Morea expedition facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Expedition of the Morea |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Greek War of Independence | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| - Nicolas Joseph Maison (military expedition) - Jean Baptiste Bory de Saint-Vincent (scientific expedition) |

- Ibrahim Pasha of Egypt | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1,500 dead | unknown | ||||||

The Morea Expedition was when the French Army helped Greece between 1828 and 1833. This happened during the Greek War of Independence. The main goal was to remove the Ottoman-Egyptian forces from the Peloponnese region. A group of scientists also joined the expedition. They were sent by the French Academy to study the area.

After the city of Messolonghi fell in 1826, European powers decided to help Greece. They wanted to force Ibrahim Pasha to leave the Peloponnese. Ibrahim Pasha was an ally of the Ottoman Empire. In October 1827, a combined fleet from France, Russia, and Britain destroyed the Turkish-Egyptian fleet at the Battle of Navarino.

In August 1828, a French army of 15,000 soldiers landed in the Peloponnese. They were led by General Nicolas-Joseph Maison. By October, the French soldiers had taken control of the main forts held by Turkish troops. Most of the French troops went home in early 1829. However, some French soldiers stayed until 1833. About 1,500 French soldiers died, mostly from fevers and dysentery.

A group of scientists also went with the French army. This was similar to Napoleon's Egyptian Campaign. The scientific group was called the Expédition scientifique de Morée. It was overseen by three academies of the Institut de France. Jean-Baptiste Bory de Saint-Vincent led the group. Nineteen scientists joined, studying natural history, archaeology, and architecture-sculpture. They arrived in Greece in March 1829 and stayed for about nine months. Their work was very important for the new Greek state. It also helped modern archaeology, map-making, and natural sciences.

Contents

- Why France Helped Greece

- The Military Expedition

- The Scientific Expedition

- Publications of the Morea Expedition

- Images for kids

Why France Helped Greece

The Greek Fight for Freedom

In 1821, the Greeks started a rebellion against the Ottoman Empire. The Ottomans had ruled Greece for centuries. The Greeks won some early battles and declared their independence in 1822. However, this went against the rules set by European powers at the Congress of Vienna. These rules wanted to keep things as they were.

Some European countries had different ideas about helping Greece. Austria did not like the Greek rebellion. Russia supported the Greeks because they shared the same Christian religion. Russia also wanted more control over important sea routes. France had a mixed view. They had fought against rebels in Spain, but they saw the Greeks as fellow Christians fighting against Muslims. Great Britain, a liberal country, was interested because Greece was on the way to India. All of Europe also saw Greece as the birthplace of Western civilization and art.

Greece's Struggles and European Help

The Greeks' early victories did not last long. The Ottoman Sultan asked for help from Muhammad Ali, his ally in Egypt. Muhammad Ali sent his son, Ibrahim Pasha, with a large army. Ibrahim's army was very strong. They took back much of the Peloponnese in 1825. Messolonghi fell in 1826, and Athens was captured in 1827. Only a few areas remained under Greek control.

Many people in Western Europe felt sympathy for the Greeks. This feeling was called philhellenism. It grew stronger after the fall of Messolonghi in 1826. Famous artists and writers like Victor Hugo and Eugène Delacroix supported the Greek cause. Their works, like Delacroix's paintings, made public opinion stronger.

Eventually, European powers decided to help Greece. They saw Greece as a Christian outpost in the East. Its location was also very important. By the Treaty of London in 1827, France, Russia, and the United Kingdom recognized Greece's independence. Greece would still be a part of the Ottoman Empire, but it would govern itself. The three powers agreed to send a naval force. This force would pressure the Ottomans to accept the treaty.

The Battle of Navarino happened in October 1827. The combined French, Russian, and British fleet completely destroyed the Turkish-Egyptian fleet. This put Ibrahim Pasha in a difficult spot. He could not get supplies or new soldiers. His own troops were leaving.

In August 1828, an agreement was signed. It said Ibrahim Pasha had to leave the Peloponnese. But he refused to follow the agreement. He kept control of several Greek areas. He even ordered the destruction of Tripolitza. The French government, led by Charles X, decided to send a land army. Great Britain did not want to send its own troops. Russia had already declared war on the Ottoman Empire. This made Britain worried about Russia gaining too much power. So, Britain did not stop France from acting alone.

Ideas and Ancient Greece

The Enlightenment period made Europeans very interested in Greece. They especially admired Ancient Greece. They saw it as the foundation of Western civilization. Philosophers believed that ancient Athens had values like nature and reason. They looked to ancient Greek democracies as models.

Writers like Abbé Barthélemy helped shape Europe's image of Greece. His book Voyage du Jeune Anacharsis (1788) made people think of an ideal Aegean.

Johann Joachim Winckelmann also greatly influenced how Europeans viewed ancient art. His book History of Ancient Art (1764) divided ancient art into periods. He believed Greek art reached its peak during a time of freedom. This idea made Europeans want to visit modern Greece. They believed "good taste" came from the Greek sky.

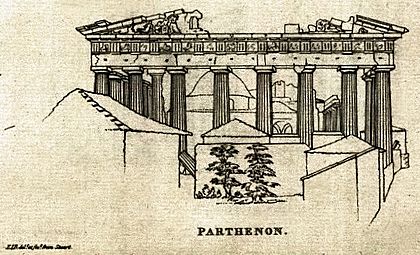

The French government planned the Morea expedition to continue earlier scientific work. Expeditions by James Stuart and Nicholas Revett had tried to rediscover ancient Greece. Their work, The Antiquities of Athens, inspired new Greek-style architecture. Later, Lord Elgin took sculptures from the Parthenon to Britain. This made people want to collect ancient art in Europe.

The Military Expedition

Much of what we know about the Morea expedition comes from soldiers who were there. These include Louis-Eugène Cavaignac, Alexandre Duheaume, Jacques Mangeart, and Doctor Gaspard Roux.

Getting Ready for Battle

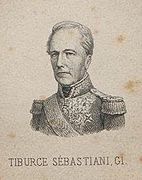

The French government approved money for the expedition. An army of 13,000 to 15,000 men was formed. Lieutenant-General Nicolas Joseph Maison led them. The army had nine infantry regiments. These were divided into three brigades. Generals Tiburce Sébastiani, Philippe Higonet, and Virgile Schneider commanded these brigades. General Antoine Simon Durrieu was the Chief of Staff.

The army also had cavalry, artillery, and engineers. A fleet of sixty ships carried the soldiers and supplies. They brought equipment, food, weapons, and money for the Greek government. France wanted to help the new Greek state build its own army. This would also increase France's influence in the region.

The first group of ships left Toulon on August 17. General Maison was on the ship Ville de Marseille. The other groups followed a few days later.

Fighting in the Peloponnese

Landing in Greece

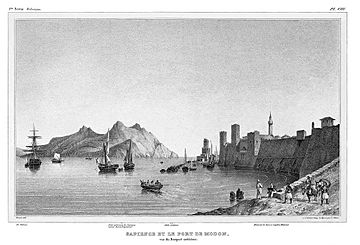

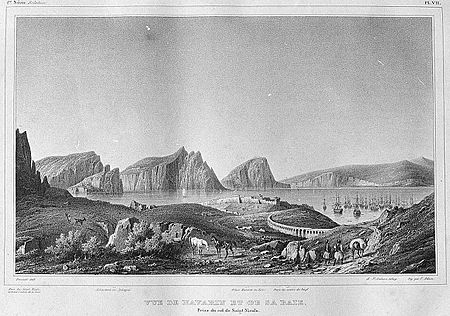

The first French ships arrived in Navarino Bay on August 28. The Egyptian army was between Navarino and Methoni. General Maison met with Admiral Henri de Rigny. They decided to land the troops in the Messenian Gulf. The landing began on August 29 and finished on August 31. There was no resistance.

The soldiers set up camp north of Koroni. The Greek governor, Ioannis Kapodistrias, had told the people the French were coming. Locals welcomed the troops and offered them food. The third brigade landed on September 22. They joined the other brigades near Navarino.

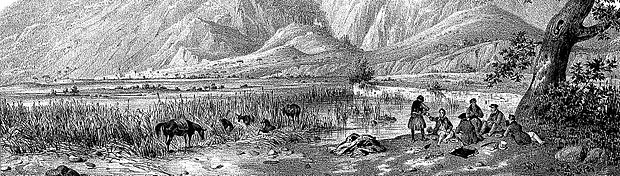

When the French arrived, they saw a country destroyed by Ibrahim's troops. Villages were burned, crops were ruined, and people were starving.

I saw the most terrible sight of my life. Outside the city (Navarino), which was in ruins, were men, women, and children. They looked like they had nothing human left. Some had no noses, others no ears. All were covered in scars. But what moved us most was a four-year-old child whose eyes had been gouged out. Turks and Egyptians spared no one. — Amaury-Duval

Egyptian Army Leaves

Ibrahim Pasha was supposed to leave the Peloponnese. But he kept finding excuses to delay. The French soldiers were getting impatient. They also started getting sick from fevers and dysentery. General Maison wanted his men to be in proper barracks.

On September 7, Ibrahim Pasha finally agreed to leave. His troops could take their weapons and belongings. But they could not take any Greek slaves or prisoners. The first group of 5,500 Egyptian soldiers left on September 16. The French troops moved closer to Navarino. On October 1, General Maison reviewed his troops. Ibrahim Pasha and Greek General Nikitaras were there.

The last Egyptian ships left on October 5, taking Ibrahim Pasha with them. Out of 40,000 men he brought, only 21,000 returned. About 2,500 Ottoman soldiers remained in the Peloponnese. The French army's next job was to secure these forts and give them back to Greece.

French Troops Take Forts

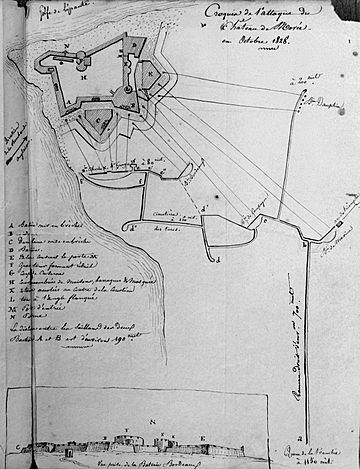

General Nicolas Joseph Maison sent reports about taking the forts in October 1828.

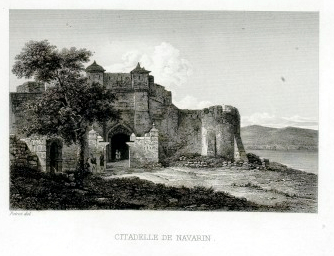

On October 6, General Maison ordered General Philippe Higonet to march on Navarino. Admiral Henri de Rigny's fleet blocked the sea. The Turkish commander refused to surrender. He said they were not at war with France or England. But the French engineers broke through the walls. General Higonet entered the fortress. The 530 Turkish soldiers surrendered without a fight. The French took 60 cannons and a lot of ammunition. French troops stayed in Navarino. They rebuilt the forts and houses. They also set up a hospital.

Methoni is Taken

On October 7, General Antoine Simon Durrieu's troops arrived at Methoni. This city was well-fortified. It had 1,078 defenders and 100 cannons. Two ships blocked the port. The commanders of Methoni gave the same answer as Navarino. They said they could not surrender without the Sultan's orders. But they also knew they could not resist. So, the French took the fort. General Maison set up his headquarters in Methoni.

Koroni Surrenders

Taking Koroni was harder. General Tiburce Sébastiani arrived on October 7. He told them Navarino and Methoni had fallen. The commander refused to surrender. French engineers tried to break in but were pushed back. A dozen men were hurt. The French soldiers were angry and wanted to attack. But the general stopped them. French and British ships helped. The Ottoman commander then surrendered. On October 9, the French entered Koroni. They took 80 cannons and supplies. The fortress was then given to Greek troops.

Patras Captured

Patras was controlled by Ibrahim Pasha's troops. General Antoine Virgile Schneider's brigade went by sea to take the city. They landed on October 4. General Schneider gave the Pasha of Patras 24 hours to surrender. On October 5, the Pasha signed the surrender. But the local leaders of the Castle of Morea refused to obey. They called their pasha a traitor.

On October 14, a ship left for France. It carried news to King Charles X. The news was that Navarino, Methoni, Koroni, and Patras had surrendered. Only the Castle of Morea was still held by the Turks.

Siege of the Castle of Morea

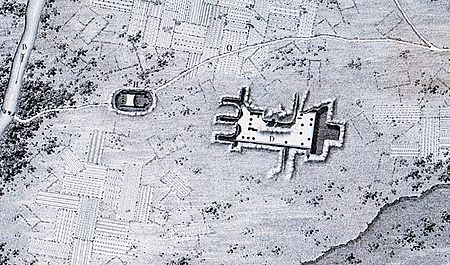

The Castle of the Morea was built in 1499. It is near Rion, north of Patras. It guarded the entrance to the Gulf of Corinth.

General Schneider tried to negotiate with the leaders. But they refused and even shot at him. So, the French began a siege. They used cannons to attack the walls. General Maison sent more troops and artillery. These reinforcements arrived on October 26. New powerful batteries were set up. They were named after kings and dukes. French and British ships also joined the attack.

On October 30, the cannons opened fire. In four hours, a large hole was made in the walls. The leaders then offered to surrender. General Maison said they had to leave the fort without weapons or belongings. The leaders surrendered. The battle cost the French 25 soldiers killed or wounded.

What the Military Expedition Achieved

By November 5, 1828, all Turks and Egyptians had left Morea. About 26,000 to 27,000 people were forced to leave. The French army had captured all the forts in just one month. General Maison said: "Our operations were successful. We did not gain military glory, but we freed Greece. Morea is now clear of its enemies."

The French and British ambassadors met in September 1828. They wanted to negotiate Greece's status. General Maison suggested extending military operations to other parts of Greece. France supported this idea. But the British Prime Minister, the Duke of Wellington, disagreed. He wanted Greece to be limited to the Peloponnese. So, the Greeks had to fight for other territories themselves. The French army would only help if the Greeks were in trouble.

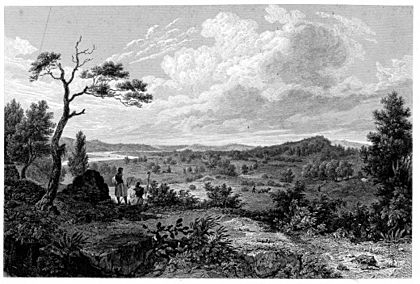

The Ottoman Empire could no longer rely on Egyptian troops. The situation was like before 1825. The Greek rebels had been winning then. After the French expedition, the new Hellenic Armed Forces only had to fight Turkish troops in Central Greece. The Greeks won several battles. The Battle of Petra in September 1829 was important. It was the first time Greeks fought and won as a regular army. This was the last battle of the Greek War of Independence.

However, Greece's independence was only fully recognized later. This happened after Russia won the Russo-Turkish War of 1828–29. The Treaty of Adrianople and Treaty of Constantinople confirmed Greece's independence in 1832. The new Kingdom of Greece included the Peloponnese, some islands, and central Greece.

French Presence in the Peloponnese

French troops began leaving Greece in January 1829. General Maison and General Durrieu left in May 1829. Only one brigade of 5,000 men stayed. This "occupation" brigade was led by General Antoine Virgile Schneider. They were stationed in Navarino, Methoni, and Patras. Fresh troops arrived from France to replace them. The French troops stayed for almost five years. They were led by General Maison (1828–1829), then General Schneider (1829–1831), and finally General Guéhéneuc (1831–1833).

During their stay, the French troops built many things. They raised fortifications and built barracks. They constructed bridges, like those over the Pamissos River. They built the first road in independent Greece, from Navarino to Methoni. Hospitals were set up in Navarino, Modon, and Patras. Health teams helped the Greek people. For example, they helped control a plague epidemic in 1828.

Many improvements were made in Peloponnesian cities. These included schools, postal services, and printing companies. Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Victor Audoy designed the first urban plans for modern Greece. He built new cities like Modon (now Methoni) and Navarino (now Pylos). These cities were designed like French towns. They had central squares with covered walkways. He also built the famous Capodistrian School in Methoni. These cities quickly grew and became active again.

The Governor of Greece, Ioannis Kapodistrias, asked France for help. He wanted French army officers to organize the new Greek army. French captains like Stamatis Voulgaris and Auguste-Théodore Garnot were sent. They designed urban plans for several Greek cities. Garnot also started the first military engineering corps in 1828. Captain Pauzié founded the Hellenic Central Military Academy in 1828. This school was based on a French model. Captain Pierre Peytier created the first accurate map of the new Greek state in 1832.

The French troops left Greece in August 1833. This was shortly after King Otto of Greece arrived. Bavarian soldiers and officers replaced them.

The Cost in Lives

Even though there were few battles, many French soldiers died. Between September 1828 and April 1829, 4,766 soldiers got sick. About 1,000 died. This was reported by Dr. Gaspard Roux, the Chief Medical Officer.

Almost a third of the French troops suffered from fevers, diarrhea, and dysentery. These diseases were common in the marshy areas where they camped. The epidemic peaked in October 1828. It was likely malaria, a disease common in the region at that time. Malaria was finally wiped out in Greece in 1974.

Doctors knew that swamps caused the disease. But they did not know about the Plasmodium parasite until 1880. They also did not know that Anopheles mosquitoes spread malaria until 1897.

The doctors thought the disease was caused by bad air from swamps. They also blamed temperature changes, hard work, and bad food and water. Cooler winter weather helped. Moving soldiers into barracks and improving hygiene also reduced deaths. Medicines like quinine also helped.

The total number of deaths reached about 1,500 by 1833. Some died from accidents, like a gunpowder explosion in Navarino. Others died in small conflicts. The scientific mission also suffered from malaria in 1829.

Today, there are memorials for these French soldiers. You can see them in places like Sphacteria islet, Gialova, Kalamata, and Nafplio.

The Scientific Expedition

Starting the Scientific Mission

The Morea expedition was France's second major military-scientific mission. The first was in Egypt in 1798. The last was in Algeria in 1839. All these expeditions were started by the French government. Scientists worked closely with the army. The Egypt expedition set a model for future scientific work. Since Greece was also an important ancient region, a similar mission was planned.

The French Interior Minister asked six experts from the Institut de France to choose the scientists. Jean-Baptiste Bory de Saint-Vincent was chosen to lead the mission in December 1828. The experts also decided where the scientists would go and what they would study. Bory was told to study not just plants and animals, but also places and people.

The expedition had nineteen scientists. It was divided into three groups: Physical Sciences, Archaeology, and Architecture-Sculpture. Bory de Saint-Vincent led the Physical Sciences group. Léon-Jean-Joseph Dubois led Archaeology. Guillaume-Abel Blouet led Architecture and Sculpture. The painter Amaury-Duval drew portraits of these leaders.

The scientists left Toulon on February 10, 1829. They arrived in Navarino on March 3, 1829. The army provided support like tents and tools.

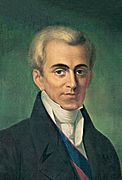

Soon after the scientists arrived, Governor Ioannis Kapodistrias met them. He also met with Edgar Quinet, a historian. Quinet later wrote about his impressions of Kapodistrias and Greek heroes like Theodoros Kolokotronis. A big dinner was held in Modon. Many important Greek and French leaders attended. Bory de Saint-Vincent introduced his team to the president. They discussed important matters. The painter Amaury-Duval noted the president's dedication to building schools. The meetings showed mutual respect between the scientists and Greek leaders.

-

The Greek President Ioannis Kapodistrias (Athens National Museum)

-

Theodoros Kolokotronis (by captain de Vaudrimey)

Physical Sciences Section

This section studied several sciences. It included botany (Jean Baptiste Bory de Saint-Vincent, Louis Despreaux Saint-Sauveur) and zoology (Gaspard-Auguste Brullé, Gabriel Bibron). It also included geography (Pierre Peytier, Pierre M. Lapie) and geology (Pierre Théodore Virlet d’Aoust, Émile Puillon Boblaye).

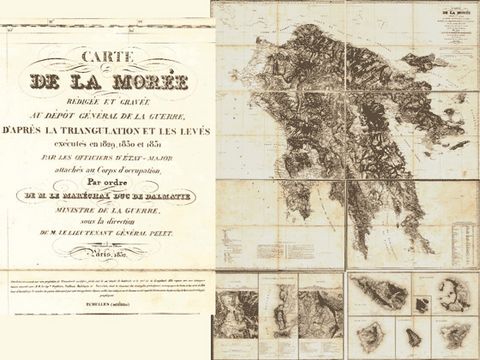

Mapping Greece

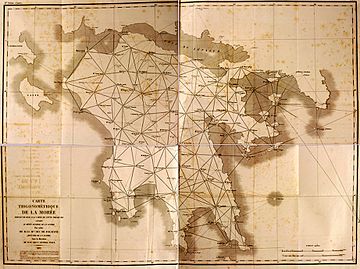

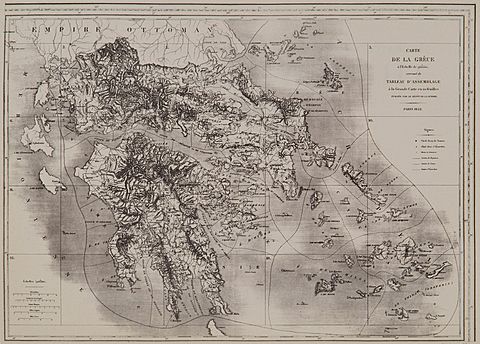

One main goal was to create accurate maps of the Peloponnese. These maps were for science, but also for business and military use. The Minister of War said that all old maps of Greece were imperfect. New, accurate maps were needed. This would help geography, trade, and military forces.

Captain Pierre Peytier was a mapmaker in the French army. Governor Ioannis Kapodistrias had invited him to Greece earlier. Kapodistrias wanted him to help organize the Greek army and map Greece. Peytier and other officers were sent in May 1828. They trained young Greek mapmakers. Peytier was also supposed to draw plans for Corinth and the Peloponnese. He joined the scientific expedition when it arrived in March 1829.

In March, a 3,500-meter base line was measured in the Argolis region. This was the starting point for all map-making measurements. Peytier and Puillon-Boblaye checked these measurements carefully. They set up 134 measuring stations on mountains and islands. They drew triangles to map the land. Peytier stayed in Greece until 1831 to finish the map.

The Map of 1832 was very precise. It was the first map of Greece made using scientific methods. It showed the exact shape of the land, rivers, and mountains. It also showed where people lived and how many there were. This map helped define the new independent Greece.

After Kapodistrias was killed in 1831, civil war made mapping difficult. King Otto I asked France to continue mapping the whole kingdom. Peytier returned to Greece in 1833 and stayed until 1836. He led most of the work for the complete map. This Map of 1852 was published under Peytier's direction. It remained the only map covering all of Greece until after 1945.

Peytier also created an album of his drawings. These showed city views, monuments, costumes, and people. His artistic style was very accurate, like a mapmaker's.

Governor Kapodistrias also asked Pierre Théodore Virlet d'Aoust to see if a canal could be dug. This canal would connect the Gulf of Corinth to the Aegean Sea. It would save ships a long and dangerous journey around the Peloponnese. Virlet d'Aoust estimated the cost at 40 million gold francs. This was too expensive for Greece at the time. The canal was finally opened in 1893.

Plants and Animals

Jean Baptiste Bory de Saint-Vincent led the scientific expedition. He made detailed observations of plants. His book Flore de Morée (1832) listed 1,550 plants. Many of these had not been described before. He collected the plants in Greece. Then, he classified and described them back in Paris. Other famous botanists helped him.

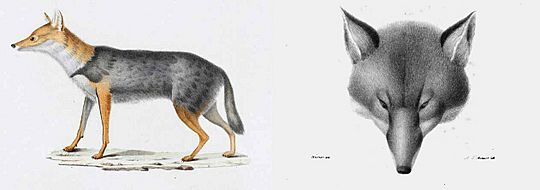

In zoology, few new animal species were found. However, the expedition identified the jackal species in the region for the first time. This specific type of jackal was unique to the area. Bory de Saint-Vincent named it the Morea jackal (Canis aureus moreoticus). He brought back skins and a skull to Paris.

Bory was joined by other scientists. These included zoologists, entomologists, and geologists. The painter Prosper Baccuet also came along. He drew the landscapes, which were later published.

Archaeology Section

This section was supervised by Charles-Benoît Hase and Desiré-Raoul Rochette. It included archaeologists Léon-Jean-Joseph Dubois (director) and Charles Lenormant. The historian Edgar Quinet and painters Eugène-Emmanuel Amaury-Duval and Pierre Félix Trézel were also part of it. A Greek writer, Michel Schinas, joined them.

Their job was to find 80 ancient sites. They used old writings, like those by Pausanias. They had to map the sites accurately. Then, with the architecture section, they would draw plans and start digging. They also planned to buy old manuscripts from monasteries.

The archaeology section faced many challenges. Its members got sick and argued. Charles Lenormant and Edgar Quinet decided to work alone. Quinet visited Athens and other islands. He got sick and returned to France in June. His book Grèce moderne et ses rapports avec l’Antiquité was published in 1831. The sculptor Jean-Baptiste Vietty also traveled alone. He continued his research in Greece until 1831.

Because of these problems, the archaeology section did not complete its original plan. Most of the archaeological work was done by the Architecture and Sculpture section.

Architecture and Sculpture Section

This section was led by the architect Guillaume-Abel Blouet. He was assisted by archaeologist Amable Ravoisié and painters Frédéric de Gournay and Pierre Achille Poirot. Later, Léon-Jean-Joseph Dubois and painters Pierre Félix Trézel and Amaury-Duval joined them.

The architect Jean-Nicolas Huyot gave very clear instructions. The team had to keep a detailed diary of their digs. They needed to record measurements, draw maps, and describe the land.

Travel and Discoveries

The published works described the routes taken and the monuments found. Volume I of Expédition de Morée. Section des Beaux Arts described Navarino, Methoni, and Koroni. It included drawings of fountains, churches, and fortresses.

The landscapes were often shown as beautiful and peaceful. French soldiers and Greek shepherds were often shown together. The book described the Greeks' kindness and simple life.

The expedition visited many ancient sites. These included Pylos, Methoni, Koroni, Messene, and Olympia. They also went to Bassae, Sparta, Mycenae, and Athens.

Finding Ancient Pylos

The archaeologists used old texts to find sites. For example, they used descriptions from Homer to find the city of King Nestor, Pylos. Homer described it as "inaccessible" and "sandy." This helped them find the site near Navarino. Blouet said: "These Greek buildings, which no modern traveler had mentioned, were an important discovery for us."

Digging at Ancient Messene

After visiting Navarino, Methoni, and Koroni, the team went to Messene. This ancient city was founded in 369 BC. They stayed there for a month. They were the first archaeologists to dig scientifically at this site.

They found the famous fortified walls of Messene. There were two large gates. One had a huge stone over the entrance, which Blouet called "perhaps the most beautiful in all of Greece." They mapped the site and started digging. They found parts of stadium seats, columns, altars, and sculptures. These digs helped them draw plans of the monuments. They could then create models of the stadium and its heroon.

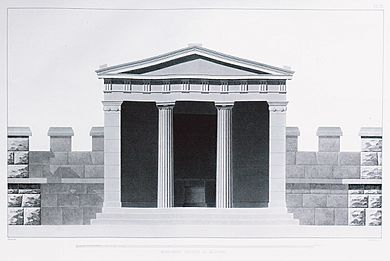

Discovering the Temple of Olympian Zeus

The expedition then spent six weeks in Olympia. Léon-Jean-Joseph Dubois and Guillaume-Abel Blouet led the first excavations. They had over a hundred workers. The site had been found in 1766, but most buildings were hidden under dirt.

Only a large piece of a column was visible. Locals had dug trenches there to remove stone. But no one knew for sure it belonged to the Temple of Olympian Zeus. Blouet explained: "The discovery was to find proof that this monument was the famous temple of Olympian Jupiter. And this is what our excavations showed." Dubois started digging at the front of the temple, and Blouet at the back. The painter Amaury-Duval wrote about how they identified the temple.

Old descriptions by Pausanias were very important. He had described the sculptures and parts of the temple. These sculptures showed the Twelve Labours of Heracles. They were new and natural-looking.

The archaeologists divided the site into squares. They dug trenches and made plans for restoring the monuments. This made archaeology more scientific. The expedition did not loot or smuggle artifacts. Blouet refused to damage monuments. Three metopes from the temple were moved to the Louvre Museum. This was done with permission from the Greek government. Many other valuable finds were re-buried to protect them.

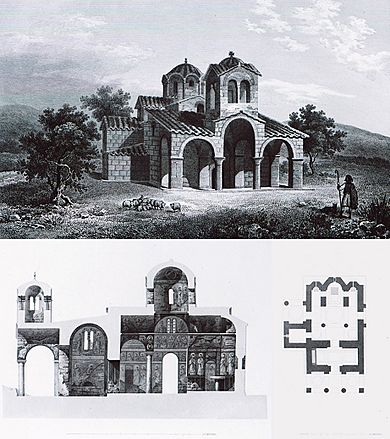

Studying Byzantine Greece

The French also studied Byzantine monuments. Before this, travelers usually only cared about ancient Greece. Medieval and modern Greece were often ignored. Blouet's book, Expedition scientifique de Morée, described many churches. These included churches in Navarino, Modon, and Samari.

Creating the French School at Athens

The scientific expedition showed the need for a permanent research center. This led to the creation of the French School at Athens in 1846. This school allowed the work started by the Morea expedition to continue.

End of the Scientific Mission

Most scientists got sick with fevers during their time in Morea. Many had to leave Greece before 1830.

The mapmaking team was hit hard. Out of eighteen officers, three died. Ten others had their health ruined and had to retire. Captain Peytier wrote that mapping in the mountains ruined his health. They had to work only in the cool season.

Jean-Baptiste Bory de Saint-Vincent wrote about the heat. He said the mapmakers got sick from working in the sun. One officer died. Émile Puillon Boblaye said two officers died and all got sick.

The physical sciences group also suffered. They forgot to use mosquito nets. They were bitten by a mosquito species that Gaspard Auguste Brullé later described. Many got violent fevers. Bory de Saint-Vincent, who was spared, went for help. A doctor saved most of them, but two people died. The Greek president provided a steamship to take them back to France.

Only Jean-Baptiste Vietty and Pierre Peytier continued their research in Greece for a longer time.

Publications of the Morea Expedition

After returning to France, soldiers and scientists wrote about their experiences. They also published their scientific findings.

Military Expedition Books

- Charles-Joseph Bastide, Considerations on the diseases that reigned in Morea, during the campaign of 1828 (Internet Archive).

- Alexandre Duheaume, Souvenirs of Morea, to serve the history of the French expedition in 1828-1829. (Gallica - BnF).

- Jacques Mangeart, Souvenirs of Morea: collected during the stay of the French in Peloponnese (Google books).

- Gaspard Roux, Medical history of the French army in Morea, during the campaign of 1828 (Google books).

Scientific Expedition Books

Physical Sciences Section

The scientists published their results in six books. These were grouped into three volumes and an Atlas. They were called "The scientific expedition of Morea. Section of Physical Sciences".

- Volume I: Relation (1836) by Bory de Saint-Vincent.

- Volume II: First Part: Geography and Geology (1834) by Bory de Saint-Vincent.

- Volume III: Second Part: Botany (1832) by Fauché, Adolphe Brongniart, Chaubard, Bory de Saint-Vincent.

- Atlas (1835): Maps, Landscapes, Geology, Zoology, Botany.

Other works included:

- New Flora of Peloponnese and Cyclades by Bory de Saint-Vincent (1838).

- Geographical Research on the Ruins of Morea by Émile Puillon Boblaye (1836).

- The Peytier Album, Liberated Greece and the Morea Scientific Expedition (1971).

Archaeology Section

- On Modern Greece, and its relations with antiquity by Edgar Quinet (1830).

- Souvenirs (1829-1830) by Eugène Emmanuel Amaury Duval (1885).

Architecture and Sculpture Section

- Volume I: Scientific Expedition of Morea ordered by the French Government; Architecture, Sculptures, Inscriptions and Views of Peloponnese, Cyclades and Attica (1831) by Abel Blouet and others.

- Volume II: Scientific Expedition of Morea... (1833) by Abel Blouet and others.

- Volume III: Scientific Expedition of Morea... (1838) by Abel Blouet and others.

Images for kids

| Precious Adams |

| Lauren Anderson |

| Janet Collins |