Population transfer in the Soviet Union facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Population transfer in the Soviet Union |

|

|---|---|

| Part of Dekulakization, Forced settlements in the Soviet Union, and World War II | |

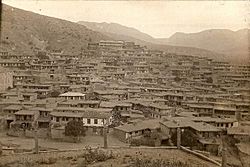

The empty Crimean Tatar village of Üsküt, near Alushta, photo taken in 1945 after the complete deportation of its inhabitants

|

|

General routes of deportation during the Dekulakization across the Soviet Union in 1930–1931

|

|

| Location | Soviet Union and occupied territories |

| Date | 1930–1952 |

| Target | Kulaks, peasants, ethnic minorities, and occupied territory citizens |

|

Attack type

|

ethnic cleansing, population transfer, forced labor, genocide, classicide |

| Deaths | ~800,000–1,500,000 in the USSR |

| Perpetrators | OGPU / NKVD |

| Motive | Russification, colonialism, cheap labor for forced settlements in the Soviet Union |

From 1930 to 1952, the government of the Soviet Union made many groups of people move from their homes. These orders came from the Soviet leader Joseph Stalin and were carried out by the NKVD official Lavrentiy Beria.

These forced moves can be put into a few main groups:

- Moving people who were seen as "anti-Soviet" or "enemies of the people."

- Moving entire groups of people based on their nationality.

- Moving people to work in new places.

- Moving people to fill areas where others had been removed.

The first time a whole group of people (called "kulaks") was moved was in 1930–31. Later, in 1937, the deportation of Soviet Koreans was the first time an entire ethnic group was moved.

Most of the time, people were sent to faraway, empty areas. This also included moving non-Soviet citizens from other countries into the Soviet Union. It's thought that at least 6 million people were forced to move within the Soviet Union. This included 1.8 million kulaks in 1930–31, 1 million farmers and ethnic groups in 1932–39, and about 3.5 million ethnic groups from 1940–52.

Records show that about 390,000 people died during the forced movement of kulaks. Up to 400,000 people died in forced settlements in the 1940s. Some historians believe the total number of deaths from these deportations could be as high as 1 to 1.5 million. Today, many historians call these forced moves a crime against humanity and ethnic persecution.

Two of these events, the deportation of the Crimean Tatars and the deportation of the Chechens and Ingush, are recognized as genocides by some countries and the European Parliament. In 1991, the Russian government passed a law that called all mass deportations "Stalin's policy of defamation and genocide."

The Soviet Union also forced people to move from areas it took over. More than 50,000 people died from the Baltic States. Between 300,000 and 360,000 Germans died during their expulsion from Eastern Europe due to Soviet actions like deportations, massacres, and forced labor camps.

Contents

Forced Movement of Social Groups

Many Soviet farmers were called "Kulaks" if they didn't want to join collective farms. This word used to mean wealthy farmers. "Kulak" was the most common reason for people to be deported. People labeled as kulaks continued to be moved until the early 1950s. For example, in 1951, kulaks were deported from Lithuanian SSR for "hostile actions."

Large numbers of "kulaks" were sent to Siberia and Central Asia. Soviet records from 1990 show that 1,803,392 people were sent to labor camps in 1930 and 1931. Of these, 1,317,022 made it to their destination. Smaller deportations continued after 1931. Between 1932 and 1940, 389,521 kulaks and their families died in these labor camps. Some estimates say that up to 15 million kulaks and their families were deported by 1937, and many died, but the exact number is not known.

Forced Movement of Ethnic Groups

In the 1930s, the idea of who was an "enemy of the people" changed. It moved from being about social class (like "kulak") to being about ethnic background. Joseph Stalin often removed ethnic groups he thought might cause trouble. Between 1935 and 1938, at least ten different nationalities were deported. When Germany invaded the Soviet Union in World War II, these forced ethnic movements greatly increased.

The deportation of Koreans was the first time an entire nationality was moved in the Soviet Union. In October 1937, almost all ethnic Koreans (171,781 people) were forced to move from the Russian Far East to empty areas in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan.

During Stalin's rule, many groups were deported, including:

- Poles (1939–1941 and 1944–1945)

- Romanians (1941 and 1944–1953)

- Estonians, Latvians, and Lithuanians (1941 and 1945–1949)

- Volga Germans (1941–1945)

- Crimean Tatars and Crimean Greeks (1944)

- Kalmyks, Balkars, Italians of Crimea, Karachays, Meskhetian Turks, Chechens, and Ingushs (1944)

It's estimated that between 1941 and 1949, nearly 3.3 million people were sent to Siberia and Central Asia. Some estimates say that up to 43% of these people died from diseases and malnutrition.

