Amawalk Friends Meeting House facts for kids

Quick facts for kids |

|

|

Amawalk Friends Meeting House

|

|

South and east elevations, 2013

|

|

| Location | Yorktown Heights, New York |

|---|---|

| Nearest city | Peekskill |

| Area | 2.9 acres (1.2 ha) |

| Built | 1831 |

| NRHP reference No. | 89002004 |

| Added to NRHP | November 16, 1989 |

The Amawalk Friends Meeting House is a historic building in Yorktown Heights, New York. It was built in the 1830s using a special wood frame style called timber frame. In 1989, this building and its nearby cemetery became a recognized historic place on the National Register of Historic Places.

The Quakers, also known as Friends, have been active in this part of Westchester County since the mid-1700s. The current meeting house is the third one they built, as the first two were destroyed by fire. It's special because it's one of the best-preserved Quaker meeting houses in the area. It's also rare because it was built by a group of Quakers called "Hicksites" during a time when Quakers were divided.

The building looks a bit like the Greek Revival style, which is unusual for Quaker buildings. Later, a porch was added, giving it some Victorian touches. Even though the inside was updated when meetings started again, many of its original items are still there.

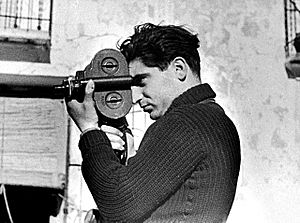

Most of the property is a cemetery where many early Quaker members are buried. Interestingly, the famous war photographer Robert Capa and his brother Cornell are also buried here, even though they weren't Quakers. Their gravestones show the simple Quaker burial style. A newer building, the First Day School, was added in the 1970s. It looks similar to the meeting house but is not considered historic because it's newer.

Exploring the Meeting House and Grounds

The Amawalk Friends Meeting House, its First Day School, and the cemetery are on a 2.9-acre (1.2 ha) piece of land. This land is on the west side of Quaker Church Road. This road also marks the border between the towns of Yorktown and Somers. The property is about half a kilometer north of where Quaker Church Road meets Saw Mill River Road. This area used to be a small village called Amawalk. The name is still used for the meeting house and the Amawalk Reservoir, which is part of the New York City water supply system.

The land here has small hills and low areas, often with creeks or wet spots. The meeting house property slopes up towards the west. It drains into a small stream that flows into the Muscoot River. The neighborhood around it is mostly homes on large, wooded lots.

Across Quaker Church Road are two houses. Behind them is a path for power lines and the North County Trailway, a popular walking and biking path. To the west of the meeting house is Amawalk Hill Cemetery, and another cemetery, Carpenter Hill, is to the north.

The Meeting House Building

A short gravel driveway leads to the property. Old oak and maple trees shade the area. The meeting house is a two-and-a-half-story building made of wood. It measures about 9 meters by 12 meters. The main part of the building has wooden shingles on its sides. A small section of flat wooden boards, called clapboard, is just below the roof. The building sits on a stone foundation. A single brick chimney goes through the middle of the slate-shingled roof.

A porch with a slanted roof runs along the front (south) side of the first floor. On the west side, there's a small, one-story addition with a slanted roof and clapboard siding.

There are two separate entrances on the ground floor, under the porch. They have double wooden doors. The windows are typical six-over-six double-hung windows with wooden frames and wooden shutters. The east side of the building has similar windows. The western addition and the back (north) side have similar windows, but without shutters.

The porch has a low concrete floor. In the middle, there are three simple wooden benches arranged in a square. At the west end of the porch, a wooden door leads into the small addition. The porch roof is held up by seven square wooden pillars with curved decorations at the top.

On the second story, all windows are two-over-two double-hung windows without shutters. A smaller two-over-two window is in the top part of both the front and back gables, at the attic level. On the front, decorative brackets support a molded edge, similar to the porch.

Inside the Meeting House

Both entrances open into the main meeting room. This room has cushioned wooden benches, like those on the porch, facing the center. Some benches, meant for the meeting's leaders (called elders), are fixed in place on three raised steps. Other benches can be moved around. Two small folding tables are at the ends of the elders' bench, used for taking notes. In the middle of the room are two small wood-burning stoves, one of which is from the late 1800s. The building does not have modern heating, plumbing, or electricity.

The floor of the room is covered in linoleum. On the plain plaster walls, you can still see where a wall used to divide the room into separate sections for men and women. A door frame from that old wall is also visible on the south side. A door in the west wall leads to the addition, which is used as a cloakroom and a simple outdoor toilet (privy). Inside, you can see the building's original hand-cut wooden beams.

Several wooden pillars, some with old kerosene lamps, support a wooden balcony, called a gallery. Stairs in the southern corners lead up to it. The gallery is about 2.5 meters above the ground floor. It's about 2.7 meters deep on the south side and 2.1 meters deep on the east and west sides. The south part of the gallery has loose benches, while the other sections have fixed ones. A ladder on the east side goes up to the full-length attic. In the attic, just like in the cloakroom, you can see the building's wooden support beams.

First Day School and Cemetery

On the south side of the parking lot is the First Day School building. It's a smaller wooden building with a pointed roof, similar in style and color to the meeting house. It was built in the 1970s where the meeting's stable used to be. Because it's newer, it's not considered a historic part of the property.

The cemetery, which goes up the hillside to the west, is considered a historic part of the property. Its graves, some of which are covered in plants, date from the late 1700s to today. The oldest grave with a clear name is that of Eugent Weeks, who died in 1805. Early gravestones are made of sandstone, while later ones are marble.

Many of the gravestones show the Quaker value of simplicity. They don't have much art, except for some on the southwest corner that have a weeping willow design. They simply list the person's name, their relationship to others nearby, and their birth and death dates. Some graves don't have any markers at all.

A Look at History

The Religious Society of Friends, or Quakers, started in the mid-1600s and faced challenges in England. They were seen as different because they didn't have a strict church hierarchy or clergy. Many Quakers moved to the American colonies to find more freedom. Their numbers grew, but they didn't feel completely safe holding open meetings until the mid-1700s.

Early Days of Amawalk Meeting (1760–1797)

As Quakers gained more acceptance, new meetings started. Northern Westchester County was a busy area for this growth. The Amawalk meeting likely began around 1760. In 1772, the Amawalk meeting was allowed to build its first meeting house on the current site. It was finished the next year.

In 1779, the first meeting house was damaged by fire. Repairs were made, but the meeting decided to build a new one. The second meeting house was finished in 1785. It was described as being similar in size to the building we see today.

While the new house was being built, the Amawalk Quakers met in Chappaqua. The meeting also started to get involved in the community. In 1791, they opened a school, but it closed two years later because they couldn't find enough teachers. Instead, they decided to support a boarding school being planned by another Quaker meeting in Dutchess County.

The Amawalk meeting also worked for social change. By 1784, they reported that none of their members owned slaves, showing their strong stance against slavery.

Growth and a Quaker Split (1798–1839)

In 1798, Amawalk became its own Monthly Meeting, which meant it could make more of its own decisions. More members joined. By 1828, Amawalk oversaw several smaller Quaker meetings.

That same year, a big split happened among American Quakers. Some Quakers, called "Orthodox," started to adopt practices similar to other Christian churches, like hymns and prayers. Others, led by Elias Hicks, believed in the "inner light" as the main way to connect with God. The Amawalk Quakers chose to follow Hicks. The Orthodox members left and built their own meeting house nearby in 1832, but it's no longer standing.

Near the end of 1830, the Amawalk meeting house burned down completely. The very next year, in 1831, the current meeting house was built. Its construction cost a bit more than the planned $1,250.

This meeting house is special for two reasons. First, it's rare to find a meeting house built by a Hicksite group, as they usually stayed in older buildings. Second, its design shows some influence from the popular Greek Revival style of the time. This is unusual for Quaker buildings, which usually prefer a very simple look. Originally, the inside of the meeting house had a wall to separate men's and women's business meetings, which is why there are two entrances.

By the mid-1830s, 74 families were members of the meeting. People came and went, but new members joined. The Quakers continued their activism. For example, in 1839, one member was jailed for 16 days because he refused to pay a "military demand" of $5.

Challenges and Changes (1840–1903)

Membership started to drop in the 1840s, partly because of the Quaker split and other changes in society. Around this time, the small shed addition was built on the west side of the meeting house. Some people believe the building was a stop on the Underground Railroad, a secret network that helped slaves escape to freedom, but this has never been proven.

The American Civil War (1861-1865) tested the beliefs of all Quakers, including those at Amawalk. Quakers are known for their opposition to war. After the war, the meeting's decline continued. To try and help, the Society of Friends stopped discouraging members from holding public office in 1869. The Amawalk meeting also added two wood-burning stoves in 1883 to heat the building in colder weather. The porch, added in the 1800s, also shows some Victorian style, which was unusual for Quaker meeting houses.

Even though members remained active in social issues, like supporting prohibition (banning alcohol) and asking the state to replace the death penalty with life imprisonment, these efforts weren't enough to stop the decline in members. By 1886, Amawalk had only 96 members. In 1897, Amawalk became an executive meeting, and in 1903, it became an official organization.

Famous Burials and Closure (1904–1976)

Meetings continued, though not regularly, despite the ongoing drop in members. In 1920, Hicksite and Orthodox Quakers began to work towards reuniting.

In 1930, the carpet inside the meeting house was replaced with linoleum. The Amawalk meeting stayed active, focusing on supportive activities. They collected books for libraries serving African-American communities and knitted blankets during World War II. After the war, they sponsored two young women from Hiroshima, Japan, who came to the United States for medical treatment after the atomic bomb.

In 1954, the famous war photographer Robert Capa died in Vietnam while covering a war. He was known for his powerful photos from World War II. Even though Capa was not a Quaker, his editor, John Morris, felt a Quaker funeral would be a good way to honor him. Morris believed Capa's photos, showing the horrors of war, helped promote peace. So, a Quaker service was held at Amawalk.

The few remaining Amawalk members allowed Capa to be buried in their cemetery. Later, his mother and sister-in-law were buried in the same plot. In 2008, his brother Cornell, who founded the International Center for Photography, was also laid to rest there. None of them were Quakers.

By 1964, the meeting no longer had enough members to continue, and it officially closed. The building was left empty and started to show signs of neglect.

Revival and Renovation (1977–Present)

Four years after Amawalk closed, the Hicksite and Orthodox Quakers fully reunited in 1968. This, along with a renewed interest in spiritual matters, helped bring new life to the Society of Friends. Meetings started again at Amawalk in 1977. Soon after, a window was added to the south side of the cloakroom, which is the most recent change to the building's outside.

The new members made fixing up the property a top priority. The First Day School building was finished in 1987. It was built on the site of an old horse stable and had modern facilities. During the week, a local nursery school used it. That same year, Amawalk had enough members to become a monthly meeting again.

In 1993, four years after the property was listed on the National Register of Historic Places, the meeting received a $50,000 grant from the state to help renovate the inside of the building. The interior had been damaged by insects and water over the years. The meeting raised its half of the money through an auction of historic photos organized by Cornell Capa.

See also

- List of Quaker meeting houses

- National Register of Historic Places listings in northern Westchester County, New York

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |