have), unlike other Romance languages. This might be influenced by the Germanic word for "have."

- Compound tenses: The increased use of auxiliary verbs to form tenses like the passé composé (e.g., j'ai mangé - I have eaten) is likely from Germanic influence. This structure is similar to what's found in Germanic languages.

- No future tense in conditional clauses: French doesn't use the future tense in "if" clauses (e.g., "If it rains, I will stay home," not "If it will rain..."). This is likely from Germanic influence.

- Counting by twenties: Old French sometimes used a base-20 counting system (like quatre-vingts for 80, meaning "four twenties"), which might have Celtic roots.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Historia del idioma francés para niños

In Spanish: Historia del idioma francés para niños

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |