Michael Shiner facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Michael G. Shiner

|

|

|---|---|

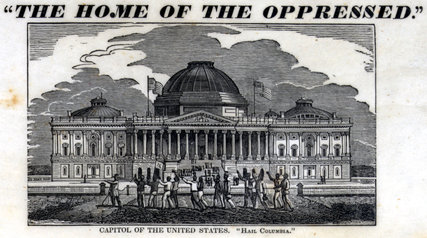

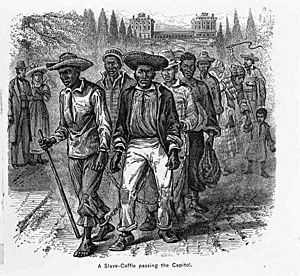

A coffle of enslaved men in front of the US Capitol in the 1830s

|

|

| Born | 1805 |

| Died | January 16, 1880 (aged 74–75) |

| Known for | Diary records of Washington D.C. for more than 60 years |

Michael G. Shiner (1805–1880) was an African-American worker at the Washington Navy Yard. He was also a diarist who wrote about events in Washington D.C. for over 60 years. He started writing as a slave and continued after he became a free man.

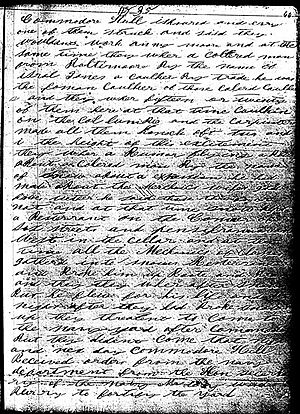

His diary is the oldest known by an African American living in Washington, D.C. It gives historians a firsthand look at many important events. These include the War of 1812, the British attack on Washington, and the burning of the U.S. Capitol and Navy Yard. Shiner also wrote about his family's rescue from slavery. His diary shares details about working conditions at the shipyard, the 1835 Washington Navy Yard labor strike, the Snow Riot, and other events of the 1800s.

Contents

Michael Shiner's Early Life and Education

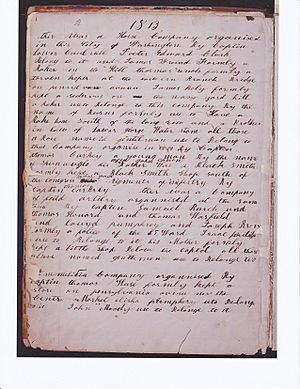

Michael Shiner was born into slavery in 1805. He grew up on a farm in Piscataway, Maryland. The farm belonged to William Pumphrey Jr., his slaveholder. Around 1813, Pumphrey brought young Shiner to Washington, D.C., to work as a "servant."

Shiner started writing in his "book" (he never called it a diary) in 1813. He wrote about major public events he saw or read about. He also included some important personal moments. He wrote using phonetic spelling and not much punctuation.

It's not fully known how Shiner learned to read and write. Laws at the time often stopped black people from learning outside of religious classes. Some historians think he learned at a small school at the Navy Yard. This school was run by white abolitionists. A report from 1870 confirms Shiner learned to read as an adult. It mentions a Sunday school at the First Presbyterian Church of Washington. This school taught many black people to read the Bible. Michael Shiner was one of them.

Witnessing the War of 1812

Shiner remembered watching the British invasion of Washington DC during the War of 1812. He wrote, "They looked like flames of fire, all red coats... and the iron work shined like a Spanish dollar."

In 1878, he recalled the British burning buildings near the Capitol. He said he was an "eye witness to all this." He watched as the British army burned homes and stayed in Washington for two days.

During the war, some enslaved people escaped to join the British forces. Rear Admiral Sir Alexander Cochrane had promised freedom to those who joined them. One man, Archibald Clark, escaped from James Pumphrey, who also held Shiner's future wife, Phillis. News of Clark's escape might have reached young Michael Shiner.

Family Life and Marriage

In his early twenties, Shiner went to a Sunday school. It was run by the First Presbyterian Church of Washington. This school was for both free and enslaved black people. He also attended Ebenezer Methodist church services.

Around 1828, Shiner married Phillis, a 20-year-old woman. She had been bought by James Pumphrey, William Pumphrey's brother. Michael and Phillis lived near the Navy Yard and had six children. The Shiner family often attended the Ebenezer Methodist Church. Many black and white shipyard workers also attended this church.

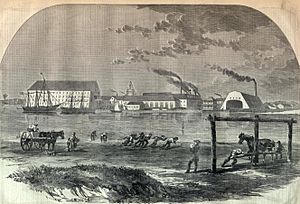

From 1800 to 1830, the Washington Navy Yard was the biggest employer of enslaved African Americans in the District. In 1808, enslaved workers made up one-third of the workforce. Their numbers slowly went down over the next 30 years.

William Pumphrey, like many slaveholders, rented his enslaved workers to the Navy Yard. Shiner was listed as an "Ordinary Seaman" in the Navy Yard records starting July 1, 1826.

The "Ordinary" was where naval ships were kept in reserve. Enslaved African Americans worked there as seamen, cooks, or laborers. They did many difficult jobs like scraping ship hulls and moving timber. Their wages were paid directly to their owners. Enslaved workers received limited medical care. This was mainly to protect the slaveholders' property. Shiner was treated for "fever" twice.

The names of enslaved men like Michael Shiner were often put on military lists as "ordinary seamen." This was a way to avoid official oversight. Shiner himself wrote, "We belonge to the ordinary at that time..." This was a common trick used by slaveholders.

Working Conditions and Weather

Shiner's diary describes daily life at the Navy Yard. He shares important details about working conditions. He wrote about being surrounded by a group of people who lit firecrackers around him. Another time, he had to run from sailors who thought he was a runaway slave. He also nearly drowned after falling into freezing water.

Shiner also wrote about unusual weather. He recorded the extreme cold and crop failures during the Year Without a Summer in 1816. He noted, "ther Wher a frost every night the hold summer the Where no corn Made." Weather was important because most workers, enslaved and free, worked outdoors. He also wrote about a meteor shower in 1833. He said, "It frightened the people half to death."

Labor Strike and Snow Riot

Shiner also wrote about the 1835 Washington Navy Yard labor strike. This strike turned into the Snow Riot, a race riot by white people against black people. President Andrew Jackson and the U.S. Marines eventually stopped it.

In July 1835, Shiner wrote that white mechanics threatened black workers. They forced black caulkers (people who sealed ship seams) to quit working on the USS Columbia. He added that striking white mechanics attacked a free black restaurant owner named Beverley Snow. They also threatened to attack Commodore Isaac Hull.

Abraham Lincoln

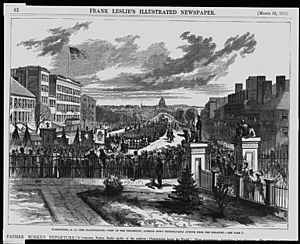

Shiner loved public events in Washington, D.C. He attended almost all presidential inaugurations. He saw presidents from John Quincy Adams to Abraham Lincoln's second inauguration.

At Lincoln's second inauguration in 1865, Shiner noted the large crowd and unusual weather. He wrote that when Lincoln came out to speak, the wind and rain stopped. The sun came out, and a bright star appeared over the Capitol.

After learning of Lincoln's assassination, Shiner wrote about the sad event. He noted that Lincoln and his wife had visited the Navy Yard just before he was killed.

From Slavery to Freedom

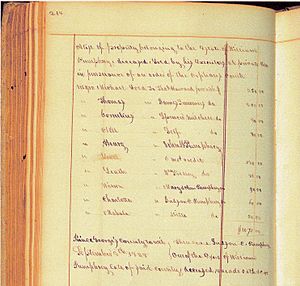

When William Pumphrey died in 1827, his will said his eight slaves would be sold as "term slaves." This meant they would be freed after a certain time. Michael Shiner was to be freed after 15 more years of enslavement.

Shiner was then bought by Thomas Howard, a Navy Yard clerk, in 1828. Howard's will said Shiner would be freed in 1836 if he behaved well.

In 1833, James Pumphrey, William's brother, died. Shiner wrote that his wife Phillis and their three children were "snacht away from me and sold." They were taken by slave dealers and held in a slave pen in Alexandria. Phillis and her children were being sold to pay off debts.

Luckily, Phillis got help from a famous lawyer, Francis Scott Key. He filed a petition for their freedom. With help from Key and other powerful people, Phillis and her children were declared free.

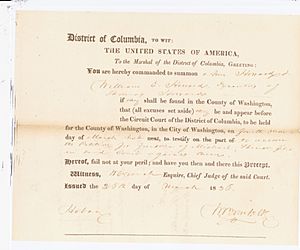

When Shiner felt that Thomas Howard's family was not going to free him as promised, he fought for his own freedom. In 1836, he filed a petition in court. He said he was being held "unjustly, and illegally."

By 1840, Michael Shiner and his family were listed as "free colored" in the census. As a free man, he continued to work at the Navy Yard as a painter. He saved money and supported his family. He worked there until after 1870.

Family and Property

Shiner's first wife, Phillis, died before 1849. In 1850, Michael Shiner was living with his second wife, Jane Jackson, and their children.

Even as a free man with a job and property, Shiner and his family faced challenges. They were subject to Black Codes, which were laws that limited the rights of black people. They also faced prejudice. Free black people had to carry freedom papers. Without them, they could be arrested. To protect their children, black parents sometimes made them apprentices. Shiner did this with a relative of his second wife.

In 1861, a newspaper wrongly reported that "Mike Shiner and his wife (colored) had been arrested on suspicion" of a crime. The newspaper later corrected itself. It said, "Mike Shiner is a very respectable colored man, an employee in the Navy Yard."

After the Civil War, Shiner became more successful. He was active in the Republican Party and spoke out for black rights. In 1870, the census showed his property was worth a lot of money. His daughter, Mary Ann Shiner Almarolia, was also well-known. She managed a hotel and saloon and became a midwife.

Community Involvement and Politics

Shiner was very involved in local politics in Washington, D.C. He strongly supported the Republican Party. In 1871, he won a contract to gravel a street and lay sidewalks.

Later, when the city's governor was accused of corruption, Shiner was called to testify. He firmly denied any wrongdoing by himself or the governor. He stated he was a "laboring man in the paint shop of the Washington Navy Yard." He said he won the contract fairly.

After slavery ended, Shiner and his son Isaac were active in public life. They marched in President Ulysses S. Grant's inauguration parade in 1869. Shiner also attended the yearly celebration of the District of Columbia Compensated Emancipation Act.

However, Shiner became unhappy with the Republican Party. He felt they were not doing enough to protect the rights of newly freed black people. He spoke at meetings, saying that black men should support any party that was honest with them. He famously said, "Michael Shiner has never sold out and never will be found to sell out."

Michael Shiner's Death and Legacy

Michael G. Shiner died from smallpox on January 17, 1880. He was buried the next day in a segregated cemetery. The Evening Star newspaper published an obituary. It called him "a well known colored man" with an amazing memory.

After his death, Shiner's diary went to his wife and then his daughter, Mary Ann. In 1904, after Mary Ann died, the diary was found in a locked box. One part of the diary was sold and eventually ended up at the Library of Congress.

The Library of Congress has had the diary since at least 1906. It was microfilmed in the 1930s. In 1941, parts of the diary were read on a radio show. The show called it "A breathless tale... written in bad, but lyrical English." In 2002, the diary was part of a Library of Congress exhibit called An African-American Odyssey.

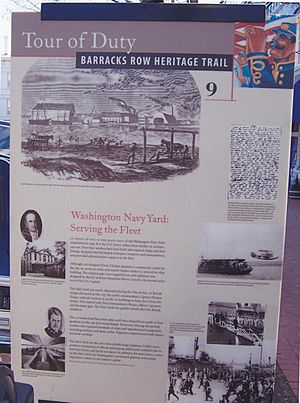

In 2004, Washington, D.C., created a "Heritage Trail." Michael Shiner's life is honored on marker number 9, near the Navy Yard. His former home site is also recognized.

In 2007, Shiner's "book" was fully written out and published by the Naval History and Heritage Command. It is called The Diary of Michael Shiner Relating to the History of the Washington Navy Yard 1813-1869. Michael Shiner's life and diary have become very popular. Books for young readers, like Tonya Bolden's Capital Days Michael Shiner's Journal, have been written about him. Historian William G. Thomas III called Shiner's diary "perhaps the most remarkable on-the-ground perspective there is from an enslaved person in Washington D.C."

| Calvin Brent |

| Walter T. Bailey |

| Martha Cassell Thompson |

| Alberta Jeannette Cassell |