Maurice Barrès facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Maurice Barrès

|

|

|---|---|

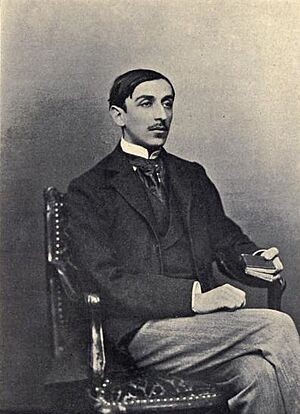

Barrès in 1923

|

|

| Born | Auguste-Maurice Barrès 19 August 1862 Charmes, Vosges, France |

| Died | 4 December 1923 (aged 61) Neuilly-sur-Seine, Paris, France |

| Occupation | Journalist, novelist, politician |

| Literary movement |

|

Auguste-Maurice Barrès (born August 19, 1862 – died December 4, 1923) was a famous French writer, journalist, and politician. He became well-known in French literature after publishing his book The Cult of the Self in 1888. In politics, he was first elected to the French Parliament (called the Chamber of Deputies) in 1889. He remained an important political figure for the rest of his life.

Barrès was part of a literary style called Symbolism. This style focused on using symbols and ideas rather than direct descriptions. His early books, like The Cult of the Self, explored a love for oneself and even some mystical ideas. Later, during the Dreyfus affair (a big political scandal in France), his ideas changed. He moved from believing in individual freedom to focusing more on the importance of the nation and its traditions. He also helped make the word nationalisme popular to describe his strong belief in his country.

In politics, he joined groups like the Ligue des Patriotes (League of Patriots) and became its leader in 1914. Barrès was friends with Charles Maurras, who started a royalist party called Action Française. Even though Barrès stayed a republican (meaning he believed in a government led by elected officials, not a king), he greatly influenced many French royalists and other thinkers. During World War I, he strongly supported the Union Sacrée, a political agreement to unite all parties for the war effort. Later in life, Barrès returned to the Catholic faith. He worked to help restore old French churches and helped make June 24 a national day to remember St. Joan of Arc.

Contents

Biography

Early Life and Writings

Maurice Barrès was born in Charmes, France. He went to school in Nancy, where he studied law. In 1883, he moved to Paris to continue his studies. There, he met writers and artists who were part of the Symbolist movement. He even met the famous writer Victor Hugo. Barrès started writing for a magazine and then created his own, though it only lasted a few months.

He later moved to Italy, where he wrote Sous l'œil des barbares (1888). This was the first book in his famous series called Le Culte du moi (The Cult of the Self). This series explored self-love and the enjoyment of senses. His early books were known for their detailed and sometimes complex writing style.

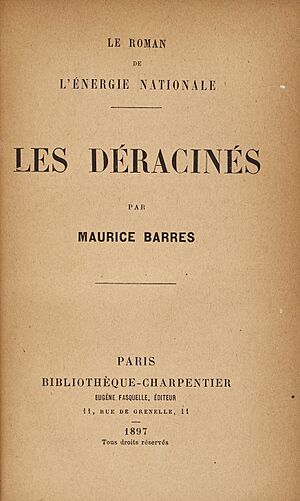

In 1894, a play he wrote was performed at the Comédie Française, a famous French theater. A few years later, in 1897, he started another important series called Le Roman de l'énergie nationale (Novel of the National Energy). The first book in this series was Les Déracinés (The Uprooted). In this new series, he moved away from focusing only on himself. Instead, he wrote about being loyal to his country and the idea that a nation is like a living body.

During the Dreyfus affair, Barrès sided with those who were against Alfred Dreyfus. This event pushed his political views further to the right. He began to focus on a type of nationalism that valued the land and the history of a place, often called "earth and the dead."

The Roman de l'énergie nationale series promoted love for one's local area, military strength, loyalty to one's roots and family, and keeping the unique qualities of old French regions. Les Déracinés tells the story of seven young people from Lorraine who go to Paris to find success. Other works by Barrès include:

- Scènes et doctrines du nationalisme (1902)

- Les Amitiés françaises (1903), which encouraged teaching patriotism through studying national history

- Au service de l'Allemagne (1905), about an Alsatian soldier in a German army

In 1906, Barrès was elected to the Académie française, a very respected French institution for arts and literature. He had tried before but finally succeeded. In his later years, he returned to the Catholic faith. He started a campaign in a newspaper to help restore churches in France. His son, Philippe Barrès, also became a journalist.

Political Actions

When he was young, Barrès brought his ideas about the importance of the individual into politics. He strongly supported General Boulanger, a popular political figure. Barrès ran a newspaper that supported Boulanger in Nancy. In 1889, at just 27 years old, he was elected to Parliament. His political goals were "Nationalism, Protectionism, and Socialism." He kept his seat until 1893.

However, during the Dreyfus affair, Barrès shifted his political views to the right. He became a leading voice against Alfred Dreyfus. He believed Dreyfus was guilty based on his ideas about race.

In 1894, he started a short-lived magazine called La Cocarde. This magazine aimed to bring together different political ideas, from the far-left to the far-right. It was nationalist, against the current parliament, and against foreigners. It had many different writers, including monarchists, socialists, and anarchists.

Barrès was elected to Parliament again in 1906, representing the Seine region, and stayed in this role until he died. He was part of a conservative political group. In 1908, he disagreed with his friend and political opponent Jean Jaurès about honoring the writer Émile Zola. Despite their differences, Barrès was one of the first to show respect when Jaurès was assassinated just before World War I.

During World War I, Barrès was a strong supporter of the Union Sacrée, which meant all political parties worked together for the war. He was sometimes called the "nightingale of bloodshed" because of his support for the war. However, his private notes show that he wasn't always as optimistic as he seemed in public. During the war, he also recognized the contributions of French Jews, seeing them as an important part of the "national genius."

After World War I, Barrès wanted Luxembourg to become part of France. He also wanted France to have more influence in the Rhineland region. In 1920, the French Parliament passed his idea to make June 24 a national day to remember Joan of Arc.

Nationalism

Barrès is seen as one of the main thinkers of ethnic nationalism in France around the early 1900s. This idea focused on the importance of shared heritage and culture for a nation. He was also linked to Revanchism, which was the desire to get back the Alsace-Lorraine region that Germany had taken after the 1871 Franco-Prussian War. In fact, he helped make the word "nationalism" popular in France.

Barrès believed that a nation was not just created by people agreeing to a social contract. Instead, he thought a nation was built on its history, land, and traditions, passed down from "the dead" (ancestors). He believed that individuals were less important than society as a whole.

Barrès worried about different groups mixing in modern cities like Paris. He thought this could harm the unity of the nation. He believed the nation should balance local loyalties (to family, village, region) with loyalty to the whole country. He supported a strong leader and direct democracy, where people vote on laws directly. He also thought that being against Jewish people could help unite a right-wing political movement.

It's important to know that Maurice Barrès never used the exact phrase "le grand remplacement" (the great replacement). However, he did express the idea that French national identity was being harmed by immigration from certain ethnic groups.

Love for Spain

Barrès was very fond of Spain. He saw it as a passionate and unique country, describing it as "an Africa leaving your soul with a sort of furor so fast as chilli does in your mouth." He was interested in the "South" and "Orient" and highlighted the period when Moors ruled Spain. He visited Spain several times, especially Toledo, and wrote about his experiences there.

Dada and Barrès

In 1921, a group of artists called the Dadaists held a pretend trial for Barrès. They accused him of "attacking the safety of the mind" and sentenced him to 20 years of hard labor. This fake trial was also a sign of the Dada movement breaking up.

Final Years and Death

Barrès published a book called Un jardin sur l'Oronte (A Garden on the Orontes) in 1922. This book caused some debate because it mixed religious and non-religious themes in a way that surprised some Catholic readers.

Maurice Barrès passed away in Neuilly-sur-Seine on December 4, 1923.

Works in English translation

- The Undying Spirit of France, Yale University Press, 1917.

- "Young Soldiers of France". In The War and the Spirit of Youth, Atlantic Monthly Company, 1917.

- Colette Baudoche: The Story of a Young Girl of Metz, George H. Doran Company, 1918.

- "Officers and Gentlemen", The Atlantic Monthly, Vol. CXXI, 1918.

- The Faith of France, Houghton Mifflin & Company, 1918.

- The Sacred Hill, The Macaulay Company, 1929.

- "Uprooted". In The World's Greatest Books, W. H. Wise & Co., 1941.

Other

- Massia Bibikoff, Our Indians at Marseilles, with an Introduction by Maurice Barrès, Smith, Elder and Company, 1915.

- Georges Lafond, Covered with Mud and Glory, with a Preface by Maurice Barrès, Small, Maynard & Company, 1918.

In foreign languages

- René Jacquet (1900). Notre Maître Maurice Barrès, Librairie Nilsson.

- J. Ernest Charles (1907). La Carrière de Maurice Barrès, Académicien, E. Sansot & Cie.

- René Gillouin (1907). Maurice Barrès, E. Sansot & Cie.

- Henri Massis (1909). La Pensée de Maurice Barrès, Mercure de France.

- Nicolas Beauduin (1910). "L'Evolution de Maurice Barrès", Quelques Uns, No. 1.

- Jean Herluison (1911). Maurice Barrès et le Problème de l'Ordre, Nouvelle Librairie Nationale.

- Jacques Jary (1912). Essai sur l'Art et la Psychologie de Maurice Barrès, Emile-Paul.

- Paul Bourget (1924). La Leçon de Barrès, À la Cité des Livres.

- François Mauriac (1945). La Rencontre avec Barrès, La Table Ronde.

- Albert Garreau (1945). Barrès, Défenseur de la Civilisation, Éditions des Loisirs.

- Sarah Vajda (2000). Maurice Barrès, Flammarion.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Maurice Barrès para niños

In Spanish: Maurice Barrès para niños

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |