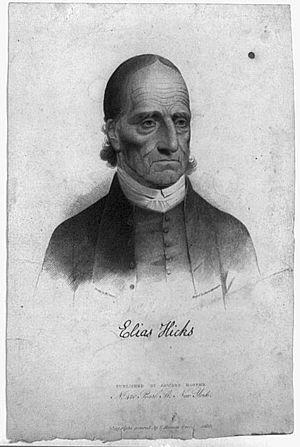

Elias Hicks facts for kids

Elias Hicks (born March 19, 1748 – died February 27, 1830) was an important Quaker minister from Long Island, New York. He traveled a lot to share his ideas. His teachings caused a big disagreement, which led to a major split within the Quaker community. Elias Hicks was also the older cousin of the famous painter Edward Hicks.

Early Life

Elias Hicks was born in Hempstead, New York, in 1748. His parents, John and Martha Hicks, were farmers. Elias first worked as a carpenter. In his early twenties, he became a Quaker, just like his father.

On January 2, 1771, Elias married Jemima Seaman, who was also a Quaker. They got married at the Westbury Meeting House. They had eleven children, but only five lived to be adults. Elias later became a farmer. He settled on his wife's family farm in Jericho, New York. This place is now known as the Elias Hicks House. He and his wife often offered free places to stay for travelers on the Jericho Turnpike. This way, travelers did not have to stay in taverns.

In 1778, Hicks helped build the Friends meeting house in Jericho. This building is still used for Quaker worship today. Hicks was a very active preacher in Quaker meetings. By 1778, he was recognized as a recorded minister. People thought he was a great speaker. He had a strong voice and a dramatic way of speaking. Thousands of people would come to hear him preach. Even the young writer Walt Whitman heard Hicks speak in Brooklyn in 1829.

Fighting Against Slavery

Elias Hicks was one of the first Quaker abolitionists. Abolitionists were people who wanted to end slavery. In 1778, he joined other Quakers on Long Island who were already freeing their slaves. The Quakers at Westbury Meeting were among the first in New York to do this. By 1799, all Quaker slaves in Westbury were freed.

In 1794, Hicks helped start the Charity Society of Jericho and Westbury Meetings. This group helped poor African Americans in the area. They also made sure that their children could get an education.

In 1811, Hicks wrote a book called Observations on the Slavery of Africans and Their Descendents. In this book, he said that slavery was wrong. He also connected it to the Quaker idea of peace. He believed slavery was a result of war. He also pointed out that people supported slavery for money. They bought goods made by enslaved people.

Hicks suggested that people should stop buying goods made by slaves. This would remove the reason for slavery to exist. He wrote: "What effect would it have on the slave holders and their slaves, should the people of the United States of America and the inhabitants of Great Britain, refuse to purchase or make use of any goods that are the produce of Slavery? It would doubtless have a particular effect on the slave holders, by circumscribing their avarice, and preventing their heaping up riches, and living in a state of luxury and excess on the gain of oppression…"

His book gave a strong argument for the free produce movement. This movement encouraged people to only buy goods made by free workers. These goods included cotton cloth and cane sugar. Many stores that sold free produce were started by Quakers. The first one was opened by Benjamin Lundy in Baltimore in 1826.

Hicks also supported Lundy's plan to help freed slaves move to Haiti. In 1824, he held a meeting at his home in Jericho to discuss this. Later, in the 1820s, he suggested raising money to buy slaves their freedom. He wanted them to settle as free people in the American Southwest.

Hicks played a part in ending slavery in his home state of New York. New York passed laws like the 1799 Gradual Abolition Act. Then came the 1817 Gradual Manumission in New York State Act. These laws led to the final freedom of all remaining slaves in New York on July 4, 1827.

His Beliefs

Elias Hicks believed that listening to the "Inner Light" was the most important thing. The Inner Light is the idea that God's guidance is within each person. He thought this was the main rule of faith and the core of Christianity.

Some people accused him of not believing in Jesus's divinity. But Hicks had different views. He believed Jesus showed perfect obedience to the Inner Light. He often called Jesus our "great pattern." Hicks encouraged others to grow in love and goodness, just as Jesus did.

Hicks also did not believe in ideas like original sin or an outside Devil. He thought that wrongdoing came from human "passions" or "propensities." He believed these natural urges were given by God. But problems happened when people used these urges too much, without God's guidance.

He was worried that many Quakers were following old traditions too much. He felt they were not truly experiencing God's power. He also thought many other Christians were just following rules and forms. Hicks believed true worship came from quietness and listening to the law in one's heart. He said that if ministers only read from notes, they would be "dumb." He felt that many religious beliefs were just based on tradition, not on real experience.

Hicks also talked about the Bible. He said that the Bible could give good lessons. But only if people read it with the help of God's spirit. He believed that without the Inner Light, people could misunderstand the Bible. He even said that people who only relied on the Bible might "kill one another for the Scriptures' sake."

He also believed that outward worship, like making images, could become "idolatry." He stressed that true worship was an inner connection with God.

Elias Hicks worked hard to guide Quakers toward what he saw as a true connection with God. He believed that traditions, books, and even the Bible could sometimes get in the way of that inner light. Even at 81, facing many challenges, he never changed his mind. He believed the Inner Light was the only way to find true peace and love from God.

The Quaker Split

The split among Quakers was not just because of Hicks's teachings. It was also partly due to the Second Great Awakening. This was a time when many Protestant churches saw a revival of faith.

However, Hicks's ideas did cause tension among Quakers as early as 1808. As he became more influential, some English Quaker leaders visited New York. They spoke out against his views between 1821 and 1827. These visits made the differences among American Quakers even worse.

One influential person was Anna Braithwaite. She visited the United States from 1823 to 1827. In 1824, she wrote a book that described Hicks as a radical. Hicks felt he had to respond. He published a letter in return. But neither side changed their minds.

In 1819, Hicks focused on influencing Quaker meetings in Philadelphia. This led to years of arguments. Things came to a head in 1826.

After the 1826 Philadelphia Yearly Meeting, where Hicks spoke about the Inner Light being more important than the Bible, Quaker elders decided to check the beliefs of all ministers. This caused a lot of anger. It all came to a head at the next Philadelphia Yearly Meeting in 1827. Hicks was not there. The meeting could not agree on a new clerk, which led to a big division.

At first, the split was meant to be temporary. But by 1828, there were two separate Quaker groups in Philadelphia. Both claimed to be the real Philadelphia Yearly Meeting. Other yearly meetings in places like New York, Baltimore, Ohio, and Indiana also split. Those who followed Hicks were called Hicksites. His critics were called Orthodox Friends. Each group believed they were truly following the original Quaker ideas.

The split also had to do with social and economic differences. Hicksite Friends were often poorer and lived in rural areas. Orthodox Friends were usually from cities and were middle-class. Many rural Hicksite Friends kept to older Quaker traditions, like "plain speech" and "plain dress." Quakers in towns and cities had often stopped these practices.

Both the Orthodox and Hicksite Friends later had more splits. The main Orthodox group followed the ideas of English Quaker Joseph John Gurney. His ideas were more like traditional Protestant churches. Some Orthodox Friends disagreed with Gurney's ideas. They formed other groups like the Wilburite and Conservative meetings. Some Hicksite Friends also disagreed with changes in their group. They formed Congregational or Progressive groups.

In 1828, the split also reached the Quaker community in Canada. These Quakers had moved there from New York and Pennsylvania in the 1790s. This led to two separate Yearly Meetings in Canada, just like in the United States.

The division between Hicksites and Orthodox Friends in the U.S. was very deep and lasted a long time. It took many decades for them to come back together. The first reunified meetings happened in the 1920s. The Baltimore Yearly Meeting finally reunited in 1968.

Later Life

On June 24, 1829, when he was 81 years old, Elias Hicks went on his last trip to preach in western and central New York State. He returned home to Jericho on November 11, 1829. In January 1830, he had a stroke that partly paralyzed him. On February 14, 1830, he had another stroke that made him unable to move. He died about two weeks later, on February 27, 1830. His last wish was that no cotton blanket, which was made by enslaved people, should cover him on his deathbed. Elias Hicks was buried in the Jericho Friends' Burial Ground. His wife, Jemima, had died earlier, on March 17, 1829.

See also

In Spanish: Elias Hicks para niños

| Ernest Everett Just |

| Mary Jackson |

| Emmett Chappelle |

| Marie Maynard Daly |