Kalmyks facts for kids

| Хальмгуд / Xaľmgud | |

|---|---|

Kalmyks in the late 19th century. Picture taken in the Salsky Raion of the Don Host Oblast.

|

|

| Total population | |

| c. 195,000 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 179,547 | |

| 12,000 | |

| 325 | |

| 3,000 | |

| Languages | |

| Kalmyk Oirat, Russian | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Buddhism Minority Russian Orthodox Christianity, Tengrism, Mongolian shamanism, Islam |

|

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Mongols, especially Oirats, other Mongolic peoples | |

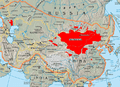

The Kalmyks are a special group of people who speak a Mongolic language. They are the only Mongolic-speaking people living in Europe. Most of them live in the eastern part of the European Plain in a dry, grassy area of Russia.

This area, west of the lower Volga River, was perfect for nomadic groups to graze their animals. The Volga River was even called "Itil" or "Idjil" in the old Oirat language, which means "pastures."

The Kalmyks' ancestors were nomadic people called Oirats from Western Mongolia. They moved to Eastern Europe three times over many centuries. The last big move was in the 1600s, when they formed the Kalmyk Khanate.

The Oirat language has different groups, like the Derbet, Torgut, and Khoshut. These groups live in different places, including Western Mongolia, China, and Russia. Even today, Kalmyks keep their unique group identities. They are also the only people in Europe who traditionally follow Buddhism. Some Kalmyk communities have also moved to places like the United States and France.

Contents

- Who are the Kalmyks? Their History and Origins

- The Early Days of the Oirats

- Times of Conflict and Alliances

- Oirat Power Grows Again

- The Torghut Journey West

- The Kalmyk Khanate: A New Home

- Life in the Russian Empire

- Russian Revolution and Civil War

- The Kalmyk Soviet Republic

- Forced Changes and Rebellions

- World War II and Exile

- Coming Home from Exile

- What Does "Kalmyk" Mean?

- Kalmyk Subgroups

- Kalmyk Population Numbers

- Where Kalmyks Live

- Kalmyk Religion and Beliefs

- Kalmyk Language

- Kalmyk Writing System

- Famous Kalmyk People

- Images for kids

Who are the Kalmyks? Their History and Origins

The Early Days of the Oirats

Modern Kalmyks come from the Oirats of Mongolia. Their old grazing lands covered parts of Kazakhstan, Russia, Mongolia, and China. After the Yuan dynasty fell in China in 1368, the Oirats became strong. They fought against other Mongol groups and Chinese dynasties for about 400 years. This long struggle ended in 1757 when the Oirats of the Dzungar Khanate were defeated by the Qing Empire.

At the start of this period, the Western Mongols called themselves the Four Oirat. This group included four main tribes: Khoshut, Choros, Torghut, and Dörbet. They wanted power, just like the descendants of Genghis Khan. Sometimes, other smaller tribes joined them.

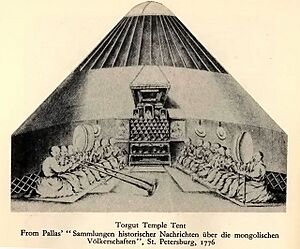

These nomadic tribes lived on the grassy plains of western Inner Asia. They moved between Lake Balkhash in Kazakhstan and Lake Baikal in Russia. They lived in yurts, which are round, portable tents. They raised cattle, sheep, horses, donkeys, and camels.

Times of Conflict and Alliances

The Four Oirat was a political group formed by the main Oirat tribes. From the 1400s to the 1600s, they had a strong cavalry unit of 10,000 horsemen. They went back to their traditional nomadic life after the Yuan dynasty ended. The Oirats formed this alliance to protect themselves and to try to unite all of Mongolia.

The Oirats had a special connection to Genghis Khan. His brother, Qasar, was in charge of the Khoshut tribe. This gave them some political importance.

The Oirat alliance was not very organized. It didn't have one central leader or a single army. They also didn't have uniform laws until 1640.

Each Oirat tribe was led by a noyon or prince. These leaders were quite independent. This often led to rivalries and small fights between the tribes.

For a short time, under the leader Esen, the Four Oirat united Mongolia. But after Esen died in 1455, the alliance broke apart. This led to more conflicts between the Oirats and the Eastern Mongols. Later, a young boy named Dayan Khan, with the help of Mandukhai Khatun, brought the Oirats back under Mongolian rule.

After Dayan died in 1543, the fighting between the Oirats and the Khalkhas started again. The Oirats were pushed westward. But they kept fighting back. An old Oirat song, "The Rout of Mongolian Sholoi Ubashi Khuntaiji," tells about an Oirat victory in 1587.

Oirat Power Grows Again

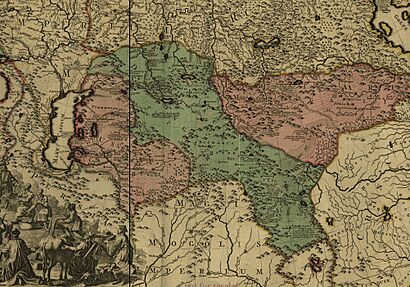

In the early 1600s, the Oirats were pushed west into what is now eastern Kazakhstan. The Torghut tribe became the westernmost Oirats. They lived near the Tarbagatai Mountains and along the Irtysh River.

The Torghuts couldn't trade with Muslim towns because of the Kazakhs. So, they started trading with the new Russian outposts in Siberia. Russia wanted to trade with Asia.

The Khoshut tribe was the easternmost Oirat group. They lived near Lake Zaysan. They built several monasteries there. The Khoshut leaders, Baibagas Khan and Güshi Khan, were the first Oirat leaders to become Tibetan Buddhists.

In the middle were the Choros, Dörbet, and Khoid tribes, known as the "Dzungar people". Their leader, Erdeni Batur, tried to unite the Oirats again. He built a capital city and encouraged diplomacy, trade, and farming. He also tried to get modern weapons.

But not all Oirat leaders wanted to be united. This disagreement led to some tribes moving away. Kho Orluk led the Torghut tribe and some Dörbet people west to the Volga region. There, his family formed the Kalmyk Khanate. Güshi Khan took part of the Khoshut tribe to the Tibetan Plateau to protect Tibet and Buddhism. Erdeni Batur and his family formed the Dzungar Khanate, which became very powerful in Central Asia.

The Torghut Journey West

In 1618, the Torghut tribe and some Dörbet Oirats (about 200,000–250,000 people) decided to move. They left the Irtysh River area and traveled to the lower Volga region. This area was south of Saratov and north of the Caspian Sea. Their leader was Kho Orluk. They were the largest Oirat tribe to move.

They traveled west through southern Siberia, avoiding their enemies, the Kazakhs. Along the way, they raided Russian settlements and Kazakh camps.

There are a few ideas why they moved. Some think there was disagreement among the Oirat tribes because one leader tried to take too much control. Others believe the Torghuts needed new pastures. Their old lands were getting crowded by Russians, Kazakhs, and Dzungars. A third idea is that they were tired of the constant fighting between the Oirats and the Altan Khanate.

The Kalmyk Khanate: A New Home

Self-Rule and Power (1630–1724)

When the Oirats arrived in the lower Volga region in 1630, the land was claimed by Tsardom of Russia. But it was not very populated. Russia wasn't ready to settle the area and couldn't stop the Oirats from moving in. Russia wanted to make sure the Oirats didn't become friends with their Turkic neighbors. So, the Kalmyks became allies with Russia and signed a treaty to protect Russia's southern border.

The Oirats quickly took control of the area. They pushed out most of the local people, the Nogai Horde. Many Nogais fled to the Caucasus or the Black Sea. Smaller groups of Nogais sought protection from the Russians. Other nomadic tribes became subjects of the Oirats.

At first, the relationship between Russians and Oirats was difficult. Both sides often raided each other's settlements. Many agreements were signed to ensure the Oirats' loyalty and military help. Even though the Oirats were subjects of the Tsar, their loyalty was often just on paper.

The Oirats governed themselves using a document called the "Great Code of the Nomads." This code was created in 1640 by the Oirats and some Khalkha Mongols. It set rules for all parts of nomadic life.

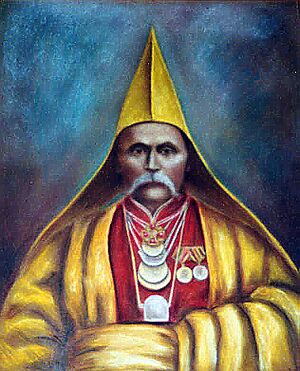

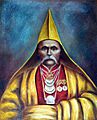

The Oirats became a strong power in the borderlands. They often teamed up with the Russian Empire against Muslim groups in the south. During the time of Ayuka Khan, the Oirats became very powerful. Russia often used Oirat cavalry in its military campaigns. Ayuka Khan also fought against the Kazakhs and other groups. These wars showed how important the Kalmyk Khanate was. It acted as a buffer zone between Russia and the Muslim world.

To get Oirat cavalry, Russia paid the Oirat Khan and nobles with money and goods. Russia treated the Oirats like the Cossacks. But these payments didn't stop the raiding. Sometimes, both sides didn't keep their promises.

Russia also allowed the Oirats to trade without taxes in Russian border towns. The Oirats could trade their animals and goods from Asia for Russian products. They also traded with other Turkic tribes. This trade brought a lot of benefits to the Oirat leaders.

This period, from 1630 to 1724, was called the "Frontier Period." During this time, there wasn't much mixing between Kalmyks and Russians. They mainly traded goods. Political contacts were mostly about treaties. Some Kalmyk nobles became more like Russians, hoping for Russian help. But Russian support became more important for control later on.

During Ayuka Khan's rule, the Kalmyk Khanate was at its strongest. It had a good economy from free trade with Russia, China, Tibet, and Muslim neighbors. Ayuka Khan also stayed in touch with his Oirat relatives in Dzungaria and the Dalai Lama in Tibet.

From Oirat to Kalmyk: A Name Change

Historically, Oirats called themselves by their tribe names. In the 1400s, three main Oirat groups formed an alliance called "Dörben Oirat." In the early 1600s, another Oirat alliance formed, which became the Dzungar Empire. While the Dzungars were building their empire, the Khoshuts formed the Khoshut Khanate in Tibet. The Torghuts formed the Kalmyk Khanate in the lower Volga region.

After settling, the Oirats started calling themselves "Kalmyk." This name was supposedly given to them by their Muslim neighbors and later used by the Russians. The Oirats used this name when dealing with outsiders. But among themselves, they still used their tribal names.

Not all Oirat tribes in the Volga region accepted the name "Kalmyk" right away. Even in 1761, the Khoshut and Dzungars still called themselves Oirats. But the Torghuts used "Kalmyk" for themselves and the other tribes.

European scholars often called all Western Mongolians "Kalmyks." But the Western Mongols in China and Mongolia saw "Kalmyk" as an insult. They preferred to use "Oirat" or their tribal names.

Over time, the Oirat descendants in the Volga region accepted the name "Kalmyk." Another common name for them was Ulan Zalata, meaning "red-buttoned ones."

Losing Freedom (1724–1771)

In January 1771, the Russian government's control became too much. A large part of the Kalmyks (about 170,000–200,000 people) decided to move back to their old homeland, Dzungaria. They hoped to bring back the Dzungar Khanate and Mongolian independence.

Ubashi Khan, the last Kalmyk Khan, led this journey. He sent 30,000 cavalry to get weapons before they left. The 8th Dalai Lama gave his blessing and set the departure date. But when it was time to leave, the Volga River ice was weak. Only the Kalmyks on the eastern bank (about 200,000 people) could leave. The 100,000–150,000 people on the western bank had to stay. Catherine the Great then punished the important nobles who stayed behind.

About five-sixths of the Torghut tribe followed Ubashi Khan. Most of the Khoshut, Choros, and Khoid tribes also went. But the Dörbet Oirat tribe decided to stay.

Catherine the Great ordered the Russian army, Bashkirs, and Kazakhs to stop the migrants. But the Kalmyks faced raids from Kazakhs, thirst, and starvation. About 85,000 Kalmyks died on their way to Dzungaria.

After failing to stop them, Catherine abolished the Kalmyk Khanate. All government power went to the governor of Astrakhan. The title of Khan was removed. The highest Kalmyk leader left was the Vice-Khan. By appointing this leader, Russia now had full control over Kalmyk affairs.

After seven months, only about one-third (66,073 people) of the original group reached Balkhash Lake in China. This journey became famous in a book called The Revolt of the Tartars.

The Qing dynasty in China moved the Kalmyks to five different areas to prevent them from rebelling. They also made the Kalmyks stop their nomadic life and become farmers. This was a way for the Qing to weaken them.

Life in the Russian Empire

After the 1771 exodus, the Kalmyks who stayed in Russia continued their nomadic life. They moved their herds between the Don and Volga Rivers. They spent winters in the lowlands near the Caspian Sea. In spring, they moved to higher grounds along the Don River.

Even with their big population loss, the Torghut tribe was still the largest among the remaining Kalmyks. Other groups included Dörbet Oirats and Khoshut. Smaller groups like the Choros and Khoit were absorbed into the larger tribes.

The problems that caused the 1771 exodus still affected the Kalmyks. After the exodus, some Torghuts joined a rebellion led by Yemelyan Pugachev. They hoped he would help them regain their independence. After the rebellion was defeated, Catherine the Great changed the leadership. The Vice-Khan position was moved from the Torghut tribe to the Dörbet tribe. The Dörbet princes had stayed loyal to the government.

The government divided the Kalmyks into three administrative units. These units were linked to the governments of Astrakhan, Stavropol, and the Don. A special Russian official, called "Guardian of the Kalmyk People," was appointed. Some small groups of Kalmyks were also moved to other rivers and Siberia.

The dominant Dörbet tribe was split into three units. Those in the western Kalmyk Steppe were called Baga (Lesser) Dörbet. Those in Stavropol province were called Ike (Greater) Dörbet. The Kalmyks of the Don became known as Buzava. Even though they were from different tribes, the Buzava claimed to be from the Torghut tribe. In 1798, Tsar Paul I recognized the Don Kalmyks as Don Cossacks. This meant they got the same rights as Russian Cossacks in exchange for military service. Kalmyk cavalry even entered Paris at the end of the Napoleonic Wars.

Over time, Kalmyks slowly started building permanent settlements with houses and temples. In 1865, Elista, the future capital of Kalmykia, was founded. This process continued even after the October Revolution of 1917.

Russian Revolution and Civil War

After the February Revolution in 1917, Kalmyk leaders hoped for more freedom. But this hope faded when the Bolsheviks took control in November 1917.

Groups against Communism formed the White movement. They created a "White Army" to fight the Red Army. Many Cossacks, including Don Kalmyks, joined the White Army. They didn't like the Bolsheviks' policies.

The revolution divided the Kalmyk people. Some were unhappy with the Tsarist government for taking their land. But others disliked Bolshevism because of their loyalty to traditional leaders and the conflict over land with Russian peasants.

Kalmyk nobles tried to join the Astrakhan Cossacks to fight the Bolsheviks. But the Red Army took control of Astrakhan and the Kalmyk steppe, stopping them.

After taking Astrakhan, the Bolsheviks were harsh towards the Kalmyk people. They attacked Buddhist temples and clergy. Eventually, the Bolsheviks forced about 18,000 Kalmyk horsemen into the Red Army. But many of them still joined the White Army.

Most Don Kalmyks also sided with the White Movement to protect their Cossack way of life. They fought under White army generals. The fighting was very destructive for the Don Cossacks, including the Kalmyks. Many died from fighting, starvation, or disease. Some say the Bolsheviks killed a huge number of Don Cossacks.

By October 1920, the Red Army defeated the White army. About 150,000 White soldiers and their families had to leave Russia. A small group of Don Kalmyks escaped to Europe. They settled in places like Belgrade, Bulgaria, and France. In 1922, some returned home under a promise of safety, but some were imprisoned and executed.

The Kalmyk Soviet Republic

The Soviet government created the Kalmyk Autonomous Oblast in November 1920. It combined Kalmyk settlements from different regions. Elista became its capital.

In October 1935, it became the Kalmyk Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic. The main jobs were raising cattle, farming, and fishing. There was no industry.

Forced Changes and Rebellions

In 1922, Mongolia offered to help Kalmyks during a famine, but Russia refused. About 71,000–72,000 Kalmyks died. The Kalmyks rebelled against Russia in 1926, 1930, and 1942–1943. In March 1927, the Soviets sent 20,000 Kalmyks to Siberia. Soviet scientists also tried to make Kalmyks believe they were not Mongols.

In 1929, Joseph Stalin ordered forced collectivization of farms. This made Astrakhan Kalmyks give up their nomadic life and settle in villages. Herdsmen with more than 500 sheep were sent to labor camps in Siberia.

World War II and Exile

In June 1941, the German army invaded the Soviet Union. They took some control of the Kalmyk Republic. But in December 1942, the Red Army took it back. On December 28, 1943, the Soviet government accused the Kalmyks of helping the Germans. They deported the entire Kalmyk population, even soldiers, to Central Asia and Siberia. This happened at night in winter, without warning, in unheated cattle cars.

Many Kalmyks died during the first few months of exile. From 1945 to 1950, 15,206 Kalmyks died, and 7,843 were born.

The Kalmyk Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic was quickly dissolved. Its land was divided among neighboring regions. Since no Kalmyks lived there, the Soviet authorities changed Kalmyk town names to Russian names. For example, Elista became Stepnoi.

Coming Home from Exile

About half of the Kalmyk people (97,000–98,000) who were sent to Siberia died before they were allowed to return home in 1957. The Soviet government also banned teaching the Kalmyk Oirat language during their exile. The Kalmyks' main goal was to move to Mongolia. A Russian law from 1991 called these repressions an act of genocide.

In 1957, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev allowed the Kalmyks to return. But they found their homeland had been settled by Russians and Ukrainians. On January 9, 1957, Kalmykia became an autonomous oblast again. On July 29, 1958, it became an autonomous republic within Russia.

In the years that followed, poor planning of farms and water projects led to a lot of desertification. Also, factories were built without checking if they would be good for the economy.

In 1992, after the Soviet Union broke up, Kalmykia chose to remain an autonomous republic of Russia. But the breakup caused a collapse of the economy. This led to many young Kalmyks leaving Kalmykia for better jobs and education.

In 1992, the local government changed the republic's name to Khalmg Tangch. In 1993, Kalmyk authorities claimed land in the Volga delta that was not returned to them in 1957. This land dispute with other regions continued, but no border changes were made.

Kalmyks have mostly kept their unique identity. Genetic studies show they have strong Mongol roots. They also show that entire Kalmyk families moved to the Volga region, not just men. This is different from many other nomadic groups.

Today, Kalmykia has good ties with Mongolia. During the Russian invasion of Ukraine since 2022, Kalmyks have been reported to have a high number of casualties among Russian forces.

What Does "Kalmyk" Mean?

The name "Kalmyk" comes from a Turkic word meaning "remnant" or "to remain." Turkic tribes might have used this name as early as the 1200s. An Arab geographer first used the term for the Oirats in the 1300s. Russian writings mentioned "Kolmak Tatars" in 1530. A map from 1544 showed the land of the "Kalmuchi." However, the Oirats themselves did not use this name for a long time.

Kalmyk Subgroups

The main Kalmyk subgroups are Baatud, Dörbet, Khoid, Khoshut, Olot, Torghut, and Buzava. The Torghuts and Dörbets are the largest groups. The Buzavs are a small group and are considered the most influenced by Russian culture.

Kalmyk Population Numbers

| year | population |

|---|---|

| 1897 |

190,648

|

| 1926 |

128,809

|

| 1939 |

129,786

|

| 1959 |

100,603

|

| 1970 |

131,318

|

| 1979 |

140,103

|

| 1989 |

165,103

|

| 2002 |

174,000

|

| 2010 |

183,372

|

Where Kalmyks Live

Kalmyks mainly live in the Republic of Kalmykia, a part of Russia. Kalmykia is in southeastern Europe, between the Volga and Don rivers. It borders other Russian regions and the Caspian Sea.

After the Soviet Union broke up, many young Kalmyks moved from Kalmykia. They went to bigger Russian cities like Moscow and St. Petersburg, and also to the United States. They did this to find better education and jobs. This trend continues today.

Currently, Kalmyks are the majority of the population in Kalmykia. In 2021, there were 159,138 Kalmyks in Kalmykia, making up 62.5% of the total population. Kalmyks also have more children than Russians, and their population is younger. This means the Kalmyk population is expected to keep growing.

Kalmyk Religion and Beliefs

The Kalmyks are the only people in Europe whose main religion is Buddhism. They became Buddhists in the early 1600s. They follow the Gelugpa sect of Tibetan Buddhism, also known as the Yellow Hat sect. This religion comes from the Indian Mahayana form of Buddhism.

Historically, Kalmyk religious leaders (lamas) were trained in Tibet or on the steppe. These lamas gave spiritual guidance and medical advice. They had a lot of political influence among the nobles and the people. Joining the monastic system was often the only way for commoners to learn to read and gain respect.

The Oirats also built stone monasteries in eastern Kazakhstan. Remains of these monasteries have been found in places like Almalik and Kyzyl-Kent.

The Russian government and the Russian Orthodox Church tried to convert people of other religions to Christianity. They wanted to remove foreign influences and make new areas loyal to Russia.

In the 1700s, some Kalmyks became Catholic, but not many. More Kalmyks converted to Islam. Some Kalmyk Muslims were called Tomuts, formed from marriages between Kalmyk women and Kazakhs. Another group, the Sherets, also converted to Islam. Today, Sart Kalmyks in Kyrgyzstan are mostly Sunni Muslims.

A small number of Kalmyk-Cossack families in Belarus became Jewish in the early 1800s.

The Tsarist government's efforts to convert Kalmyks to Christianity were mostly unsuccessful. However, some Kalmyk nobles did convert, often for political reasons. For example, the children of Donduk-Ombo, a Kalmyk Khan, converted. Another important convert was Peter Taishin, the grandson of Ayuka Khan.

Later, Russian and German settlers took the best land along the Volga River. This made it harder for Kalmyks to graze their herds. Some Kalmyk leaders led their groups to Christianity to get economic benefits.

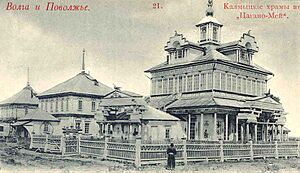

To discourage the nomadic monastic life, the government required permanent temples to be built in specific places. Russian architects were often used. This made Kalmyk temples look more like Russian Orthodox churches. For example, the Khosheutovsky khurul looks like the Kazan Cathedral in St. Petersburg.

After the Kalmyk Khanate was abolished in 1771, the Tsarist government tried to weaken the lamas' influence. They limited contact with Tibet. The Tsar also started appointing the Šajin Lama, the head lama of the Kalmyks. Economic problems also forced many monasteries to close. This policy worked, and the number of Kalmyk monasteries decreased in the 1800s.

| Year | Number |

|---|---|

| early 19th century | 200 |

| 1834 | 76 |

| 1847 | 67 |

| before 1895 | 62 |

| before 1923 | 60+ |

Like the Tsarist government, the Communist government knew how much influence the Kalmyk clergy had. In the 1920s and 1930s, the Soviet government tried to get rid of religion. They destroyed Kalmyk temples (khuruls) and monasteries. They took property and harassed or killed clergy and believers. Religious items and books were destroyed. Young men were not allowed to get religious training.

By 1940, all Kalmyk Buddhist temples were closed or destroyed. The clergy were systematically oppressed. When the Kalmyks were exiled in 1944, their religion was almost completely suppressed. When they returned in 1957, they tried to restore their religion and build a temple, but they failed.

By the 1980s, most Kalmyks had not received any formal religious guidance. However, in the late 1980s, the Soviet government changed its policy and allowed more religious freedom. The first Buddhist community was formed in 1988. By 1995, there were 21 Buddhist temples, 17 Christian places of worship, and 1 mosque in Kalmykia.

On December 27, 2005, a new khurul called "Burkhan Bakshin Altan Sume" opened in Elista. It is the largest Buddhist temple in Europe. The Kalmyk government wanted to build a great temple to be an international learning center for Buddhist scholars. It also serves as a memorial to the Kalmyk people who died in exile.

The Kalmyks in Kyrgyzstan are called "Sart Kalmyks." They mostly live in the Karakol region. They have adopted the Turkic language and culture of the Kyrgyz people. As a result, almost all of them are now Muslim.

However, Kalmyks elsewhere mostly remain faithful to Tibetan Buddhism. In Kalmykia, many Buddhist temples have been built with government help. The Kalmyk people recognize Tenzin Gyatso, 14th Dalai Lama as their spiritual leader. They also recognize Erdne Ombadykow, a Kalmyk American, as their supreme lama. The Dalai Lama has visited Elista many times. Buddhism and Christianity are recognized as state religions. In October 2022, Erdne Ombadykow condemned the Russian invasion of Ukraine and left Russia. In January 2023, he was labeled a "foreign agent" in Russia.

Kalmyk Language

The Kalmyk Oirat language is part of the Eastern branch of Mongolic languages. This means it is somewhat close to Standard Mongolian.

However, some linguists say Kalmyk Oirat belongs to the Western branch. They believe it is more different from Standard Mongolian because it developed separately. They also say Kalmyk and Oirat are distinct languages, mainly because Kalmyk has adopted many Russian words.

The main dialects of Kalmyk are Torghut, Dörbet, and Buzava. Minor dialects include Khoshut and Olöt. The differences between dialects are small. The dialects of nomadic Kalmyk tribes were less influenced by Russian.

The Dörbets and later Torghuts who moved to the Don Host Oblast became known as Buzava (or Don Kalmyks). Their dialect developed from close interaction with Russians. In 1798, the Russian government recognized the Buzava as Don Cossacks. This led to their dialect including many Russian words.

In 1938, the Kalmyk language started using the Cyrillic alphabet for writing. During World War II, when Kalmyks were exiled, they were not allowed to speak Kalmyk in public. As a result, the younger generation did not learn the language formally.

When they returned from exile in 1957, Kalmyks mostly spoke and published in Russian. So, younger Kalmyks today mainly speak Russian. This is a concern for many. The Kalmyk government has tried to revive the Kalmyk language. For example, shop signs now often include Kalmyk words.

According to UNESCO's 2010 report, the Kalmyk language is considered definitely endangered.

Kalmyk Writing System

In the 1600s, Zaya Pandita, a Khoshut Buddhist monk, created a writing system called Clear Script. It was based on the old vertical Mongol script and was designed to better show the sounds of the Oirat language. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, Clear Script was used less and less. In 1923, the Kalmyks stopped using it and started using the Cyrillic script. In 1930, scholars tried a modified Latin alphabet, but it wasn't used for long.

Famous Kalmyk People

- Maria Kirbasova, a Russian human rights activist.

- Kristina Anna Evdokia Bange (half Kalmyk).

- Irina Kukanova (Kristina's mother).

Political Leaders

- Kirsan Ilyumzhinov - First President of Kalmykia, former President of the World Chess Federation.

- Vladimir Lenin (possibly one-quarter Kalmyk) - Russian revolutionary and political thinker.

- Ilya Ulyanov (half Kalmyk).

- Oka Gorodovikov - A general in the Red Army.

- Lavr Kornilov - A general in the Imperial Russian Army during World War I.

Khans of the Kalmyk Khanate

- Kho Orluk

- Shukhur Daichin — 1654–1661

- Puntsug (Monchak) — 1661–1669

- Ayuka Khan — 1669–1724

- Tseren Donduk Khan — 1724–1735

- Donduk Ombo Khan — 1735–1741

- Donduk Dashi Khan — 1741–1761

- Ubashi Khan — 1761–1771

Athletes

- Sanan Sjugirov

- Batu Khasikov

- Mingiyan Semenov

- Sandje Ivanchukov

- Jean Djorkaeff (half Kalmyk)

- Youri Djorkaeff (one-quarter Kalmyk)

- Oan Djorkaeff (one-eighth Kalmyk)

- Liudmila Bodnieva

Images for kids

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |