History of Bavaria facts for kids

The history of Bavaria is a long and exciting journey! It tells the story of how this region, now a big state in Germany, grew from ancient settlements to a powerful kingdom and then a modern state. Long ago, Celtic people lived here. Later, the mighty Roman Empire took over, making Bavaria part of its provinces called Raetia and Noricum.

Contents

Ancient Settlements and Roman Times

Many ancient tools and signs of early humans have been found in Bavaria. The first people we know about from written records were the Celts. The Romans arrived before the time of Christianity, conquering the Celts and making their land part of the Roman provinces of Raetia and Noricum. The main Roman city in this area was Castra Regina, which is now the city of Regensburg.

Early Medieval Period and New Peoples

Around the 400s AD, the Romans living south of the Danube river faced growing pressure from groups north of the river. These new groups were Suebian people. The name "Bavarian" (in Latin, Baiovarii) actually comes from north of the Danube. It's linked to the Celtic Boii people who lived there even earlier. Over time, the name changed and was used for the people living on both sides of the Danube.

The name "Bavarian" was first written down around 520 AD in a Frankish list of peoples. The historian Jordanes mentioned them in 551 AD, saying they lived east of the Swabians. Another writer, Venantius Fortunatus, described traveling through Bavarian lands in the late 500s, warning about the dangers there.

Archaeological finds from the 400s and 500s show that many different cultures influenced the Bavarians. These included the Alamanni, Lombards, Thuringians, Goths, and Slavic people from Bohemia, as well as the local Romanized population. Historians now believe that the Bavarian identity formed because different groups came together under political and social pressures.

The First Duchy of Bavaria

The Bavarians soon came under the rule of the Franks, a powerful Germanic people. The Franks saw Bavaria as a helpful buffer zone against groups to the east, like the Avars and the Slavs. Around 550 AD, the Franks put Bavaria under the control of a duke. This duke was either a Frank or chosen from important local families. The first known duke was Garibald I, from the strong Agilolfing family. This family ruled Bavaria as dukes until 788 AD.

For about 150 years, these dukes fought off attacks from the Slavs on their eastern border. By the time Duke Theodo I died in 717, Bavaria had become quite independent from the Frankish kings. However, powerful Frankish rulers like Charles Martel and his son Pepin the Short brought Bavaria back under Frankish control.

Bavarian laws were written down between 739 and 748 AD. These laws showed some Frankish influence. They stated that while the duchy belonged to the Agilolfing family, the duke had to be chosen by the people and approved by the Frankish king, to whom he owed loyalty. The duke had important duties like leading the army, administering justice, and managing money.

Christianity Comes to Bavaria

Christianity had been present in Bavaria since Roman times, but it truly grew when Bishop Rupert of Worms arrived in 696 AD, invited by Duke Theodo I. He founded several monasteries, as did Bishop Emmeran. Soon, most people became Christian, and Bavaria began to connect with Rome. Although there was a brief return to old beliefs in the 700s, the arrival of Saint Boniface around 734 AD helped Christianity spread again. Boniface organized the Bavarian church and established or restored important bishoprics in Salzburg, Freising, Regensburg, and Passau.

Tassilo III became duke in 749. He recognized the Frankish king Pepin the Short's power in 757. But later, Tassilo started acting like an independent ruler. He made decisions about church and legal matters himself and refused to attend Frankish meetings. His control over the Alpine passes and his alliances with the Avars and the Lombard king Desiderius worried Charlemagne, the powerful Frankish king.

Charlemagne decided to stop Tassilo. Tassilo had to promise loyalty to Charlemagne in 781 and again in 787, likely because Frankish armies were nearby. But problems continued, and in 788, the Franks called Tassilo to Ingelheim and sentenced him to death for treason. Charlemagne, however, pardoned him. Tassilo entered a monastery and officially gave up his duchy in 794.

After Tassilo, Charlemagne's brother-in-law, Gerold, ruled Bavaria until his death in 799. Then, Frankish counts took over, making Bavaria part of the Carolingian empire. Charlemagne's efforts to improve education and welfare helped the region. The Bavarians did not resist this change, and their connection with the Frankish empire became very strong.

Bavaria in the Carolingian Era

For the next hundred years, Bavaria's history was tied to the Carolingian empire. In 817, Bavaria was given to Louis the German, the king of the East Franks. He made Regensburg his main city and worked hard to protect Bavaria by fighting against the Slavs. When he divided his lands in 865, Bavaria went to his oldest son, Carloman. After Carloman died in 880, Bavaria became part of the large lands ruled by Emperor Charles the Fat.

This emperor was not very good at defending the land, so he left it to Arnulf, Carloman's son. With the help of the Bavarians, Arnulf became the German king in 888. In 899, Bavaria passed to Louis the Child. During his rule, the Hungarians constantly attacked. Resistance grew weaker, and it's said that on July 5, 907, many Bavarians died fighting the Hungarians in the Battle of Pressburg.

During Louis the Child's reign, Luitpold, a count with large lands in Bavaria, ruled the border area of Carinthia, which was created to defend Bavaria. Luitpold died in the 907 battle. But his son, Arnulf, gathered the remaining Bavarians. He allied with the Hungarians and became duke of Bavaria in 911, uniting Bavaria and Carinthia. The German king, Conrad I, attacked Arnulf for not accepting his authority, but he failed.

Duchy Under New Dynasties

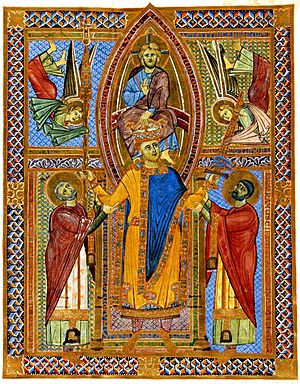

In 920, Henry the Fowler of the Ottonian family became German king. Henry recognized Arnulf as duke and allowed him to appoint bishops, coin money, and make laws.

A similar conflict happened between Arnulf's son Eberhard and Henry's son Otto I the Great. Eberhard was not as successful as his father and fled Bavaria in 938. Otto then gave the duchy (with fewer privileges) to Arnulf's uncle, Bertold. Otto also appointed a special official, Arnulf, to protect the king's interests.

When Bertold died in 947, Otto gave the duchy to his own brother, Henry, who had married Duke Arnulf's daughter, Judith. The Bavarians didn't like Henry, and he spent his short rule arguing with them.

The Hungarian attacks stopped after their defeat at the Lechfeld in 955. For a while, Bavaria even gained some land in Italy.

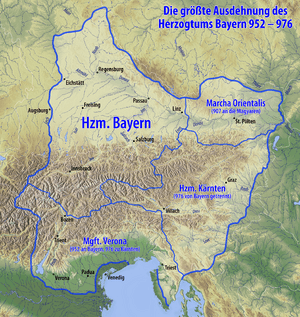

In 955, Henry's young son Henry, known as "the Quarrelsome," became duke. But in 974, he joined a plot against King Otto II. This happened because the king had given the Duchy of Swabia to Henry's enemy, Otto, a grandson of Emperor Otto the Great. Also, the new Bavarian Eastern March, later called Austria, was given to Leopold of Babenberg. The revolt failed, and Henry lost his Duchy of Bavaria in 976.

At the same time, Carinthia became a separate duchy, and the Bavarian church became more dependent on the king instead of the duke. Bavaria at this time included the Inn basin (with Salzburg) and the Danube river area. Important Bavarian cities were Freising, Passau, Salzburg, and Regensburg.

Henry was restored as duke in 985 and proved to be a good ruler. He brought order, made important laws, and reformed monasteries. In 1002, his son Henry II gave Bavaria to his brother-in-law Henry of Luxembourg. After Henry's death in 1026, Bavaria passed to other rulers, including Henry III, who later became emperor. In 1061, Empress Agnes, who was ruling for her young son Henry IV, gave the duchy to Otto of Nordheim.

Under the Welf Family

In 1070, King Henry IV removed Duke Otto and gave the duchy to Count Welf. He was from an important Bavarian family with roots in northern Italy.

Welf supported Pope Gregory VII in his conflict with King Henry, so he lost Bavaria but later got it back. Two of his sons, Welf II (from 1101) and Henry IX (from 1120), followed him as dukes. They were both very influential among the German princes.

Henry IX's son, Henry X, called "the Proud," became duke in 1126. He also gained the Duchy of Saxony in 1137. King Conrad III was worried about Henry's power and didn't want one person to hold two duchies, so he declared Henry removed. He gave Bavaria to Leopold IV, the Margrave of Austria. When Leopold died in 1141, the king kept the duchy himself. But there was still a lot of unrest, so in 1143, he gave it to Henry, also known as Jasomirgott.

The fight for Bavaria continued until 1156. Emperor Frederick I wanted peace in Germany. He convinced Henry to give up Bavaria to Henry the Lion, who was the duke of Saxony and Henry the Proud's son. In return, Austria was made an independent duchy. It was Henry the Lion who founded the city of Munich.

Changing Borders

After the Carolingian empire broke up, Bavaria's borders kept changing. For a long time after 955, Bavaria actually started to grow. To the west, the Lech river still separated Bavaria from Swabia. But on other sides, Bavaria expanded, gaining a large area north of the Danube. However, later on, Bavaria began to shrink again.

In 1027, Emperor Conrad II separated the Bishopric of Trent from the Kingdom of Italy and added it to Bavaria. But over time, counts living near Merano in Castle Tyrol gained more power and became independent from Bavaria. When Henry X the Proud was removed as duke in 1138, the Counts of Tyrol became even more independent. By 1154, Tyrol was no longer considered part of Bavaria.

Duke Henry the Lion focused more on his northern duchy of Saxony than on Bavaria. When the dispute over Bavaria ended in 1156, the land between the Enns and the Inn rivers became part of Austria.

Other former Bavarian territories, like the March of Styria (which became a duchy in 1180) and the county of Tyrol, became more important. This reduced Bavaria's power and limited its chances to expand. Neighboring areas like the Duchy of Carinthia and the large lands of the Archbishopric of Salzburg, along with nobles wanting more independence, all restricted Bavaria's growth.

Under the Wittelsbach Family

A new chapter began in 1180 when Emperor Frederick I gave the duchy of Bavaria to Otto. He was from the old Bavarian family of Wittelsbach and a descendant of the counts of Scheyern. The Wittelsbach family would rule Bavaria without interruption until 1918! They also gained the Electorate of the Palatinate in 1214.

When Otto of Wittelsbach took over Bavaria in 1180, the duchy's borders were the Böhmerwald, the Inn river, the Alps, and the Lech river. The duke mostly controlled his own large private lands around Wittelsbach, Kelheim, and Straubing.

Otto only ruled Bavaria for three years. His son Louis I took over in 1183. Louis played an important role in German affairs until he was killed in 1231. His son Otto II, called "the Illustrious," remained loyal to the Hohenstaufen emperors. Like his father, Otto II bought more land and made his control over the duchy stronger. He died in 1253.

Bavaria Divided

The dukes tried hard to increase their power and unite Bavaria. But their efforts were soon undone by divisions among different family members. For 250 years, the history of Bavaria was mostly a story of land being split up, which led to wars and weakness.

The first split happened in 1255. Louis II and Henry XIII, the sons of Duke Otto II, had ruled Bavaria together for two years. Then they divided their inheritance: Louis II got the western part, later called Upper Bavaria, and the Electorate of the Palatinate. Henry got eastern or Lower Bavaria.

These divisions led to many conflicts and weakened Bavaria's position in German politics. Neighboring states took advantage, and nobles often ignored the dukes. However, this period of disorder also had some good effects. The government and finances were increasingly managed by an assembly called the Landtag. Towns became strong and wealthy as trade grew, and citizens of cities like Munich and Regensburg often challenged the dukes. So, even with the disorder, representative institutions and a strong civic spirit grew.

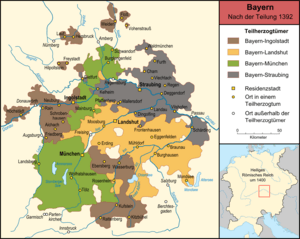

By 1392, a major division took place, splitting most of the duchy among three sons of Stephen II: Stephen III, Frederick, and John II. They founded the lines of Ingolstadt, Landshut, and Munich.

The duchy of Bavaria-Straubing, which included Holland and Hainaut, eventually became extinct in 1425. After some disputes, the other three branches of the Wittelsbach family (Ingolstadt, Landshut, and Munich) divided Bavaria-Straubing among themselves.

The Ingolstadt line ended in 1447, and its lands passed to the Landshut line. The Landshut line ended in 1503, leading to a war of succession.

Bavaria Reunited

The Bavaria-Munich line continued. After some joint rule, Albert III became the sole ruler in 1440. He was known for trying to reform monasteries. His son, Albert IV, called "the Wise," added the district of Abensberg to his lands. In 1504, he was involved in the Landshut War of Succession over the lands of George the Rich.

After the war, in 1505, an agreement was made. Albert gained most of George's lands, which helped to unite Bavaria under his rule. In 1506, Albert made an important rule: the duchy would now pass to the eldest son only (primogeniture). This helped to keep Bavaria together and prevent future divisions. He also worked to improve the country. In 1500, Bavaria became one of the six main regions of Germany, helping to keep the peace. Albert died in 1508, and his son, William IV, became duke.

The Reunited Duchy

Renaissance and Counter-Reformation

Even with the new rule of primogeniture, William IV had to share power with his brother Louis X until Louis died in 1545.

William IV initially opposed the powerful Habsburg family but later allied with them. This alliance grew stronger when Emperor Charles V got William's help during a war, promising him a chance to inherit the Bohemian throne and the important electoral title. William also played a big role in keeping Bavaria Catholic. He gained rights over bishoprics and monasteries from the pope and then took steps to stop the Protestant Reformation. Many reformers were banished. In 1541, he invited the Jesuits to Bavaria, and their college in Ingolstadt became a major center for them in Germany. William died in 1550, and his son Albert V took over.

Albert V, who married a daughter of Emperor Ferdinand I, initially made some small allowances for reformers. But around 1563, he changed his mind. He supported the decisions of the Council of Trent and pushed forward the Counter-Reformation. As education increasingly came under Jesuit control, the spread of Protestantism was effectively stopped in Bavaria.

Albert V was a great supporter of art. Artists came to his court in Munich, and beautiful buildings were constructed. He collected many artworks from Italy and other places. However, the costs of his grand court led him to argue with the nobles, burden his people with taxes, and leave a lot of debt when he died in 1579.

His son, William V, known as "the Pious," had a Jesuit education and was very devoted to their teachings. He helped his brother Ernest become Archbishop of Cologne in 1583, a position the family held for almost 200 years. In 1597, William V gave up his rule to his son Maximilian I and retired to a monastery.

The Thirty Years' War

When Maximilian I became duke, Bavaria was in debt and disorder. But in just ten years, his strong rule brought amazing changes. He reorganized the finances and legal system, created a group of civil servants, and started a national militia. He also brought several small areas under his control. This brought unity and order to Bavaria, allowing Maximilian to play a big role in the Thirty Years' War. In the early years of the war, he was so successful that he gained the Upper Palatinate and the important electoral title, which had belonged to an older branch of the Wittelsbach family since 1356. Even after some setbacks, Maximilian kept these gains in the Peace of Westphalia in 1648.

During the later years of the war, Bavaria, especially the northern part, suffered greatly. In 1632, the Swedes invaded. When Maximilian broke a treaty in 1647, the French and Swedes devastated the land. After repairing some of this damage, Maximilian died in 1651. He left his duchy much stronger than he found it. Gaining the Upper Palatinate made Bavaria more compact, and getting the electoral vote made it influential. Bavaria could now play a role in European politics, something internal conflicts had prevented for 400 years.

The Electorate of Bavaria

Absolute Rule

The strong international position that Maximilian I achieved for Bavaria had mixed effects on the duchy itself for the next two centuries. Maximilian's son, Ferdinand Maria (1651–1679), who was young when he became ruler, tried to heal the wounds from the Thirty Years' War. He encouraged farming and industries and built or restored many churches and monasteries. In 1669, he even called a meeting of the diet (assembly), which had not met since 1612.

However, his good work was largely undone by his son Maximilian II Emanuel (1679–1726). Maximilian II Emanuel was very ambitious and led Bavaria into wars against the Ottoman Empire and, on the side of France, in the major Spanish Succession War. He was defeated at the Battle of Blenheim in 1704. His lands were temporarily divided between Austria and the elector palatine. Bavaria was only returned to him, damaged and exhausted, by the Treaty of Baden in 1714. The first Bavarian peasant rebellion, known as the Bloody Christmas of Sendling, had been crushed by Austrian forces in 1706.

Not learning from his father's mistakes, Maximilian II Emanuel's son, Charles Albert (1726–1745), focused all his energy on increasing Bavaria's power and fame in Europe. When Emperor Charles VI died, Charles Albert saw his chance. He challenged the rule that secured the Habsburg succession to Maria Theresa. He allied with France, conquered Upper Austria, was crowned king of Bohemia in Prague, and in 1742, became emperor in Frankfurt. But the cost was high: Austrian troops occupied Bavaria itself. Although an invasion of Bohemia by Frederick II of Prussia allowed him to return to Munich in 1744, when he died in 1745, it was up to his successor to make peace and get Bavaria back.

Maximilian III Joseph (1745–1777), known as "Max the much-beloved," signed the peace treaty of Füssen in 1745. He got his lands back in return for formally accepting Maria Theresa's right to rule. He was an "enlightened" ruler who did much to help farming, industries, and mining. He founded the Academy of Sciences in Munich and ended the Jesuit censorship of the press. However, he also signed more death sentences than any ruler before him. When he died in 1777, the Bavarian line of the Wittelsbachs ended. The rule passed to Charles Theodore, the elector palatine. After 450 years, the Electorate of the Palatinate, which included the duchies of Jülich and Berg, was reunited with Bavaria.

Revolutionary and Napoleonic Times

In 1792, French revolutionary armies took over the Palatinate. In 1795, the French, led by Moreau, invaded Bavaria itself and reached Munich. They were welcomed by people who wanted more freedom. Charles Theodore, who had done nothing to stop the wars or the invasion, fled to Saxony. A temporary government signed a deal with Moreau, agreeing to a ceasefire in exchange for a large payment in 1796.

Bavaria was now caught between the French and the Austrians. Even before Charles Theodore died in 1799, the Austrians had occupied Bavaria again, preparing for war with France. The new elector, Maximilian IV Joseph, inherited a difficult situation. Although he and his powerful minister, Maximilian von Montgelas, favored France over Austria, Bavaria's finances were bad, and its troops were scattered. This left Bavaria helpless in Austria's hands. In 1800, Bavarian armies were involved in the Austrian defeat at Hohenlinden, and Moreau again occupied Munich. By the Treaty of Lunéville (1801), Bavaria lost the Palatinate and the duchies of Zweibrücken and Jülich.

Seeing Austria's clear ambitions, Montgelas believed Bavaria's best interest was to ally with France. He convinced Maximilian Joseph, and a separate peace and alliance treaty with France was signed in Paris in 1803. As a result, Bavaria received new territories, including the bishoprics of Würzburg, Bamberg, Augsburg, and Freisingen, parts of Passau, and lands from several abbeys and cities. This new compact territory more than made up for the lost lands on the Rhine. Montgelas now aimed to make Bavaria a major power. He skillfully pursued this goal during the time of Napoleon, always recognizing France's dominance but never letting Bavaria become a mere French puppet state.

In the War of the Third Coalition in 1805, Bavarian troops fought alongside the French for the first time since the days of Charles VII. By the Treaty of Pressburg (1805), Bavaria gained more land, including the Principality of Eichstädt, Margraviate of Burgau, Vorarlberg, and the city of Lindau. However, Würzburg, which Bavaria had gained in 1803, was given to the elector of Salzburg in exchange for Tirol. The treaty also recognized Maximilian as King, and he became Maximilian I. As a price for this new title, Maximilian reluctantly agreed to his daughter Augusta marrying Eugène de Beauharnais, Napoleon's stepson. In 1806, he gave the Duchy of Berg to Napoleon.

The alliance with France also brought important changes to Bavaria's internal government. Maximilian was an "enlightened" ruler who believed in tolerance. Montgelas strongly believed in major reforms from the top down. In 1808, a new constitution was put in place, largely due to Napoleon's influence. It swept away old medieval laws and privileges. Instead, it established equality before the law, universal taxation, the end of serfdom, security of person and property, and freedom of conscience and the press. A representative assembly was planned, but it was never actually called.

In 1809, Bavaria was again at war with Austria, fighting with France. The Tyroleans rose up against Bavarian rule and defeated Bavarian and French troops three times. Austria lost the war against France and faced even harsher terms in the Treaty of Schönbrunn in 1809. Andreas Hofer, the leader of the Tyrolean uprising, was executed in 1810 after losing a final battle. By a treaty signed in Paris in 1810, Bavaria gave southern Tirol to Italy and some small areas to Württemberg. In return, it received parts of Salzburg, the Innviertel, and the principalities of Bayreuth and Regensburg. Montgelas's policy had been very successful.

However, Napoleon's power was now at its peak, and Montgelas saw signs of change. After the events of 1812, Bavaria was asked to join the alliance against Napoleon in 1813. Crown Prince Louis and Marshal Wrede strongly supported this. On October 8, the treaty of Ried was signed, and Bavaria joined the Allies. Montgelas told the French ambassador that he had to temporarily give in to the storm, adding, "Bavaria needs France."

The Kingdom of Bavaria

Constitution and Revolution

Right after the first peace of Paris in 1814, Bavaria gave northern Tyrol and Vorarlberg to Austria. During the Congress of Vienna, it was decided that Bavaria would also give up most of Salzburg and the Innviertel. In return, Bavaria received Würzburg, Aschaffenburg, the Palatinate (region) on the left bank of the Rhine, and some districts from Hesse-Darmstadt and the former Abbacy of Fulda. But with France's defeat, old fears and rivalries with Austria returned. Bavaria only agreed to these land changes (in the treaty of Munich, 1816) because it was promised compensation if its claim to the Baden succession was ignored. This issue remained open, and tensions between Bavaria and Austria stayed high.

Meanwhile, on February 1, 1817, Montgelas was dismissed. Bavaria entered a new period of constitutional reform. This didn't mean a change in its European policy. In the new German confederation, Bavaria aimed to protect smaller states from Austria and Prussia. Montgelas had dreamed of Bavaria leading southern Germany, similar to Prussia in the north. Crown Prince Louis pushed for a liberal constitution to gain public support for this policy and Bavaria's claims on Baden. Montgelas's hesitation to grant it led to his dismissal.

On May 26, 1818, the constitution was announced. The parliament would have two houses. The first included wealthy landowners, government officials, and people chosen by the king. The second, elected by a small group of voters, had representatives of small landowners, towns, and peasants. Additional rules guaranteed equal rights for all religions and protected Protestants. These concessions were criticized by Rome as breaking a recent agreement. The new constitution didn't quite meet royal expectations. When parliament opened in 1819, some members were very radical, even demanding the army swear loyalty to the constitution. This alarmed the king, who asked Austria and Germany for help. However, Prussia refused to support a sudden change in government. The parliament, realizing its survival depended on the king, became more moderate. Maximilian ruled as a good constitutional monarch until his death. On October 13, 1825, his son Ludwig I became king.

Ludwig was an enlightened supporter of arts and sciences. He moved the University of Landshut to Munich, which he transformed into one of Europe's most beautiful cities with his magnificent building projects. The early years of his reign were liberal, especially in financial administration. But the revolutions of 1830 scared him into a more conservative approach, which was made worse by parliament's opposition to his spending on buildings and art. In 1837, the Ultramontanes (a Catholic group) came to power with Karl von Abel as prime minister. The Jesuits gained influence, and the liberal parts of the constitution were changed or removed. Protestants were harassed, and strict censorship prevented free discussion of politics. This system collapsed not because of public protest, but because Ludwig was angry about the church's opposition to his mistress, Lola Montez. On February 17, 1847, Abel was dismissed for opposing Lola's naturalization. The new ministry granted it, but riots broke out, involving university professors. The professors were removed, parliament was dissolved, and the ministry was dismissed. Lola Montez, now Countess Landsfeld, became very powerful. The new minister, Prince Ludwig of Öttingen-Wallerstein, tried to gain liberal support but couldn't form a stable government. His cabinet was known as the Lolaministerium. In February 1848, news from Paris (the Revolution of 1848 in France) sparked riots against the countess. On March 11, the king dismissed Öttingen, and on March 20, realizing public opinion was against him, he gave up his throne to his son, Maximilian II.

Before abdicating, Ludwig had promised Bavaria's support for German freedom and unity. Maximilian II was loyal to this idea, accepting the authority of the central government in Frankfurt. But Prussia became the enemy, not Austria. Maximilian refused the offer of the imperial crown to Frederick William IV, and his parliament supported him. He also refused to agree to the new German constitution that excluded Austria from the Confederation. By this time, the revolution was mostly over. In the events that led to Prussia's humiliation at Olmütz in 1851 and the return of the old Confederation, Bavaria sided with Austria.

The main person behind this anti-Prussian policy was Baron Karl Ludwig von der Pfordten (1811–1880), who became foreign minister in 1849. He wanted a league of the Rhenish states to balance the power of Austria and Prussia. In internal affairs, his ministry was conservative but less harsh than elsewhere in Germany. This led to a struggle with parliament from 1854, ending in Pfordten's dismissal in 1859. He was replaced by Karl Freiherr von Schrenk von Notzing, a liberal official. Important reforms were introduced, like separating judicial and executive powers and creating a new criminal code. In foreign affairs, Schrenk, like his predecessor, aimed to protect Bavaria's independence. Bavaria opposed Prussia's plans to reorganize the Confederation. One of King Maximilian's last acts was to play a big part in the assembly of princes called to Frankfurt in 1863 by Emperor Francis Joseph.

Maximilian was succeeded on March 10, 1864, by his son Ludwig II, who was eighteen. The government was initially run by Schrenk and Pfordten together. Schrenk soon retired when Bavaria had to join Prussia's trade treaty with France to maintain its position in the Prussian customs union. In the complex Schleswig-Holstein question, Bavaria, guided by Pfordten, consistently opposed Prussia and led the smaller states in supporting Frederick of Augustenburg. Finally, in the war of 1866, despite Bismarck's efforts to keep Bavaria neutral, Bavaria actively sided with Austria.

The German Empire

Prussia's quick victory and Bismarck's wise moderation completely changed Bavaria's relationship with Prussia and the German question. The South German Confederation that was planned never happened. Although Prussia didn't want the southern states to join the North German Confederation (to avoid alarming France), Bavaria's ties with the north grew stronger. This happened through a defensive alliance with Prussia, made after Napoleon demanded "compensation" in the Palatinate. This alliance was signed in Berlin in 1866, the same day as the peace treaty between the two countries. Bavaria formally gave up its desire to be separate. It no longer "needed France." During the Franco-Prussian War, the Bavarian army marched under the Prussian crown prince against Germany's common enemy. It was King Ludwig II who suggested offering the imperial crown to King Wilhelm I of Prussia.

Before this, on November 23, 1870, Bavaria and the North German Confederation signed a treaty. By this agreement, Bavaria became a full part of the new German empire, but it kept more independent power than any other state. For example, it kept its own diplomatic service, military administration, and postal, telegraph, and railway systems. The Bavarian parliament approved the treaty in 1871, though there was strong opposition from the "Patriot Party." Their opposition grew because of the Kulturkampf, a conflict between the state and the Catholic Church, caused by the declaration of papal infallibility in 1870. Munich University, where Ignaz von Döllinger was a professor, became a center of opposition to the new church teaching. The Old Catholics were protected by the king and government. The federal law expelling the Jesuits was announced in Bavaria in 1871 and extended to the Redemptorists in 1873. By 1871, Bavaria had also accepted many laws from the North German Confederation, including a new criminal code, which was put into force in Bavaria in 1879. The Patriot Party's opposition, strengthened by the strong Catholic feelings in the country, continued. Only the king's steady support for Liberal ministries prevented disastrous outcomes in parliament, where the Patriot Party (later the Centre Party) remained a majority until 1887.

Ludwig II's passion for building palaces and his neglect of government duties became a serious problem. He was declared insane, and on June 10, 1886, his uncle, Prince Luitpold, became regent. Three days later, on June 13, Ludwig II was found dead in Lake Starnberg. It's still not clear if his death was self-inflicted, accidental, or caused by others. Because Ludwig's brother, King Otto I, was also insane, Prince Luitpold continued as regent.

After 1871, Bavaria fully shared in Germany's rapid development. But its unique identity, based on traditional differences and religious feelings towards the Prussians, was not gone. It showed itself in small ways, like a rule (reissued in 1900) that only the Bavarian flag could be displayed on public buildings on the emperor's birthday. This rule was later changed to allow both the Bavarian and imperial flags to be flown together.

After Prince Luitpold died in 1912, his son, Prince Ludwig, became regent. A year later, Ludwig removed his cousin Otto and declared himself King Ludwig III of Bavaria. During World War I, Ludwig's oldest son, Crown Prince Rupprecht, commanded the Bavarian army and became one of Germany's top commanders on the Western Front.

Bavaria in Modern Times

Bavaria During the Weimar Republic

After the upheavals of November 1918, royal rule in Bavaria was replaced by republican institutions. Provisional National Council Minister-President Kurt Eisner declared Bavaria a free state on November 8, 1918. Eisner was killed on February 21, 1919. This eventually led to a Communist uprising and the short-lived Bavarian Socialist Republic (also called Bayerische Räterepublik) being declared on April 6, 1919. After being violently put down by parts of the German Army and especially the Freikorps, the Bavarian Socialist Republic fell on May 3, 1919. The Bamberg Constitution (Bamberger Verfassung) was put into effect on August 14, 1919, creating the Free State of Bavaria within the Weimar Republic.

Munich became a center for extreme political groups. The 1919 Bavarian Soviet Republic and the 1923 Beer Hall Putsch, involving Erich Ludendorff and Adolf Hitler, both happened in Munich. However, for most of the Weimar Republic, Bavaria was dominated by the generally conservative Bavarian People's Party (BPP). The BPP was a Catholic party that represented Bavaria's traditional conservative views, and it often expressed monarchist and even separatist feelings. An attempt in 1932, supported by many parties, to make Rupprecht, Crown Prince of Bavaria, a powerful "State Commissioner" to counter the Nazis failed because the Bavarian government under Heinrich Held was hesitant.

Bavaria During the Nazi Era

When the Nazis came to power in 1933, the Bavarian parliament was dissolved without new elections. Instead, seats were given based on the national election results of March 1933. This gave the Nazis and their allies a small majority because the seats won by the KPD were declared invalid. With this control, the Nazi Party (NSDAP) was declared the only legal party, and all other parties in Germany and Bavaria were dissolved. In 1934, the Bavarian parliament, like all other state parliaments, was also dissolved. Soon after, Bavaria itself was broken up during the reorganization of the Reich. Instead of states, Reichsgaue were created as administrative regions. Bavaria was split into six regions: Schwaben, München-Oberbayern, Bayerische Ostmark, Franken, Main-Franken, and Westmark.

During the 12 years of Nazi rule, Bavaria was one of Hitler's favorite places. He spent a lot of time at his home on the Obersalzberg. The KZ in Dachau, near Munich, was the first concentration camp established. But Bavaria was also a place of quiet resistance against the regime, the most famous example being the White Rose group. Nürnberg, Bavaria's second-largest city, became the site of huge Nazi rallies, the Reichsparteitage. Ironically, the last one planned for 1939, called Reichsparteitag des Friedens (Reichsparteitag of peace), was canceled because World War II began. After the war, Nürnberg was chosen to host the war crimes trials, known as the Nuremberg Military Tribunals.

At the start of the 1900s, about 54,000 Jewish people lived in Bavaria. By 1933, 41,000 still lived there. By 1939, this number had shrunk to 16,000. Few of those survived the Nazi rule.

Bavaria in the Federal Republic of Germany

After World War II ended, US forces occupied Bavaria. They reestablished the state on September 19, 1945. In 1946, Bavaria lost its district on the Rhine, the Palatinate. The destruction from aerial bombings during the war, along with the arrival of refugees from parts of Germany now under Soviet control, caused big problems for the authorities. By September 1950, 2,155,000 displaced people had found refuge in Bavaria, making up almost 27 percent of the population. Many of these were Sudeten Germans from Bohemia and Moravia, and Germans from Silesia. Another large group were German-speakers from Hungary. In the following decades, Sudeten Germans were recognized as Bavaria's fourth largest ethnic group, alongside Bavarians, Franconians, and Swabians.

Bavaria is home to the Bavarian Party, founded in 1946, which aims to establish an independent Bavarian state. For a time, the idea of Bavaria becoming independent again was seriously considered by the Allied occupation forces, along with a possible union between Bavaria and Austria. With the start of the Cold War, support for Bavarian independence faded both within Bavaria and from the Western allies. Bavaria became one of the states of the new Bundesrepublik (Federal Republic of Germany) in 1949.

Three years earlier, the first state elections after World War II were held on June 30, 1946. The main task of the elected delegates was to write a new Bavarian constitution, as the US authorities still managed the state day-to-day. The new constitution was accepted by public vote on December 1, 1946. On the same day, the first post-war state parliament (German: Landtag) was elected. Bavaria was politically dominated by the Christian Social Union (CSU), a sister party of the Christian Democratic Union, which is Germany's main center-right party, until 1954. Bavaria was then governed by a coalition led by the Social Democratic Party of Germany, returning to the CSU in 1957.

Since the 1960s, Bavaria has grown dynamically to become one of Europe's leading economic regions. The state is no longer mainly an agricultural area but is home to many high-tech industries.

After the CSU lost more than 17% of the votes in the Bavarian state elections of 2008, the current Minister-President Günther Beckstein and CSU Chairman Erwin Huber announced their resignations. Horst Seehofer was quickly suggested as their replacement. At a party meeting on October 25, he was confirmed as the new CSU Chairman. On October 27, he was elected Minister-President by the Landtag with votes from the Free Democratic Party. This formed the first coalition government in Bavaria since 1962.

In 2008, Bavaria became the first German state to completely ban smoking in bars and restaurants. After some CSU members criticized this as "too harsh," it was relaxed a year later. Supporters of smoking bans then called for a public vote on the issue, which led to even stricter rules than the first ban. A more complete ban was then introduced in 2010.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Baviera para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Baviera para niños

- List of rulers of Bavaria

- List of ministers-president of Bavaria

- Kingdom of Bavaria

- History of Franconia

- Haus der Bayerischen Geschichte: Museum

- History of cities in Bavaria

- Timeline of Augsburg

- History of Munich and Timeline of Munich

- Timeline of Nuremberg

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |