Civil rights movement (1865–1896) facts for kids

The civil rights movement (1865–1896) was a time when African Americans worked hard to gain equal rights and opportunities after slavery ended in the United States. This period, right after the American Civil War, saw big changes for black communities in the South.

The U.S. government started a program called Reconstruction to rebuild the Southern states. This program also helped former slaves become citizens and join society. During this time, black people gained political power and many were able to buy land. However, some white people were angry about these changes. They started groups like the Ku Klux Klan and later paramilitary groups such as the Red Shirts and White League. These groups used violence to stop black people from gaining rights.

In 1896, the Supreme Court made a ruling in a case called Plessy v. Ferguson. This ruling said that "separate but equal" facilities for different races were legal. This was a big setback for civil rights. It meant that black people could be kept separate from white people in public places, as long as the separate places were supposedly equal. From 1890 to 1908, Southern states also passed new laws that made it very hard for most black people to vote. This situation lasted for many years, even into the 1960s.

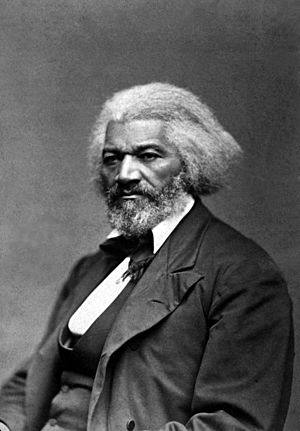

Many early efforts for civil rights were led by the Radical Republicans, a group within the Republican Party. Later, a group called the lily-white movement tried to reduce the power of black people in the party. Important civil rights leaders during this time included Frederick Douglass (1818–1895) and Booker T. Washington (1856–1915).

Contents

Reconstruction Era (1863-1877)

Reconstruction lasted from 1863, when President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, until 1877.

After the Civil War, President Lincoln faced big questions. What would happen to the former slaves, called "Freedmen"? How would the Southern states rejoin the country? What rights would former rebels have? And who would make these important decisions, the President or Congress?

Many Freedmen faced starvation and had no homes or jobs. The government created the Freedmen's Bureau to help them. This was the first major federal agency to provide relief.

Three important changes to the U.S. Constitution, called the "Reconstruction Amendments," were passed to expand rights for black Americans:

- The Thirteenth Amendment made slavery illegal everywhere.

- The Fourteenth Amendment said that all people born in the U.S. were citizens and guaranteed them equal rights.

- The Fifteenth Amendment said that a person's race could not stop them from voting.

Congress also passed laws like the Enforcement Acts (1870–71) and the Civil Rights Act of 1875. These laws allowed the federal government to make sure that civil rights were protected, even if state governments ignored the problem.

For a few years, former Confederate leaders still controlled most Southern states. But after the 1866 elections, the Radical Republicans gained power in Congress. President Andrew Johnson wanted to be easy on the former rebels, but Congress was much stricter. They gave black men the right to vote and temporarily stopped many former Confederate leaders from holding office. New Republican governments formed in the South. These governments were made up of Freedmen, "Carpetbaggers" (people who moved from the North), and "Scalawags" (white Southerners who supported the Republicans). The U.S. Army supported these new governments.

Opponents said these governments were corrupt and violated the rights of white people. Slowly, these Republican governments lost power to a group of conservative Democrats. By 1877, this group controlled the entire South, often using violence and dishonest methods.

In response to these changes, the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) appeared in 1867. This white-supremacist group was against black civil rights and Republican rule. President Ulysses Grant used the Ku Klux Klan Act of 1870 to stop the Klan, and it broke up. However, violence to stop black people from voting continued in many Southern states after 1868.

By 1874, other paramilitary groups like the White League and Red Shirts openly used threats and violence. Their goal was to stop black people from voting and weaken the Republican Party. They wanted white political power to return to the South.

Reconstruction ended after the disputed 1876 United States presidential election. As part of a deal, Rutherford B. Hayes became president, and the federal government removed its troops from the South. This left the Freedmen to the control of white conservative Democrats, who then regained power in state governments.

Migration to Kansas

After Reconstruction ended, many black people were afraid of groups like the Ku Klux Klan and the White League. They also worried about Jim Crow laws, which made them second-class citizens. Inspired by leaders like Benjamin "Pap" Singleton, about forty thousand "Exodusters" left the South. They moved to Kansas, Oklahoma, and Colorado. This was the first large movement of black people after the Civil War.

In the 1880s, black people bought more than 20,000 acres (81 km²) of land in Kansas. Some of the towns they founded, like Nicodemus, Kansas (started in 1877), still exist today. Many black people left the South believing they would get free travel to Kansas, but some got stuck in St. Louis, Missouri. Black churches in St. Louis and people from the East who wanted to help formed groups like the Colored Relief Board. These groups helped those stranded in St. Louis reach Kansas.

One specific group was the Kansas Fever Exodus. Six thousand black people moved from Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas to Kansas. Many in Louisiana decided to leave when the state ruled that voting rights were a state matter, not a federal one. This opened the door for Louisiana to take away voting rights from its black population.

Not all African Americans supported this move. Frederick Douglass, for example, thought it was not well-planned.

Political Organization

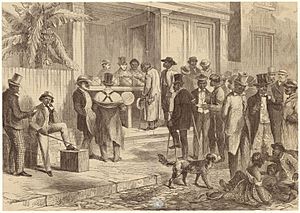

In 1867, black men across the South gained the right to vote and joined the Republican Party. They often organized through the Union League, a secret group supported by the national Republican Party. By the end of 1867, almost every black voter in the South had joined the Union League or a similar group. Meetings were usually held in black churches or schools.

The Union Leagues also helped black people form groups to protect themselves from harassment. Members were not allowed to vote for the Democratic Party. After 1869, the KKK violently attacked the Union Leagues, and they mostly fell apart.

Black ministers were often important political leaders, along with black people who had been free in the North before the Civil War. Many cities had black newspapers that explained issues and brought the community together.

Political Divisions

In the South, the Republican Party often split into two groups. One group, called the "Black-and-tan faction," included black people and their white allies from the North (carpetbaggers). The other group, the "lily-white faction," was made up of white Southern Republicans (scalawags). These names became common after 1888.

Black people made up most of the Republican voters, but they received only a small share of political jobs and favors. They demanded more power. Black workers started to take control of local party groups. They chose black candidates for office and even nominated all-black slates for elections.

The "black-and-tan" group usually won these internal party fights. However, as white Republicans lost these battles, many started voting for conservative or Democratic candidates. The Republican Party became more and more focused on black voters as it lost white support. This division weakened the Republican Party in the South.

Populist Movement

In 1894, many farmers in the South were unhappy. In North Carolina, poor white farmers from the Populist Party teamed up with the Republican Party, which was mostly black in the low country and poor white in the mountains. This group gained control of the state legislature in 1894 and 1896, and the governor's office in 1896.

The state legislature lowered property requirements for voting, which helped both white and black voters. In 1895, they gave jobs to their black allies, appointing 300 black judges and many deputy sheriffs and police officers.

White Democrats were determined to get back power. They started a campaign based on white supremacy and fears about mixed-race relationships. Their "white supremacy" campaign in 1898 was successful, and Democrats regained control of the state legislature.

However, in Wilmington, the largest city with a black majority, a biracial government had been elected. Democrats had planned to overthrow this government if they lost, and they did so in the Wilmington insurrection of 1898. Democrats forced black and biracial officials out of town. White mobs attacked the only black newspaper and then black areas of the city, killing and injuring many people. They also destroyed homes and businesses. About 2,100 black people left the city for good, making it a white-majority city. This event showed that such biracial coalitions would not last in the South. In 1899, the white Democratic legislature in North Carolina passed a law that took away voting rights from most black people. They would not get these rights back until the federal Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Economic and Social Life

Most black people during this time were farmers. There were four main groups:

- Tenant farmers, sharecroppers, and agricultural laborers worked for white landowners.

- The fourth group owned their own farms, which gave them some independence from white economic control.

City Life

The South had few large cities in 1860. But during and after the war, many people, both black and white, moved from farms to cities. The growing black population created a group of leaders, including ministers, professionals, and business owners. These leaders often made civil rights a top priority. Most black people in cities worked in unskilled or low-skilled jobs.

Historian August Meier noted that from the late 1880s, black-owned businesses grew rapidly. These included banks, insurance companies, funeral homes, and stores. These businesses served the black community and promoted racial self-help and unity.

Memphis

During the Civil War, thousands of enslaved people escaped to Union Army lines. A camp for them was set up near Memphis, Tennessee. By 1865, the black population in Memphis had grown from 3,000 to 20,000. White Irish Catholics in the city, who competed with black people for jobs, resented the presence of black Union soldiers.

In 1866, a major riot broke out, with white people attacking black people. Forty-five black people were killed, and many more were injured. Much of their housing was destroyed. By 1870, the black population was 15,000 out of a city total of 40,226.

Robert Reed Church (1839–1912), a freedman, became the South's first black millionaire. He made his money by buying and selling city land, especially after yellow fever epidemics caused many people to leave Memphis. He started the city's first black-owned bank, Solvent Savings Bank, which helped black businesses get loans. He was very involved in politics and helped direct support to the black community. His son also became an important politician in Memphis. Robert Reed Church was a leader in black society and supported many causes. Because the city's population dropped, black people found new opportunities. They were hired as police officers until 1895, when segregation forced them out.

Atlanta

Atlanta, Georgia was destroyed during the war. But as a major railroad center, it quickly rebuilt and attracted many people from rural areas. From 1860 to 1870, Fulton County (where Atlanta is) more than doubled in population. Many freedmen moved from plantations to towns or cities to find work and live in their own communities. Fulton County went from 20.5% black in 1860 to 45.7% black in 1870.

Atlanta quickly became a leading center for black education. Teachers and students there supported discussions and actions for civil rights. Atlanta University was founded in 1865. The school that became Morehouse College opened in 1867, and Clark University opened in 1869. What is now Spelman College opened in 1881, and Morris Brown College in 1885. These schools helped create one of the nation's oldest and most established African American elite groups in Atlanta.

Philadelphia

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania was one of the largest cities in the North. Many free black people moved there before the Civil War. By the 1890s, some neighborhoods had a bad reputation for crime, poverty, and death rates. W. E. B. Du Bois, in his important study The Philadelphia Negro (1899), used facts to challenge these stereotypes. His work showed how segregation negatively affected black lives and reputations. Du Bois realized that racial integration was important for equality in American cities.

Education for Black Americans

The African-American community worked hard for good public schools for a long time. Historian Hilary Green says this was "not just a fight for reading and writing, but one for freedom, citizenship, and a new social order after the war." Black communities and their white supporters in the North believed that education was key to achieving equal civil rights.

Before the Civil War, many Southern states had laws against teaching black people, both free and enslaved, to read and write. Because of this widespread illiteracy, creating new schools for black children was a top priority. This included both private schools and public schools funded by state taxes. During Reconstruction, states passed laws for this, but putting them into practice was difficult in most rural areas. After Reconstruction, state funding for black schools was very limited, but local black communities and national religious groups helped.

Black leaders generally supported separate, all-black schools. They wanted black principals and teachers, or white teachers who were strongly supportive and sponsored by Northern churches. Public schools were segregated throughout the South during Reconstruction and for many decades after. New Orleans was one of the few places where schools were sometimes integrated during Reconstruction.

During Reconstruction, the Freedmen's Bureau opened 1,000 schools across the South for black children using federal money. Many students eagerly enrolled. By the end of 1865, over 90,000 Freedmen were attending public schools. The schools taught subjects similar to those in the North. However, after Reconstruction, state funding for black schools was very low, and their facilities were poor.

Many Freedmen's Bureau teachers were well-educated women from the North, motivated by their religious beliefs and opposition to slavery. About half the teachers were Southern whites, one-third were black, and one-sixth were Northern whites. Black men were slightly more numerous than black women among the teachers. Only the black teachers showed a strong commitment to racial equality, and they were the most likely to continue teaching.

High School and College Education

Almost all colleges in the South were strictly segregated. Only a few Northern colleges accepted black students. Private schools were started across the South by churches, especially Northern ones, to provide education beyond elementary school. These schools focused on high school level work and offered some college courses. Tuition was low, so national and local churches often provided financial support for the colleges and helped pay teachers. The largest organization dedicated to this was the American Missionary Association.

By 1900, Northern churches or groups they supported ran 247 schools for black people in the South. They had a budget of about $1 million, employed 1,600 teachers, and taught 46,000 students. At the college level, the most famous private schools were Fisk University in Nashville, Atlanta University, and Hampton Institute in Virginia. A few were founded in Northern states. Howard University was a federal school in Washington, D.C.

In 1890, Congress expanded a program to include federal support for state-sponsored colleges in the South. This meant that Southern states with segregated systems had to create black colleges so that all students had a chance to go to college. Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute was important because it set standards for industrial education. Even more influential was Tuskegee Normal School for Colored Teachers, founded in 1881 by Alabama and led by Booker T. Washington until his death in 1915.

In 1900, few black students were enrolled in college-level programs. Only 22 black people graduated from college before the Civil War. Oberlin College in Ohio was a pioneer, graduating its first black student in 1844. The number of black graduates grew quickly: 44 in the 1860s, 313 in the 1870s, 738 in the 1880s, 1,126 in the 1890s, and 1,613 from 1900–1909. These graduates became professionals: 54% became teachers, 20% became ministers, and others were doctors, lawyers, or editors. Many of them supported civil rights activities in their communities.

Funding for Education

Money for black education in the South came from several places. From 1860 to 1910, religious groups and charities gave about $55 million. Black people themselves, through their churches, contributed over $22 million. Southern states spent about $170 million in tax money on black schools, but about six times that amount on white schools.

Wealthy Northerners gave a lot of money to educate black people in the South. The largest early funding came from the Peabody Education Fund. George Peabody, a rich businessman, gave $3.5 million to support education for "destitute children of the Southern States."

The John F. Slater Fund for the Education of Freedmen was created in 1882 with $1.5 million to help the "legally emancipated population of the Southern states." After 1900, even larger amounts came from John D. Rockefeller's General Education Board, Andrew Carnegie, and the Rosenwald Foundation.

By 1900, the black population in the U.S. was 8.8 million, mostly in the rural South. About half of the 3 million school-aged black children were attending school. They were taught by 28,600 teachers, most of whom were black. Schools for both white and black children focused on basic reading, writing, and arithmetic for younger kids. There were only 86 high schools for black students in the entire South, plus 6 in the North. These 92 schools had 161 male teachers and 111 female teachers, teaching 5,200 high school students. In 1900, only 646 black students graduated from high school.

Religion and Community

Black churches played a very strong role in the civil rights movement. They were the main community groups where black Republicans organized their political activities. After 1865, most black Baptist and Methodist churches quickly became independent from the mostly white national or regional church groups. Black Baptist congregations formed their own associations. Their ministers became important political spokesmen for their communities. Black women also found their own roles and church-sponsored groups, from choirs to missionary projects, and church schools.

In San Francisco, there were three black churches in the early 1860s. They all worked to represent the interests of the black community. They provided spiritual guidance, helped those in need, and fought against laws that denied black people their civil rights. These San Francisco churches had strong support from the local Republican Party. In the 1850s, the Democratic Party controlled the state and passed anti-black laws. Even though slavery never existed in California, these laws were harsh. When the Republican Party gained power in the early 1860s, they opposed these racist laws. Republican leaders joined black activists to win legal rights, especially the right to vote, to attend public schools, to be treated equally in public transportation, and to have equal access to the court system.

After being freed from slavery, black Americans actively formed their own churches, mostly Baptist or Methodist. They gave their ministers important moral and political leadership roles. Almost all black people left white churches, so few integrated churches remained (except for some Catholic churches in Louisiana). Four main organizations competed to form new Methodist churches for freedmen in the South:

- The African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME), founded in Philadelphia.

- The African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church (AMEZ), founded in New York City.

- The Colored Methodist Episcopal Church (CME), supported by the white Southern Methodist Church.

- The well-funded Methodist Episcopal Church (Northern white Methodists).

By 1871, the Northern Methodists had 88,000 black members in the South and had opened many schools for them.

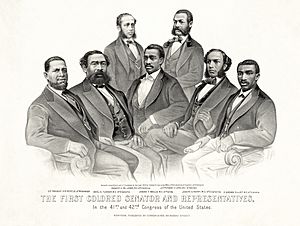

During the Reconstruction Era, black people were the main supporters of the Republican Party, and ministers played a powerful political role. Ministers could speak out more freely because they did not depend on white support, unlike teachers, politicians, business owners, and tenant farmers. Following the idea that a minister must also look out for the political interests of his people, over 100 black ministers were elected to state legislatures during Reconstruction. Several served in Congress, and one, Hiram Rhodes Revels, served in the U.S. Senate.

Methodist Churches

The African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME) was the most organized and active black church. In Georgia, AME Bishop Henry McNeal Turner (1834–1915) became a leading voice for justice and equality. He was a pastor, writer, newspaper editor, politician, Army chaplain, and a key leader of the growing black Methodist organization in Georgia. During the Civil War in 1863, Turner became the first black chaplain in the United States Colored Troops. Afterward, he worked for the Freedmen's Bureau in Georgia. He settled in Macon, Georgia, and was elected to the state legislature in 1868 during Reconstruction. He started many AME churches in Georgia. In 1880, he was elected as the first Southern bishop of the AME Church. He fought against Jim Crow laws.

Turner was a leader of black nationalism and encouraged black people to move to Africa. He believed in the separation of races. He started a "back-to-Africa" movement to support the black American colony in Liberia. Turner built black pride by saying "God is a Negro."

There was another all-black Methodist Church, the smaller African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church (AMEZ). AMEZ remained smaller than AME partly because some of its ministers could not perform marriages, and many avoided political roles. Its finances were weak, and its leadership was generally not as strong as AME. However, it was a leader among Protestant churches in allowing women to become ministers and giving them powerful roles. One important leader was Bishop James Walker Hood (1831–1918) of North Carolina. He not only built his network of AMEZ churches but also was the grand master for the entire South of the Prince Hall Masonic Lodge, a non-religious group that strengthened political and economic power within the black community.

Many black Methodists were also part of the Northern Methodist Church. Others were associated with the Colored Methodist Episcopal Church (CME), which was linked to the white Southern Methodist Church. Generally, the most politically active black ministers were part of the AME.

Baptist Churches

Black Baptists separated from white churches and formed independent groups across the South. They quickly created state and regional associations. Unlike the Methodists, who had a system led by bishops, Baptist churches were mostly independent of each other. However, they shared resources for missionary work, especially missions in Africa. Baptist women worked hard to create their own roles within the church.

City Churches

Most black people lived in rural areas where church services were held in small, simple buildings. In cities, black churches were more noticeable. Besides regular religious services, city churches had many other activities, such as prayer meetings, missionary societies, women's clubs, youth groups, public lectures, and music concerts. They also held revivals that lasted for weeks and attracted large, enthusiastic crowds.

Churches did a lot of charity work, caring for the sick and needy. Larger churches had organized education programs, in addition to Sunday schools and Bible study groups. They held literacy classes to help older members read the Bible. Private black colleges, like Fisk in Nashville, often started in church basements. Churches also supported small black businesses.

Most importantly, churches played a political role. They hosted protest meetings, rallies, and Republican party conventions. Important church members and ministers made political deals and often ran for office until black people lost their voting rights in the 1890s. In the 1880s, the ban on alcohol was a major political issue that allowed black churches to work with white Protestant groups who felt the same way. In every case, the pastor was the main decision-maker. Their salary ranged from $400 to over $1,500 a year, plus housing. This was a lot of money at a time when 50 cents a day was good pay for unskilled labor.

Methodist churches increasingly sought ministers who had graduated from college or seminary. However, most Baptists felt that too much education might reduce the strong religious feeling and speaking skills they wanted in their ministers.

After 1910, as black people moved to major cities in both the North and South, a pattern emerged of a few very large churches with thousands of members and paid staff, led by influential preachers. At the same time, there were many smaller "storefront" churches with only a few dozen members.

Deteriorating Status

After 1880, legal conditions for black people got worse, and they had almost no power to fight back. In 1890, Northern allies in the Republican Party tried to pass laws in Congress to stop these worsening conditions, but they failed. Every Southern state passed laws requiring segregation in most public places. These laws, known as Jim Crow laws, lasted until 1964.

From 1890 to 1905, Southern states systematically reduced the number of black people allowed to vote to about 2%. They did this through rules that avoided directly mentioning race, so they seemed to follow the 15th Amendment. These rules included requiring people to pay a poll tax, pass literacy tests, and other unfair methods. In 1896, the U.S. Supreme Court supported Jim Crow in the case of Plessy v. Ferguson, saying that "separate but equal" facilities for black people were legal under the 14th Amendment.

Jim Crow Laws and Segregation

In 1866, many "Black Codes" in the Southern states made marriage between black and white people illegal. The new Republican governments in six states ended these laws. But after Democrats regained power, the ban was put back in place. It wasn't until 1967 that the U.S. Supreme Court, in Loving v. Virginia, ruled that all such laws in 16 states were unconstitutional.

In the 1860s, it was a big question how to define who was black and who was white, especially since many white men had children with black enslaved women. Often, a person's reputation as black or white was most important. However, most laws used a "one drop of blood" rule, meaning that having just one black ancestor legally made a person "black." At first, legal segregation was only in schools and marriage. But this changed in the 1880s when new Jim Crow laws forced the physical separation of races in public places.

From 1890 to 1908, Southern states effectively took away voting rights from most black voters and many poor white voters. They did this by making voter registration harder with poll taxes, literacy tests, and other unfair rules. They also passed segregation laws, creating a system known as Jim Crow that treated black people as second-class citizens. This system lasted until the civil rights movement of the mid-20th century.

Efforts for equality often focused on transportation, like segregation on streetcars and railroads. Starting in the 1850s, lawsuits were filed against segregated transportation in both the North and South. Some famous people who challenged these rules included Elizabeth Jennings Graham in New York, Charlotte L. Brown and Mary Ellen Pleasant in San Francisco, Ida B. Wells in Memphis, and Robert Fox in Louisville.

Violence and Intimidation

During this period, groups like the Ku Klux Klan, White League, and Red Shirts used violence and threats to scare black people and stop them from voting or holding office. This was a major challenge to civil rights.

Public Images of Black People

In the newspapers and other media of the late 1800s, black people were often shown in very negative ways. They were stereotyped as criminals, savages, or funny figures. They were often shown as superstitious, lazy, violent, or immoral. Booker T. Washington, a young college president from Alabama, became famous for speaking out against these very negative stereotypes. He showed that black people were making progress and were loyal, patriotic Americans who deserved a fair chance.

Important Leaders

Much of the black political leadership during this time came from ministers and black veterans of the Civil War. White political leaders were often veterans and lawyers. It was hard for ambitious young black men to become lawyers, with a few exceptions like James T. Rapier, Aaron Alpeoria Bradley, and John Mercer Langston.

The upper class among the black population was often of mixed race and had been free before the war. During Reconstruction, 19 of the 22 black members of Congress were of mixed race. These wealthier, mixed-race black people made up most of the leaders in the civil rights movement of the 20th century as well. However, many leaders were also dark-skinned and had been enslaved.

Anna J. Cooper

In 1892, Anna J. Cooper (1858–1964) published a book called A Voice from the South: By A Woman from the South. After this, she gave many speeches calling for civil rights and women's rights. Her book was one of the first to discuss Black feminism. It promoted the idea that black women could achieve self-reliance and improve their lives through education and social uplift. Her main idea was that if black women made progress in education, morals, and spirituality, the entire African-American community would improve. She believed that educated black women would bring more elegance to education. Cooper argued that educated and successful black women had a duty to help other black women who were less fortunate. Her essays also covered topics like racism, the economic situations of black families, and the Episcopal Church.

Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (1818–1895) was an escaped slave who became a tireless activist against slavery before the war. After the war, he was an author, publisher, speaker, and diplomat. His biographer said that Douglass "made a career of agitating the American conscience." He spoke and wrote about many reform causes, including women's rights, temperance, peace, and free public education. But he spent most of his time and energy working to end slavery and gain equal rights for African Americans. These were the most important goals of his long career. Douglass believed that the fight for freedom and equality needed strong, constant, and determined action. He also knew that African Americans had to play a big role in that fight. Less than a month before he died, when a young black man asked for his advice, Douglass replied: "Agitate! Agitate! Agitate!"

Other Key Figures

- Norris Wright Cuney (1846–1898), a union organizer from Galveston, Texas and chairman of the Republican Party of Texas.

- Timothy Thomas Fortune (1856–1928), a journalist, publisher, and founder of the National Afro-American League.

- John Mercer Langston (1829–1897), a lawyer from Virginia, U.S. House representative, and president of Virginia Normal and Collegiate Institute (now Virginia State University).

- Isaac Myers (1835–1891), a trade union leader and founder of the Colored National Labor Union.

- Robert Smalls (1839–1915), a Civil War hero, U.S. House representative from South Carolina, and founder of the Republican Party of South Carolina.

- Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin (1842–1924), an editor, organizer, suffragist, and founder of the Woman's Era, the first newspaper by and for African-American women.

- Sojourner Truth (1797–1883), a famous speaker and activist.

- Booker T. Washington (1856–1915), an educator, author, and the first head of the Tuskegee Institute.

- Ida B. Wells (1862–1931), a journalist, newspaper editor, and activist.

Timeline of Key Events

- 1863 - Emancipation Proclamation frees most enslaved people.

- 1863 - Daniel Payne becomes the first black college president, at Wilberforce University in Ohio.

- 1865 - Congress creates the Freedmen's Bureau.

- 1865 - The Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution officially ends slavery.

- 1865 - Shaw Institute is founded in Raleigh, North Carolina, the first historically black college (HBCU) in the South.

- 1865 - Southern states pass "Black Codes" to limit the rights of Freedmen, but the Freedmen's Bureau blocks these laws.

- 1865 – Atlanta University is founded.

- 1866 - Civil Rights Act of 1866 is passed, making all people born in the U.S. citizens.

- 1866 - The first chapter of the Ku Klux Klan is formed in Pulaski, Tennessee.

- 1866 - The U.S. Army forms the Buffalo Soldiers (African American regiments).

- 1866 - Lincoln Institute (later Lincoln University) is founded by black Union soldiers.

- 1867 - Howard University is founded in Washington, D.C., with federal funding.

- 1868 - The Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution guarantees citizenship and equal protection under the law.

- 1870 - The Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution protects voting rights regardless of race.

- 1870 - Hiram Rhodes Revels becomes the first black U.S. Senator; Joseph Rainey becomes the first black U.S. House Representative.

- 1870 - African American Police Constable Wyatt Outlaw is killed by the Ku Klux Klan in Graham, North Carolina.

- 1871 - The US Civil Rights Act of 1871, also known as the Klan Act, is passed.

- 1872 - P.B.S. Pinchback becomes the first black Governor of a U.S. state.

- 1873 - In the Slaughterhouse Cases, the Supreme Court limits the reach of the 14th Amendment.

- 1873 - The Colfax and Coushatta Massacres occur, with murders of black and white Republicans in Louisiana.

- 1874 - Paramilitary groups like the White League and Red Shirts are founded. They use violence to suppress black voting and disrupt the Republican Party.

- 1875 - Civil Rights Act of 1875 becomes law.

- 1876 - The Hamburg Massacre occurs, where white people riot against African Americans celebrating the Fourth of July.

- 1877 - With the Compromise of 1877, federal troops leave the South, ending Reconstruction.

- 1879 - The Exodus of 1879 sees thousands of African Americans move to Kansas.

- 1880 - In Strauder v. West Virginia, the Supreme Court rules that black people cannot be excluded from juries.

- 1880s - Segregation of public transportation begins in Southern states.

- 1881 - Booker T. Washington opens the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute (HBCU) in Tuskegee, Alabama.

- 1883 - The Supreme Court rules the Civil Rights Act of 1875 unconstitutional, saying the 14th Amendment applies to states, not individuals.

- 1885 - A biracial populist group briefly gains power in Virginia.

- 1885 - African-American Samuel David Ferguson is ordained a bishop of the Episcopal church.

- 1886 - Norris Wright Cuney becomes chairman of the Republican Party of Texas, the most powerful role held by any African American in the South during the 19th century.

- 1890 - Mississippi passes a new constitution that effectively takes away voting rights from most black people through poll taxes, residency, and literacy tests.

- 1892 - Ida B. Wells publishes her pamphlet Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases.

- 1893 - Ida B. Wells, Frederick Douglass, and others protest black exclusion from the Chicago World's Fair.

- 1895 - Booker T. Washington gives his Atlanta Compromise speech at the Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta, Georgia.

- 1895 - W. E. B. Du Bois is the first African American to earn a Ph.D. from Harvard University.

- 1896 - Norris Wright Cuney loses his position as chairman of the Texas Republican Party.

- 1896 - In Plessy v. Ferguson, the Supreme Court upholds racial segregation with the "separate but equal" rule.

|

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |