Battle of Leuthen facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Leuthen |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Third Silesian War | |||||||

Storming of the breach by Prussian grenadiers, Carl Röchling |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 36,000 167 guns |

65,000 210 guns |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1,141 killed 5,118 wounded 85 captured Total: 6,344 casualties |

3,000 killed 7,000 wounded 12,000 captured Total: 22,000 casualties 116 guns captured |

||||||

The Battle of Leuthen was a major battle fought on December 5, 1757. It was part of the Seven Years' War and the Third Silesian War. In this battle, Frederick II of Prussia led his army to a huge victory. They completely defeated a much larger Austrian army. This win helped Prussia keep control of a region called Silesia.

The battle took place near the town of Leuthen (which is now Lutynia, Poland). Frederick used clever tactics and his army's excellent training. He pretended to attack one part of the Austrian army. Meanwhile, he secretly moved most of his smaller army behind some low hills. This surprise attack hit the Austrians on their side, where they least expected it. The Austrian commander, Prince Charles, was very confused.

In just seven hours, the Prussian army crushed the Austrians. This victory wiped out all the gains the Austrians had made earlier that year. Just two days later, Frederick began to attack Breslau. The city surrendered by December 20. Leuthen was the last battle where Prince Charles led the Austrian army. After this defeat, Empress Maria Theresa replaced him. The battle also made Frederick famous as a brilliant military leader.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened

The Seven Years' War was a big global conflict. In Europe, it was mainly a fight between Frederick the Great of Prussia and Maria Theresa of Austria. Their rivalry began in 1740. That's when Frederick attacked and took over Silesia, a rich area. The Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1748 ended an earlier war. It officially gave Silesia to Prussia.

Maria Theresa signed the treaty to buy time. She wanted to rebuild her army and make new friends (alliances). Her goal was to get Silesia back and become more powerful in the Holy Roman Empire. At the same time, France wanted to challenge Britain's power in trade.

By 1754, tensions grew between Britain and France in North America. Maria Theresa saw this as a chance to get her land back. France and Austria, who used to be enemies, decided to work together. Maria Theresa even agreed that her daughter, Marie Antoinette, would marry the French prince. This led Britain to team up with Frederick II of Prussia. This shift in alliances was called the Diplomatic Revolution.

When the war started in 1756, Frederick quickly took over Saxony. He then fought in Bohemia, beating the Austrians at the Battle of Prague in May 1757. But while he was away fighting in the west, the Austrians took back Silesia. Prince Charles captured the city of Schweidnitz. Then he moved on to Breslau in lower Silesia.

Frederick rushed back to Silesia. He learned that Breslau had fallen in late November. He and his 22,000 soldiers marched 274 kilometers (170 miles) in just 12 days! They met up with other Prussian troops near Liegnitz. Now, Frederick had about 33,000 soldiers and 167 cannons. They arrived near Leuthen to face 66,000 Austrians.

The Battlefield and Armies

Lower Silesia is mostly flat, fertile land. It has gentle hills, not steep mountains. This made it easy to see enemies coming. But it also meant there weren't many places to hide troops. The ground was soft in some areas, which could slow down soldiers or muffle sounds.

The area around Leuthen had several small villages. These included Nypern to the north and Gohlau to the southeast. A main road connected these villages to Breslau.

Austrian Army Positions

Prince Charles and his second-in-command, Count Leopold Joseph von Daun, knew Frederick was coming. They set up their army facing west. Their battle line was about 8 kilometers (5 miles) long. The village of Leuthen was in the middle of their line. Prince Charles set up his command post in a church tower there. He placed most of his soldiers on his right side (north). He also had soldiers from different parts of the Holy Roman Empire.

Prussian Army Strengths

Frederick knew the area very well from earlier training exercises. On December 4, 1757, he looked at the land with his generals. He saw a line of low hills that could hide his troops. These hills were called Schleierberg, Sophienberg, Wachberg, and Butterberg.

Frederick's army was smaller, but it was one of the best in Europe.

- His infantry (foot soldiers) could fire their muskets very fast. They could fire at least four shots a minute, twice as fast as most other armies.

- They could also move and march faster than other armies.

- His artillery (cannons) could be moved quickly to support the infantry.

- His cavalry (soldiers on horseback) were very well trained. They could charge together, side-by-side, at a full gallop.

The Battle Unfolds

Frederick's Clever Trick

The morning was foggy, which helped Frederick. He left a small group of cavalry and infantry in front of the northern end of the Austrian line. This was a trick! Frederick then moved the rest of his army towards Leuthen. Prince Charles saw some movement and thought the Prussians were leaving. He even moved his reserve troops to his right side to protect it. This made his army line much longer and weaker in other places.

While the small Prussian group kept Prince Charles busy, the main Prussian army moved secretly. They marched behind the low hills, completely hidden from the Austrians. They went all the way around the Austrian army's left side.

The Surprise Attack

The Prussian infantry marched south, staying hidden. When they had passed the Austrian left side, they turned to face the enemy. The entire Prussian army was now in a battle line, facing the weakest part of the Austrian army. Hans Joachim von Zieten's cavalry also moved into position.

The Prussian cannons were hidden behind the Butterberg hill. They waited to fire at the same time as the infantry attacked. Most of the Prussian army was now facing the smallest part of the Austrian line. The small group of Prussians still at the Austrian right continued to pretend they would attack there.

The Austrians were shocked when the Prussians appeared on their left side! The Prussian infantry, in two lines, charged the weakest part of the Austrian line. Austrian officers tried to turn their lines to face the attack. Franz Leopold von Nádasdy, who was in charge of that side, asked Prince Charles for help. But Charles ignored him. He still thought the main attack would come from the north.

Many of the soldiers in the first Austrian line were from Württemberg. They were Protestants, and some Austrians doubted if they would fight hard against the Protestant Prussians. They fought for a while, but then they ran away. They also caused the Bavarian soldiers to run with them.

The first wave of Prussian infantry, supported by their cannons, pushed towards Leuthen. These experienced soldiers had plenty of ammunition. They quickly overwhelmed the first Austrian line. Nádasdy sent his cavalry to stop them, but it was no use.

Prince Charles and Daun finally realized they had been tricked. They rushed troops from their right side to the left. But their battle line was now stretched out too far. As the Austrians retreated, the Prussian cannons fired at them from the side, causing even more damage.

The Prussian soldiers reached Leuthen in just 40 minutes. They pushed the Austrian troops into the village. There was fierce Hand-to-hand fighting inside Leuthen. The village was small, and soldiers were packed together, making the fighting terrible.

The Austrians briefly gained an advantage. They moved some cannons to cover their infantry. But Frederick ordered his heavy cannons on the Butterberg to fire. Some people said these cannons helped win the battle more than the infantry.

The Austrian cavalry, led by Joseph Count Lucchesi d’ Averna, tried to attack the Prussian infantry from the side. This could have changed the battle. But 40 squadrons of Zieten's Prussian cavalry attacked them from one side. Another 30 squadrons attacked from the front. Lucchesi was killed, and his cavalry was scattered. The cavalry fight caused even more confusion among the Austrian infantry. Overwhelmed, the Austrian soldiers broke and ran. They retreated towards Breslau.

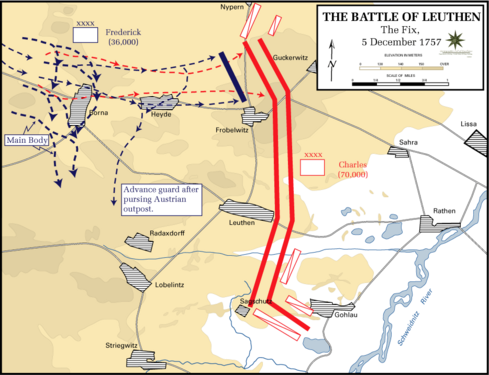

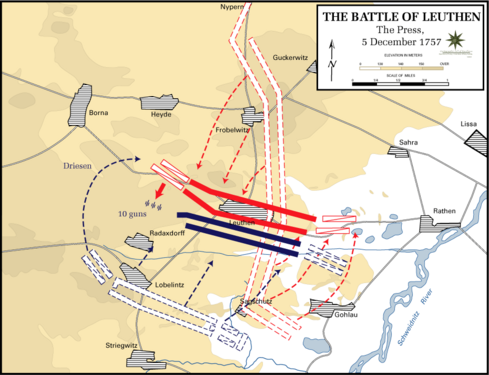

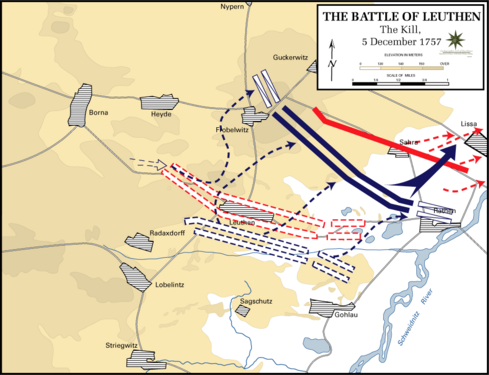

Maps

Solid red lines indicate Habsburg positions. Solid blue lines indicate Prussian positions. Dotted lines show movement. Rectangles with a diagonal line indicate cavalry.

- The Battle in Four Maps

What Happened After the Battle

As the fighting ended, snow began to fall. Frederick stopped his army from chasing the Austrians. Some soldiers started singing a famous song, Nun danket alle Gott (Now Thank We All Our God). It's said the whole army joined in, but this might be a legend.

Frederick went to the town of Lissa. He found the castle courtyard full of surprised Austrian officers. He politely asked them, "Good evening, Gentlemen, I dare say you did not expect me here. Can one get a night's lodging along with you?"

After a day of rest, Frederick sent half his cavalry to chase the retreating Austrian army. They captured another 2,000 men. With the rest of his army, Frederick marched on Breslau. By chasing the main Austrian army away, the Prussians isolated the Austrian soldiers still in Breslau. The Austrian general in charge of Breslau had about 17,000 French and Austrian soldiers. Breslau was a strong city with walls. The Austrians wanted to hold it because it had many supplies. On December 7, Frederick began to attack the city. Breslau surrendered by December 19–20.

Who Won and Who Lost

The Austrians had about 66,000 soldiers. They lost 22,000 men. This included 3,000 killed, 7,000 wounded, and an amazing 12,000 captured. The Prussians also captured 51 flags and 116 of the 250 Austrian cannons.

The Prussian army had 36,000 soldiers. They lost 6,344 men. This included 1,141 killed, 5,118 wounded, and 85 captured. They did not lose any cannons.

This battle was a huge blow to Austrian morale. Their army, twice the size of the Prussians, was completely beaten. Prince Charles and Daun were very sad. Charles had often struggled against Frederick before, but never this badly. After this defeat, Maria Theresa replaced Prince Charles with Daun. Charles then retired from military service. The Austrians learned an important lesson: don't fight the Prussians in open fields.

Why Frederick Won

Frederick won because the Austrians made mistakes.

- First, Prince Charles only saw what he expected to see. He didn't use his light cavalry to scout and find out what the Prussians were really doing. Frederick later said that just one patrol could have found out his whole plan.

- Second, the Austrians didn't put out guards on their unprotected left side. This was a big mistake for an experienced officer like Nádasdy.

- Third, even when the attack started on his left, Prince Charles was still focused on the fake attack on his right. By the time he ordered troops to move, they had too far to go.

Leuthen was Frederick's greatest victory. It showed how good the Prussian infantry was. In one day, Frederick got back everything the Austrians had won earlier that year. The battle became a perfect example of how to use 18th-century battle tactics.

Frederick had learned from earlier battles where his soldiers ran out of ammunition. At Leuthen, ammunition wagons moved with the advancing soldiers. This meant troops could get more bullets quickly without stopping. The Prussian cavalry also did a great job protecting the sides of the infantry. They also made important charges that broke up Austrian attempts to regroup. Frederick's "flying artillery" (cannons that could move quickly) also kept up with the army. Their loud 12-pounder cannons, called Brummers, also helped Prussian morale and scared the Austrians.

This victory changed how Frederick's enemies saw him. Before, they often spoke badly about him. But after Leuthen, he was widely called the King of Prussia. The victories at Leuthen and Rossbach probably saved Prussia from being conquered by Austria. Fifty years later, Napoleon called Leuthen "a masterpiece of movements, maneuvers and resolution."

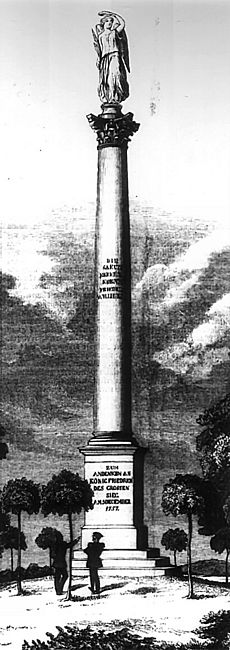

Memorials

A memorial was built in 1854 to honor the Prussian army at Leuthen. Frederick's great-great nephew, King Frederick William IV, ordered a victory column. It had a golden goddess of victory on top. The monument was 20 meters (66 feet) tall. During or after World War II, soldiers destroyed the monument. Only parts of its base remain today.

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |