Battle of Rossbach facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Rossbach |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Third Silesian War | |||||||

Battle of Rossbach, unknown artist |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 22,000 79 guns |

41,110 114 guns |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 169 killed 379 wounded |

8,000–10,000 killed, wounded and captured | ||||||

The Battle of Rossbach was a major fight during the Seven Years' War. It happened on November 5, 1757, near the village of Rossbach in Saxony. This battle is famous because Frederick the Great, the King of Prussia, won a huge victory.

Frederick's Prussian army had about 22,000 soldiers. They faced a much larger army of 41,110 men. This Allied army was made up of soldiers from France and the Holy Roman Empire. Even though he was outnumbered, Frederick defeated them in just 90 minutes!

The Battle of Rossbach was a turning point in the Seven Years' War. France decided not to send troops against Prussia again. Also, Britain saw how strong Prussia was and gave Frederick more money to help him. After this battle, Frederick quickly marched to Breslau. There, he used similar tactics to win another big battle against the Austrian army at Leuthen.

Many people consider Rossbach one of Frederick's best military plans. He beat an enemy army twice his size with very few losses. His fast-moving artillery and well-trained cavalry were key to his success.

Contents

Why the Seven Years' War Started

The Seven Years' War was a global conflict, but it was especially intense in Europe. It followed another war called the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748). That earlier war ended with a treaty that didn't really solve anything.

Frederick II of Prussia, also known as Frederick the Great, had gained a rich area called Silesia. But he wanted more land from Saxony. Meanwhile, Empress Maria Theresa of Austria wanted to get Silesia back and become more powerful in the Holy Roman Empire.

By 1754, tensions grew between Britain and France in North America. Maria Theresa saw this as a chance to regain her lost lands. France also wanted to challenge Britain's control of trade. So, France and Austria, who used to be enemies, became allies.

Britain's King George II then allied with his nephew, Frederick, and Prussia. This alliance also included areas like Hanover. These big political changes were called the Diplomatic Revolution.

Europe in 1757

At the start of the war, Frederick had one of the best armies in Europe. His soldiers could fire their muskets very quickly. They could also march long distances and perform complex movements on the battlefield.

Frederick first took over Saxony. Then he fought in Bohemia, winning the Battle of Prague in May 1757. But after the Battle of Kolín, things got tough. His fast-moving war turned into a slow, tiring one.

By summer 1757, Prussia was in trouble from two sides.

- To the east, Russian forces attacked Memel with 75,000 troops. After a few days, they captured it. The Russians then invaded East Prussia and won the Battle of Gross-Jägersdorf. However, they couldn't capture Königsberg, the capital, because they ran out of supplies. Supplying a large army far from home was a big problem for the Russians. This forced Frederick to stop his invasion of Bohemia and pull back.

- In Saxony and Silesia, Austrian forces started taking back land from Frederick. In September, at the Battle of Moys, the Austrians defeated the Prussians. Frederick's trusted general, Hans Karl von Winterfeldt, was killed.

As summer ended, a combined French and Imperial Army (Reichsarmee) moved from the west. Their goal was to meet up with the main Austrian army near Breslau. Prince Soubise and Prince Joseph of Saxe-Hildburghausen led this Allied force.

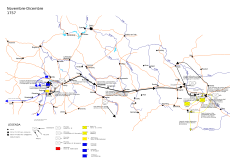

If these enemy armies joined, Prussia would be in a very bad spot. Frederick knew this. He used a clever strategy called "interior lines." This meant he marched his army quickly between the enemy forces. He covered 274 km (170 mi) in just 13 days! To do this, he left his supply wagons behind and got supplies ahead of his army.

Frederick tried to force the Allies into a battle, but they kept moving away. For several days, both sides tried to outmaneuver each other. During this time, Austrian raiders even attacked Berlin and almost captured the Prussian royal family.

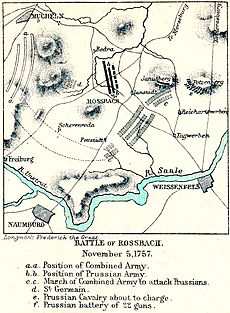

The Battlefield and Movements

The Battle of Rossbach wasn't just about the 90 minutes of fighting. It was also about the five days of careful movements leading up to it. The land played a big role in these movements.

The area around Rossbach was a wide plain with small hills. These hills were not very high, but they made it hard for horses pulling cannons to move. There were also sandy and marshy areas. A small stream ran near Rossbach.

On October 24, 1757, Prussian Field Marshal James Keith was in Leipzig. The Imperial Army had taken over Weissenfels. Frederick joined Keith two days later. Other Prussian generals and their troops also arrived. By October 28, Frederick had 22,000 men.

On October 30, Frederick led his army out of Leipzig. He sent a special unit ahead to clear the way. The next day, Frederick moved towards Weissenfels in heavy rain. The French soldiers there were completely surprised when the Prussians arrived. The French tried to defend the town, but the Prussians quickly broke through. The French then burned the bridge over the Saale river to stop the Prussians from following. About 630 French soldiers were trapped and surrendered.

While the armies exchanged cannon fire, Frederick sent scouts to find another way to cross the Saale river. The Allies had a good position to watch Frederick's moves. But then, for some reason, the Allied commanders moved back. They didn't know what Frederick was planning.

By November 3, Frederick's engineers had built new bridges, and the whole Prussian army crossed the river. Frederick then sent 1,500 cavalry (horse soldiers) under Friedrich Wilhelm von Seydlitz to raid the Allied camp. This surprise raid made the Allied commanders move to a safer spot. On November 4, Frederick set up his camp at Rossbach.

The Allied officers were frustrated by their leaders' caution. They knew Frederick was outnumbered. One officer convinced Prince Soubise that they should attack Frederick's left side and cut off his escape route. So, they decided to attack the next morning.

The Battle Begins

Setting the Stage

On the morning of November 5, 1757, the Prussian camp was between Rossbach and Bedra. The Allied army was to the west. The Allies had twice as many soldiers as the Prussians. Their advanced troops could see Frederick's entire camp.

The Allied army had 41,110 men, including 31,000 infantry (foot soldiers) and 10,000 cavalry. They also had 109 cannons. The Allied commanders decided to attack. They started moving after 11:00 a.m. Their plan was to march around Frederick's left side and then attack him from the north. This would cut off his escape route. To do this, they had to march across the front of the Prussian army, which was risky.

Frederick watched the French from a rooftop in Rossbach. At first, he thought the Allies were retreating. But then he saw their columns turning east. He realized their plan: to attack his side and rear, and cut off his communication lines. Frederick decided to fight right away.

Frederick's Clever Plan

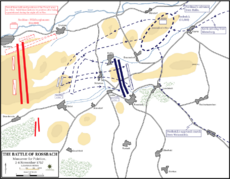

By 2:30 p.m., Frederick understood the Allied plan. By 3:00 p.m., the Prussian army quickly packed up their camp and got ready to fight.

Friedrich Wilhelm von Seydlitz took his 38 squadrons of cavalry and moved them behind two small hills, the Janus and Pölzen. This hid their movement from the enemy. Colonel Karl Friedrich von Moller followed with 18 cannons, setting them up behind the Janus hill. A few Prussian cavalry units stayed in Rossbach to keep an eye on the Allied advanced troops.

The Allied commanders thought the Prussians were running away. They ordered their advanced troops to rush forward. The Allied infantry marched in long columns. They didn't send out scouts or an advanced guard. They marched blindly into Frederick's trap.

The Trap Closes

When the Prussians left their camp, they left a few light troops to make it look like they were still there. Frederick didn't plan to form a line facing the enemy or to retreat. His army could move twice as fast as the Allies. If the Allies had already formed their battle line, Frederick would hit their right side. If they were still marching in columns, he would crush the front of their columns before the rest could get ready.

The Allies marched in two main columns. They tried a complicated turn to the east. This was hard to do with so many soldiers, especially on uneven ground. Some of their reserve troops got mixed up between the main columns, blocking their own cannons. Also, soldiers on the outside of the turn couldn't keep up.

The Allied commanders ignored the confusion. They thought the Prussians were retreating. They hurried their march, sending their cavalry forward. This made their columns even more disorganized.

At 3:15 p.m., Moller's artillery on Janus hill opened fire on the confused Allied soldiers. The Allied cavalry, which was ahead of their own infantry, was hit hard. But the Allied commanders still thought Frederick was retreating. They brought up some of their own cannons, but the Prussian fire was too strong. The Allied cavalry tried to get out of range, which made their infantry lines even more messy.

Meanwhile, Seydlitz had gathered his cavalry into two lines behind the Pölzen hill. They waited hidden. When the Allied cavalry came close, Seydlitz gave the signal to charge. At 3:30 p.m., Seydlitz's 20 squadrons of cavalry burst over the hill and crashed into the Allied army. The Prussian attack broke through the disorganized Allied lines. The fighting became hand-to-hand. Seydlitz himself was wounded. He then sent in his remaining 18 squadrons. This second charge hit the French cavalry from the side.

The fighting moved quickly past the Allied infantry. The Allied reserve troops were trying to get organized, but the Prussian cavalry pulled them into the fight. The Allied reserve cannons were useless because they were stuck in the middle of their own infantry.

The Prussian infantry, led by Prince Henry, waited in a special formation. Any Allied units that escaped the artillery and cavalry ran right into a hail of musket fire from Prince Henry's men. French counterattacks failed. Many Allied cavalry units were crushed and trampled their own men trying to escape. The battlefield was covered with dead and wounded soldiers and horses. This part of the battle lasted about 30 minutes.

Seydlitz then did something unusual: he pulled his cavalry back. Normally, cavalry would chase fleeing enemies. But Seydlitz regrouped his forces behind some trees. The Allies were relieved to see the cavalry leave. They then focused on the Prussian infantry. The Allied battalions formed into columns and marched forward, ready to charge with bayonets.

As the Allies advanced, they came into range of Prince Henry's infantry. The disciplined Prussian soldiers fired volleys that tore through the Allied columns. Moller's artillery, now reinforced, also fired on them. The leading Allied ranks stopped, and the ranks behind them pushed forward. Prince Henry's infantry kept advancing and firing.

Then, Seydlitz brought his cavalry back for a final, massive attack. All 38 squadrons charged the Allied army from the side and rear. This sudden attack caused panic among the Imperial troops. Three regiments threw down their weapons and ran, and the French ran with them. Seydlitz's cavalry chased them until it was too dark to see.

After the Battle

The battle lasted less than 90 minutes. Only seven Prussian battalions fought directly, and they used very little ammunition.

The Allied commanders, Soubise and Saxe-Hildburghausen (who was wounded), managed to keep only a few regiments together. The rest of their army scattered. The French and Imperial troops lost six generals, which was very high for the time. They had about 1,000 dead and 3,500 wounded. Around 5,000 were missing or captured. Some historians say the number of captured was much higher, almost 13,800. The Prussians captured 72 cannons, seven flags, and 21 standards. They also captured eight French generals and 260 officers.

Prussian losses were very low. Frederick boasted about it. Records show about 169-170 Prussians died and 430 were wounded. This was less than 10% of the Prussian soldiers who actually fought.

Soubise often gets blamed for the loss. But his army was not the best. Many of his best troops were fighting elsewhere. His army also had many civilians following it, like chefs, tailors, and servants. After the battle, one of his generals complained that his troops were "robbers, murderers, and cowards."

The Imperial army was also not very good. Their commander said they lacked training, discipline, and leadership. These units had little experience fighting together, which caused problems during the battle. Many German soldiers in the Imperial army were also unhappy about being allied with the French.

Rossbach was important because it strengthened Prussia's alliance with Britain. Britain saw that Frederick could keep the French busy in Europe. This allowed Britain to focus on fighting France in North America.

While Frederick was fighting at Rossbach, the Austrians had been taking back Silesia. They captured Schweidnitz and then Breslau. Frederick and his 22,000 men quickly marched 274 km (170 mi) from Rossbach to Leuthen in just 12 days. There, they joined other Prussian troops. Frederick's army of 33,000 faced 66,000 Austrians. Even though his troops were tired, Frederick won another big victory at Leuthen.

What Made Rossbach a Masterpiece?

After the battle, Frederick reportedly said, "I won the battle of Rossbach with most of my infantry having their muskets shouldered." This meant that less than a quarter of his army actually fought. Frederick used clever movements and only a small part of his force—3,500 horsemen, 18 cannons, and three battalions of infantry—to defeat a much larger enemy. His tactics at Rossbach became famous in military history.

Rossbach also showed the amazing skills of two of Frederick's officers: Colonel Karl Friedrich von Moller (artillery) and General Friedrich Wilhelm von Seydlitz (cavalry). Both men had a special skill called coup d'œil militaire. This means they could quickly see the best places to position troops and how to attack the enemy. Frederick himself said this skill was key for an officer.

Seydlitz had spent years training his cavalry to be fast and powerful. Moller had developed highly mobile artillery. His artillery engineers could move their cannons quickly around the battlefield. This wasn't "flying artillery" yet, but it was a step towards it.

Moller and Seydlitz understood Frederick's overall goals. Seydlitz didn't just attack once. He pulled his cavalry back into a group of trees to regroup. When the time was right, he led them in a second, powerful attack that finished the battle. Moller's artillery waited hidden until the French were in range, then fired with great accuracy. The loud cannon fire could be heard miles away.

Rossbach proved that marching in large columns was not as good as the Prussian battle line. The big columns couldn't stand up to Moller's cannon fire or Seydlitz's cavalry charges. The bigger the enemy formation, the more losses they suffered.

The stunning victory at Rossbach changed alliances in the Seven Years' War. Britain gave Frederick more money. France lost interest in fighting Prussia after this defeat. In 1759, France reduced its support for its allies, leaving Austria to fight Prussia alone in Central Europe.

Rossbach Today

From 1865 to 1990, the area around Rossbach was used for mining. This changed the landscape a lot. Many towns were destroyed, and people had to move. The town of Rossbach itself was destroyed in 1963.

Today, most of the battlefield is farmland, vineyards, and a nature park. The old mine pit was filled with water, creating a large lake called the Geiseltal See. This lake is now a swimming and recreation area.

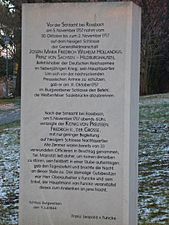

Four monuments to the battle were built in the town of Reichardtswerben. One was put up in 1766 to thank God for sparing the town. Another stone at Burgwerben castle, put up in 1844, tells the story of the battle and how Frederick the Great stayed there after his victory. A local road is even named "Von-Seydlitz-Straße" after the cavalry general.

- Memorials

- Battlefield over time

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |