Manuel Polo y Peyrolón facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

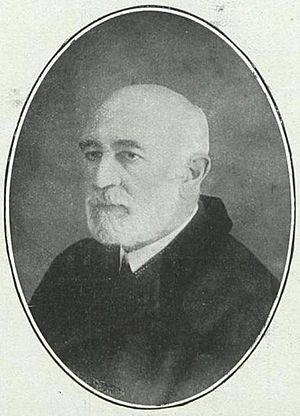

Manuel Polo y Peyrolón

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Manuel Polo y Peyrolón

1846 Cañete, Spain

|

| Died | 1918 (aged 71–72) Valencia, Spain

|

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Occupation | scholar |

| Known for | novelist |

| Political party | Partido Carlista |

Manuel Polo y Peyrolón (1846–1918) was an important Spanish writer, thinker, teacher, and politician. He is most famous for his five novels. These books mixed romantic and realistic styles, often showing everyday life and customs.

As a philosopher, he followed a Catholic way of thinking called neo-Thomism. He often disagreed with other ideas like Krausism, which was popular among liberals. In education, he strongly supported Catholic teachings. He was a leading voice against the liberal ideas of his time. In politics, he was active in Carlism, a traditionalist movement. He served in the Spanish parliament as a deputy and later as a senator.

Contents

Early Life and Family Background

We don't know much about Manuel Polo y Peyrolón's very early family history. His father, Domingo Polo y Polo, came from a town near Valencia. Domingo worked as a property registrar. He also helped start a Carlist newspaper called La Esperanza. During the First Carlist War, his father supported the Carlist side. After they lost, he had to leave his job.

Domingo settled in Cañete, a village in the mountains. This area was part of what was known as Alto Maestrazgo. Manuel's mother, María Peyrolón Lapuerta, was from a region called Aragón. Manuel's parents had at least two sons, Manuel and Florentino. Sadly, María died in 1853 when Manuel was young.

Around the mid-1850s, Manuel's father became very ill. He promised to dedicate his life to God if he recovered. He later became a friar, which is a type of religious brother.

From the mid-1850s, Manuel and his younger brother were cared for by their aunt. Manuel spent most of his childhood in Gea de Albarracín. He considered this area his "little homeland." He grew up in a very Catholic home. He learned traditional political ideas from his father. His first books were Carlist stories and magazines.

After his early schooling, he went to college in Valencia. He studied philosophy, literature, and law. He later earned a PhD in philosophy. In 1870, he started teaching psychology, logic, and ethics in Teruel. Manuel Polo y Peyrolón never married or had children.

Manuel Polo as a Novelist

Manuel Polo's first book was a collection of short stories published in 1873. It showed what his later works would be like. His stories had traditional themes and a simple plot. They also had a clear teaching purpose. He set his stories in the countryside of Sierra de Albarracín. He paid close attention to local customs, almost like a study of culture.

His first novel, Los Mayos (1878), was a rural love story. It praised loyalty and faithfulness. Many people consider it his best work. It was even translated into Italian and German. His next novels, Sacramento y concubinato (1884) and Quién mal anda, ¿cómo acaba? (1890), had a stronger message. They were against liberal and non-religious ways of life.

Pacorro (1905) compared a young liberal's actions with a young Carlist's good qualities. It was set during a difficult time in Spain (1868–1876). His last major novel, El guerrillero (1906), was more of an adventure story. It was based on his brother Florentino's memories from the Third Carlist War.

People who shared his traditional views liked Polo's books. These included famous writers like Emilia Pardo Bazán. A conservative magazine praised his writing. They called him a "restorer of the Castilian novel." They liked his realistic style, which they saw as a good alternative to other popular styles.

However, Polo's books were not popular for very long. Even in the early 1900s, he was rarely mentioned by historians of Spanish literature. Today, he is mostly forgotten. His novels are seen as having simple plots. They often have too much moralizing. But they are also valued for their detailed descriptions of customs and daily life. He is also known for adding new ways of telling stories. He was one of the most important writers who supported Carlism in literature.

Scholar and Philosopher Manuel Polo

Polo taught psychology, logic, and ethics for nine years in Teruel. Because of his Carlist beliefs, he faced problems. So, he moved to Valencia in 1879. He continued teaching the same subjects there until the early 1900s. He was a member of several important academic groups. In 1908, he became a member of the Royal Academy of History.

While in Valencia, Polo wrote textbooks for philosophy students. These included Elementos de psicología (1879) and Elementos de Ética (1880). His books were used in other schools across Spain. He didn't create new philosophical ideas himself. Instead, he focused on challenging liberal ideas in education. He especially disagreed with Krausism and Darwinism. His ideas are often called neo-Thomist or "neocatholic."

Polo strongly disagreed with Krausism. This was a philosophical movement that influenced liberal Spanish politics. He believed that Catholic values were essential for public education. He was known as a "great enemy of Krausist barbarism." Even so, some scholars believe he was open to including some liberal ideas in education.

Polo also had strong views on evolutionism. Some people saw his views as old-fashioned. They thought he was against scientific progress. Others believe his approach was more balanced. They say he tried to find a way for his Catholic beliefs to fit with scientific discoveries. While his attacks on Darwinism were strong, some argue they were in line with the scientific discussions of his time. He wasn't just trying to stop evolution theory. He was trying to protect the Spanish Catholic way of thinking from secular ideas that used evolution as an argument.

Manuel Polo's Political Career

Polo started his political journey in 1870. He gave speeches at local meetings. During the Third Carlist War, he supported the Carlist rebels. He was watched by the police, and some of his property was taken away. He even had to hide for a while. Even after the Carlists lost in 1876, he faced problems at his teaching job.

In the 1880s, he helped the Carlist cause through his novels. He showed his characters having Carlist virtues. As a professor, he criticized liberal ideas. He ran for parliament in 1891 and 1893 but lost. He finally won in 1896. In parliament, he focused on education. He opposed liberal plans to make schools less religious. He also supported teaching local languages.

After losing some elections, he returned to parliament as a senator in 1907. He was re-elected in 1910 and 1914. In the Senate, he continued to defend the Catholic Church. He was known as a tough opponent. He often criticized others for not sticking to the party's beliefs. However, he also had secret talks with conservative politicians.

In the 1890s, Polo became a key Carlist leader in Valencia. He became friends with important national leaders. He even met Carlos VII, the Carlist claimant to the throne. He was considered for Carlos VII's personal secretary in 1901. He was interested in helping workers. He helped write the official Carlist program. He also convinced the claimant to reorganize the party. He believed in having strong party structures.

In 1904, Polo was made the head of the Carlist branch in Valencia. He was a very firm leader. This sometimes caused problems with other leaders. He was very strict in his beliefs. This helped prevent the party from joining other groups. On the national level, his relationships with other Carlist leaders also became difficult. This included his relationship with Carlos VII and his wife. He resigned from his leadership role, thinking it was just a formality. He was surprised when his resignation was accepted. However, as a senator, he was still appointed to the national executive committee in 1912.

Manuel Polo y Peyrolón had no close family. He spent his later years surrounded by books. He was working on his large collection of memories. He became known as a "grumpy old man." He grew very pessimistic about the future of Traditionalism. He was very doubtful of the political leaders and the Carlist claimant himself. He remained loyal to the Carlist royal family until his death.

Works

Carlism and Politics

- Ligera exposición doctrinal del credo católico tradicionalista (1892)

- Credo y Programa del Partido Carlista (1905)

- Anarquía fiera y mansa: folleto antiterrorista (1908)

- Memorias políticas (1870-1913)

Catholicism and Ethics

- Elementos de ética o filosofía moral (1882)

- León XIII y los católicos españoles (1883)

- Ética elemental (1883)

- Vida de León XIII: extracto de sus principales documentos públicos y relación de sus fiestas jubilares (1888)

- La Madre de Don Carlos. Estudio crítico-biográfico (1906)

Law and Science

- Contra Darwin: supuesto parentesco entre el hombre y el mono (1881)

- Elementos de psicología (1889)

- Lógica elemental (1902)

- La enseñanza española ante la ley y el sentido común: cuestiones pedagógicas (1908)

- Rudimentos del derecho (1911)

Novels and Tales

- Costumbres populares de la Sierra de Albarracín: cuentos originales (1876)

- Los Mayos: novela original de costumbres populares de la Sierra de Albarracín (1879)

- Sacramento y concubinato: novela de costumbres contemporáneas (1884)

- Quien mal anda, ¿cómo acaba? (1890)

- Manojico de cuentos (1895)

- Pepinillos en vinagre (1891)

- El guerrillero: novela tejida con retazos de la historia militar carlista (1906)

See also

In Spanish: Manuel Polo y Peyrolón para niños

In Spanish: Manuel Polo y Peyrolón para niños