Forced Moves After Western Annexations (1939–1941)

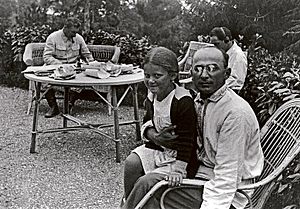

Lavrentiy Beria, the head of the NKVD (the Soviet secret police), was in charge of organizing these forced movements of ethnic groups.

After the Soviet Union invaded eastern Poland in 1939 (at the start of World War II), it took over these areas. Between 1939 and 1941, the Soviet government deported 1.45 million people from this region. Polish historians believe that about 63.1% of these people were Poles and 7.4% were Jews. While it was once thought that 1 million Polish citizens died, newer estimates based on Soviet records suggest about 350,000 people died from 1939–1945.

Similar events happened in the Baltic States (Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia). More than 200,000 people were deported from the Baltic region between 1940 and 1953. Another 75,000 were sent to the Gulag (forced labor camps). About 10% of all adults in the Baltic states were deported or sent to labor camps.

Many Romanians from Chernivtsi Oblast and Moldavia were also deported, with numbers ranging from 200,000 to 400,000.

Forced Moves During World War II (1941–1945)

During World War II, especially in 1943–44, the Soviet government deported about 1.9 million people to Siberia and Central Asia. For example, out of about 183,000 Crimean Tatars, 20,000 (10%) had served in German groups. Because of this, the Soviets moved all Tatars after the war. Vyacheslav Molotov, a Soviet official, said this decision was made because of "mass treason" during the war.

The Volga Germans and seven non-Slavic groups from Crimea and the northern Caucasus were deported. These included the Crimean Tatars, Kalmyks, Chechens, Ingush, Balkars, Karachays, and Meskhetian Turks. All Crimean Tatars were deported as a form of collective punishment on May 18, 1944, to Uzbekistan and other distant parts of the Soviet Union. NKVD data shows that nearly 20% died in exile within a year and a half. Crimean Tatar activists say this figure was closer to 46%.

Other groups moved from the Black Sea coast included Bulgarians, Crimean Greeks, Romanians, and Armenians.

The Soviet Union also deported people from areas it occupied, like the Baltic states, Poland, and German-occupied territories. A German study from 1974 estimated that over 600,000 German civilians died during their expulsion between 1945 and 1948.

By January 1953, there were 988,373 special settlers in Kazakhstan. This included 444,005 Germans, 244,674 Chechens, and 95,241 Koreans. As a result of these deportations, Kazakhs made up only 30% of their own country's population.

Post-War Deportations

After World War II, the German population of the Kaliningrad Oblast (formerly East Prussia) was expelled. Soviet citizens, mostly Russians, then resettled the empty area.

Poland and Soviet Ukraine also exchanged populations. Poles living east of the new border were sent to Poland (about 2.1 million people). Ukrainians living west of the border were sent to Soviet Ukraine (about 450,000 people).

Changes After Stalin

In February 1956, Nikita Khrushchev gave a speech where he criticized the deportations. He said they went against the ideas of Lenin.

He stated that the mass deportations of entire nations were not needed for military reasons. For example, the Karachay people were deported in late 1943. The same happened to the Kalmyk Republic. In March, all Chechen and Ingush peoples were deported. In April 1944, all Balkars were also deported.

A secret Soviet report from December 1965 showed that from 1940–1953, many people were deported from different regions:

- 46,000 from Moldova

- 61,000 from Belarus

- 571,000 from Ukraine

- 119,000 from Lithuania

- 53,000 from Latvia

- 33,000 from Estonia

Moving People for Work

The Soviet Union also moved people to work in remote, underpopulated areas. This was often done through "recruitment," especially in forced settlements where people were more willing to move for work. For example, workers for the Donbas and Kuzbass mining areas were often recruited this way.

Some notable campaigns for moving workers included:

- Virgin Lands campaign: A project to grow crops in new areas.

- Baku oil workers: In October 1942, about 10,000 oil workers and their families were moved from Baku to other oil-producing areas. This was done because of the threat of German invasion.

Returning People After World War II

After World War II ended in May 1945, millions of Soviet citizens were forced to return to the USSR. In February 1945, the United States and United Kingdom signed an agreement with the USSR at the Yalta Conference.

This agreement meant that all Soviet citizens, even those who didn't want to go back, were forced to return. This included people who had left Russia years before and become citizens of other countries. These forced returns happened from 1945 to 1947.

At the end of World War II, over 5 million "displaced persons" from the Soviet Union were in German captivity. About 3 million had been forced laborers in Germany.

Surviving prisoners of war (about 1.5 million) and other displaced people (over 4 million total) were sent to special Soviet "filtration camps." By 1946, most civilians and some prisoners of war were freed. Others were sent to labor groups or transferred to the NKVD (Gulag).

Modern Views on Deportations

Many historians, including Pavel Polian and Violeta Davoliūtė, believe these mass deportations were a crime against humanity. They are also often called Soviet ethnic cleansing. Terry Martin of Harvard University notes that Soviet policies could lead to ethnic cleansing against certain groups, while still building nations for others.

Some experts and countries go further, calling the deportations of the Crimean Tatars, Chechens, and Ingushs genocide. Raphael Lemkin, who created the term "genocide," believed it happened during the mass deportations of the Chechens, Ingush, Volga Germans, Crimean Tatars, Kalmyks, and Karachay.

The European Parliament recognized the deportation of the entire Chechen people in 1944 as an act of genocide in 2004.

On December 12, 2015, the Ukrainian Parliament officially recognized the deportation of Crimean Tatars as genocide. They set May 18 as the "Day of Remembrance for the victims of the Crimean Tatar genocide." The parliaments of Latvia and Lithuania also recognized this event as genocide in 2019. The Canadian Parliament did the same on June 10, 2019.

Some academics disagree with calling all deportations genocide. Professor Alexander Statiev argues that Stalin's government did not intend to wipe out these groups. Instead, he believes Soviet "political culture, poor planning, haste, and wartime shortages" caused the high death rates. He sees these deportations as an attempt to make "unwanted nations" fit in.

Deaths from Deportations

The number of deaths among deported people living in exile was very high. This was due to harsh climates in Siberia and Kazakhstan, diseases, malnutrition, and very hard work (up to 12 hours a day). There was also a lack of proper housing. Overall, it is thought that between 800,000 and 1,500,000 people died because of these forced moves.

Records from the NKVD show high death rates for these deported groups:

- Meskhetian Turks: 14.6% died

- Kalmyks: 17.4% died

- People from Crimea: 19.6% died

- Chechens, Ingush, and others from the Northern Caucasus: up to 23.7% died

The NKVD did not record extra deaths for Soviet Koreans, but estimates for their death rate range from 10% to 16.3%.

| Group | Estimated number of deaths | References |

|---|---|---|

| Kulaks 1930–1937 | 389,521 | |

| Chechens | 100,000–400,000 | |

| Poles | 90,000 | |

| Koreans | 16,500–40,000 | |

| Estonians | 5,400 | |

| Latvians | 17,400 | |

| Lithuanians | 28,000 | |

| Finns | 18,800 | |

| Hungarians | 15,000–20,000 | |

| Karachays | 13,100–35,000 | |

| Soviet Germans | 42,823–228,800 | |

| Kalmyks | 12,600–48,000 | |

| Ingush | 20,300–23,000 | |

| Balkars | 7,600–11,000 | |

| Crimean Tatars | 34,300–109,956 | |

| Meskhetian Turks | 12,859–50,000 | |

| TOTAL | 824,203–1,514,877 |

Additionally, around 300,000–360,000 Germans who were deported after World War II from Eastern Europe also died. However, the Soviet Army was not the only group involved in these expulsions.

Timeline of Major Forced Transfers

| Date of transfer | Targeted group | Approximate numbers | Place of initial residence | Transfer destination | Stated reasons for transfer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| April 1920 | Cossacks, Terek Cossacks | 45,000 | North Caucasus | Ukraine, northern Russian SFSR | Stopping Russian settlement in North Caucasus |

| 1930–1931 | Kulaks | 1,679,528- 1,803,392 | Most of Russian SFSR, Ukraine, other regions | Northern Russian SFSR, Ural, Siberia, North Caucasus, Kazakh ASSR, Kirghiz ASSR | Collectivization |

| 1930–1937 | Kulaks | 15,000,000 | Most of Russian SFSR, Ukraine, other regions | Northern Russian SFSR, Ural, Siberia, North Caucasus, Kazakh ASSR, Kirghiz ASSR | Collectivization |

| November–December 1932 | Peasants | 45,000 | Krasnodar Krai (Russian SFSR) | Northern Russia | Sabotage |

| May 1933 | People from Moscow and Leningrad without passports | 6,000 | Moscow and Leningrad | Nazino Island | To "cleanse" cities of unwanted people |

| February–May 1935; September 1941; 1942 | Ingrian Finns | 420,000 | Leningrad Oblast, Karelia (Russian SFSR) | Astrakhan Oblast, Vologda Oblast, Western Siberia, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Finland | |

| February–March 1935 | Germans, Poles | 412,000 | Central and western Ukraine | Eastern Ukraine | |

| May 1936 | Germans, Poles | 45,000 | Border regions of Ukraine | Ukraine | |

| July 1937 | Kurds | 1,325 | Border regions of Georgia, Azerbaijan, Armenia, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan | Kazakhstan, Kirghizia | |

| September–October 1937 | Koreans | 172,000 | Far East | Northern Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan | |

| September–October 1937 | Chinese, Harbin Russians | At least 17,500 | Southern Far East | Xinjiang,

Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan |

|

| 1938 | Persian Jews | 6,000 | Mary Province (Turkmenistan) | Deserted areas of northern Turkmenistan | |

| January 1938 | Azeris, Persians, Kurds, Assyrians | 6,000 | Azerbaijan | Kazakhstan | Iranian citizenship |

| January 1940 – 1941 | Poles, Jews, Ukrainians (including refugees from Poland) | 320,000 | Western Ukraine, western Byelorussia | Northern Russian SFSR, Ural, Siberia, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan | |

| July 1940 to 1953 | Estonians, Latvians & Lithuanians | 203,590 | Baltic states | Siberia and Northern Russian SFSR | |

| September 1941 – March 1942 | Germans | 855,674 | Povolzhye, the Caucasus, Crimea, Ukraine, Moscow, central Russian SFSR | Kazakhstan, Siberia | |

| August 1943 | Karachays | 69,267 | Karachay–Cherkess AO, Stavropol Krai (Russian SFSR) | Kazakhstan, Kirghizia, other | Banditism |

| December 1943 | Kalmyks | 93,139 | Kalmyk ASSR, (Russian SFSR) | Kazakhstan, Siberia | |

| February 1944 | Chechens, Ingush | 478,479 | North Caucasus | Kazakhstan, Kirghizia | Insurgency |

| April 1944 | Kurds, Azeris | 3,000 | Tbilisi (Georgia) | Southern Georgia | |

| May 1944 | Balkars | 37,406–40,900 | North Caucasus | Kazakhstan, Kirghizia | |

| May 1944 | Crimean Tatars | 191,014 | Crimea | Uzbekistan | |

| May–June 1944 | Greeks, Bulgarians, Armenians, Turks | 37,080 (9,620 Armenians, 12,040 Bulgarians, 15,040 Greeks) |

Crimea | Uzbekistan (?) | |

| June 1944 | Kabardins | 2,000 | Kabardino-Balkarian ASSR, (Russian SFSR) | Southern Kazakhstan | Collaboration with the Nazis |

| July 1944 | Russian True Orthodox Church members | 1,000 | Central Russian SFSR | Siberia | |

| November 1944 | Meskhetian Turks, Kurds, Hamshenis, Pontic Greeks, Karapapaks, Lazes and other inhabitants of the border zone | 115,000 | Southwestern Georgia | Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Kirghizia | |

| November 1944 – January 1945 | Hungarians, Germans | 30,000–40,000 | Transcarpathian Ukraine | Ural, Donbas, Byelorussia | |

| January 1945 | "Traitors and collaborators" | 2,000 | Mineralnye Vody (Russian SFSR) | Tajikistan | Collaboration with the Nazis |

| 1944–1953 | Families of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army | 204,000 | Western Ukraine | Siberia | |

| 1944–1953 | Poles | 1,240,000 | Kresy region | postwar Poland | Removal of people from new Soviet territory |

| 1945–1950 | Germans | Tens of thousands | Königsberg | West or Middle Germany | Removal of people from new Soviet territory |

| 1945–1951 | Japanese, Koreans | 400,000 | Mostly from Sakhalin, Kuril Islands | Siberia, Far East, North Korea, Japan | Removal of people from new Soviet territory |

| 1948–1951 | Azeris | 100,000 | Armenia | Kura-Aras Lowland, Azerbaijan | "Measures for resettlement of collective farm workers" |

| May–June 1949 | Greeks, Armenians, Turks | 57,680 (including 15,485 Dashnaks) |

The Black Sea coast (Russian SFSR), South Caucasus | Southern Kazakhstan | Membership in nationalist parties, Greek or Turkish citizenship |

| March 1951 | Basmachis | 2,795 | Tajikistan | Northern Kazakhstan | |

| April 1951 | Jehovah's Witnesses | 8,576–9,500 | Mostly from Moldavia and Ukraine | Western Siberia | Operation North |

| 1920 to 1953 | Total | ~20,296,000 |

See also

In Spanish: Deportaciones de pueblos en la Unión Soviética para niños

In Spanish: Deportaciones de pueblos en la Unión Soviética para niños

- Crimes against humanity under communist regimes

- Ethnic cleansing

- Excess mortality in the Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin

- Mass killings under communist regimes

- National operations of the NKVD

- World War II evacuation and expulsion

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |