End of Basque home rule in Spain facts for kids

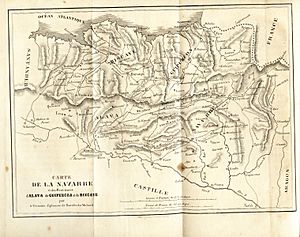

The end of Basque home rule or fueros in Spain was a big change that happened between the First Carlist War (1833-1840) and after the Third Carlist War (1876-1878). For many centuries, the different Basque territories had a special status. They were like their own mini-countries, but they were also loyal to the Crown of Castile. This period brought that special status to an end. In the French Basque Country, home rule was suddenly stopped during the French Revolution (starting 1790).

After losing their home rule (fueros), the Basque Economic Agreement (1878) was created. This led to a time of uneasy peace, with some local uprisings like the Gamazada in Navarre. It also saw the start of Basque nationalism, a movement for Basque identity and rights.

Contents

Why Home Rule Changed

After King Ferdinand VII returned in 1814, Basque laws and institutions were brought back. But the Spanish government still wanted more control. In 1829, Navarre's parliament (called Cortes) met for the last time.

In 1833, a new liberal government took power in Madrid. They wanted to make all of Spain's laws and government the same. This led to the First Carlist War. In 1837, Spain passed a new constitution. This new law ignored the special laws and ways of governing that the Basques had.

Basque Home Rule Changes

The Embrace of Bergara was an agreement that ended the First Carlist War in the Basque Country. General Baldomero Espartero promised to tell the Spanish government to respect Basque laws. However, the government in Madrid was mostly made up of liberals who didn't like Basque home rule.

So, when they approved the agreement in October 1839, they added a phrase: "with due regard to the constitutional unity of the Monarchy." This changed the original agreement.

The Minister of Justice, Lorenzo de Arrazola, said this phrase meant "unity in all the big bonds." But it also meant that a Spanish government official, called a governmental deputy, would be placed in each Basque area. This made many pro-fueros people upset. They felt it went against the very idea of Basque self-government.

Between the Wars

In February 1840, the Basque areas of Biscay, Gipuzkoa, and Álava refused to accept any changes to their self-government. But Navarre was different. Its Provincial Council sent a team to Madrid to negotiate based on the October 1839 Act.

Many people in Navarre didn't want to negotiate their self-government. But others, like Yanguas y Miranda, thought Navarre's main law, the Fuero General, was old-fashioned. A list of six points was put together for discussion.

However, by May 1840, General Espartero became the head of the government. He worked with the Spanish Progressives. The talks with Navarre didn't go well. The result was that Navarre became like a regular Spanish province in August 1841. It kept only a few special rights, like managing its own taxes. Navarre was no longer a kingdom. This new agreement was called the Ley Paccionada or 'Compromise Act'.

Home Rule Abolished During Military Rule

The Basque Provinces were surprised by what happened to Navarre. They stopped their talks with Madrid. After the August 1841 Act for Navarre, tensions grew. The Basque regional councils strongly defended their home rule. In response, Espartero's government sent troops to the Basque Country.

In October 1841, a decree was issued in Vitoria-Gasteiz, which was occupied by the Spanish army. This decree moved customs borders to the Pyrenees mountains and the coast. This meant goods coming into the Basque Country from outside Spain would be taxed by Spain. San Sebastián and Pasaia were also declared ports for foreign trade.

In January 1842, more changes were made. Administration, justice, and government in the Basque areas became exactly like those in other Spanish provinces. The 1839 Act and the peace agreement from the war lost all their meaning. The Basque General Councils resisted these changes quietly. They held onto their own institutions, money, and special rules for military service, meaning they didn't serve in the Spanish military.

The "New Home Rule" Period

The problems of 1841 ended when Ramón María Narváez and his moderate Conservatives came to power in Spain. In July 1844, they created a new legal plan. It gave the Basque areas some limited but important self-government, similar to their old system.

Álava, Gipuzkoa, and Biscay entered a difficult period called "a peculiar neoforal period." For almost 30 years, Basque authorities didn't demand full independence. Instead, they kept an uneasy peace by making deals with the Spanish government. These deals were about things like how much tax they would pay and who would serve in the military, for example, during the African war campaign (1859-60).

Loss of Home Rule After War

Carlist War in the Basque Country

In 1872, war broke out in the Basque areas because Spain was unstable. An agreement was made in 1872, called the Convention of Amorebieta, between Biscayan leaders and Spanish General Francisco Serrano. But the agreement didn't last, and fighting started again.

| "The Basque Provinces and Navarre share the same history and tradition, personality and landscape, customs and believes, feelings and interests. Their territories show one and the same appearance. The Basque language, their original and main language treasured by them since always, will be kept for ever in this country as a glorious blazon for the Basque-language people [pueblo euscaro]." |

| Provincial Council of Navarre, 18 August 1866 |

Carlos, who wanted to be king, first refused to swear an oath to the fueros in Gernika. But he did so in 1874 because he worried about the loyalty of the Basques. The Carlist forces were strong in the countryside. However, they couldn't capture the main cities, which had strong Spanish military bases and liberal business owners. These business owners generally supported the fueros.

In spring 1875, the supporters of Alfonso XII tried to make a deal with the Carlists. They recognized the special Basque legal system. But Carlist officials rejected it.

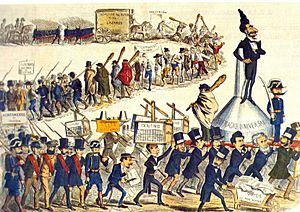

After the Carlists were defeated in Catalonia in summer 1875, Alfonso XII's Spanish forces moved north into the Basque Country. By February 1876, they controlled all Carlist areas. A huge army occupied Pamplona, and 40,000 soldiers stayed in the Basque Provinces. Martial law was put in place. The Carlist defeat meant the end of the long-standing Basque self-government.

Negotiations and Abolition

Despite the military victory, the Spanish prime minister, Canovas del Castillo, had to talk with the Basque Provinces in May 1876. These talks were held secretly with high-ranking officials from the regional councils. These officials were Liberals who wanted to keep the "7-centuries long" home rule. Canovas, however, said that the fueros were just "privileges granted by the Spanish monarchs."

After many heated discussions, no agreement was reached. On July 21, 1876, a law abolished Basque home rule. There was a strong feeling against the Basque special status in Spain. Frustrated, the Basque members of parliament in Madrid, all Liberals, left their seats in protest.

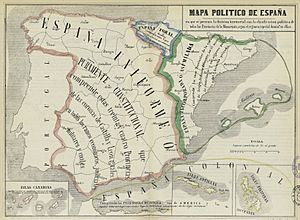

The law, pushed by Prime Minister Antonio Canovas del Castillo, ended the Basque system in Biscay, Álava, and Gipuzkoa. It made them almost the same as Navarre, which had changed in 1841. Canovas called the Abolition Act "a punishment law." He said it would bring "the expansion of the Spanish constitutional union to all Spain," following the centralist Constitution proclaimed in 1876. A single, central government was set up in Spain, based on a Spanish-Castilian model. However, the law still allowed some room for future changes. The first part of the July 21, 1876 law stated:

The duties the political Constitution has always imposed upon all the Spanish to do the military service when they are called by law, and contribute in proportion of their assets to the state expenditures, hereby expand to the inhabitants of the provinces of Biscay, Gipuzkoa and Álava, just as others of the Nation.

Navarre had hoped its 1841 Ley Paccionada (Compromise Act) would protect it. But they soon found out the Spanish government also had plans for Navarre.

From 1876 onwards, Basques had to join the Spanish military individually, not in their own groups. This was hard for many Basques who barely spoke Spanish, leading to very stressful experiences.

Basque Economic Agreement

When Basque self-government ended, there were still issues to solve, like tax collection and military service. The Basque Liberal leaders in the cities wanted to keep home rule. During the military occupation, which lasted until 1878, freedom of speech was limited, especially for those who supported the fueros. To get their message out, Basque political figures started a newspaper called La Paz in Madrid. It included new and old supporters of home rule from all four Basque areas.

The Spanish prime minister wanted to get rid of all traces of home rule. But Canovas was practical. Besides military bases, customs officials, and courts in the cities, the Spanish government had almost no presence in the Basque Provinces. They also knew very little about the Basque region.

Navarre seemed unaffected by the problems in Álava, Biscay, and Gipuzkoa. But in early 1877, Canovas del Castillo decided to also get rid of Navarre's 'Compromise Act'. He said it was just a regular law. He also wanted to change Navarre's tax payments, which had been the same since 1841, to make them like a regular Spanish province.

During the debates, the big difference between the government and the Basques-Navarrese became clear. Canovas insisted that the 1839 and 1841 laws were not treaties. He said, "A matter of force comes to constitute Law, since force is Law when force generates a status," trying to explain his view. The government's law passed in the Spanish parliament with 123 votes for and 11 against (four Navarrese and seven other Basques). This led to an unstable situation. The government then sent a lawyer, Count Tejada de Valdosera, to Navarre to reach a new agreement. This led to the "Tejada-Valdosera Convention," which guaranteed Navarre's special administrative setup within Spain.

In the Basque Provinces, the first call for Basques to join the Spanish military in November 1877 was strongly opposed by the general councils. Tensions rose again. Canovas demanded the order be carried out immediately. The Spanish government then appointed new provincial councils, who had to answer to the Spanish governmental official in each area. In Biscay, which was most against the abolition of the fueros, Canovas ordered the immediate shutdown of their general councils. Álava and Gipuzkoa followed.

However, the tense situation convinced the Spanish prime minister that a compromise with the three Basque councils was the only way to prevent more trouble and ensure long-term stability. Negotiations between Canovas's government and Liberal officials from the three Basque Provinces led to the 1st Basque Economic Agreement on February 28, 1878. It was meant to be a temporary solution for 8 years. This agreement was based on the Tejada-Valdosera Convention for Navarre. The official announcement of the agreement highlighted its supposed benefits: 1. Extending the Spanish constitution to all Spain. 2. Including the Basque Provinces in the military draft. 3. Making them contribute to the Spanish treasury like everyone else.

The new provincial councils were now in charge of collecting taxes in their area. Then, they would negotiate how much money they would give to the central government. With this agreement, the Spanish government hoped to reduce regional feelings and create a strong base for industrial growth and a stronger central government.

What Happened Next

Basque businesses now had the protection of state tariffs, meaning they benefited from a Spanish market where they faced less competition. The Spanish government initially planned the Basque Economic Agreement to be temporary. But it was very successful for industrial growth, investment, and income. The main beneficiaries, the government and local city businesses, quickly wanted to renew the Economic Agreement for another 8 years, and then again. The initial unity among Basques to defend the fueros from 1876 to 1878 faded once the worst of the political crisis was over.

Thanks to the new economic and administrative system, Biscay grew incredibly fast. Greater Bilbao became a major center of economic development in Europe. The different interests among Basques soon became clear. This weakened the pro-fueros movement and helped the wealthy industrialists become part of Spain. In Navarre, the movement to fully restore the fueros lasted a bit longer, led by lawyer Arturo Campion. But their political goals were later taken over by the rising electoral Carlism from 1886. A group of people concerned about the loss of self-government and the fast decline of Basque identity in Navarre founded the Asociación Euskara of Navarre. They focused on cultural events rather than politics.

Unlike the coastal areas, Álava and Navarre slowly became less wealthy. They remained farming areas with peasants, small farmers, and landowners. Navarre stopped being the most populated area, and Álava also shrank. Population growth shifted to Biscay and Gipuzkoa. People continued to emigrate to the Americas, a trend that started decades earlier. About 200,000 people out of 800,000 left during the 19th century.

The demand for cheap labor in mining and industry brought thousands of immigrants, first from nearby Basque areas and then from other parts of Spain. This was the first time so many people moved to the Basque Country. This led to the creation of trade unions from 1879, especially Socialists, who aimed to protect workers' rights. The newcomers had little reason to feel connected to their new home or their Basque employers. The new Socialist movement embraced Spanish nationalism to unite the working class. They wanted to remove Basque-specific features, believing they were "against the mass struggle."

The Tejada-Valdosera Convention didn't solve everything for Navarre. The approval of the law led to new tax demands on Navarre by the Spanish treasury. The minister Gabriel Gamazo tried to make Navarre completely like a regular Spanish province. This led to a popular uprising called the Gamazada (1893-1894). This event also led to the founding of modern Basque nationalism by Sabino Arana, mainly in Biscay.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de los fueros vascongados y navarros en el siglo XIX para niños

In Spanish: Historia de los fueros vascongados y navarros en el siglo XIX para niños

|

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |