- This page was last modified on 17 October 2025, at 10:18. Suggest an edit.

Ostsiedlung facts for kids

This page is about the medieval eastward migrations of Germans. For a general view, see History of German settlement in Central and Eastern Europe.

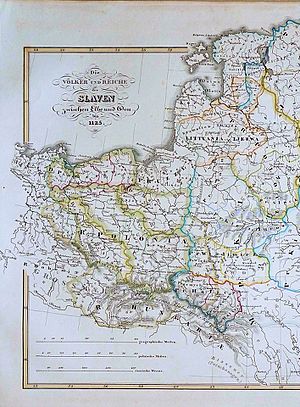

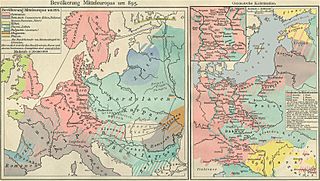

Ostsiedlung (say "Ost-zeed-loong") means "East settlement" in German. It's a term for a big movement of people from Western and Central Europe into the eastern parts of Europe during the Middle Ages. These people were mostly Germans. They moved into areas that were often sparsely populated by Slavic, Baltic, and Finnic peoples.

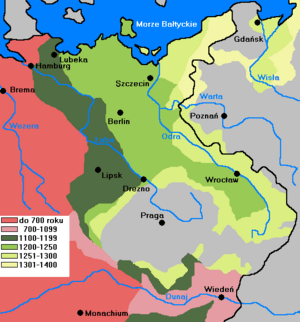

This movement happened between the 11th and 14th centuries. It changed a lot about how people lived, the laws they followed, their culture, religion, and how they farmed and traded in places like modern-day Germany (east of the Elbe River), Poland, the Czech Republic, Austria, and the Baltic countries.

Historians today see the Ostsiedlung as part of a larger European development. It was a time when societies across Europe became more organized. They improved their culture, religion, laws, government, trade, and farming methods.

Most settlers moved on their own, not as part of a big government plan. They traveled in different groups and on various paths. Many were even invited by Slavic princes and local lords who wanted to develop their lands.

Smaller groups started moving east in the early Middle Ages. Larger groups, including scholars, monks, craftspeople, and artists, followed in the mid-12th century. This movement was different from military conquests. It was about people settling down and building new communities. The Ostsiedlung ended around the early 14th century.

In the 20th century, some German nationalists, including the Nazis, used the story of Ostsiedlung to claim land and say that Germans were better than other groups. They tried to make it seem like non-German achievements in those areas were actually German. After World War II, many Germans were forced to leave these eastern lands. Their language and culture were lost in most of these areas, except for parts of Eastern Austria and Eastern Germany.

Contents

Life in Early Medieval Central Europe

During the 4th and 5th centuries, a time called the Migration Period, Germanic peoples took control of parts of the old Western Roman Empire. At the same time, Slavic peoples moved into areas in Eastern Europe and what is now Eastern Germany.

Under Carolingian Rule

Charlemagne, a powerful ruler of the Carolingian Empire, united much of Western and Central Europe in the 8th and 9th centuries. He created special border areas called "marches." Many of the later settlements happened in these marches. These areas included:

- The Danish March (against the Danes).

- The Saxon Eastern March (against the Obotrites).

- The Sorbian March (against the Sorbs).

- The Avar March (against the Avars, later the Austrian March).

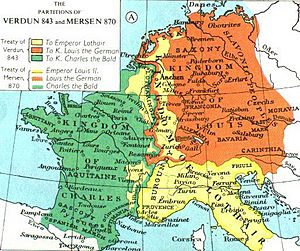

These border tribes were not always loyal to the Empire. Kings often had to fight to keep control. In 843, Charlemagne's grandsons divided the Carolingian Empire into three separate kingdoms.

East Francia and the Holy Roman Empire

Louis the German inherited the eastern lands, called East Francia. These lands became the basis for what would later be the Holy Roman Empire. The Slavic people living there, sometimes called "Wends," were often divided into many small tribes.

The kings of East Francia and the Holy Roman Empire continued to set up marches on their borders. Under Louis the German, the first groups of Catholic settlers, mainly Franks and Bavarians, moved into lands like Pannonia (modern-day Hungary, Slovakia, and Slovenia).

Over time, large areas in the northeast were conquered. Forts were built and guarded by soldiers. However, not many civilian settlers moved into these lands at first. Christian churches were set up, but a full church system only developed after German colonists arrived in the mid-12th century. Control over these conquered areas was often lost, like during the Slavic revolt of 983.

Slavic Revolt of 983

In 983, the Polabian Slavs successfully rebelled against the Holy Roman Empire's rule and Christian missions. They gained independence, but then faced internal fights and attacks from the growing Polish state, Denmark, and the Empire. This area remained under Slavic rule and was not settled by many outsiders until the 12th century.

Eastern Marches of the Holy Roman Empire

These marches were border regions that helped protect the Empire and were often places where new settlements would later grow. They included:

- The Billung March (on the Baltic Sea).

- The March of Gero (later divided into smaller marches like Brandenburg and Meissen).

- The Austrian March (in what is now Lower Austria).

- The March of Styria.

- Other smaller marches in modern-day Slovenia.

The 12th Century: A New Wave of Settlement

An early call for a crusade against the Wends in 1108, which promised new land for settlers, didn't lead to much action. But things changed later.

Holstein and Pomerania

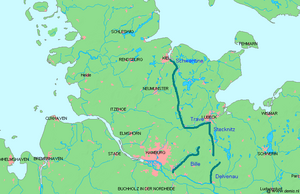

Starting in 1124, Flemish and Dutch colonists began settling south of the Eider River. In 1139, the land of the Wagri was conquered. In 1143, the city of Lübeck was founded. That same year, Count Adolf II of Schauenburg encouraged people to settle in "Eastern Holstein."

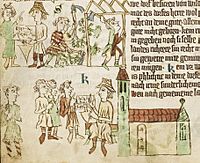

The independent Wendish lands were weakened by constant fighting. From 1119 to 1123, Pomerania took over parts of the Lutici lands. In 1124 and 1128, Duke Wartislaw I of Pomerania invited Bishop Otto of Bamberg to bring Christianity to his people. In 1147, a "Wendish Crusade" was launched to retake the lost marches.

Brandenburg and Mecklenburg

After the Wendish Crusade, Albert the Bear was able to establish and expand the Margraviate of Brandenburg in 1157. This area had been controlled by the Hevelli and Lutici tribes since 983. The Christian church in Havelberg, which had been taken over by revolting tribes, was re-established to convert the Wends.

In 1164, Duke Henry the Lion of Saxony defeated the rebellious Obotrites and Pomeranian dukes. The Pomeranian duchies and the Obodrite lands became Saxon territories. The Obodrite lands were renamed Mecklenburg, after their capital. In 1181, Mecklenburg and Pomerania became part of the Holy Roman Empire.

Saxon Eastern Marches

The Sorbian March was set up east of the Saale River in the 9th century. King Otto I later created a larger Saxon Eastern March in 937, covering the area between the Elbe, Oder, and Peene rivers. This march was home to various West Slavic tribes.

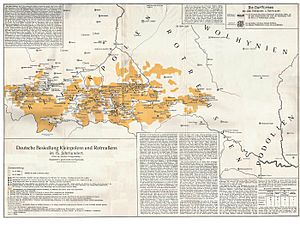

German settlers began moving into areas like the Margravate of Meissen and Transylvania in the 12th century. From the late 12th century, monasteries and cities were built in Pomerania, Brandenburg, Silesia, Bohemia, and Austria. In the Baltic region, the Teutonic Order founded a crusader state in the early 13th century.

Livonian Confederation

Terra Mariana (meaning "Land of Mary") was the official name for medieval Livonia. It was formed after the Livonian Crusade in what is now Estonia and Latvia. It became a principality of the Holy Roman Empire in 1207 and was later under the Pope's authority.

Medieval Livonia was ruled by different groups, including the Livonian Brothers of the Sword and a branch of the Teutonic Order. The Archbishop of Riga was the main religious leader. In 1561, during the Livonian War, Terra Mariana ended. Its lands were divided among Sweden, Lithuania (which later joined Poland), and Denmark.

Social and Population Changes

A big reason for the Ostsiedlung was a huge increase in population across Europe during the High Middle Ages. From the 11th to the 13th centuries, the population in Germany grew from about four million to twelve million people. During this time, people cleared forests to create more farmland. Even with new land, there were still many people looking for places to live.

Another reason was that many noble families had too many children who couldn't inherit land. After the success of the first crusades, these younger nobles saw a chance to gain new lands in the outer regions of the Empire.

Many German settlers moved to Eastern Central Europe. They brought German laws with them. Other settlers included people from Wallonia, Jews, Dutch, Flemish, and later Poles.

New Farming and Technology

The Medieval Warm Period, which started in the 11th century, brought warmer temperatures to Central Europe. This, along with new farming tools and methods, helped the population grow. For example, mills were built, and the "three-field system" of farming became common. More grain was grown, which meant more food for more people.

The new settlers brought their customs and language, but also new skills and tools. These were quickly adopted, especially in farming and crafts.

Large areas of forest were cleared to create more farmland. In some regions, like Silesia, the amount of cultivated land increased seven to twenty times during the Ostsiedlung.

New ways of organizing farms and villages were also introduced. Farmland was divided into "hufen" (like "hides" or plots of land). Larger villages replaced the smaller ones that used to have only a few farms. This completely changed how settlements looked. The way the land was shaped by these medieval settlements can still be seen today.

Dutch Settlers and Water Management

Flemish and Dutch settlers were among the first to move to Mecklenburg in the early 12th century. They later moved further east to Pomerania and Silesia, and south to Hungary. They were looking for new places to settle because their home areas were already crowded, and they had faced floods and famines.

These Dutch settlers were very skilled at managing water. They were in high demand in the undeveloped areas east of the Elbe River. They drained wet lands by digging networks of smaller ditches that led to main ditches. Roads connecting farms were built along these main ditches.

Local rulers actively recruited Dutch settlers. For example, in 1159/60, Albert the Bear allowed Dutch settlers to take over former Slavic settlements. A preacher named Helmold of Bosau wrote that Albert "sent to Utrecht and the Rhine region, and also to those who live by the ocean... the Dutch, Zealanders and Flemings, where he attracted a lot of people and let them live in the castles and villages of the Slavs."

Farming Tools

Slavs used plows before the western immigrants arrived. However, a new heavy plow called the "moldboard plow" was introduced in the mid-13th century. This plow dug deep into the earth and turned the soil over in one go. It was much better for heavier soils.

The moldboard plow also changed the shape of fields. Fields worked with the older plows were often square. But the moldboard plow worked best on long, rectangular fields, because it was heavy and hard to turn often. Growing oats and rye became more common. Farmers who used moldboard plows sometimes had to pay double taxes.

Pottery

Potters were among the first craftspeople to settle in rural areas. Slavic people used flat-bottomed pots. With the new settlers, new shapes like rounded jars were introduced. They also brought better ways of firing pottery, which made it stronger. This new type of pottery, called "Hard Grayware," became very common east of the Elbe by the late 12th century. By the 13th century, advanced ovens allowed for mass production of ceramic household items. People wanted more pots, jugs, and bowls, which had previously been made of wood.

In the 13th century, glazed pottery was introduced, and stoneware imports increased. These new technologies and knowledge changed life for both old and new settlers. They also brought improvements in other areas, like weapons and coins.

Architecture

The Slavic people east of the Elbe mainly built log houses. These were good for the local climate and there was plenty of wood. German settlers, especially from Franconia and Thuringia, brought the "half-timbering" style in the 13th century. This method used less wood and created strong, stable buildings that could have multiple floors. A new type of house was created that combined both styles. It had a timber frame around the ground floor, which could support a second floor made of half-timber.

Population and New Settlements

The Ostsiedlung led to a quick increase in population across Central and Eastern Europe. From the 12th to 13th centuries, many more people lived in these areas. This growth was due to new settlers arriving and the local populations growing after the settlements were established.

New tax systems also came with the German settlers. The old Slavic tax was a fixed amount based on village size. The new German tax depended on how much crop was actually grown. This meant settlers often paid higher taxes, though they sometimes got tax breaks for the first few years.

City Growth and New Towns

Examples of Ostsiedlung towns

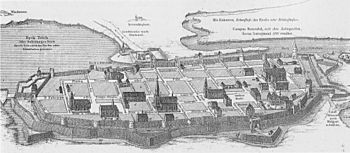

Poznań (Posen) was an Ostsiedlung town built next to an older castle. The new town had a rectangular street plan.

Greifswald in medieval Pomerania was a new town built in an empty area. Organizers planned it with rectangular blocks and a central market.

The development of Germania Slavica also involved building many new towns. There were already Slavic castle towns with markets outside their walls. But the new towns were different. Cities like Szczecin and Kraków grew a lot with new settlers from the late 12th century. Some cities, like Neubrandenburg, were built in completely new places. These new towns often had planned, grid-like street layouts with main roads and a central market square.

The towns founded during the Ostsiedlung were called "Free Towns" or "New Towns." This led to a rapid "urbanization of East Central Europe." These new towns were special because:

- They used "German town law," which gave towns much more control over their own administration and justice. Townspeople were free, had property rights, and were only judged by the town's own courts. Laws like the Lübeck Law and Magdeburg Law were copied and used in many new towns.

- They had permanent markets. Before, markets were only held sometimes. Now, people could trade freely, and marketplaces became the heart of the new towns.

- Their layout was planned, usually with a rectangular shape.

City Laws and Grants

Giving towns special "city rights" was important for attracting German settlers. These rights gave new residents many benefits. Even small settlements of local people could get these new rights. People called "locators" were hired to find settlers, divide land, and set up the new towns. These locators often came from the lower nobility or city merchants.

Spread of German City Laws

The Magdeburg Law and Lübeck Law were the most important German city laws used in the new settlements. They were models for most new cities. The Lübeck Law, from 1188, was used in about 100 cities along the Baltic Sea. The Magdeburg Law spread into Brandenburg, Saxony, Silesia, Poland, Bohemia, and other areas.

Religious Changes

Before the Ostsiedlung, there were attempts to convert the pagan Wends to Christianity. But a Slavic uprising in 983 stopped these efforts for almost 200 years. When new settlers arrived around 1150, Christianity spread more widely. The new settlers built wooden, and later stone, churches in their villages. Some churches, like St. Mary in Brandenburg, were built on top of old pagan holy sites. Monks, especially the Cistercians, played a big role in spreading faith and developing communities.

The Settlers

Most settlers were Germans from the Holy Roman Empire. Many Dutch settlers also took part, especially in the early 12th century. Some Danes, Scots, and local Wends also joined. Among the settlers were younger children of noble families who couldn't inherit land.

Settlers were invited by local rulers like dukes and princes. These rulers owned large areas of land that weren't being used much, so they didn't make much money. They offered good deals to new settlers, like land ownership and better legal rights. The landowners benefited because the new farmers made the land productive.

Most rulers hired "locators" to find settlers, divide the land, and set up the new communities. These locators organized the trips, advertised, and helped clear the land.

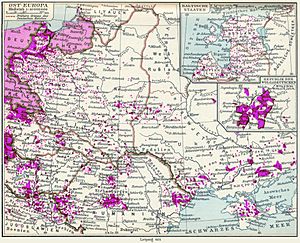

New towns were founded and given German town laws. The farming, legal, and technical methods of the immigrants, along with their success in Christianizing the local people, slowly changed the settlement areas. Slavic communities often adopted German culture. German culture and language stayed in some of these areas until the 20th century.

The migration slowed down a lot in the mid-14th century because of the Black Death. The population decreased, and some settlements were abandoned. About a century later, local Slavic leaders in Pomerania, Western Prussia, and Silesia again invited German settlers.

Assimilation: Cultures Blending

The Ostsiedlung led to cultures blending over centuries. Sometimes German settlers adopted Slavic ways, and sometimes Slavic people adopted German ways. It depended on the region and which group was larger.

Germans

German settlers in cities like Kraków and Poznań slowly became more Polish over about two centuries. The Sorbs also assimilated German settlers, but at the same time, small Sorbic communities were absorbed by the surrounding German-speaking population. Many towns in Central and Eastern Europe became places where many different ethnic groups lived together.

Local Slavic People

Even though the Slavic population was generally not as dense as in the Holy Roman Empire, some areas kept their Wendish populations for a long time and resisted blending in.

In Pomerania and Silesia, German migrants often built new villages on land given to them by Slavic nobles or monks, instead of settling in old Wendish villages. In some areas west of the Oder River, Wends were sometimes forced out, and their villages were rebuilt by settlers. However, the new villages often kept their old Slavic names.

In the Sorbian March, the situation was different. This area was close to Bohemia, which was ruled by a Slavic family loyal to the Empire. Here, German lords often worked with the Slavic people. German-Slavic relations were generally good.

The Ostsiedlung wasn't about discriminating against Wends. In fact, Wends paid lower taxes, so new settlers were often more profitable. While most settlers were Germans, Wends and other tribes also took part in the settlement. New settlers were chosen for their strength and farming skills, not their ethnicity.

Most Wends gradually blended in. However, in isolated rural areas where Wends were a large part of the population, they kept their culture. These included the Drevani Polabians, the Slovincians, Kashubs, and the Sorbs of Lusatia.

Language Exchange

The Ostsiedlung led to words being borrowed between German and Slavic languages. When Germans and Slavs lived side-by-side, they exchanged words. Words related to crafts, politics, farming, and food often moved from German into Slavic languages. For example, the German word for "brick" (Ziegel) came from an old German word. An example of a word borrowed from Slavic into German is the word for "border" (Grenize in Middle High German), which came from old Czech or Polish. City names also changed due to language exchange.

| Category | English | German | Polish | Czech | Slovakian | Hungarian |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Administration | mayor | Bürgermeister | burmistrz | purkmistr | richtár / burgmajster | polgármester |

| Administration | margrave | Markgraf | margrabia | markrabě | markgróf | őrgróf |

| Craft | brick | Ziegel | cegła | cihla | tehla | tégla |

| Food | pretzel | Brezel | precel | preclík | praclík | perec |

| Food | oil | Öl | olej | olej | olej | olaj |

| Agriculture | mill | Mühle | młyn | mlýn | mlyn | malom (mahlen) |

| Trade | (cart-)load | Fuhre | fura | fůra | fúra | furik |

| Others | flute | Flöte | flet | flétna | flauta | flóta |

Names of Places

Many Slavic and Wendish place names were adopted and changed over time. You can often recognize them by endings like "-ow" (like Spandau), "-vitz," or "-in." New villages were given German names, often ending with "-dorf" or "-hagen" in the north, and "-rode" or "-hain" in the south. Sometimes, the name of the settler's original home, like Lichtervelde in Flanders, became part of the new place name.

If a German settlement was built next to a Wendish one, the German village might adopt the Wendish name. Then, they would add words like "Klein-" (small) or "Wendisch-" for the Wendish village, and "Groß-" (large) or "Deutsch-" for the German one.

After World War II, many Eastern European countries changed German place names to Slavic ones. This was because they no longer wanted to remember the history of German settlement.

Conflicts

Sometimes, the settlement led to conflicts between ethnic groups. Local people, especially in towns, sometimes didn't like the newcomers, particularly if they didn't speak the local language. In some regions, native people were even forced out.

End of the Migration

There isn't one clear reason why the Ostsiedlung ended, or an exact end date. However, the movement slowed down a lot after 1300. In the 14th century, very few new settlements were founded with German-speaking colonists.

Several things might have caused this slowdown. The climate got colder around 1300, starting the "Little Ice Age." There was also a farming crisis in the mid-14th century. And the Black Death plague in 1347 caused a huge drop in population, leading to many settlements being abandoned. The end of the Ostsiedlung is often seen as part of this larger crisis of the 14th century.

Drang nach Osten

In the 19th century, as nationalism grew, people started to see the Ostsiedlung differently. In Germany and some Slavic countries, especially Poland, nationalists saw it as a sign of later German expansion and efforts to make others more German. They used the slogan Drang nach Osten (meaning "Drive or Push to the East").

However, historians say that the medieval settlements weren't based on any such ideology. They were driven by practical needs. As historian Buchholz wrote, the idea of a conflict between Slavs and Germans during the Ostsiedlung was an idea from the 19th century, not the Middle Ages. Settlements were open to "people of whatever origin and whatever craft."

Legacy of the Ostsiedlung

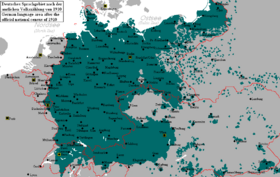

The wars and nationalist policies of the 20th century greatly changed the mix of ethnic groups and cultures in Central and Eastern Europe. After World War I, Germans in newly formed Poland were pressured to leave certain areas. During World War II, the Nazis moved many Germans from places like the Baltic states to occupied Poland.

The Nazis planned to create "living space" (Lebensraum) for Germans by expelling Poles and other Slavs. They used the idea of German superiority to justify their territorial claims. While their full plan was stopped by the war, they did start expelling Poles and settling Germans in annexed territories by 1944.

After World War II, the Potsdam Conference allowed the expulsion of Germans from Czechoslovakia, Poland, and Hungary. With Germany's defeat in 1945, nearly all Germans were expelled from former German territories east of the Oder-Neisse line, like Silesia and Pomerania. These areas were then settled by citizens of the new countries, such as Poles and Czechs.

However, some areas settled during the Ostsiedlung still remain part of modern Germany. These include parts of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Brandenburg, Saxony, and eastern Holstein. These areas have remained German in language and culture.

At the beginning of the 20th century, about 30 million Germans lived in the medieval colonization areas that were part of the German Empire and Austria-Hungary. After the borders of Germany moved westward in 1919 and especially in 1945, about 15 million Germans were forced to move to within Germany's new borders.

Images for kids

- Cultural assimilation

- German diaspora

- Zipser Willkür

- Transylvanian Saxon University

- Drang nach Osten

- Limes Saxoniae

- Barbarian invasions

- Wends

- Wendish Crusade

- Northern Crusades

- Medieval demography

- German exonyms

- Germanization

- Germanization of Poles during Partitions

- History of Germans in Russia and the Soviet Union

- Historical migration

- Josephine colonization

- Population transfer in the Soviet Union

- Polonization

- Pre-modern human migration

See also

In Spanish: Ostsiedlung para niños

In Spanish: Ostsiedlung para niños