Ernest Renan facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Ernest Renan

|

|

|---|---|

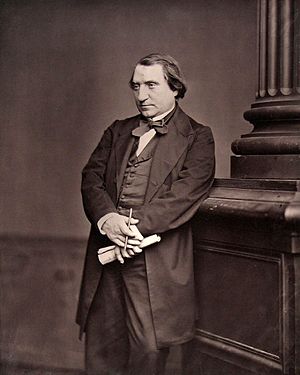

Ernest Renan by Antoine Samuel Adam-Salomon, circa 1870s

|

|

| Born |

Joseph Ernest Renan

28 February 1823 |

| Died | 2 October 1892 (aged 69) |

|

Notable work

|

Life of Jesus (1863) What Is a Nation? (1882) |

| Era | 19th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Continental philosophy |

|

Main interests

|

History of religion, philosophy of religion, political philosophy |

|

Notable ideas

|

Civic nationalism |

|

Influences

|

|

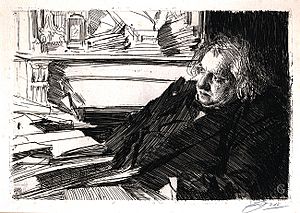

| Signature | |

Joseph Ernest Renan (born February 27, 1823 – died October 2, 1892) was a famous French thinker. He was an expert in Eastern cultures and Semitic languages. These are languages like Hebrew and Arabic. Renan was also a historian of religion, a language expert, and a philosopher. He wrote important books about the early history of Christianity. He also shared popular ideas about nationalism, which is a strong feeling of pride in one's country. Renan was one of the first to suggest the idea that Ashkenazi Jews might be descendants of the Khazars. The Khazars were a Turkic people who adopted the Jewish religion. This idea is now not believed by most scholars.

Contents

Ernest Renan's Early Life

Birth and Family Background

Ernest Renan was born in Tréguier, a town in Brittany, France. His family were fishermen. His grandfather became wealthy from fishing and bought a house in Tréguier. Ernest's father was a ship captain and believed in a republic, a type of government where citizens elect leaders. His mother came from a family who supported the king. Renan often thought about these different political ideas from his parents.

When he was five years old, his father passed away. His older sister, Henriette Renan, who was twelve years older, became very important to the family. She tried to run a school for girls in Tréguier, but it didn't work out. So, she moved to Paris to work as a teacher.

His Education and Learning

Ernest went to a church school in his hometown. His teachers said he was "obedient, patient, hardworking, careful, and thorough." While priests taught him math and Latin, his mother also helped with his education. Renan's mother was partly Breton. Her family from her father's side came from Bordeaux. Renan used to say that he felt a mix of two different personalities inside him: the "Gascon" (from Bordeaux) and the "Breton."

In the summer of 1838, Renan won many awards at his school. His sister Henriette told a doctor in Paris about her talented brother. This doctor then told Félix Dupanloup, a priest who was setting up a new church school called Saint-Nicolas-du-Chardonnet. This school aimed to educate young Catholic nobles and bright students from church schools together. Dupanloup invited Renan, who was then fifteen and had never left Brittany. Renan was amazed to learn that knowledge was not only found in the church. He started to understand what "talent" and "fame" meant. Religion seemed very different in Paris compared to Tréguier. He looked up to Abbé Dupanloup like a father.

Studying Philosophy and Languages

In 1840, Renan moved to the seminary of Issy-les-Moulineaux to study philosophy. He was very excited about Catholic teachings at first. He was interested in philosophers like Thomas Reid and Nicolas Malebranche. Later, he studied Hegel, Immanuel Kant, and Herder. Renan began to notice that the philosophy he was learning didn't always match his religious faith. But he really wanted to find true, proven facts. He wrote to Henriette, "Philosophy excites and only half satisfies the appetite for truth; I am eager for mathematics." Henriette had found a better teaching job with the Count Zamoyski family. She had a very strong influence on her brother.

Discovering Philology

It was the study of languages, called philology, that helped Renan with his doubts. In 1844, he went to the college of St Sulpice to study languages before becoming a priest. Here, he started learning Hebrew. He soon realized that different parts of the Book of Isaiah were written at different times. He also saw that the grammar and history in the Pentateuch were from later than the time of Moses. He found that the Book of Daniel was clearly written centuries after the events it described. At night, he read new novels by Victor Hugo. By day, he studied Hebrew and Syriac with Arthur-Marie Le Hir. In October 1845, Renan left St Sulpice. He felt too controlled by the church. He decided to stop his connection with religious life and became a teacher at M. Crouzet's school for boys.

Ernest Renan's Career and Ideas

Becoming a Scholar

Renan, who was taught by priests, embraced the idea of science with great enthusiasm. He was amazed by the universe. He once wrote that someone who has time to keep a diary hasn't truly understood how vast the universe is. In 1846, he learned about the certainties of science from Marcellin Berthelot, who was his student at M. Crouzet's school. They remained friends for life. Renan only worked as an usher in the evenings. During the day, he continued his research in Semitic philology. In 1847, he won the Volney prize for his book "General History of Semitic Languages." He also earned a degree as a university fellow and was offered a job at a school in Vendôme.

In 1856, Renan married Cornélie Scheffer in Paris. She was the daughter of Hendrik Scheffer and niece of Ary Scheffer, both Dutch-French painters. They had two children: Ary Renan, who became a painter, and Noémi, who married Yannis Psycharis. In 1863, the American Philosophical Society made him an international member.

The Life of Jesus Book

Renan became very famous for his book Life of Jesus (Vie de Jésus), published in 1863. He said the idea for the book came from his sister, Henriette. They were traveling in Syria and Palestine when she suddenly died from a fever. He started writing the book with only a New Testament and a copy of Josephus as his guides. The book was translated into English the same year it came out and has been printed for over 145 years.

In his book, Renan wrote that Jesus was a man, not God. He did not believe in the miracles described in the Gospels. Renan thought that by showing Jesus as a human, he was giving him more importance. This book caused a lot of debate. Many Christians were upset because it treated Jesus's life like any other historical person's life. It also suggested that the Bible should be studied like other historical documents. Some Jews were also angry because the book described Judaism as foolish and illogical, and said that Jesus and Christianity were better.

Renan's Social and Political Views

Renan was not just a scholar. In his books about St. Paul and the Apostles, he showed his interest in society and his belief in equality. In 1869, he tried to become a member of parliament for Meaux. He was becoming more open-minded. He was almost ready to accept the Empire, but he wasn't elected.

A year later, the Franco-Prussian War began. This war changed Renan's views. He had always admired Germany for its thinkers and scientists. But now, he saw Germany destroying his home country. He no longer saw Germans as scholars but as invaders.

In his book La Réforme Intellectuelle et Morale (1871), Renan tried to help France's future. He still had some German ideas. He suggested that France should have a society with a strong leader and an elite group that the rest of the country supports. He believed this would bring honor and duty. The problems of the Commune (a revolutionary government in Paris) made him even more sure of these ideas.

His later works, like Dialogues Philosophiques (1871) and Ecclesiastes (1882), show a more disappointed and doubtful side of him. He had tried to make France follow his ideas, but it didn't happen. However, as France became stronger, he started to observe the fight for justice and freedom in a democratic society with interest. In the last two volumes of his Origins of Christianity, he showed that he was okay with democracy. He believed that even big problems don't stop the slow but sure progress of the world. He also found peace with the good moral parts of Catholicism and remembered his religious youth.

What Makes a Nation?

Renan's idea of what makes a nation has been very important. He explained it in his 1882 speech, Qu'est-ce qu'une nation? ("What is a Nation?"). Some German writers, like Fichte, said a nation is based on things like race or a shared language. But Renan said a nation is formed by people who want to live together. He famously said it's about "having done great things together and wishing to do more."

He also said that a nation's existence is based on a "daily plebiscite," meaning people choose every day to be part of it. Some people criticize this idea, saying it's too ideal. They argue that Renan's ideas were actually similar to German traditions.

Karl Deutsch once suggested that a nation is "a group of people united by a mistaken view about the past and a hatred of their neighbors." This quote is often wrongly linked to Renan. However, Renan did write that for a nation to exist, people must have many things in common, but they "must also have forgotten many things." For example, he said every French citizen must have forgotten the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre and the massacres in the 13th century in the South of France.

Renan believed that "Nations are not forever. They had a beginning and they will have an end. And they will probably be replaced by a European confederation." His work has especially influenced Benedict Anderson, a scholar who studied nationalism in the 20th century.

Later Years and Works

As he grew older, Renan became more supportive of the French Third Republic. He joked that he needed about ten years to accept any government as real. He said that even though he wasn't a republican from the start, he would be more loyal to the Republic than people who had just become republicans. The progress of science and the freedom of thought under the Republic made him feel better. He disagreed with philosophers like Hippolyte Taine who believed everything was set by fate.

When he was almost sixty, in 1883, he published his autobiography, Souvenirs d'Enfance et de Jeunesse (Memories of Childhood and Youth). This book, along with Life of Jesus, is one of his most famous. It showed readers that a poetic and simple world still existed in his memories of the French coast. It has the charm of old Celtic stories and the honesty that people in the 19th century valued.

His other works, like Ecclesiastes and Drames Philosophiques, show his careful, critical, and sometimes disappointed, but still hopeful, spirit. They show how he felt about uneducated Socialism. He believed that even ordinary people, once they understood their responsibilities, could rule well. He thought that smart people could accept being less powerful if it meant more freedom for ideas. He also believed that religion and knowledge would last as long as the world itself. This showed Renan's deep belief in ideals.

Renan was a very hard worker. At sixty, after finishing Origins of Christianity, he started his History of Israel. This book was based on his lifelong study of the Old Testament. The first volume came out in 1887, and the last two were published after he died. While it had some factual errors, it was very important for understanding how religious ideas developed. It also showed a clear picture of Renan's mind.

In his last years, he received many honors. He became an administrator of the Collège de France and a grand officer of the Legion of Honor, a very high French award. More of his books and letters were published after his death.

Ernest Renan passed away in 1892 in Paris after a short illness. He was buried in the Cimetière de Montmartre.

Honors and Legacy

- A large armored ship, the Ernest Renan, launched in 1906, was named after him.

- The town of Renan, Virginia in the United States was also named in his honor.

Places to Visit

- Musée de la Vie romantique, Hôtel Scheffer-Renan, Paris – This museum has items related to Renan and his family.

Ernest Renan's Books

- (1848). On the Origin of Language.

- (1852). Averroës and Averroism.

- (1855). General History and Comparative Systems of Semitic Languages.

- (1857). Studies in Religious History.

- (1863–1881). History of the Origins of Christianity:

- (1863). Life of Jesus.

- (1866). The Apostles.

- (1869). Saint Paul.

- (1873). The Antichrist.

- (1877). The Gospels and the Second Christian Generation.

- (1879). The Christian Church.

- (1882). Marcus Aurelius and the End of the Ancient World.

- (1871). The Intellectual and Moral Reform of France.

- (1882). What is a Nation?

- (1883). Memories of Childhood and Youth.

- (1887–1893). History of the People of Israel [5 volumes].

- (1890). The Future of Science, Thoughts from 1848.

See also

In Spanish: Ernest Renan para niños

In Spanish: Ernest Renan para niños

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |