Christian Wolff (philosopher) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Christian Wolff

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 24 January 1679 |

| Died | 9 April 1754 (aged 75) |

| Education | University of Jena (1699–1702) University of Leipzig (Dr. phil. habil., 1703) |

| Era | 18th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Age of Enlightenment Rationalism |

| Institutions | Leipzig University University of Halle University of Marburg |

| Thesis | Philosophia practica universalis, methodo mathematica conscripta (On Universal Practical Philosophy, Composed from the Mathematical Method) (1703) |

| Academic advisors | Ehrenfried Walther von Tschirnhaus Gottfried Leibniz (epistolary correspondent) |

| Notable students | Mikhail Lomonosov A. G. Baumgarten |

|

Main interests

|

Philosophical logic, metaphysics |

|

Notable ideas

|

Theoretical philosophy has for its parts ontology (also philosophia prima or general metaphysics) and three special metaphysical disciplines (rational psychology, rational cosmology, rational theology) Coining the philosophical term "idealism" |

|

Influenced

|

|

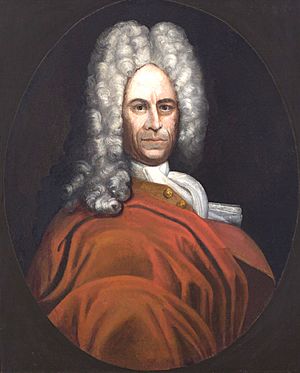

Christian Wolff (born January 24, 1679 – died April 9, 1754) was an important German philosopher. He is known as one of the most famous German thinkers between Leibniz and Kant. Wolff's work covered many subjects of his time. He used a special mathematical way of thinking to explain his ideas. This method showed the peak of Enlightenment rationality in Germany.

Wolff followed Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz by writing his scholarly works mainly in German. However, he also translated them into Latin so people across Europe could read them. He helped start new fields like economics and public administration as subjects taught at universities. He often gave advice to government officials and believed that university education should prepare people for professional careers.

Contents

Life of Christian Wolff

Christian Wolff was born in Breslau, Silesia (now Wrocław, Poland). His family was not wealthy. He first studied mathematics and physics at the University of Jena. Soon after, he also began studying philosophy.

In 1703, he became a private lecturer at Leipzig University. He taught there until 1706. Then, he became a professor of mathematics and natural philosophy at the University of Halle. Around this time, he met Gottfried Leibniz through letters. Wolff's own philosophical system was a changed version of Leibniz's ideas.

At Halle, Wolff first taught only mathematics. But when a colleague left, he started teaching physics. Soon, he was teaching all the main areas of philosophy.

Wolff's Conflict with Pietists

Wolff's ideas about philosophical reason seemed to go against the religious beliefs of some of his colleagues. Halle was a center for a religious group called Pietism. This group had become very strict in its own way. Wolff wanted to base religious truths on ideas that were as certain as mathematical proofs.

A big conflict started in 1721. Wolff gave a speech called "On the Practical Philosophy of the Chinese." In this speech, he praised the good moral ideas of Confucius. He suggested that human reason could find moral truth on its own.

On July 12, 1723, Wolff gave another lecture. He compared Moses, Christ, and Mohammed with Confucius. He based his ideas on books by missionaries.

A professor named August Hermann Francke accused Wolff of believing in fatalism and atheism. Fatalism is the idea that everything is already decided and cannot be changed. Because of these accusations, Wolff was removed from his job at Halle in 1723. This was a very famous academic event in the 18th century.

The king, Frederick William I, was told that if Wolff's ideas were true, soldiers who ran away could not be punished. This was because their actions would have been "predetermined." The king became very angry. He immediately fired Wolff and ordered him to leave Prussian land within 48 hours.

Life After Halle

Wolff left for Saxony the same day. He then went to Marburg, where he had already been offered a job at the University of Marburg. The ruler of Hesse welcomed him warmly. His expulsion made his philosophy famous everywhere. People discussed his ideas widely, and many books were written for or against them.

Historian Jonathan I. Israel said this conflict was one of the most important cultural clashes of the 18th century.

Crown Prince Frederick, who would later become Frederick the Great, defended Wolff. He ordered one of Wolff's former students to translate one of Wolff's books into French. Frederick also suggested sending a copy of Wolff's Logique to Voltaire.

In 1738, King Frederick William tried to read Wolff's work. In 1740, Frederick William died. One of the first things his son, Frederick the Great, did was to invite Wolff back to Prussia. Wolff refused at first, but then accepted a job at Halle on September 10, 1740.

His return to Halle on December 6, 1740, was like a victory parade. In 1743, he became the head of the university. In 1745, he was given the title of Freiherr (Baron). He was possibly the first scholar to become a Baron in the Holy Roman Empire because of his academic work.

When Wolff died on April 9, 1754, he was a very rich man. His wealth came mostly from his teaching fees, salary, and book sales. He was also a member of many important academies. His followers, called the Wolffians, were the first group of philosophers to be named after a German thinker. They were very influential in Germany until Kant's ideas became popular.

Wolff was married and had children.

Wolff's Philosophical Ideas

Wolff's philosophy always emphasized clear and organized explanations. He believed that reason could make any subject easy to understand. He was special because he wrote his books in both Latin and German. Because of his influence, subjects like natural law and philosophy were taught in most German universities.

Wolff's system kept the ideas of Leibniz about everything being determined and the world being the best possible. However, Wolff's ideas about monadology (tiny, simple substances) were less central. Instead, he saw them as either conscious beings (souls) or simple atoms. The idea of "pre-established harmony" also became less important as a deep philosophical concept. Wolff also brought back the principle of contradiction as the main rule for philosophy.

Wolff divided philosophy into two main parts: theoretical and practical. Logic, sometimes called philosophia rationalis, was the introduction to both.

Theoretical Philosophy

Theoretical philosophy included ontology or philosophia prima, which was a general metaphysics. This part came before the three special metaphysics topics: rational psychology (about the soul), rational cosmology (about the world), and rational theology (about God). These three subjects were called empirical and rational because they did not rely on religious revelation. This way of organizing philosophy is well-known because of Kant's work.

Wolff saw ontology as a science based on logic and reason. It was based on two main rules:

- The principle of non-contradiction: "It cannot happen that the same thing is and is not." This means something cannot be true and false at the same time.

- The principle of sufficient reason: "Nothing exists without a sufficient reason for why it exists rather than does not exist." This means everything has a reason for being the way it is.

Wolff believed that "beings" (things that exist) are defined by their "determinations" or "properties." These properties cannot have contradictions. There are three types of properties:

- Essentialia: These define what something is and are necessary for it to exist.

- Attributes: These follow from the essentialia and are also necessary.

- Modes: These are just accidental or temporary properties.

Wolff thought that "existence" was just one property among others. Ontology studies all beings, whether they actually exist or not. But all beings, existing or not, have a sufficient reason. For things that don't actually exist, their reason comes from their essential nature. Wolff called this a "reason of being." He contrasted it with a "reason of becoming," which explains why some things actually exist.

Practical Philosophy

Practical philosophy was divided into ethics, economics, and politics. Wolff's main moral idea was to achieve human perfection. He saw this realistically as the kind of perfection people could actually reach in the real world. This mix of Enlightenment hope and practical thinking made Wolff very successful. It also made him popular as a teacher for future leaders and business people.

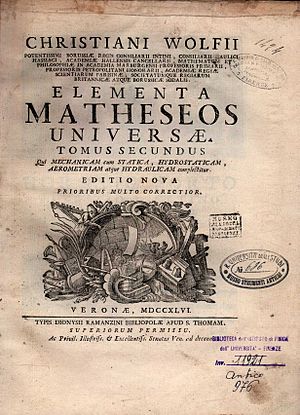

Wolff's Important Books

Here are some of Wolff's most important works:

- Dissertatio algebraica de algorithmo infinitesimali differentiali (A Dissertation on the Algebra of Solving Differential Equations Using Infinitesimals; 1704)

- Anfangsgründe aller mathematischen Wissenschaften (Foundations of All Mathematical Sciences; 1710)

- Vernünftige Gedanken von den Kräften des menschlichen Verstandes (Reasonable Thoughts on the Powers of the Human Understanding; 1712)

- Vern. Ged. von Gott, der Welt und der Seele des Menschen, auch allen Dingen überhaupt (Reasonable Thoughts on God, the World, and the Human Soul, and All Things in General; 1719)

- Philosophia rationalis, sive logica (Rational Philosophy, or Logic; 1728)

- Philosophia prima, sive Ontologia (First Philosophy, or Ontology; 1730)

- Cosmologia generalis (General Cosmology; 1731)

- Psychologia empirica (Empirical Psychology; 1732)

- Psychologia rationalis (Rational Psychology; 1734)

- Theologia naturalis (Natural Theology; 1736–1737)

- Jus Gentium Methodo Scientifica Pertractum (The Law of Nations According to the Scientific Method; 1749)

See also

In Spanish: Christian Wolff para niños

In Spanish: Christian Wolff para niños

- Mons Wolff (a mountain on the Moon named after him)

- Wawrzyniec Mitzler de Kolof (a student of Wolff)

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |