Carlism in literature facts for kids

The Carlists were a political movement in Spain that supported a different branch of the royal family for the throne. They believed in traditional values, the Catholic Church, and often wanted to keep old local laws (called fueros). The Carlists fought several wars in the 1800s, known as the Carlist Wars. These wars and the ideas of Carlism had a big impact on Spanish literature, inspiring many writers to create poems, plays, and novels.

In 1890, a famous writer named Miguel de Unamuno gave a talk about how Carlism was used in literature. For many years, Carlism had been a popular topic in Spanish writing. It was a time when many important Spanish books featured Carlist themes. Later, Carlism became less popular in literature, sometimes only used in stories during the time of Francoism (a period of dictatorship in Spain). Today, Carlism in literature often provides a historical or romantic setting for stories.

Contents

Romanticism and the Carlist Wars

The First Carlist War began when Romanticism, a style of art and literature focusing on emotions and individualism, was very popular in Spain. Writers quickly reacted to the conflict. Their main goals were to spread their side's message and describe events as they happened. Poetry and drama were the first types of literature to respond to the war.

Drama: Plays About the War

When the First Carlist War started in 1833, plays were quickly written about it. Many of these plays were performed to gather support for either side. Most plays were against the Carlists, because the government (called the Cristinos) controlled the cities where theaters were. These plays were often short, one-act pieces with strong messages and clear heroes or villains.

Some writers created satires, which are plays that make fun of people or ideas. Jose Robreño y Tort was known for his anti-Carlist satires. Another writer, Manuel Bretón de los Herreros, wrote a comedy called El plan de un drama (1835) against the Carlists. Other plays were set in history but still promoted Liberal ideas, often against the Inquisition (a historical religious court) or absolute rule. Examples include El trovador by Antonio García Gutiérrez (1836) and Carlos II el Hechizado by Antonio Gil y Zárate (1837), which was very popular.

The Carlist side also had writers, but their plays are less known. José Vicente Álvarez Perera, a Carlist official, wrote works like Calendario del año de 1823.

Poetry: Rhymes of Conflict

Poets also quickly wrote about the war. Many poems were published in newspapers. A historian gathered 110 works from this time, mostly written to spread propaganda. None of these poems are considered major works of Spanish poetry today. They included odes, sonnets, and epics, covering themes like battles, peace, and foreign involvement.

Many poets wrote for the Cristino side. José de Espronceda wrote a strong anti-Carlist poem called Guerra (1835), ending with "death to the Carlists!" Other poets included Juan Arolas and Ramón de Campoamor. Some poems focused on specific events, like the Convention of Vergara (a peace agreement) or the battle of Luchana. Francisco Navarro Villoslada wrote about Luchana, portraying Carlists as fanatics. However, he later changed his views and supported Traditionalism.

Some poems from this time even shed light on the origins of words, like "guiri", a term used by Carlists to insult their opponents.

Prose: Novels Emerge

Prose, especially novels, was slower to feature the Carlist theme. Early works like those by Mariano José de Larra were a mix of short stories and satirical pamphlets. The first clear novel about the war was Eduardo o la guerra civil en las provincias de Aragón y Valencia by Francisco Brotons (1840), which showed the Cristino side.

Other novels followed, some supporting the Carlists, like Los solitarios (1843), and others strongly against them, like Espartero by Ildefonso Bermejo (1845-1846). Wenceslao Ayguals de Izco wrote important anti-Carlist novels, especially Cabrera, El Tigre del Maestrazgo (1846-1848), which was a personal revenge story by the author.

The Carlists had fewer novels defending their cause. Francisco Navarro Villoslada, after changing his views, wrote popular historical novels that showed a general Traditionalist perspective, even if not directly about Carlism. El orgullo y el amor by Manuel Ibo Alfaro (1855) is one of the few novels that clearly praised Carlism.

Realism: Carlism in the Spotlight

Realism, a literary movement that focused on showing life as it truly was, shifted the focus from poetry and drama to novels. The novel became the main way to discuss Carlism. Like in the Romantic period, literature was a battleground between Carlists and Liberals, with Liberals often having the upper hand. Galdós, a major Spanish writer, was the first to put Carlism at the center of his stories, shaping how Carlists were seen for many years.

Early Realist Works

Some writers, like Fernán Caballero, bridged the gap between Romanticism and Realism. Manuel Tamayo y Baus, a playwright, was very popular in the 1850s and 1860s. He joined the Carlists later and his plays often showed conservative Catholic views against Liberalism.

The first novel clearly in the Realism style about Carlism was El patriarca del valle (1862) by Patricio de la Escosura. This novel used new realist techniques but still presented Carlists as hypocrites and cruel people. It was quite popular in the 1860s. Other novels like Matilde o el Angel de Valde Real by Faustina Sáez de Melgar (1863) and Ellos y nosotros by Sabino de Goicoechea (1867) also appeared. Antonio de Trueba included Carlism in his novels and short stories, often showing a more balanced view, though he still saw Carlist and traditional local laws (fueros) as separate.

The Third Carlist War also sparked some international interest. Ernesto il disingannato (1873-1874) by an Italian author supported the Carlist cause. Karl May, a German writer, wrote Der Gitano. Ein Abenteuer unter den Carlisten (1875), where Carlists were portrayed as harsh and wild.

Novels: Realism, Naturalism, and Manners

After the Third Carlist War, the image of Carlists as cruel and fanatic people, controlled by tricky clergy, became stronger in novels. The novel became the main literary weapon, especially in historical novels and "novels of manners" (which describe social customs).

Historical novels like Rosa Samaniego o la sima de Igúzquiza by Pedro Escamilla (1877) focused on the brutal actions of Carlist commanders. La sima de Igúzquiza by Alejandro Sawa (1888) took this brutality to even more extreme, naturalistic levels, aiming to shock readers with horrors.

Novels of manners also touched on Carlism. Marta y María by Armando Palacio Valdés (1883) used Carlist sympathies to show religious fanaticism in one character. La Regenta by Clarín (1884-1885), a very popular novel, showed Carlist supporters as fanatics who were rich and influential.

However, a few novelists showed a different view. José María de Pereda and Emilia Pardo Bazán showed understanding for their Carlist characters, even if they were minor figures. Pereda's Peñas arriba (1895) is sometimes seen as having a "Carlist thesis" or viewpoint.

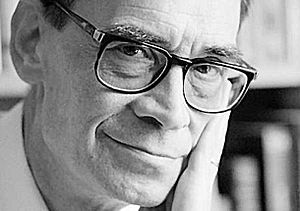

Galdós: Shaping the Carlist Image

Benito Pérez Galdós was one of the first great Spanish writers to make Carlism a central theme in his works. His famous series of historical novels, Episodios nacionales, covered the Carlist Wars. Galdós aimed to teach his fellow Spaniards about their past. He was a strong Liberal and wanted to show the harm Carlism had done to the nation. His writings greatly influenced how Carlism was seen for generations.

Many scholars believe Galdós's view of Carlism was consistent: a dangerous force that had to be defeated. His novel Doña Perfecta (1876) is a good example of his strong anti-Carlist stance. However, some argue that his view changed over time, especially after Spain's defeat in the Spanish-American War. In later Episodios Nacionales volumes, Carlism was sometimes shown in less extreme terms, and some Carlist characters, like the one in Zumalacárregui (1898), were even presented as role models.

The Carlist Voice in Literature

The Third Carlist War also led to some cultural responses, especially in the Basque language. Jacinto Verdaguer Santaló, a famous Catalan poet and Carlist supporter, wrote poems praising Carlism in Catalan. Evaristo Martelo Paumán wrote strong Carlist poems in Galician.

In prose, there were fewer Carlist authors. Ceferino Suárez Bravo's Guerra sin cuartel (1885) was a strong praise of Carlism and won an award. Manuel Polo y Peyrolón wrote several novels that subtly or openly promoted Carlism. His best work, Los Mayos (1878), was a rural love story praising loyalty. Later, he wrote Pacorro (1905) and El guerrillero (1906), which directly compared Liberal and Carlist characters or told adventure stories from the Carlist side.

In drama, Leandro Ángel Herrero was one of the few Carlist voices. A local Carlist, Carlos María Barberán, wrote stories and poems, and an unpublished play called Los Macabeos (before 1891) honoring people who defended their religious identity.

Modernism: Carlism as a Historical Shadow

In the Modernist period, Carlism was no longer seen as a direct threat. Writers could explore it differently. For them, Carlism was a fading part of the past, but one that still influenced Spanish identity and the human condition. This was also a time when Carlism was very popular among major Spanish writers.

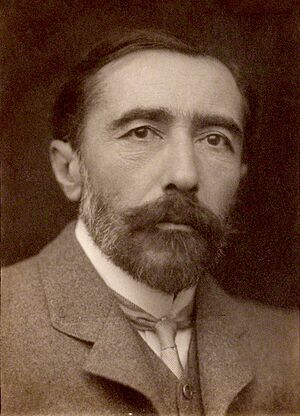

Unamuno: Two Carlisms

Miguel de Unamuno, a key figure of the Generación de 1898 (a group of Spanish writers), was one of the first to address Carlism in his novel Paz en la guerra (1897). This novel, along with others like Baroja's Zalacaín el aventurero, is one of the most famous literary works about Carlism. Unamuno's view was complex. Some believe he had sympathy for Carlism as a form of regional identity.

The common view is that Unamuno saw two types of Carlism. One was a true, unconscious Carlism rooted in rural people, like the deep, silent currents of the ocean. The other was an ideological Carlism, created by educated people, like the noisy waves on the surface. Both types of Carlism appear in Paz en la guerra, sometimes confusing characters and readers. Unamuno was initially accused of supporting Carlism, which he denied. He saw Carlism as part of a process to form Spain's national identity. The idea that "both sides were right and neither was right" is often linked to Unamuno.

Valle-Inclán: Grandeur and Irony

Valle-Inclán was another important writer of the Generation of '98 who often featured Carlism in his novels, including the Sonatas series (1902–1905) and La Guerra Carlista trilogy (1908–1909). There's debate about whether his portrayal of Carlism was genuine praise or ironic. Some say he was a true Carlist, while others point to his changing political views and believe Carlism was just one of many "masks" he wore.

In his literature, Carlism might represent historical grandeur, tradition, and heroism, contrasting with the narrow-mindedness of the middle class. Or, it might be an ambiguous myth, sometimes even a joke, used to discuss Spanish history where glory mixes with absurdity. His Carlism could be about irony, caricature, and parody. His main Carlist character, Marqués de Bradomín, is a unique kind of Carlist.

Baroja: Hostility and Adventure

Pío Baroja had the most personal experience with Carlism among the Modernist giants, from his childhood during the siege of Donostia. Carlism is a key theme in some of his works, most famously Zalacaín el aventurero (1908). Baroja was generally hostile to Carlism, seeing it as a movement of the weak, influenced by the Church.

In Baroja's novels, Carlist characters are rarely people who joined out of strong belief. They are often adventurers, criminals, fanatics, or people seeking personal revenge. While Baroja was drawn to what he saw as the authentic strength of rural Carlists, he believed it existed despite, not because of, their Carlist nature. His hero, Zalacaín, is a man of action who outsmarts and defeats the Carlists. Baroja often showed Carlists as cowardly and brutal, not as strong fighters.

Other Modernist Writers

Vicente Blasco Ibañez, another writer of the Generation of '98, fought Carlists in real life and only occasionally included them in his novels. In La catedral (1903), Carlists are shown as hypocrites who commit bad deeds in the name of God.

The true Carlist literary voice was rarely heard during this time. Antonio de Valbuena wrote "novels of edification" (stories meant to teach morals). Domingo Cirici Ventalló wrote political fantasy novels that attacked Liberal ideas from a Carlist viewpoint.

In Catalan, Marian Vayreda i Vila wrote short stories like Recorts de la darrera carlinada (1898) and the masterpiece novel La Punyalada (1904). Both are set in a Carlist environment, but their message is complex, sometimes seen as a discussion about the very nature of Carlism.

In poetry, Ignacio Baleztena Ascárate wrote Spanish lyrics for the Carlist anthem Oriamendi in 1908. Other Carlist poets included Pilar de Cavia and Florentino Soria López. In drama, Eduard Genovès i Olmos wrote a Valencian play called Comandant per capità (1915).

Foreign authors also showed interest. Ego te absolvo (1905), sometimes attributed to Oscar Wilde, showed a Carlist as brutal and wild, reflecting a common Spanish stereotype that crossed borders.

Catastrophism: Decline and War Literature

The 20th century in Spanish literature is hard to define, but this period, sometimes called "catastrophism," focused on the breakdown of old structures and instability. Interest in Carlism in literature declined significantly during the time of Primo de Rivera's dictatorship and the Second Spanish Republic. However, the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) briefly brought Carlism back into literature to rally support for the fighting sides.

Interwar Novels: Big Names and Others

Baroja continued to write about Carlism in his later novels, keeping his earlier style. Miguel de Unamuno mostly stopped writing about Carlism in his fiction. Valle-Inclán's later works, like El ruedo ibérico (1927-1932), showed Carlism in an increasingly exaggerated and comical way, with his main character eventually leaving the Carlist cause.

Joseph Conrad, a Polish-English writer, featured Carlism as a background in his novel The Arrow of Gold (1919), creating an atmosphere of mystery. Graham Greene, another English writer, set his novel Rumour at Nightfall (1931) during the First Carlist War, using Carlism to explore moral dilemmas related to religious devotion.

Among French writers, Pierre Benoit's Pour don Carlos (1920) clearly supported the Carlist cause and was popular enough to be made into a movie.

In Spain, Gabriel Miró's novels, like Nuestro Padre San Daniel (1921), sometimes featured Carlist characters who were more complex and mysterious than usual. Estanislao Rico Ariza, a Carlist who fought anarchists, wrote Memorias de un terrorista (1924) based on his experiences. Benjamin Jarnés wrote Zumalacárregui, el caudillo romántico (1931), portraying the Carlist general as a brilliant individual.

Writers who opposed Carlism included Félix Urabayen, who showed Carlists as hypocrites in his novels set in Navarre. Pere Coromines also wrote against Carlism, though he preferred a Carlist victory over the continuation of the corrupt monarchy at the time. Manuel Azaña, a future prime minister, saw Carlism as a dying relic of old Spain in his novel Fresdeval (1931).

Drama and Poetry in the Interwar Years

Drama became less important as a political battleground. However, some plays during the 1920s and 1930s included Carlist themes. Manuel Azaña's La corona (1931) featured a Traditionalist character who leads a coup. Carlist-written plays were less popular, often staged in local Carlist clubs or religious places. Manuel Vidal Rodríguez wrote religious dramas with historical settings. La amazona de Estella (1926) by José del Rio Sainz was a poem-play honoring Carlism.

In poetry, Cristóbal Botella y Serra published in Integrist (a strict Catholic Carlist group) newspapers. Florentino Soria López also wrote poetry with clear political sympathies. José Pascual de Liñán y Eguizábal, an older Carlist leader, wrote classic verses praising Spanish virtues and Carlist heroes. José María Hinojosa Lasarte, a young Carlist leader, also contributed to surrealist poetry, though not with Carlist themes.

Literature of the Civil War (1936-1939)

The Spanish Civil War led to many literary works aimed at mobilizing support. While Republican literature was less common, the Nationalist side produced at least 10 novels featuring Carlists as main characters. These novels were often simple, with clear moral messages, and aimed to glorify Carlism. This surge of pro-Carlist novels was short-lived. After 1937, literature increasingly had to fit the official propaganda, which only allowed Carlist themes if they blended with the new unified party, FET.

El teniente Arizcun by Jorge Claramunt (1937) is considered a typical Carlist war novel. Other examples include La Rosa del Maestrazgo (1939) by Concepción Castella de Zavala and La ciudad sitiada (1939) by Jesús Evaristo Casariego, which strongly praised Carlism. La enfermera de Ondárroa by Jorge Villarín (1938) focused on a female character who dies with a Carlist cry. A children's version of wartime literature was the Carlist magazine Pelayos.

The Spanish Civil War also inspired many foreign authors, but most ignored Carlist themes. Ernest Hemingway's famous novel For Whom the Bell Tolls (1940) only briefly mentions Carlists, showing some compassion for them. A French novel, Requeté by Lucien Maulvault (1937), stood out for its psychological depth and tragic view of the civil war.

Francoism: Carlism in the Past

During the Francoism period (the dictatorship after the Civil War), Carlism in literature was treated in a specific way. It was welcomed when shown as a glorious movement from the past, but not as a current cultural idea. The best-selling novel about the Civil War, Un millón de muertos by José María Gironella (1961), presented Carlists in a mixed way.

Novels with a Message

In the first decades after the war, novels continued the wartime style, but this trend faded by the 1950s. These novels had strong moral messages, simple characters, and predictable plots. As the Falange party gained power, their historical view became dominant, pushing Carlist characters into secondary roles. This is seen in works by Rafael García Serrano.

Some authors, like Eladio Esparza, wrote novels that praised general Traditionalism, which was the root of Carlism, rather than Carlism itself. Jaime del Burgo wrote novels like Huracán (1943) and Lo que buscamos (1951), which showed patriotism but also a sense of sadness. La casa by Dolores Baleztena (1955) followed a Navarrese family who kept their traditional values. The last novel of this type was ¡Llevaban su sangre! by Francisco López Sanz (1966), which was very strong in its political views.

Adventure Novels

Another type of novel focused on adventure, often set in historical times, especially the 19th-century Carlist Wars. This allowed Carlist authors more freedom to promote their political ideas, as censorship was stricter for the recent Civil War. This type of literature grew from the 1940s and became a main way to keep Carlism present in culture during Francoism.

Many Carlist authors wrote adventure novels. Jesús Evaristo Casariego and Antonio Pérez de Olaguer were among them. However, two very productive female Carlist authors excelled in this genre: Concepción Castella de Zavala (about 15 novels) and Carmela Gutiérrez de Gambra (writing as Miguel Arazuri, about 40 works). Their novels, for a popular audience, featured adventurous or romantic plots with Carlists often as main characters. Gutiérrez de Gambra believed that simple, popular novels were better for spreading Carlist ideas than complex literary works.

Poets of the Era

In poetry, José Bernabé Oliva and Manuel García-Sañudo wrote about traditional themes. Antonio Sánchez Maurandi and Germán Raguán (known for his collection Montejurra (1957)) wrote poetry that directly praised Carlism. Ignacio Romero Raizábal became the most famous Carlist writer of the Franco era, publishing novels and poems until the early 1970s.

Martin Garrido Hernando, a Carlist volunteer in the Civil War, wrote a poem called Soneto a los Caídos (Sonnet to the Fallen), a lament for the Carlist and Nationalist dead. This poem, with music, is now performed at military funerals, though some of its original lyrics have been changed.

Rafael Montesinos, who volunteered for the Carlists as a teenager, became a rising star in poetry. His poems, published from the 1940s, were not explicitly Carlist but showed irony and melancholy. He was also known for starting and leading weekly poetry sessions in Madrid, which continued after Francoism.

Contemporary Literature: Carlism as a Setting

After Franco's dictatorship ended, Spanish culture changed. In contemporary literature, Carlism mostly serves two purposes. The main one is to provide a setting for adventure stories, often mixed with history, psychology, romance, or fantasy. These stories are usually set in the 19th century. The other, less common, purpose is to use Carlism in broader discussions about Spanish identity, often from a democratic and tolerant viewpoint, focusing on the 20th century. In neither case is Carlism the central focus.

Youth Literature

Carlism is very popular as a setting for adventure novels for young readers, sometimes called "juvenile literature." These novels continue the adventure style of the Franco era but are more complex and no longer contain hidden Carlist messages. They praise general values like friendship, loyalty, and courage, and often show the absurdity of civil wars. They are typically set in the 19th century, as the last civil war is still considered too sensitive a topic for this type of literature.

Many novels fit this genre. Early examples include El capitán Aldama by Eloy Landaluce Montalbán (1975) and Un viaje a España by Carlos Pujol (1983). Later, different types emerged: adventure stories like El cementerio de los ingleses by José María Mendiola Insausti (1994) and El oro de los carlistas by Juan Bas (2001). There are also educational books for children like Las guerras de Diego by Jordi Sierra i Fabra (2009), gothic stories, alternative history, and romances.

One novel that clearly shows Carlist support is Ignacio María Pérez, acérrimo carlista, y los suyos by Maria Luz Gomez (2017), which follows a Carlist family through six generations. Outside Spain, Carlism is rarely a literary theme, with a few exceptions like The Flame is Green by R.A. Lafferty (1971).

Historical Novels

Some novels focus heavily on historical details and figures, using Carlism as a backdrop for historical analysis rather than just adventure. Galcerán, el héroe de la guerra negra by Jaume Cabré Fabré (1978) and La filla del capità Groc by Víctor Amela (2016) are examples, focusing on Carlist commanders.

Many novels focus on Ramón Cabrera, a famous Carlist general. El tigre rojo by Carlos Domingo (1990) praises him as a free man. El rey del Maestrazgo by Fernando Martínez Lainez (2005) and El invierno del tigre by Andreu Carranza (2006) focus on his later life and psychology. La bala que mató al general by Ascensión Badiola (2011) is about Zumalacárregui. Interestingly, none of the Carlist claimants (the people who wanted to be king) have attracted much attention from modern authors.

Noticias de la Segúnda Guerra Carlista by Pablo Antoñana (1990) is an epic novel that explores the idea of two Carlisms: a popular one and an elite one. It also presents a sad view of civil war as a constant part of Spanish history. La flor de la Argoma by Toti Martínez de Lezea (2008) is a symbolic story about the extremes of ideology.

Literature on the 1936-1939 Civil War

The Spanish Civil War is a very popular topic in contemporary Spanish prose. Thousands of related fiction books have been published. Many of them only mention Carlism briefly to add realism. Even Camilo José Cela, a Nobel Prize winner, barely mentions Carlism in his Civil War novel Mazurca para dos muertos.

However, a few novels give Carlism a more important role. Herrumbrosas lanzas by Juan Benet (1983) is a large novel with many comments on Carlism. Poliedroaren hostoak by Joan Mari Irigoien Aranberri (1983), written in Basque, tells the story of the Basque region through two families, one Carlist and one Liberal. Verdes valles, colinas rojas by Ramiro Pinilla (2004-2005) suggests that wars never truly end, using a Carlist priest as a key character.

El requeté que gritó Gora Euskadi by Alberto Irigoyen (2006) is about a former Carlist fighter who realizes the injustice of the war. Antzararen bidea by Jokin Muñoz (2008) is very critical of Carlism, focusing on the repression carried out by Carlists in Navarre. A significant novel is En el Requeté de Olite by Mikel Azurmendi (2016), which is the first identified novel that clearly sympathizes with a Carlist character simply for being a Carlist.

Drama and Poetry Today

The Carlist theme has almost disappeared from drama. One notable play is Carlismo y música celestial by Francisco Javier Larrainzar Andueza (1977), which presented the author's view of Carlist history. A very recent play, Bake lehorra/La paz esteril by Patxo Telleria (2022), explores responsibility and suffering during the "Basque civil war."

Jaime del Burgo, who started as a poet, returned to poetry later in life with works like Soliloquios (1998), showing sadness and bitterness. Efrain Canella Gutiérrez also wrote poetry with Traditionalist themes. El Quijote carlista is a poem that became iconic for Carlists, showing a sense of defeatism.

Rafael Montesinos continued to publish poetry after Francoism, and his weekly poetry sessions in Madrid are still held today. Luis Hernando de Larramendi, from a family of Carlist authors, published poetry with strong Traditionalist zeal, including Fronda Carlista (2010), dedicated to Carlist kings and leaders. Javier Garisoain, a Carlist leader, is also a poet whose works feature explicit Carlist themes.

Perhaps the most important poetic contribution to the Carlist cause in recent times comes from an unexpected source: José Antonio Pancorvo, a Peruvian author. His unique poetry, considered baroque and mystical, includes the volume Boinas rojas a Jerúsalem (2006), which combines his style with strong Carlist support.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Carlismo en la literatura para niños

In Spanish: Carlismo en la literatura para niños

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |