Benedict Anderson facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Benedict Anderson

|

|

|---|---|

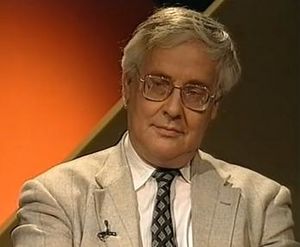

Anderson in a 1994 interview

|

|

| Born |

Benedict Richard O'Gorman Anderson

August 26, 1936 |

| Died | December 13, 2015 (aged 79) Batu, East Java, Indonesia

|

| Citizenship | Ireland |

| Alma mater | King's College, Cambridge (BA) Cornell University (PhD) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Political science, historical science |

| Institutions | Cornell University (Professor Emeritus) |

| Doctoral advisor | George McTurnan Kahin |

| Doctoral students | John Sidel |

| Notes | |

|

Brother of Perry Anderson

|

|

Benedict Richard O'Gorman Anderson (born August 26, 1936 – died December 13, 2015) was an important historian and expert in political science. He was born in China but lived and taught in the United States. Anderson is most famous for his 1983 book, Imagined Communities. In this book, he explored how nationalism began and grew around the world. He was very interested in Southeast Asia and spoke many languages. He taught at Cornell University. Anderson's work on the "Cornell Paper" questioned the official story of major political changes in Indonesia in the 1960s. This led to him being asked to leave that country for many years. Benedict Anderson was the older brother of another historian, Perry Anderson.

Contents

About Benedict Anderson

Early Life and Education

Benedict Anderson was born on August 26, 1936, in Kunming, China. His father was Anglo-Irish, and his mother was English. His family moved to California in 1941 to avoid the Japanese during the Second Sino-Japanese War. Then, in 1945, they moved to Ireland.

Anderson went to Eton College, a famous school in England. Later, he studied at King's College, Cambridge University. While at Cambridge, he became interested in fighting against imperialism. This means he was against one country controlling another. This idea influenced his later work as a Marxist and anti-colonialist thinker.

Studying Southeast Asia

After finishing his degree at Cambridge in 1957, Anderson went to Cornell University in the United States. There, he focused his research on Indonesia. He earned his PhD in government studies in 1967. His main teacher at Cornell was George McTurnan Kahin, a well-known expert on Southeast Asia.

In 1965, there were major political changes and violence in Indonesia. This led to Suharto becoming the leader. Anderson was deeply affected by these events. While still a student, he secretly co-wrote a report called the "Cornell Paper" with Ruth T. McVey. This paper challenged the Indonesian government's official story about the events of 1965. Many people in Indonesia who disagreed with the government shared this paper widely.

Because of his actions, Anderson was not allowed to enter Indonesia from 1972 until 1998. This ban ended when Suharto stepped down from power.

Anderson could speak many languages important to his studies, including Indonesian, Javanese, Thai, and Tagalog. He also spoke major European languages. After the Vietnam War, he started to study how nationalism began. He also continued to explore the connection between language and power.

Anderson taught at Cornell University until he retired in 2002. After retiring, he spent most of his time traveling in Southeast Asia. He passed away in his sleep on December 13, 2015, in Batu, Indonesia.

What are Imagined Communities?

Benedict Anderson is most famous for his 1983 book, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. In this book, he looked at how nationalism led to the creation of nations. He called these "imagined communities."

Understanding "Imagined Communities"

When Anderson used the term "imagined community", he didn't mean that a nation is fake. Instead, he meant that any group of people so large that its members don't know each other personally must "imagine" themselves as part of the same group. For example, you will never meet everyone in your country, but you still feel like you belong to that country.

Anderson believed that earlier thinkers didn't fully understand how powerful nationalism was. He pointed out that nationalism didn't have its own "grand thinkers" like other big ideas.

Puzzles of Nationalism

Anderson started his book by talking about three puzzles of nationalism:

- New but feels old: Nationalism is a fairly new idea, but people often think their nation has existed forever.

- Everyone belongs, but each is unique: Everyone belongs to a nation, but each nation seems completely different from others.

- Powerful but hard to define: People are willing to die for their nations, but it's hard to explain exactly what a nation is.

Anderson suggested that nationalism appeared when people started to reject three old beliefs:

- That certain languages (like Latin) were better than others for finding universal truths.

- That rulers (like kings) had a God-given right to rule.

- That the beginning of the world and the beginning of humankind were the same.

Anderson argued that these old beliefs began to change in Western Europe during the Age of Enlightenment. This was due to things like new economic ideas, the scientific revolution, and the invention of the printing press. He called the spread of printed materials under capitalism "print capitalism".

How Printing Helped Nationalism Grow

Anderson believed that the printing press and the mass production of books and newspapers were very important for nationalism. He said that the "revolutionary push of capitalism" helped create imagined communities.

Here's how:

- Shared Language: Printing helped make languages more stable. Certain dialects became "languages of power." For example, the language used in printed materials became the standard language for education.

- Feeling Connected: The printing press made it possible for many people to feel connected, even if they didn't know each other. Reading the same newspapers and books made people feel like they were part of a shared community. They imagined themselves living in the same time and place, united by a common language.

This shared experience created a "deep horizontal comradeship." Even though it was built on an "imagined" connection, it was very real and strong. This helps explain why people are willing to fight and even die for their countries.

Empires and Nations

Anderson also looked at how large empires with many different language groups changed in the 1800s. He called this process "official nationalism." Before, the power of kings and queens in empires had nothing to do with being part of a nation. But after World War I, many empires like the Austro-Hungarian, German, Ottoman, and Russian empires broke apart. The nation state became the normal way to organize countries. For example, leaders at the League of Nations after the war presented themselves as representatives of nations, not empires.

Selected Works

- Some Aspects of Indonesian Politics under the Japanese Occupation: 1944–1945 (1961)

- Mythology and the Tolerance of the Javanese (1965)

- Java in a Time of Revolution; Occupation and Resistance, 1944–1946 (1972)

- A Preliminary Analysis of the 1 October 1965, Coup in Indonesia (1971) (With Ruth T. McVey)

- "Withdrawal Symptoms" (1976)

- Religion and Social Ethos in Indonesia (1977)

- Interpreting Indonesian Politics: Thirteen Contributions to the Debate (1982)

- Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (1983; second edition, 1991 and later printings)

- In the Mirror: Literature and Politics in Siam in the American Era (1985)

- Language and Power: Exploring Political Cultures in Indonesia (1990)

- The Spectre of Comparisons: Nationalism, Southeast Asia, and the World (1998)

- "Petrus Dadi Ratu" (2000)

- Violence and the State in Suharto's Indonesia (2001)

- Western Nationalism and Eastern Nationalism: Is there a difference that matters? (2001)

- Debating World Literature (2004)

- "In the world-shadow of Bismarck and Nobel" (2004)

- Under Three Flags: Anarchism and the Anti-Colonial Imagination (2005)

- Why Counting Counts: A Study of Forms of Consciousness and Problems of Language in Noli me Tangere and El Filibusterismo (2008)

- The Fate of Rural Hell: Asceticism and Desire in Buddhist Thailand (2012)

- A Life Beyond Boundaries: A Memoir (2016)

Honors and Awards

Benedict Anderson received many awards for his important work:

- Association for Asian Studies (AAS), 1998 Award for Distinguished Contributions to Asian Studies.

- Guggenheim Fellowship, 1982 for his work in political science.

- Fukuoka Prize, 2000 Academic Prize.

- Membership to the American Philosophical Society.

- Social Science Research Council, 2011 Albert O. Hirschman Prize.

- Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia, Economic and Social Science Prize at the 1st Annual Asia Cosmopolitan Awards.

See also

In Spanish: Benedict Anderson para niños

In Spanish: Benedict Anderson para niños