History of Silesia facts for kids

Silesia is a region in Central Europe with a long and interesting history. For thousands of years, different groups of people have lived here, and the land has been part of many different countries. Imagine a place that has seen ancient tribes, powerful kingdoms, and big empires come and go! This article will tell you about the journey of Silesia, from its earliest inhabitants to how it looks today. You'll learn about the cultures that shaped it, the wars that changed its borders, and the people who called it home.

In the second half of the 2nd millennium BC, during the late Bronze Age, Silesia was home to the Lusatian culture. Around 500 BC, people called Scyths arrived, followed by Celts in the southern and southwestern parts. Later, in the 1st century BC, Germanic tribes like the Silingi settled here.

Around the 6th century AD, Slavs began to move into the area. The first known states in Silesia were Greater Moravia and Bohemia. In the 10th century, a Polish ruler named Mieszko I made Silesia part of the Polish state. It stayed with Poland until the country began to break into smaller parts. After that, Silesia was divided among different dukes from the Piast dynasty, who were descendants of Władysław II the Exile.

During the Middle Ages, Silesia was split into many small areas called duchies, each ruled by a duke from the Piast family. At this time, more and more German people moved into the region from the Holy Roman Empire. This was because the economy was growing, and new towns were being built under German town law. This led to a big increase in German culture and influence.

Between 1289 and 1292, the Bohemian king Wenceslaus II became the ruler over some of the Upper Silesian duchies. In the 14th century, Silesia became part of the Crown of Bohemia under the Holy Roman Empire. Later, in 1526, it passed to the Habsburg monarchy. However, one small part, the Duchy of Crossen, became part of Margraviate of Brandenburg in 1476.

In 1742, most of Silesia was taken by King Frederick the Great of Prussia during the War of the Austrian Succession. It then became the Prussian Province of Silesia.

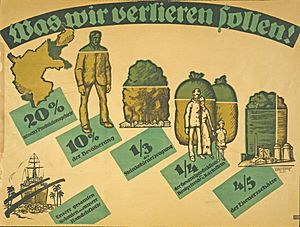

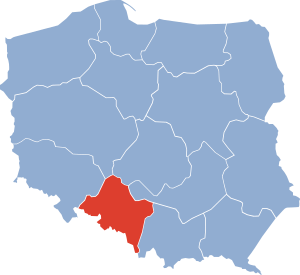

After World War I, Silesia was divided. Lower Silesia, which had mostly German people, stayed with Germany. Upper Silesia, after some uprisings by Polish people, was split. Part of it joined the Second Polish Republic and became the Silesian Voivodeship. The German part of Silesia was divided into two provinces: Lower Silesia and Upper Silesia. The small part of Silesia that Austria kept after the Silesian Wars became part of the new country of Czechoslovakia. During Second World War, Nazi Germany invaded the Polish parts of Upper Silesia.

In 1945, both provinces were taken over by the Soviet Union. According to the Potsdam Agreement, most of this land was given to the Polish People's Republic. Many German people who lived there either fled or were forced to leave. Polish people who had been forced out of their homes in eastern Poland then moved into Silesia.

Contents

- Ancient Times: Early People and Cultures

- Ancient History: Written Records Begin

- Early Medieval Slavic Tribes

- Great Moravia and Bohemia's Influence

- Kingdom of Poland: A New Chapter

- Silesian Duchies: A Divided Land

- Kingdom of Bohemia: New Overlords

- Habsburg Monarchy: Religious Changes

- Kingdom of Prussia: A New Power

- German and Austro-Hungarian Empires

- Interwar Period and World War II

- Poland, Czech Republic, and Germany: After the War

- Images for kids

- See also

Ancient Times: Early People and Cultures

The first signs of humans in Silesia are from a very long time ago, between 230,000 and 100,000 years ago. Modern humans arrived about 35,000 years ago. Over time, different archaeological cultures lived in Silesia during the Stone Age, Bronze Age, and Iron Age.

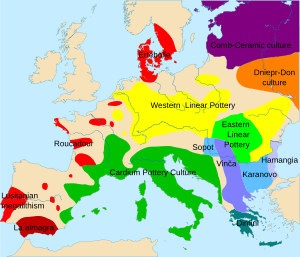

In the late Bronze Age, the Lusatian culture covered Silesia. Later, the Scythians and Celts were important in the region. Even later, Germanic tribes moved to Silesia, possibly from northern Germany or Scandinavia.

Celts in Silesia (4th-1st centuries BC)

The Celts came to parts of Silesia in at least two waves. The first group arrived around the beginning of the 4th century BC. They were part of the La Tène culture. Archaeologists have found proof of Celtic presence south of modern Wrocław, and on the Głubczyce Plateau, where many Celtic coins were found. One of the largest Celtic settlements in Silesia was found at Nowa Cerekwia.

Celtic culture in Silesia was strong during the 4th, 3rd, and most of the 2nd centuries BC. But by the end of the 2nd century BC, the population dropped sharply, and some Celtic areas became empty. This happened around the time the Cimbri and Teutones tribes moved through Silesia. After the 1st century AD, there is no more evidence of Celtic culture in Silesia. The Przeworsk culture then took its place.

Ancient History: Written Records Begin

The first written records about Silesia come from ancient writers like the Egyptian Ptolemy and the Roman Tacitus. According to Tacitus, in the 1st century AD, Silesia was home to many different groups, led by the Lugii. The Silingi, likely a Germanic tribe, were also part of this group. Other Germanic tribes lived in the region too.

After about AD 500, during the Migration Period, most of the Germanic tribes left Silesia and moved to Southern Europe. At the same time, Slavic tribes began to arrive and spread throughout Silesian lands.

Early Medieval Slavic Tribes

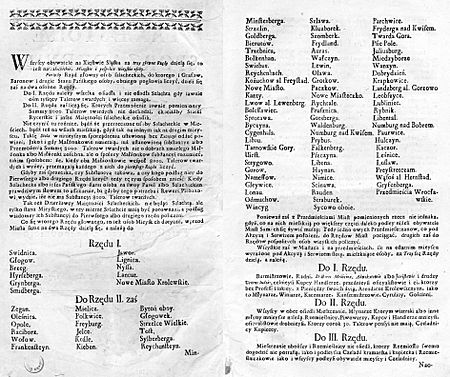

Records from the 9th and 10th centuries show that the area that became Silesia was inhabited by several Slavic tribes. These tribes had Latinized names in the old writings:

- The Sleenzane (Ślężanie) lived near modern Wrocław and the Ślęza river. They probably had about 60,000 to 75,000 people and were divided into 15 "cities" or groups.

- The Opolini (Opolanie) lived near modern Opole. They had about 30,000 to 40,000 people and 20 groups.

- The Dadodesani (Dziadoszanie) lived near modern Głogów, with about 30,000 people and 20 groups.

- The Golensizi (Golęszyce) lived near Racibórz, Cieszyn, and Opawa. They had five groups.

- The Lupiglaa (Głubczyce) probably lived on the Głubczyce Plateau, near Głubczyce, and had 30 groups.

- The Trebouane (Trzebowianie) lived near modern Legnica and might have had 25,000 to 30,000 people.

- The Poborane (Bobrzanie) lived along the Bóbr river.

- The Psyovians (Pszowianie) lived near Pszów.

Around the year 1000, the total population of Silesia is thought to have been about 250,000 people.

Great Moravia and Bohemia's Influence

In the 9th century, parts of Silesia came under the influence of Great Moravia, which was the first known state in the region. After Great Moravia declined, Bohemia slowly took control of Silesia. In the early 10th century, Vratislaus I conquered the Golensize tribe and soon after took Middle Silesia. The city of Wrocław might have been founded by him. His son, Boleslaus I, later conquered other tribes. Bohemian rulers also tried to bring Christianity to the region and opened Silesia up for international trade.

Kingdom of Poland: A New Chapter

By the end of the 9th century, Silesia was influenced by two powerful neighbors: the Holy Roman Empire and Poland. In 971, the Holy Roman Emperor Otto I tried to spread Christianity in Silesia. However, the expanding Polish state under Mieszko I conquered Silesia around the same time. In 990, during a war with Bohemia, Mieszko took Middle Silesia. Mieszko's successor, Bolesław I, created an independent Polish church region in 1000, with a bishopric in Wrocław.

After Bolesław I died in 1025, his son Mieszko II became king of Poland. But due to invasions and a pagan revolt, he had to go into exile. He later regained power but died in 1034. His son, Casimir the Restorer, faced more revolts and had to flee. A Bohemian Duke, Bretislaus I, took control of Silesia in 1038. Casimir returned to Poland in 1039 and slowly reunited the country. In 1050, he took back most of Silesia but had to pay a yearly tribute to Bohemia. This tribute often led to wars between the two countries.

Internal conflicts also troubled Silesia. In 1093, Silesian nobles revolted. This period of wars and unrest ended with a peace treaty in 1137, which set the border between Bohemia and Silesia.

In 1146, High Duke Władysław II was forced out of Poland by his brothers. Silesia then became part of the new High Duke's lands. In 1163, Władysław's three sons took control of Silesia with support from the Holy Roman Empire. They divided the territory among themselves in 1172. This division led to the special position of what would become Upper Silesia. In 1202, Silesia's duchies became independent under their own laws.

In the early 13th century, a Silesian duke named Henry I reunited much of the divided Kingdom of Poland. He became the duke of Kraków in 1232, which made him the senior duke of Poland. He also gained control of most of Greater Poland. Henry tried to become king of Poland but didn't succeed. His son, Henry II the Pious, continued his work until his sudden death in 1241 at the Battle of Legnica. After his death, his successors couldn't keep the lands outside Silesia, which were lost to other Piast dukes. Historians call the lands controlled by Silesian dukes during this time the "Monarchy of the Silesian Henries." Back then, Wrocław was the political center of the divided Kingdom of Poland.

Mongol Invasion

In 1241, after attacking Lesser Poland, the Mongols invaded Silesia. This caused widespread panic and many people fled. They looted much of the region but failed to capture the castle of Wrocław. They then defeated the combined Polish and German forces under Henry II at the Battle of Legnica. After the death of their leader, Ögedei Khan, the Mongols decided not to go further into Europe and returned east.

German Settlement

The German settlement in Silesia, called Ostsiedlung, began in the late 12th century and really took off in the early 13th century. The ruling Piast dukes encouraged this to develop their lands and increase their power. Silesia was not very populated at the time, with about 150,000 people. Settlements were small villages.

German monks, who came with Duke Bolesław I, helped start this settlement. They were allowed to settle Germans on their lands, and these new settlements used German law instead of Polish law. This became a model for other German settlements. Towns were given special charters under German town law, like the Magdeburg law.

Duke Henry I was the first Slavic ruler outside the Holy Roman Empire to invite German settlers on a large scale. His main goal was to secure the borders. Early German settlements were built in border areas. Another goal was to use the advanced mining technologies of German miners. This led to the founding of mining towns like Goldberg in 1211 and Löwenberg in 1217. These towns had a typical layout with a central square called the Ring.

After the Mongol invasion in 1241, German settlement activities expanded greatly. By the end of the 13th century, most of Silesia was affected by this colonization. The population density, settlement types, and the people themselves changed a lot. Large, well-planned villages became common. A network of almost 130 towns covered the country.

The population of Silesia grew significantly. By 1400, it's estimated there were about 30,000 Czechs and 30,000 Germans in Upper Silesia, along with 240,000 Poles (80%). In Lower Silesia, the number of Poles and Germans was estimated to be around 375,000 for each group. After German colonization, Polish was still the main language in Upper Silesia and parts of Lower and Middle Silesia north of the Oder river. In these areas, Germans who arrived often became Polonized. Germans mostly lived in large cities, while Poles lived in rural areas.

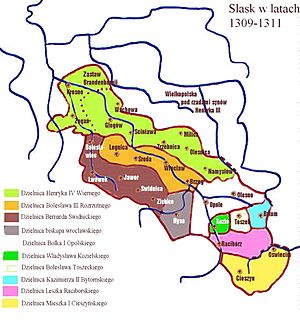

Silesian Duchies: A Divided Land

After the death of Henry II the Pious, his lands were divided among different Piast dukes. In the late 13th century, Henry II's grandson, Henryk IV Probus, tried to become king of Poland but died in 1290. Other dukes also tried to unite Poland. Meanwhile, King Wenceslaus II of Bohemia became King of Poland in 1300. The next 50 years saw many wars between Poland and a group of Bohemians, Brandenburgers, and Teutonic Knights who wanted to divide Poland.

During this time, all Silesian dukes accepted the Polish king's claim to be the main ruler over other Piasts. In 1319 and 1320, the nine dukes of Silesia declared that their lands were part of the Polish Kingdom.

The last independent Silesian Piast duke, Bolko II of Świdnica, died in 1368. After his wife died in 1392, all Silesian Piasts became vassals (meaning they owed loyalty and service) to the Bohemian Crown.

Over the next centuries, the lines of the Piast dukes of Silesia died out. Their duchies were then taken over by the Bohemian Crown. By the end of the 14th century, Silesia was split into 17 small areas called principalities. The rulers of these areas often fought among themselves, leading to a lot of disorder.

Kingdom of Bohemia: New Overlords

Even though the Pope agreed to the Polish king's coronation, his right to the crown was questioned by the Bohemian kings. In 1327, John of Bohemia invaded. Most of the Silesian dukes became dukes of Bohemia. In 1335, John of Bohemia gave up his claim to the Polish crown in exchange for the Polish king giving up his claims to Silesia. This was made official in the Treaty of Trentschin and later confirmed in the 1348 Treaty of Namslau. This made the border between the Holy Roman Empire (and German-speaking areas) and Silesia one of the longest-lasting borders in Europe.

Being connected to Bohemia helped Silesia's economy. Wrocław, a major trading center, made new connections with cities like Budapest and Venice to the south, and Toruń and Gdańsk to the north. It even became a member of the Hanseatic League, a powerful trading group. This economic growth led to a rich city culture, with important buildings and many Silesians attending universities in Kraków, Leipzig, and Prague.

After the death of Charles IV in 1378, Bohemia's protection of Silesia ended. The country became filled with conflicts and robber barons (nobles who robbed travelers) caused a lot of damage. The situation got much worse during the Hussite wars.

The burning of Jan Hus (a religious reformer) led to religious and national unrest in Bohemia. After the Bohemian king died in 1419, the Czechs refused to accept Sigismund as their new king. Sigismund then called a meeting in Wrocław to plan actions against the revolting Czechs. Silesian rulers promised to help. In 1421, a Silesian army invaded Bohemia but was defeated by the Hussites. Moravia joined the Hussite movement, and Silesia became a target for the radical Hussites. From 1427 onwards, the Hussites invaded Silesia many times, destroying over 30 towns and causing great damage. Some Silesian towns became Hussite bases for several years. The Hussite threat lasted until 1434.

Dueling Kings

After Sigismund's death in 1437, the Bohemian crown was fought over by Albert II of Habsburg and Władysław III of Poland. Silesia, located between Poland and Bohemia, became a battleground again. Most Silesian princes supported Albert's widow. After many battles, a compromise was reached: both kings kept their titles, with one ruling Bohemia and the other ruling Moravia, Lusatia, and Silesia.

Decline

Silesia's economy declined because of the Hussite wars and because trade routes avoided the region due to the danger. New trade routes also threatened Silesia's interests, leading to trade wars with Poland. The population also dropped after the late 14th century due to farming problems and the Hussite wars. Many rural settlements were abandoned, and cities lost people. This led to Germans and Slavs mixing more. The small Polish-speaking groups in Lower and Middle Silesia mostly disappeared, and these regions became largely German.

Habsburg Monarchy: Religious Changes

After King Louis II of Hungary and Bohemia died in 1526, Ferdinand I of Austria was chosen as King of Bohemia, which made him the ruler of Silesia. In 1537, a Piast Duke made an agreement for the Hohenzollern family of Brandenburg to inherit his duchy if his family line died out, but Ferdinand rejected this.

Reformation

The Protestant Reformation quickly spread in Silesia. Leaders like Frederick II of Liegnitz and George von Ansbach-Jägerndorf encouraged the new faith. The city of Breslau also adopted Protestantism. By 1564, only the bishop of Breslau, a few rulers, and about 10% of the population remained Catholic. Silesia became closely linked to the Protestant centers of Brandenburg and Saxony.

Ferdinand I and Maximilian II did not persecute Protestants, but this changed when Rudolf II became emperor. To end the oppression, the Silesian nobles joined the Bohemian Protestants and stopped paying taxes to the emperor in 1609. They forced the emperor to issue a "Letter of Majesty" that gave them more rights.

When Ferdinand II, a strong Catholic, became emperor, he began to force the Catholic faith. The Silesian nobles joined the Bohemian Revolt in 1618. However, after losing the Battle of White Mountain, they had to accept Ferdinand II as their ruler. The emperor then started the Counter-Reformation, bringing Catholic groups to Silesia.

Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War reached Silesia in 1629. The emperor sent troops to occupy the country. Protestant landlords lost their lands and were replaced by Catholic families.

In 1632, Protestant countries like Saxony, Brandenburg, and Sweden invaded Silesia, and the Silesian Protestants joined them. But when Saxony made peace in 1635, Silesia lost its ally and had to submit to the emperor again. Only a few duchies and the city of Breslau kept their religious freedom.

New conflicts between 1639 and 1648 devastated the country. Swedish and imperial troops caused great damage. Cities were destroyed by fires and diseases. Many people fled to neighboring countries like Brandenburg, Saxony, or Poland, where they could practice their faith freely.

The Peace of Westphalia ended the Thirty Years' War. Some duchies and Breslau kept religious freedom, and they were allowed to build three Protestant churches, called the Churches of Peace. In the rest of Silesia, the oppression of Protestants increased, and many churches were closed. This led to more people leaving the region. Protestant churches were built near the Silesian border so people could practice their religion.

In 1676, the Duchy of Legnica and Duchy of Brzeg came under direct Habsburg rule after the last Silesian Piast duke died, even though there was an earlier agreement for Brandenburg to inherit them.

These remaining Protestant duchies were forced back to Catholicism. However, the Swedish king Charles XII later forced the emperor to restore religious freedom in these duchies. Six more churches, called "churches of mercy," were allowed to be built.

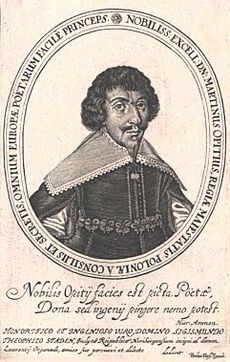

Due to the Thirty Years' War, diseases, and people leaving, Silesia lost a large part of its population. Some cities didn't recover until the 19th century. Despite the difficult times, Silesia became a center for German Baroque poetry in the 17th century.

Polish Rule Over Upper Silesia

Starting with the reign of Sigismund III Vasa (1587–1632), Polish kings became interested in Upper Silesia again. They tried to get the Duchy of Opole-Racibórz as payment for unpaid dowries. In 1637, Emperor Ferdinand III agreed to talks after France offered Poland all of Upper Silesia if Poland joined France in a war.

The situation changed when Sweden invaded Silesia. Swedish forces captured many important cities. In 1641, the Polish king Władysław IV Vasa began talks to exchange his lands in Bohemia for the Duchy of Opole-Racibórz. After heavy defeats, Ferdinand III finally agreed in 1644. The agreement in 1645 gave Władysław and his father's successors the title of Duke of Opole-Racibórz. This Polish rule brought peace to Upper Silesia and strengthened economic and cultural ties with Poland.

During the reign of John II Casimir, the king and his court lived in the Duchy after Poland was invaded by the Swedes in 1655. From Opole and Głogówek, he commanded Polish forces. He urged all Poles to rise up against the Swedes.

The king and queen tried to choose a new monarch while John was still alive. They wanted to give the Duchy of Opole-Racibórz to their candidate. But Emperor Leopold I bought the Duchy back in 1666. After the Habsburgs regained Upper Silesia, tolerance for Protestants ended, and a program to restore Catholicism began.

Kingdom of Prussia: A New Power

In 1740, King Frederick II the Great of Prussia took over Silesia. Many Silesians, especially Protestants and Germans, welcomed this. Frederick based his claim on an old treaty. His invasion in 1740 started the First Silesian War. By the end of the war, Prussia had conquered almost all of Silesia. Only a few parts in the southeast remained with Bohemia and the Austrian Habsburg monarchy. The Third Silesian War (1756–1763) confirmed Prussia's control over most of Silesia. As a result, Silesia was no longer part of the Holy Roman Empire and was ruled by Frederick as King of Prussia.

Prussia set up a modern administration in Silesia. It was divided into two regions, Breslau and Glogau, which managed 48 districts. Silesia kept a special position within Prussia.

Industry and Mining

Silesian industry suffered after the war. To help the economy, Protestant Czechs, Germans, and Poles were invited to settle, especially in Upper Silesia. Many new mine and lumber settlements were created. Frederick II supported rebuilding cities and boosting the economy, for example, by banning wool exports to Saxony or Austria.

Mining and metal production became very important in the mid-18th century. In 1769, Silesia created a standard mining law that gave miners more freedom and put them under the control of a special mining authority. At first, mining was in Lower Silesia, but it later moved to Upper Silesia.

Religious restrictions were removed early on. Many new Protestant churches were built. The Moravian Church, a Protestant group, established several new settlements. Although Frederick and the bishop of Breslau had disagreements about the Catholic Church, the king supported the Catholic school system.

Napoleonic Era

In 1806, allies of Napoleon invaded Silesia. Only a few forts held out. After reforms between 1807 and 1812, Silesia became fully part of Prussia. Catholic Church properties were taken by the state, and social and economic conditions improved. The first European university with both Protestant and Catholic departments was established in Breslau.

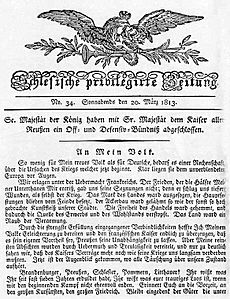

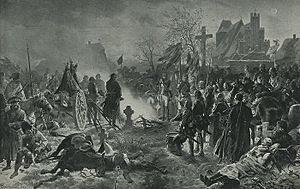

In 1813, Silesia became a center for the revolt against Napoleon. The royal family moved to Breslau, and King Frederick William III issued a letter called An mein Volk, calling the German people to fight. This war strengthened the bond between Silesians and Prussia. Silesia became one of Prussia's most loyal provinces.

In 1815, the northeastern part of Upper Lusatia was added to the province. Silesia was then divided into three government regions: Liegnitz, Breslau, and Oppeln.

Even though German dialects were widely used in Lower Silesia and some Upper Silesian cities, Polish was still the main language in Upper Silesia and parts of Lower and Middle Silesia north of the Oder river. Germans usually lived in large cities, while Poles lived mostly in rural areas. This meant Prussian authorities had to issue some official documents in Polish or both German and Polish. Over time, the Polish-speaking areas of Lower and Middle Silesia became mostly Germanized.

Uprising of the Silesian Weavers

Silesia's industry struggled after 1815. Silesian linen weavers faced problems because of Prussia's free trade policy and competition from British machines. Many weavers lost their jobs. As conditions worsened, unrest grew, leading to the Silesian cotton weavers' uprising in 1844. This uprising was watched closely by German society and inspired artists.

The recovery of Silesian industry was closely linked to railroads. The first railway line was built between Breslau and the industrial region of Upper Silesia (1842–1846). This growing network of railroads helped new companies, leading to the growth of industrial centers like Breslau, Waldenburg, and Upper Silesia. Upper Silesia became the second-biggest industrial area in Germany. The concentration of mining, metal production, and factories led to huge growth in settled areas, especially workers' villages near mines. New cities like Kattowitz and Königshütte emerged.

Silesians were unhappy with the absolute rule in Prussia, which led to a democratic revolt in 1848. Uprisings happened in Breslau and peasant revolts across the country. These efforts were put down by the Prussian state.

In the 1860s, as political parties developed, the special status of Upper Silesia began to grow due to differences in religion, language, and nationality.

German and Austro-Hungarian Empires

As a Prussian province, Silesia became part of the German Empire when Germany was united in 1871. There was a lot of industrialization in Upper Silesia, and many people moved there. Most people in Lower Silesia spoke German and were Lutheran. In areas like the District of Oppeln and rural parts of Upper Silesia, there was a larger group of Slavic-speaking Poles and Roman Catholics. In all of Silesia, about 23% of the population were ethnic Poles, mostly living around Kattowitz in southeast Upper Silesia.

At the same time, the areas of Ostrava and Karviná in Austrian Silesia became more industrialized. Many Polish-speaking people there were Lutherans, unlike the German-speaking Catholic Habsburg rulers of Austria-Hungary.

In 1900, Austrian Silesia had 680,422 people. Germans made up 44.69% of the population, Poles 33.21%, and Czechs and Slavs 22.05%. About 84% were Roman Catholics and 14% Protestants.

Interwar Period and World War II

Division After 1918

After Germany and Austria-Hungary lost World War I, the Treaty of Versailles decided that the people of Upper Silesia should vote to decide if they wanted to be part of Poland or Germany. This vote, called a plebiscite, was organized by the League of Nations in 1921. Before the vote, there were two Silesian Insurrections started by Polish people in the area.

In Cieszyn Silesia, there was an agreement to divide the land between Poland and Czechoslovakia based on ethnic groups. However, the Czechoslovak government didn't approve it. Czech troops invaded Cieszyn Silesia in January 1919. The planned plebiscite wasn't held in Cieszyn Silesia. Instead, the Spa Conference divided Cieszyn Silesia between Poland and Czechoslovakia along the current border.

At the Paris Peace Conference, there were proposals to give most of Upper Silesia to Poland. But this was not accepted, and a plebiscite was organized. After the vote, where Poland got 41% of the votes, a plan was made to divide Upper Silesia. This led to the Third Silesian Uprising. A new division plan was made in Geneva in 1922. The Polish parliament decided that the easternmost Upper Silesian areas should become an autonomous (self-governing) region within Poland, called the Silesian Voivodeship. This part of Silesia was the most developed and richest region of the new Polish state. After the division, the Polish minority in the German part of Upper Silesia faced discrimination.

The main part of Silesia that stayed in Germany was reorganized into two provinces: Upper Silesia and Lower Silesia. After the Nazis came to power, synagogues in cities like Wrocław were destroyed during Kristallnacht in 1938. In October 1938, Trans-Olza (part of Cieszyn Silesia) was taken by Poland from Czechoslovakia. Czech Silesia was later taken by Nazi Germany.

World War II

With the invasion of Poland, Nazi Germany conquered the mostly Polish parts of Upper Silesia. They also took additional lands. Between 1940 and 1944, about 50,000 Poles were forced to leave the area and were replaced by German settlers. The Germans also set up 23 camps for expelled Poles across Silesia. Many thousands of Silesians were forced to join the German army.

In 1940, Germany's Nazi government started building the Auschwitz and Groß-Rosen concentration camps. These camps used forced labor. In January 1945, the SS forced about 56,000 prisoners from the Auschwitz camps on death marches to the west.

Silesia also had prisoner-of-war camps, like Stalag Luft III, famous for its prisoner escapes.

Poland, Czech Republic, and Germany: After the War

In 1945, Silesia was captured by the Soviet Red Army. Many German people had already fled or were evacuated from Silesia, fearing the Soviets. Under the agreements at the Yalta Conference and the Potsdam Agreement in 1945, German Silesia east of the Oder and Lusatian Neisse rivers was given to Poland. Most of the remaining German population was then forced to leave.

Before the war, Silesia had over four million German inhabitants. Many died or fled. Most of those who remained were expelled after the war. Some were imprisoned in camps. Many Silesians also moved to other countries like Austria, the United States, and Australia. Over 30,000 Silesian men were sent to Soviet mines and Siberia, and most never returned.

In 1946, the territories were reorganized into new administrative regions in Poland. Silesian industry, especially in Upper Silesia, was not badly damaged during the war. This helped Poland rebuild and industrialize. Major businesses were taken over by the state. After the fall of communism in 1989, the most industrialized parts of Silesia began to decline, and the region started to move towards a more diverse economy.

The formerly German areas were largely repopulated by Poles, many of whom had been forced to leave their homes in eastern Polish areas taken by the Soviet Union. However, there is still a small German-speaking population around Opole, and some Slavic-speaking and bilingual people in Upper Silesia who consider themselves Poles or Silesian. The German-Polish Silesian minority is active in politics and has successfully pushed for the right to use the German language in public again.

In 1975, Poland introduced a new administrative division. The autonomy of the former Silesian Voivodeship was not brought back. Since 1991, the Silesian Autonomy Movement has tried to get autonomy for the region, but without success.

Since 1998, the Polish part of Silesia has been divided among the Lubusz, Lower Silesian, Opole, and Silesian Voivodeships.

German Area

After the war, part of the historical region of Lusatia, which was the westernmost part of Prussian Province of Lower Silesia, remained in Germany. Some people there still consider themselves Silesian and keep Silesian customs. They have the right to use the Lower Silesian flag and coat of arms.

Czech Area

Before the war, Czech Silesia had large German and Polish-speaking populations. After World War II, Czech Silesia returned to Czechoslovakia, and the ethnic Germans were expelled. However, a Polish minority still exists, especially in the Trans-Olza region.

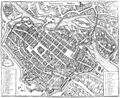

Images for kids

-

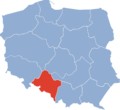

Neolithic Europe (around 4500–4000 BC): Silesia was part of the Danubian culture.

-

Władysław II the Exile, the first of the Silesian Piasts.

-

A depiction of most likely Henryk IV Probus.

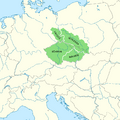

-

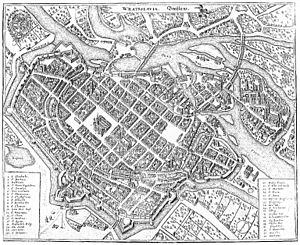

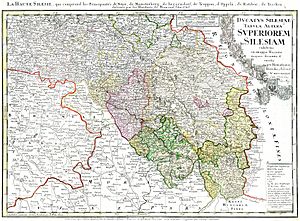

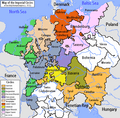

Silesia within the Holy Roman Empire of German Nation around 1512.

-

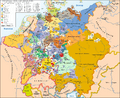

Silesia within the Holy Roman Empire under the House of Habsburg in 1648.

-

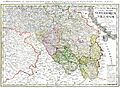

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and Duchy of Opole and Racibórz in 1648.

-

Frederick II after the Battle of Leuthen.

-

The renovated city center of Opole.

-

Aleksander Fredro monument in Wrocław's town square.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Silesia para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Silesia para niños

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |