African Civilization Society facts for kids

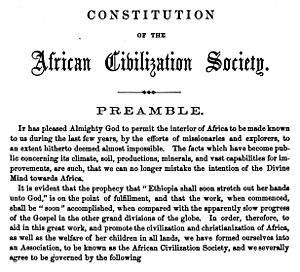

Preamble to the constitution

|

|

| Formation | 1858 |

|---|---|

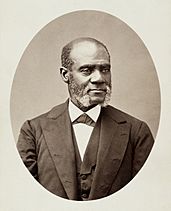

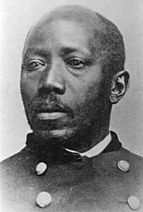

| Founders | Henry Highland Garnet Martin Delany |

| Dissolved | 1869 |

| Type | Black-led organization |

| Purpose | Education and self-determination for the African diaspora |

| Headquarters | New York City |

|

Main organ

|

Freedmen's Torchlight People's Journal |

The African Civilization Society (ACS) was an organization led by Black Americans. It was founded in New York City in 1858 by Henry Highland Garnet and Martin Delany. The ACS aimed to help people of African descent, known as the African diaspora.

The group started because of important events in the 1850s. These events made Black Americans feel unsafe. One key event was the 1857 Dred Scott v. Sandford Supreme Court decision. This ruling said that Black Americans had no rights as citizens.

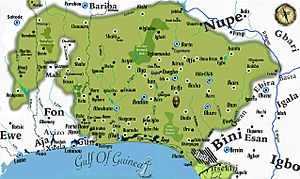

At first, the ACS wanted to create a colony in Yorubaland, West Africa. They hoped this colony would help Black Americans achieve self-determination. They also wanted to spread Western ideas in Africa and fight the Atlantic slave trade. Their goal was to grow cotton and molasses using free labor. This would compete with products made by enslaved people in the US and Caribbean.

However, most Black Americans did not want to move to Africa. After the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, the ACS changed its focus. It became the only Black-led group to educate formerly enslaved people, called freedmen, in the Southern United States.

By the 1860s, the ACS was very active. They supported Freedmen's Schools with 8,000 students. They also employed 129 teachers. The organization stopped its work in 1869 after 11 years.

Contents

Why the Society Started

The American Colonization Society was formed in 1816. Its goal was to help enslaved and free Black Americans move to Liberia in West Africa. Liberia was a colony founded in 1821. Many people in the American Colonization Society believed Black people did not belong in the US.

Most Black Americans did not support this idea of moving to Africa. But some leaders, like Martin Delany and Henry Highland Garnet, started to rethink it. This was due to several events in the 1850s.

- The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 made free Black Americans unsafe. They could be kidnapped and forced into slavery.

- The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 allowed slavery to spread into new US territories. This went against earlier agreements.

- The Dred Scott v. Sandford Supreme Court decision in 1857 was very alarming. It said Black Americans had no constitutional rights.

These events made Garnet and Delany believe Black Americans needed a new plan. Garnet thought that growing cotton and molasses in Africa with free labor could weaken slavery in the Americas. Delany wrote a book in 1852. He argued that Black Americans had no future in the US. He concluded that moving away was the best option.

Early Years: Colonization (1858–1863)

Garnet and Delany, with other Black New Yorkers, started the African Civilization Society (ACS) in September 1858. They imagined Black Americans moving from the US to Yorubaland in West Africa. There, they would share Christianity and Western ways of life with Indigenous Africans.

The ACS especially wanted to stop the Atlantic slave trade. They also aimed to weaken the slave economies in the US and Caribbean. They planned to do this by training Africans to produce cotton and molasses. These products would then compete in global markets with goods made by enslaved people.

The society also promoted self-determination for all people of African descent. Their constitution stated their goal was to help "civilization and evangelization of Africa, and the descendents of the African ancestors." In 1859, Delany explored the Niger River in West Africa for possible colony sites. This trip led to a separate project called the Niger Valley Exploring Party.

In 1860, ACS director Theodore Bourne went to England. He wanted to get support and money for the Yorubaland colony. An affiliate group called the African Aid Society was formed there. Delany was also in England promoting his own project. This caused some confusion among British audiences.

Later that year, Elymas P. Rogers led ACS members to West Africa. He went to find colony locations. Sadly, he died of malaria soon after arriving in Liberia. In April 1861, the ACS held a meeting to raise $10,000. This money was for 20 Black Americans, led by Garnet, to emigrate to Yorubaland.

In August 1861, Garnet traveled to England to build interest. In November, ACS supporters met with Delany. He suggested that the ACS should be controlled by "colored people of America." He said their "white friends" could be "aiders and assistants." The society agreed to this. They affirmed that the group's goal was "Self-Reliance and Self-Government on the Principle of an African Nationality." This meant the African race would be the main ruling group.

In 1864, the ACS moved its headquarters to Weeksville, Brooklyn. This was a free Black community. It had been set up years earlier as an alternative to moving to Liberia.

Some national Black leaders, like Frederick Douglass, were wary of the ACS. They worried because the ACS seemed similar to the white-led American Colonization Society. Douglass said in 1863 that the ACS's plan was "the fruits of the same vine as colonizationists." He added, "The African Civilization Society says to us, go to Africa.... To which we simply reply, 'we prefer to remain in America;'".

Later Years: Education (1863–1869)

The American Civil War changed everything. Especially after the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, many ACS supporters focused on the war. They wanted to help the Union Army end slavery in the US. Garnet joined the army as a chaplain. Delany became a Major in a Colored Troops unit.

Under the new ACS president, George W. LeVere, the group shifted its focus. They stopped planning for emigration. Instead, they focused on educating formerly enslaved people, called freedmen. In 1863, they expanded their mission. They decided to help and educate newly freed people in the American South, Central America, South America, the British West Indies, and Africa.

The new constitution, adopted in 1864, aimed to end the slave trade. It also sought to uplift and Christianize Africa and all people of African descent. Their programs reflected Black nationalist ideas. They helped Black Americans educate themselves. They also encouraged them to lead their own education programs. They wanted Black people to create their own political and social groups. Between 1863 and 1867, the ACS was the only Black-led group opening Freedmen's Schools in the South.

During the war, Black activist Junius C. Morel said the ACS was "fully in the field." They were "holding meetings, collecting clothes, books, paper" for freedmen. They were also "making arrangements to send colored teachers." By 1866, the ACS employed 69 teachers. They taught 2,000 students in the Northeastern United States.

By 1868, they had 129 teachers. They supported schools in Virginia, Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Washington, D.C. These schools had a total of 8,000 students. The annual cost was $53,700. Among their teachers were Maria W. Stewart and Hezekiah Hunter.

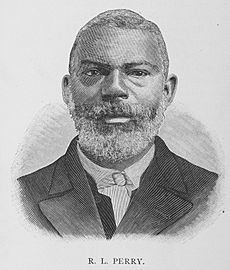

The ACS also published a monthly newspaper, the Freedmen's Torchlight. It focused on the "temporal and spiritual interests of the Freedmen." Many important Black intellectuals from Brooklyn wrote for it. These included editor Rev. Rufus L. Perry, Henry M. Wilson, Junius C. Morel, and Martin Delany. The organization also had a weekly newspaper called People's Journal.

Most ACS supporters lived in Manhattan, Brooklyn, and Philadelphia. But smaller groups formed in Ohio, Connecticut, Ontario, and Washington, D.C. Leaders like Richard H. Cain and J. Sella Martin joined the group. However, the ACS began to struggle financially in 1866. It officially closed down in 1869.

See also

- Niger expedition of 1841

- Committee for the Relief of the Black Poor

- Nova Scotian Settlers

- Back-to-Africa movement

- Free African Society

- African Americans in Africa

- Haitian emigration

- Colonization societies

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |