Ignacio Baleztena Ascárate facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Ignacio Baleztena Ascárate

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Ignacio Baleztena Ascárate

1 April 1887 Pamplona, Spain

|

| Died | 2 September 1972 (aged 85) Pamplona, Spain

|

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Occupation | self-government official |

| Known for | Pamplona icon |

| Political party | Traditionalist Communion |

Ignacio Baleztena Ascárate (1887–1972) was a Spanish expert in folk customs. He was also a Carlist politician and soldier. He is remembered for his love of traditional festivals and his work to preserve the culture of Navarre.

Contents

Ignacio Baleztena's Early Life

Ignacio Baleztena was born in 1887 in Pamplona, Spain. His family had strong roots in Navarre. His grandfather, José Joaquín Baleztena, was from Leitza. He owned buildings there.

Ignacio's father, Joaquín Baleztena Muñagorri, was a successful businessman. He owned land and helped start local companies. He was also a city council member in Pamplona. He was part of the Carlist movement.

Ignacio's mother, María Dolores Ascárate Echeverría, also came from a Carlist family. Her father was an officer in the First Carlist War.

Ignacio grew up in a very Catholic home with 8 siblings. His older brother, Joaquín, became a Carlist political leader. His younger sister, Dolores, was a Carlist writer. His younger brother, Pedro María, became a famous pelota player.

In 1927, Ignacio married Carmen Abarrategui Gorosábel. They had 10 children. Many of his children and grandchildren also became involved in public life. For example, his grandson Ignacio Baleztena Navarrete works for the European Union.

Ignacio's Education and Early Work

Even as a child, Ignacio was interested in public events. He helped organize village feasts in Leitza. He also created an amateur theater in his family home. There, he directed and performed plays.

He studied law at the University of Deusto in Bilbao. Later, he studied architecture in Madrid and law again in Salamanca. During his university years, he wrote stories and songs. He even started his own newspaper called El Bólido.

Ignacio returned to Pamplona in 1910. He joined Catholic groups that opposed new laws. In 1908, he wrote Spanish lyrics for "Marcha de Oriamendi". This was a traditional Carlist song.

He also started El Requeté de Pamplona, a newspaper for young Carlists. In 1911, he led the Carlist youth group, Juventud Jaimista. He focused on organizing fun events like plays and dances. From 1914 to 1918, he worked for the Spanish government in France.

Ignacio Baleztena as a Public Servant

In 1918, Ignacio was elected to the Pamplona City Council. One of his first ideas was to create Caja de Ahorros de Navarra. This bank helped people get affordable loans.

He strongly supported the traditional laws of Navarre, called fueros. He helped create groups that wanted to restore these laws. In 1921, he was elected to the Navarrese Diputación Foral, a regional government body. He served there until 1928.

Ignacio also promoted Navarrese identity through culture. He helped with religious events and historical projects. He also helped open a Navarrese section in the Museum of Bayonne.

He spent a lot of time at the Archivo General de Navarra, which is a historical archive. He became its director in the 1930s. In 1940, he founded the Museo de Recuerdos Históricos in Pamplona. This museum was a Carlist cultural center. He directed it until it closed in the 1960s. By the end of his life, he was a well-known figure in Pamplona. People affectionately called him "aitacho," which means "little father."

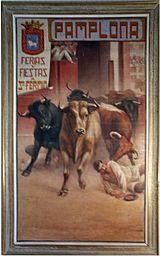

Ignacio and Pamplona's Festivals

From a young age, Ignacio loved the "Giants and Bigheads" of Pamplona. He helped design and carry these large figures. He became an expert on their history and traditions.

His interest grew to include all of Pamplona's festivals. In the 1920s, he became a key organizer. He wrote many articles about them. He didn't just keep old customs alive. He also brought back forgotten rituals and even created new ones. These included celebrations for Epiphany, Holy Week, and Corpus Christi. He also started the Procesión de San Saturnino.

Ignacio also helped revitalize local pilgrimages, like the one to Ujué. Many of these festivals had a strong religious meaning. For example, the large 1922 celebrations for San Francisco Javier. He also started the yearly pilgrimage to Javier in 1939.

He was especially fascinated by the sanfermines festival. He studied its history and was part of the Corte de San Fermín. He is known for popularizing the unofficial festival song "Uno de enero, dos de febrero".

In 1911, Ignacio and his friends first performed the "riau-riau" ritual. It's still debated if it was a Carlist protest or just a joke. He believed there should be few rules for the Running of the Bulls. However, he never ran with the bulls himself. He was a major figure in shaping the Sanfermines until the early 1960s.

Some people saw his work as a way to spread traditional values. Others saw it as a way to keep Navarre's unique identity alive.

Ignacio's Views on Basque Culture

Ignacio's first language was Spanish. He understood Basque well, but spoke it with some difficulty. Growing up in Leitza, he was very interested in Basque culture.

He opposed the new idea of Basque nationalism. Instead, he supported a traditional view of Basque identity. In 1913, he started a weekly paper called Joshe Miguel. It was meant to be a Basque "anti-nationalist" newspaper.

Ignacio joined the Sociedad de Estudios Vascos. He promoted the traditional "Euskalerria" idea of Basque identity. He was against the "Euzkadi" idea, which was more nationalist. He did not like the ikurriña (Basque flag). He preferred traditional provincial flags. He also criticized new festivals like Aberri Eguna.

In 1925, Ignacio helped create Euskeraren Adiskideak. This group promoted Basque culture in Navarre. In 1931, he started Záldiko Máldiko. This group focused on folk dances.

In 1934, this group became Muthiko Alaiak. It was a Basque cultural group known for dance and theater. It was mostly made up of Carlists. Muthiko helped spread the Traditionalist view of Navarrese society. Ignacio even used the group to playfully mock authorities.

Over time, Ignacio lost control of Muthiko. By the 1960s, the group became a center for socialist ideas. It still promotes Basque nationalism today.

Ignacio Baleztena's Political Career

Ignacio was active in Carlist youth groups from a young age. In 1919, he helped start a new Carlist weekly newspaper called Radica. He represented the Carlist movement in the Pamplona city council. In the 1920s, he was in the Diputación Foral.

During the early days of the Spanish Republic, he formed an alliance with Basque nationalists. This was before the 1931 elections. He also worked on a plan for Basque-Navarrese self-government. He initially supported it, but withdrew his support when religious issues were moved to central control.

In 1932, his family home in Pamplona was set on fire by a leftist group. In 1933, he briefly led the Navarrese Requeté, a Carlist militia.

In 1936, Ignacio helped organize Carlist support for a military coup. When the Spanish Civil War began, his family homes became important centers for the rebels. Ignacio helped organize the Tercio de San Miguel battalion. He is remembered for saving leftist supporters and prisoners during the chaos. He served as a soldier in different battalions during the war.

Ignacio did not support the unification of Carlism with Franco's Movimiento. He rejected Franco's attempts to win him over. During Second World War, the Baleztena family helped French refugees. They were against the Axis.

In the late 1940s, Ignacio and his brothers worked to rebuild Carlist groups. They were seen as leaders of the Carlists in Navarre. In 1952, Ignacio managed to publicly embarrass Franco. He sometimes had to go into hiding to avoid Falangist revenge.

The Baleztenas were against joining forces with other monarchist groups. In the mid-1950s, they criticized the Carlist leader Fal Conde. When the Huguistas appeared in the late 1950s, the Baleztenas were unsure. They supported Carlos Hugo and had good relations with the Carlist claimant Don Javier. However, they opposed the progressive Carlists when power struggles started in the mid-1960s.

Their last success was regaining control of El Pensamiento Navarro newspaper in 1970. This victory was short-lived. In the early 1970s, Ignacio was removed from the socialist-dominated Partido Carlista.

See also

In Spanish: Ignacio Baleztena para niños

In Spanish: Ignacio Baleztena para niños

- Carlism

- Joaquín Baleztena Ascárate

- Basque nationalism

- Pamplona

- Leitza

- Festivale of San Fermín

- Gigantes y cabezudos

- romeria

- Marcha de Oriamendi