José Pascual de Liñán y Eguizábal facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

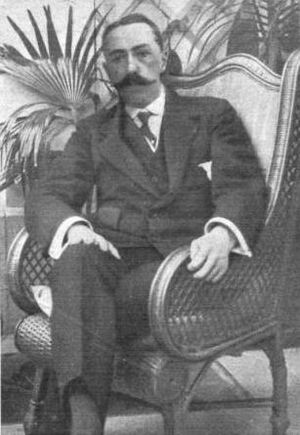

José Liñán Eguizábal

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

José Liñán Eguizábal

1858 |

| Died | 1934 (aged 75–76) |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Occupation | landowner, banker, lawyer |

| Known for | politician |

| Political party | Carlism |

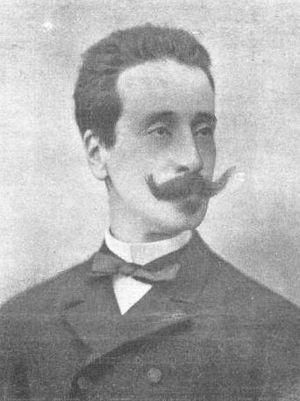

José Pascual de Liñán y Eguizábal, Count of Doña Marina (1858–1934) was a Spanish writer, newspaper manager, and a Carlist politician. Carlism was a political movement in Spain that supported a different branch of the royal family for the throne. José Liñán is best known for managing two Traditionalist newspapers in the 1890s and 1900s in the Basque Country. He also wrote some smaller works about law and history. As a politician, he briefly led the Carlist party in Castile. He is also remembered for helping to change how Carlism was seen by the public in the late 1800s.

Contents

A Look at His Family and Early Life

The Liñán family is very old in Spain. Its first known member lived in the early 1100s. Many of José Pascual's ancestors were military leaders or government workers. Some were important in the history of Spain and Latin America. One part of the family lived in southeastern Aragón, owning land in the provinces of Zaragoza and Teruel.

José Pascual's grandfather, Pascual Sebastián de Liñán y Dolz de Espejo (1775-1855), became a general during the Peninsular War. He was also a governor in New Spain (now Mexico). Later, back in Spain, he remained loyal to King Fernando VII during the First Carlist War.

José Pascual's father, Pascual de Liñán y Fernández-Rubio (1837-1920), inherited some land in Aragón. He also worked in the insurance business. He was a royal attendant and briefly served as a deputy (like a representative) for Madrid and Aragón in the Spanish parliament, called the Cortes Generales. He was part of the Conservative Party.

José Pascual's mother was María de los Dolores Eguizábal Cavanilles (died 1897). Her father, José Eugenio de Eguizábal, was an intellectual and politician. José Pascual was the older of two sons. The family lived in their properties in Aragón, Valencia, and Madrid.

José Pascual first went to school in Madrid. He was very good at history. In 1875, he began studying law and graduated in 1879. Soon after, he became a lawyer in Madrid. In 1880, he married María Josefa de Heredia y Saavedra (1860-1929) from Andalusia. Her family also had important people, including two grandfathers who were briefly prime ministers. One of them, Ángel de Saavedra, was also a famous poet.

In 1891, María Josefa inherited the title of Countess of Doña Marina. This meant José Pascual became the Count (conde-consorte) because he was her husband. They lived in Madrid and had one son, Narciso José de Liñán y Heredia. Their son later became the 3rd Count of Doña Marina and was also involved with the Carlists.

His Life as a Writer

Even as a child, José loved to write. His poem was printed in a religious magazine in 1871. As a teenager, he wrote theater reviews and poetry. He continued writing poems throughout his life, though most were for his family and friends. He published a few poems later in life, which showed his strong religious faith. Some people from other countries even thought he was "the best Spanish poet."

José Liñán also wrote academic studies, which were published in magazines or as small books. He wrote about 40 of these works, mainly focusing on law, literature, and history.

His legal studies often discussed constitutional law and had a Traditionalist point of view. He also wrote about civil law and the history of Spanish law. Most of his legal writings are now mainly important for historical reasons. However, his analysis of rules about inheritance was still used in legal discussions as late as 1966.

His historical works focused on the early modern period and were often biographies of important people. Many of these works explored his own family history. One of his works about Aragon's heraldry (family symbols) is still referenced today. He also wrote about the history of literature, focusing on specific authors.

José Liñán wrote for various newspapers and magazines throughout his life, usually contributing essays on history, literature, and religion. He used several pen names, like "E. Quis" and "Jaime de Lobera."

Managing Newspapers

José Liñán started writing for newspapers in the late 1870s. In 1887, he joined the team of La Verdad, a Traditionalist newspaper in Santander. He soon became its editor. While working there, he was attacked on the street and badly hurt, but the attackers were never found. He left La Verdad a few months later due to disagreements.

Because of his mother's family, Liñán had ties to the Basque Country, especially Bilbao. In 1888, he was invited to join El Vasco, a Traditionalist newspaper in Bilbao. In 1889, he bought the newspaper with Enrique Olea. Liñán kept the newspaper's political stance and was involved in many strong political debates. From 1890, the newspaper was called El Basco.

Running El Basco was difficult. It had only 700-900 subscribers and lost about 10,000 pesetas each year. José Liñán continued this struggle until 1897, when he left El Basco. His departure meant a change in the Carlist approach in the province, which the Carlist leader regretted.

After leaving El Basco, José Liñán started a new newspaper in San Sebastián in 1898 called El Correo de Guipúzcoa. As its director, he kept the paper's Traditionalist views. He eventually left El Correo, and the newspaper stopped publishing in the early 1910s. Some historians believe he also briefly controlled a newspaper in Toledo called El Porvenir in the late 1910s.

His Carlist Political Journey

Many of Liñán's ancestors were involved in politics, mostly on the conservative side. José Liñán seemed likely to follow a similar path. However, his maternal grandfather, José Eugenio de Eguizábal, influenced him greatly. His grandfather joined the Neo-Catholics, who were close to the Carlists. This helped shape José Liñán's political views. His maternal uncle, José Cavanilles, also supported the Carlist leader Carlos VII during the Third Carlist War.

During his time at university, Liñán joined the group around Ramón Nocedal. In 1877, he became the vice-president of the Catholic Youth in Madrid. This led him to join the Traditionalist movement at a difficult time. The Carlists had just lost a war, and many people were leaving the movement. Liñán's 1879 book of his grandfather's works was a public sign of his Traditionalist beliefs.

In the 1880s, Liñán was active in the Traditionalist movement. He wrote for various magazines, gave lectures, and took part in religious pilgrimages. He focused on religious fundamentalism rather than just supporting the royal family. When he started working for La Verdad in 1887, it seemed he was firmly on the side of the "Integrists," a strict group within Carlism. However, when the conflict within the party became open in 1888, Liñán chose to stay loyal to the Carlist leader, Don Carlos, instead of joining the Integrists. The Integrists then called him a traitor. Don Carlos, however, appreciated his loyalty.

Around 1890, Liñán became involved in the Carlist party structures in the Basque Country because of his newspaper work in Bilbao. He strongly argued for the Basque Country's Carlist organization to be independent and not controlled by the central Carlist leadership in Madrid. He also wanted local party groups to be built from the ground up, not by appointments. His efforts were partly successful in keeping the Basque-Navarrese structures independent. However, Liñán was somewhat isolated among Carlist leaders.

Supporting the Carlists from Behind the Scenes

In the early 1890s, the Carlist movement became more politically active and decided to take part in elections. Liñán, now the Count of Doña Marina, did not run for parliament himself. He did not hold any official position within the Carlist party at the provincial, regional, or national level. He preferred to attend private meetings and act as an intellectual, helping to gather support for the cause.

On the national stage, he became a theorist, writing scholarly works that promoted Traditionalist ideas. These included La Jura de los Fueros (1889), La política del rey (1891), La Unidad constitucional y los Fueros (1895), and La Soberanía del Papa (1898). In the Basque Country, as the manager of El Correo de Guipúzcoa, he supported strict Catholicism and regional traditions.

In the mid-1890s, Doña Marina became close with the new Carlist political leader, Marqués de Cerralbo. They both lived in Madrid, were from noble families, and shared interests in history, art, and writing. More importantly, they both believed that Carlism should be a "party of order." Doña Marina was a key person in promoting the new idea: "Carlism is a hope, not a fear." This was meant to change how people saw the movement, from being a group of fanatics to a respected political party. He also worked against dueling, which was unusual for someone from a group often seen as old-fashioned and quick to fight.

In 1898, Doña Marina ran for parliament for the first time. He tried to use his family's influence in the Teruel province, running in two districts. He lost in both. He tried again in 1903 but was unsuccessful. In Gipuzkoa, he focused on providing support for other Carlist candidates. Even after de Cerralbo stepped down as leader, Doña Marina remained loyal to the Carlist claimant.

His Political Peak

The 1910s were the most active period in Doña Marina's political life. He continued to work as a propagandist and theorist, becoming known as a key writer for the Carlist cause. He also regularly ran in elections for the Cortes. He ran in 1910, 1914, 1916 (though he later withdrew), and 1918. Although he never won, he became an important figure among the party's leading members.

Doña Marina began to take on major roles within the Carlist party. In the Castilian regional organization, he became the second vice-president in 1910. In the mid-1910s, he also became the head of the Madrid provincial group. Finally, in early 1918, he was named the regional leader of New Castile.

In the 1910s, Carlism faced a growing conflict between the new Carlist leader, Don Jaime, and the main party theorist, Juan Vázquez de Mella. De Mella wanted to form a broader ultra-conservative alliance. Doña Marina, who admired de Mella, tended to support him. In 1911, he suggested that Carlist leaders should lead the Catholic opposition with a more open approach. When his friend de Cerralbo became party leader again in 1913, Doña Marina became one of his closest helpers.

During World War I, Don Jaime was under house arrest in Austria, which helped de Mella and his supporters. Doña Marina tried to put the ultra-conservative alliance strategy into action in Aragón. He used his writing skills to counter propaganda that supported the Allies (the side against Germany). He argued for Spain to remain neutral, especially as the war turned against the Central Powers. Although he signed a tribute to Don Jaime in 1918, he privately felt that Don Jaime did not fully follow their Carlist beliefs. When Don Jaime reached Paris in early 1919, the conflict with the Mellistas (de Mella's supporters) grew. Don Jaime eventually regained control of the party, and de Mella and his supporters, including Doña Marina, left.

Later Years

The Mellista political plan faced its own problems. Doña Marina tended to agree with Víctor Pradera, who wanted a looser alliance based on common goals. However, Doña Marina preferred to stay in the background.

When the Primo de Rivera dictatorship began in 1923, it changed Spanish political life. Pradera joined this new system. Doña Marina was counted among the "mellistas praderistas" (Mellistas who supported Pradera). There is no clear proof that he joined the dictatorship's structures, but he did support the regime by writing newspaper articles. In 1928, Doña Marina publicly accepted Alfonso XIII as the rightful king. He argued that the king's commitment to Catholic principles made him fit to rule from a Traditionalist point of view.

Since 1911, Doña Marina was involved in a company called Sociedad Nacional de Credito. He became the president of this successful company in the late 1910s and remained in charge until the early 1930s. He was also a member of many scientific groups related to history and archaeology. People sometimes called him an "academic" or "professor," but he never actually held a university teaching job.

Liñán spent his last years at his family home in Miraflores de la Sierra, a town near the Sierra de Guadarrama mountains. After his wife died in 1929, he became almost blind. He limited his activities to a few religious organizations. In the early 1930s, he passed on the title of Count of Doña Marina to his son.

See also

In Spanish: José de Liñán para niños

In Spanish: José de Liñán para niños

| Georgia Louise Harris Brown |

| Julian Abele |

| Norma Merrick Sklarek |

| William Sidney Pittman |